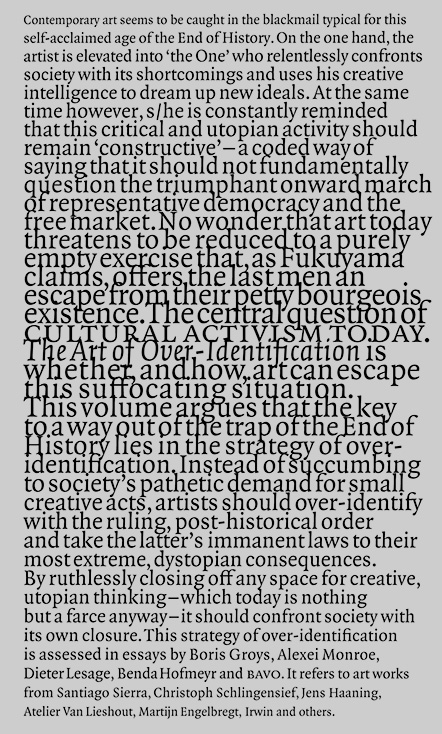

Cultural Activism Today.

The Art of Over-Identification

January 1, 2007review,

BAVO (eds.), Cultural Activism Today. The Art of Over-Identification, Episode Publishers, Rotterdam, 2007, isbn 978905973068, 128 pages

Cultural Activism Today. The Art of Over-Identification is a book edited by the research team bavo and with contributions by bavo, Alexei Monroe, Brenda Hofmeyr, Dieter Lesage and Boris Groys.1 It touches upon questions of the activist potentials of over-identification as an alternative to critical and utopian artistic strategies. The editors regard over-identification as ‘a certain tendency in contemporary art, in which artists, faced with a world that is more than ever ruled by a calculating cynicism, strategically give up their will to resist, capitulate to the status quo and apply the latter’s rules even more consistently and scrupulously than the rest of society’ (p. 6). Thus, by manifestly aligning their art with market interests or neoliberal logics, artists-activists can cause, according to bavo, the public’s outrage about things that the latter disapprove of, but would otherwise not bother reacting against.2

Exploring new approaches to art as resistance is an extremely timely and complex task. Additionally, the selection of authors makes this volume a worthwhile pick among an overwhelming production of literature on contemporary critical art practices. However, here I will focus almost exclusively on bavo’s own texts, in which they theorize and advocate over-identification as artistic activism strategy. Because unlike in the analyses by the other authors, in Bavo’s texts one is faced with some striking presumptions and sweeping generalizations. Consequently, the editors-authors’ initial credible endeavours run the risk of being subverted by their own argumentation. Slightly perverse, as this is what over-identification is supposed to do...

To be more precise, there are some noticeable presumptions about art and its functions. The considering of over-identification as a more effective strategy compared to other strategies of artistic resistance seems to take for granted that art can effectively and recognizably reach activist goals, provided the correct strategy is found. This appears to further imply that, firstly, engaged artists should prioritize effectiveness – though the content of ultimate outcomes is nowhere specified. Secondly, that there exist criteria of measuring and judging art’s activist effectiveness or efficiency.

The texts contain certain presumptions about the subjects behind the strategies. Actually, while the departure point of bavo’s consideration of over-identification lies with outcomes – effectiveness of the strategy – of certain ways of cultural activism over others, they constantly discuss over-identification at the level of conscious intentions. However, in the examples they provide, they conspicuously bypass the question whether activism is part of, for instance, Santiago Sierra’s intention, or art part of the Yes Men’s intention. As a strategy, over-identification cannot be accidental but deliberate activism. As Brenda Hofmeyr also accentuates, intention is prominent: ‘Over-identification as such is intrinsically invested with political purport. It cannot be dissociated from a certain deliberate and determined activism...’ (p. 77). Which is why Hofmeyr concludes with scepticism about Atelier van Lieshout’s over-identification strategies as activism: ‘Behind their creative flirtations with capitalism, communism and anarchism, there is no clear position recoverable, no unambiguous desire, just a certain lingering immaturity’ (p. 78).

From another point of view, by accepting over-identification as a conscious strategy, at least some artists-activists will hardly be able to escape schizophrenia. Because even if an activist-artist adopts his ‘opponent’s’ point of view and strategically over-identifies with a position in order to subvert it from within, how can he then build up a character and career out of this practice?3 Unless, after performing a position as a role, masks are ripped off, revealing the artist to be a good guy. But that would no longer be over-identification as position-taking, but performance as role-playing. Actually, bavo’s example of activist theatre-maker Christopher Schlingensief matches this perfectly. It remains unclear where and how theatre practices, which by their nature are characterized as role-playing, are transformed into over-identification.

bavo makes use of sweeping generalizations. For instance, ‘free market’ or ‘capitalism’ are placed next to ‘representative democracy’ as equivalent and mutually feeding evils of our times! (pp. 7, 27) Is representative democracy really so bad? And if so, ideologically speaking, as a political system, or in the ways it is applied?

bavo are quite critical of ‘ngo art’, using as exemplary case the artist Jeanne van Heeswijk, known for projects in neighbourhoods considered problematic to Dutch society’s standards (pp. 23–27). But what exactly is understood as ‘ngo art’ here? Historically, the 1990s growth of Non Governmental Organisations came in the aftermath of political and social rights movements in the developing world from the 1960s onwards, and the promotion by the United Nations of a normative framework for internationally accepted human and civil rights.4 ngo art refers formally to artistic interventions as part of human or development aid in areas suffering deprivations or human rights violations such as in Latin America’s slums or in the Middle East. What do these have to do with the largely stated-funded (even if indirectly) Dutch institutional apparatus supporting art in neighbourhoods, apart from some artists’ good social intentions? Is this not simply sweeping away an abundance of aesthetic, social and other differentiations disrespectfully onto a heap, treating different artistic interventions and sociopolitical situations as equivalent, whether they are interventions in Rotterdam neighbourhoods or art in Cairo?

As a consequence of such inaccuracies, simplifications and of inattention to detail and differentiation between juxtaposed examples, bavo’s argumentation, for all its good intentions, runs the risk of operating counterproductively in the reader’s response. Even for a reader in search of cultural resistance strategies to adapt and models to identify with. To paraphrase Alexei Monroe explaining how the subversion of nationalist symbols works in Neue Slowenishe Kunst, one could claim that with their argumentation bavo might eventually ‘in the process alienate’ activist strategies of over-identification ‘from those who normally wield them’ (p. 56).

1. bavo is comprised of the architect-philosophers Gideon Boie and Matthias Pauwels. The book is the outcome of the symposium Cultural Activism Now. Strategies of Over-Identification organised by bavo with the support of the Jan van Eyck Academy at the Stedelijk Museum CS, Amsterdam, January 2006. For further activities and publications see www.bavo.biz.

2. A known example from the Netherlands is the project Regoned (short for Registratie Orgaan Nederland) by artist Martijn Engelbregt. The artist distributed pseudo-governmental inquiries in Amsterdam, asking people to report information on illegal residents they were aware of. The project caused outrage. Several people did not at first recognize the action as art. It stirred memories of informing against Jewish people during the Second World War, as well as confronting people with the fact that virtually everyone in Amsterdam knows people who rent illegally.

3. This point about the necessity to first identify with a position in order to even strategically over-identify with it and the question of an individual’s capacity and willingness to constantly present oneself in a reverse – to its ‘true’ – ideological position , was already raised by artist Jonas Staal during the book launch at Witte de With, Rotterdam, 3 November 2007.

4. For ngos see, for instance, Middle East Report, no. 214: Critiquing ngos. Assessing the Last Decade (spring 2004).

Eva Fotiadi is Lecturer in Contemporary Art and Theory at the University of Amsterdam and the Gerrit Rietveld Academy of Arts. In 2011, her book The Game of Participation in Art and the Public Sphere was published.