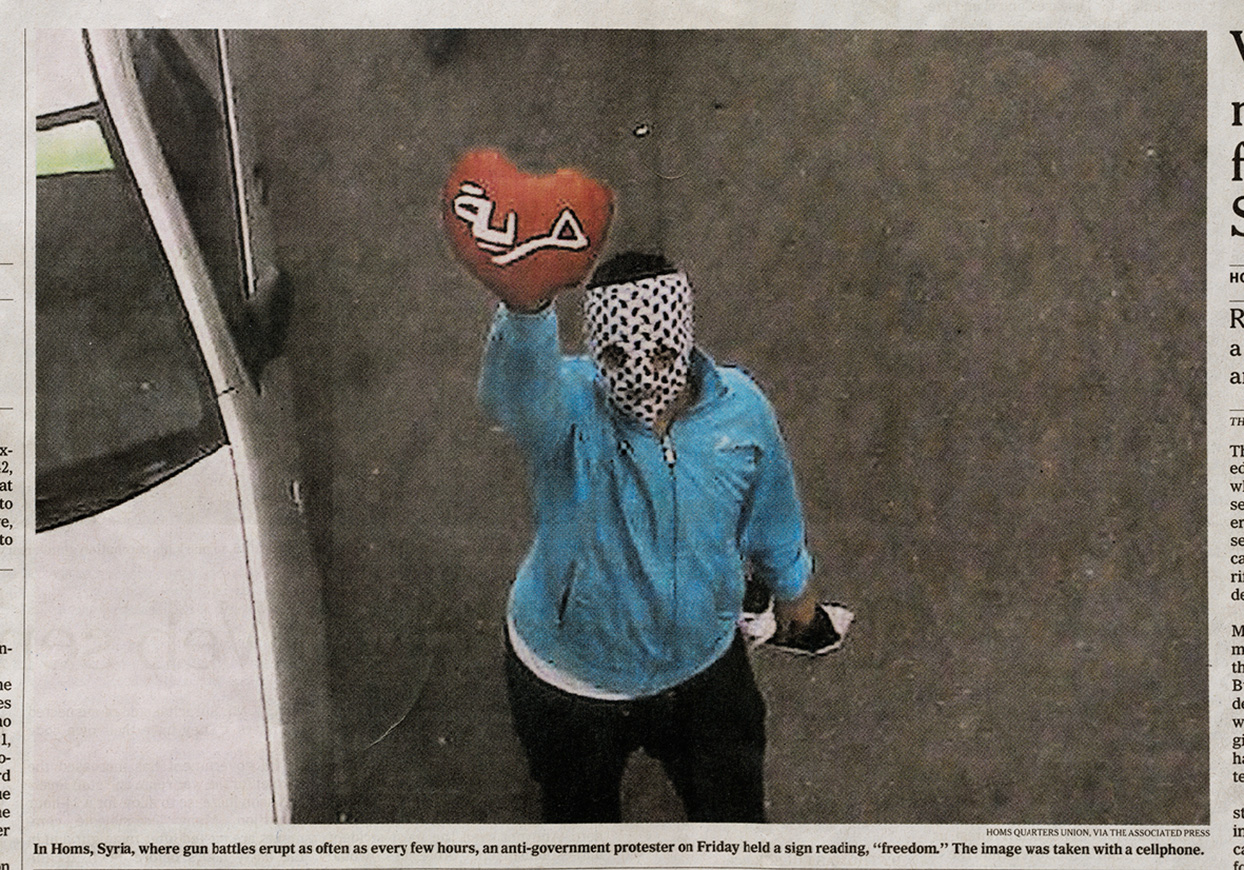

A Protester in Homs, Syria

January 1, 2013artist contribution,

Visual artist Florian Göttke investigates the function of public images and their relationship to social memory and politics. In this contribution, Göttke zooms in on the newspaper photograph of a Syrian protester to reflect on how images serve as a means of communication in our current mediatised society. He poses questions regarding the agency of the photographed subjects and the responsibility of the spectator.

On October 3rd, 2011, I open my morning paper and look down onto a street in Homs, Syria, directly into the eyes of a protester.

I look at him; he looks at me. His face is covered by a mask, but I can clearly see his eyes behind it. Our gazes meet, piercing through all of the intermediate layers of the media, in what feels like a live encounter. He looks at me with expectation: he poses a question; he makes a demand.

This sense, that we looked each other in the eye, that we became aware of each other’s presence and recognised each other’s existence is what Roland Barthes would have called the “punctum” of the photo – the force of which struck me at that moment. Now, the closer I look at this image, the less sure I am that his eyes are actually visible. Still I keep having the feeling that he is looking at me – maybe even more so because I can’t precisely determine the position of his eyes.

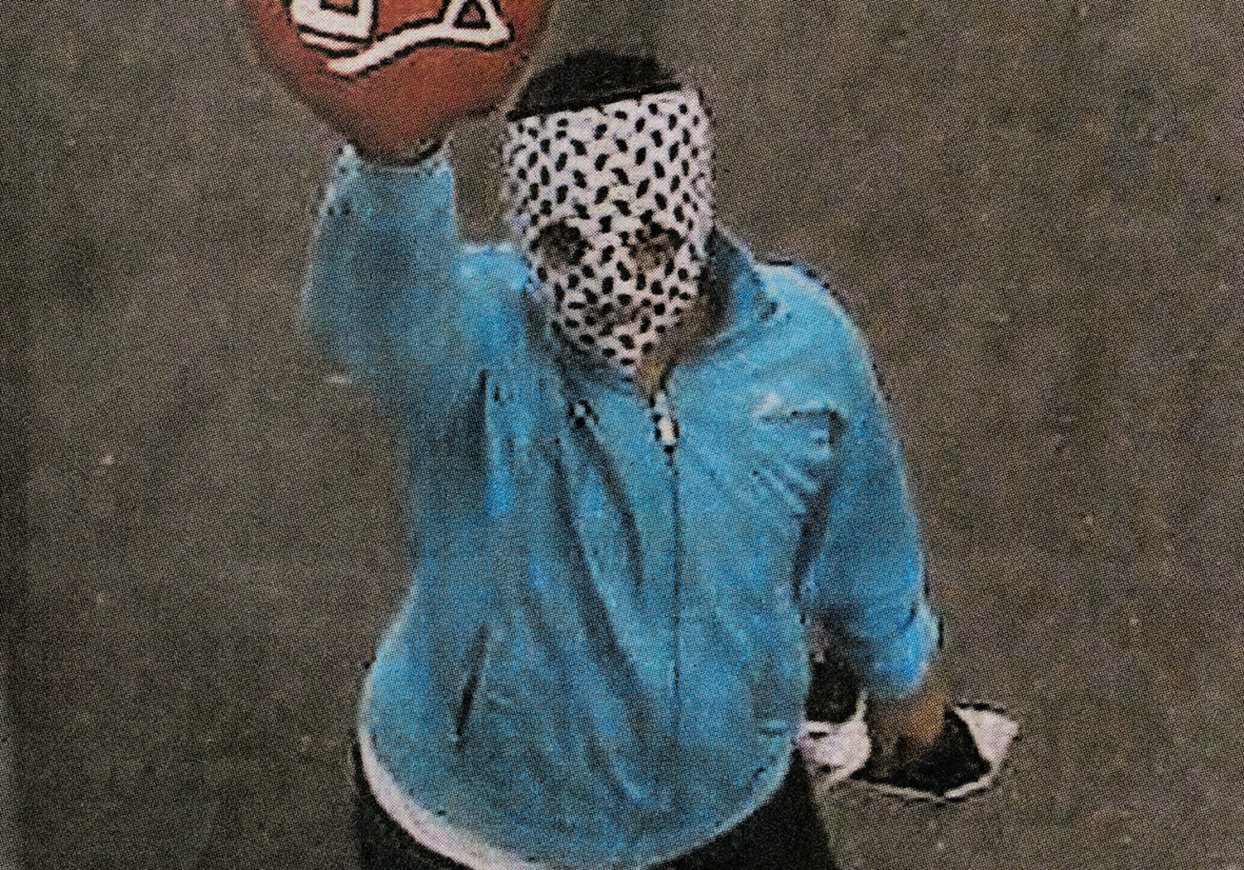

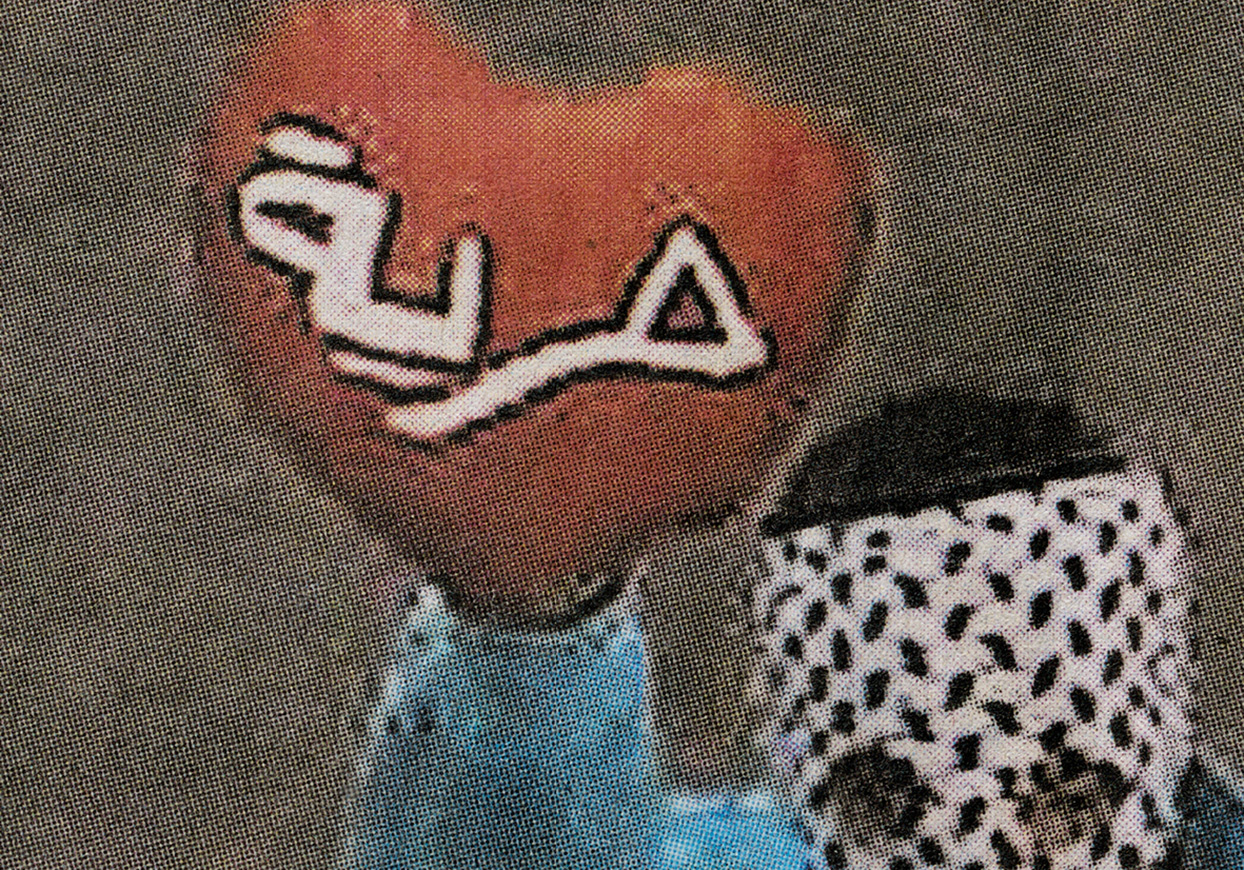

The mask covering his face reminds me of a Mexican wrestler’s mask — tightly fitted, transforming the face into one smooth surface. It seems to be handcrafted from a keffiyeh, a scarf symbolically linked to the Palestinian resistance, and that, in recent years, has also become a fashion item. The mask is as revealing as it is concealing; it hides the protester’s identity, but not his individuality. The sign he holds up to the camera is not a standard protest sign; it looks like a red velvet pillow in the shape of a heart, taken right off of his parent’s living room couch. It is emblazoned with a single word in Arabic: “freedom”. Love is his message and freedom his demand.

I spoke with a Syrian artist and learned that, at that time in shops across Syria, people had to show their ID to buy fabric and paint – the standard items necessary for making protest banners. To avoid police scrutiny, protesters in Syria creatively used other means: individually crafted protest signs scaled down from public square to camera-ready size, slogans written on the palm of hands, symbols painted on faces, cartoons drawn on pieces of paper – and the most unexpected protest sign: a red velvet cushion. I imagine it coming from a kitschy living room with a big overstuffed couch and countless pillows on it, the heart-shaped one being the most eye-catching and thus the most appropriate to adapt for the protest. It is quite impossible to determine from the photograph how the word was applied to the cushion. The letters could have been embroidered, painted on, stitched on, or glued to the pillow.

The protester is wearing a sky-blue tracksuit top and black pants. His sex is not easily determined. His somewhat rounded hips suggest he might be a woman, but this could be a distortion resulting from the camera perspective, and in the Arab-Middle Eastern context his short haircut makes it much more likely that he is a man. In his left hand, he is holding what might be a bag. The rest of the photograph is fairly empty: the surface of the asphalt, the hood and roof of a silver car. An uncropped version of the same photograph I found online shows the feet of four more protesters along the top edge of the photograph. Two of these four seem to be a couple of children together holding a sign with the Arabic text: “Yes for the Revolutionary City Council in Homs”.

I had a few discussions regarding the protester’s sex. While I couldn’t decide definitively, I also questioned its importance. The Syrian artist I talked to insisted that he was a man, most likely an activist, and that one of his female friends or family members had probably made the mask and the pillow for him. She insisted that protesting women would surely wear headscarves and the haircut conclusively identified him as a man.

The protester is not a passive subject being captured by a press photographer: he is active, playful and outspoken. He is taking charge; he is creating his own image. He performs his gesture for the camera in order to become a protest image. Together with the fellow citizen who photographs him from above he asks the audience to approve of his message: join the protest, and unite in efforts to oust Bashar al-Assad.

Making the photograph constitutes an act of protest as well: the picture and its message is made to be shared with friends, friends of friends and their multiplied followers in ever-widening circles. Photographed from a balcony or window above, the protester appears to be standing alone on the street. This perspective emphasises our idea of social media: a community of individuals. Each user makes his own choices and voices her own concerns individually. The protesters on the street thus appear not as a uniform mass but as a multitude. Through “Sharing”, “Liking” and “Friending” users become a community: an accumulation of individual statements that they hope will become big and strong enough to topple the regime.

We should not think of the protester and the photographer as two different types of actors. They share the same objective – and they share the risks that are inherent to engaging in opposition activities. The audience they seek is first and foremost not an international one, nor even that of their oppressive leader Bashar al-Assad. Primarily they are addressing each other: to share information and opinions, to posit ideas and to create community.

The protesters on the street, their fellow citizens observing them, together with their audience online create the “space of appearance”, a term coined by Hannah Arendt in her book The Human Condition. It is precisely here in this “space of appearance” created by the citizens for each other that the political is constituted. Even though in this case it is not the physical space of the agora, but a space once removed, the virtual space of social media.

The Arab Spring has been called the Facebook Revolution, and the virtual space of social media did facilitate the emergence of a “space of appearance” – where people were able to congregate as political subjects – and it is not a big step from being an active citizen to becoming an activist citizen, especially if the regime considers any dissent to be treason. But ultimately it was the people who came out of the virtual into the actual urban space – the people who protested in the streets – who changed the political constellations in their own countries.

The caption of the photograph reads: “In Homs, Syria, where gun battles erupt as often as every few hours, an anti-government protester on Friday held a sign reading ‘freedom’. The image was taken with a cellphone.” The photo is credited to “Homs Quarters Union, via The Associated Press”.

How this photograph made its way onto the front page of the International Herald Tribune is easy to imagine: the onlooker from the window or balcony photographed the masked man on the street and uploaded the picture to the Facebook page of Homs Quarters Union, a group of activists who established a media centre in order to support the protests and spread images and information about the Syrian uprising. The Associated Press, one of the largest news agencies in the world, must have gone to the Homs Quarters Union page, approached the group and brokered a deal to distribute the image on their behalf.

Upon closer scrutiny, the story isn’t that simple. I scoured the Homs Quarters Union Facebook page, but I was unable to find this image. I emailed the contact person and learned that they hadn’t produced the photo, and that they didn’t make an agreement with the Associated Press. Did the AP simply pluck a photograph from the Internet and credit it to one of the emerging grass-roots media centres to give it more credibility?

I contacted the AP to learn more about the image and its distribution. I never got an answer but they did refer me to the AP’s Dutch representative where I was able to buy the rights to the picture. I learned that the AP was only selling a cropped version of the image. Where the image came from and who cropped it remains a mystery. At the AP site, this image is labelled as a “handout” image, meaning that it was provided by a third party, that the agency cannot license the use of the picture and only bills for a handling fee. In this case, an image taken from Facebook can indeed be characterised as a handout image, because the primary interest of the activists is to share images and information and not to make a profit from them.

At that time, Syria was a difficult place to report from. The Syrian government had restricted the media’s access and had denied visas to foreign journalists since the beginning of the protests. Entering the country illegally with help from the opposition was possible but dangerous. Local media centres sprang up all across Syria to fill this gap and small groups of activists assumed the tasks of documenting the events, and collecting and disseminating the information.

The important question of agency comes into focus here. Most discussions about photography centre on the image itself: the effect of the image, its aesthetics, the intentions of the photographer, or society’s image saturation. This is also true for photojournalistic work, which claims to engage with people and their causes: it is the image that raises concerns, the photographs that make a cause visible, the photographer who bears witness, and the visibility of the cause that increases accountability and highlights the demands for humanitarian assistance.

The people shown in these photographs often function as stand-ins; they are passive victims and silent symbols. Their voices, their agency is habitually muted or ignored. Ariella Azoulay addresses this issue in her book The Civil Contract of Photography. She urges us to recognise and acknowledge that the people photographed in crisis situations have their own reasons for agreeing to be photographed and that their positions need to be taken into account.

Azoulay reconceptualizes photography as an active, public space and in so doing, aims to make it available for civic use, much in line with Hannah Arendt’s “space of appearance”. Azoulay posits that by engaging in photography – be it as a photographer, a photographed subject, or as a viewer – we enter a contract that connects us: we become citizens of photography. As a consequence of this reframing, we the viewers need to recognize that we actually have a relationship with and a responsibility for the people in crises we encounter in the media, people who are too-often denied participatory roles in their own societies and who don’t have recourse to address their grievances in regular civic procedures.

Outside of Syria, the information provided by citizen-journalists was eagerly picked up by the official news media. However, they never granted the activists the same level of authority as they gave their own correspondents. These images are always published with the disclaimer that the information contained in them could not be independently verified.

But what kind of independence can a photojournalist claim who is embedded either with a Syrian rebel group or government forces? One who is completely dependent upon their guidance in a quest for true images of the conflict? Does independence here not merely mean an assurance that the time and place of each photograph are accurate, while what is seen in the frame is impossible to evaluate, because it is influenced by too many incalculable factors?

This photo is clearly the statement of an activist involved in the situation, and here are many more of these active, activist citizens who continue to create and publish their own messages. This multitude of distinctive voices presents a counter-narrative to the standard reporting. It creates an alternative, upside-down, or rather bottom-up space of public discourse that is pluralistic, nuanced, ironic and defiant.

A very visible group of people in the small town of Kafranbel have been very effective in using the public space of the Internet to stage their protests: They photograph themselves with carefully formulated banners in Arabic as well as in English to reach as wide an audience as possible. Their equally sophisticated cartoons often allude to international pop culture and are easy to comprehend. They dispense their criticism equally between the Syrian regime, the supporters of the regime in neighbouring countries and in Russia, as well as the dabbling West.

On October 2nd, from the selection of images available that day, the picture editor at the New York Times chose this same image of the anti-government protester for the front page of the New York Times. A day later, the picture editor at the International Herald Tribune followed suit by republishing his colleague’s choice. But he decided to crop the photo even more tightly, erasing all traces of the other people in the frame so that the protester appears even more isolated. The image accompanied an in-depth article about the situation in Syria at a time when the struggle against Assad’s regime was just moving from a phase of largely peaceful protests and violent reactions from the security forces to outright civil war. With this photograph of the protester and his beaming red sign, the editor seemed to be urging us and all of the involved actors to pause and reflect on the course the warring parties in Syria were about to take and the possible consequences.

Subsequently, the photos that appeared in the newspaper returned to depicting the usual subjects: destroyed houses, dead bodies, funerals, opposition fighters in action, and refugees in miserable conditions.

The following morning, this newspaper image arrived on our doorsteps and entered our lives. From our breakfast tables we, the readers, looked down – right through the construct of the media – directly into the protester’s eyes on that fateful street in Homs. As our gazes met, they carried the intensity and actuality of a real encounter, even though we were thousands of kilometres apart. We, the public, had become the all-seeing, all-knowing eye of Google Earth gone live. We are now able to zoom in on any street on the planet to see what is happening there. This image allowed us to become eyewitnesses to the protests in Syria.

The visibility of the protester to us, a global public somehow suggests the possibility to limit the Syrian regime’s power and a certain degree of accountability. The wide distribution of recording devices and the easy access to global communication channels have made the world so transparent that abuse and atrocities can no longer remain invisible. Every deed, every event is photographed, recorded – if not in fact then as a possibility. Everything becomes visible; everything is in the public eye. This visibility urges us, the public, to act – to put a stop to the abuses and to demand consequences for the perpetrators.

But this gaze from above that suggests transparency and accountability is also the perspective of the surveillance camera, the spy satellite and the predator drone circling in the sky, observing every moving subject as a potential target. It is the gaze of the security apparatus that keeps an evermore-scrutinising eye on us. It is the systems of power that keep us in check, that immobilise us and prevent us from taking action.

We know the protester in Homs existed. He was there, alive and present in the one second when we first saw his image in the newspaper. But a second later he is already gone. We will never learn what happened to him in the struggle that has now turned into a bloody civil war. His image has been replaced by other images we find on the Internet: grainy videos that tumble to the dusty ground or suddenly turn black, testifying to their makers’ death by a sniper.

The sky above us is not empty anymore, but the hope for redemption is as fleeting as ever.

July 2013

Bibliography

- Arendt, Hannah, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998) (first published 1958)

- Azoulay, Ariella, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008)

- Azoulay, Ariella, Civil Imagination (London: Verso Books, 2012)

- Barthes, Roland, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981) (French: 1980)

- Freedberg, David, The Power of Images, Studies in the History and Theory of Response (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989)

- Hardt, Michael and Negri, Antonio, Multitude: Democracy in the Age of Empire (New York: The Penguin Press, 2004)

- Subcommandante Marcos, A Zapatista Position Paper on Photography (1996), www.nearbycafe.com (retrieved 5 Jan 2013)

- Mitchell, W.J.T., Cloning Terror, The War of Images from 9 / 11 to the Present (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010)

- Rosler, Martha, “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography)” in: Decoys and Disruptions, Selected Writings 1975–2001 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004)

- Sontag, Susan, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Penguin Books, 2004)

Florian Göttke is a visual artist based in Amsterdam. Since 2006 he is teaching at the Dutch Art Institute (DAI), Arnhem, about topics related to art and public issues. In his recent works he investigates the functioning of public images, and their relationship to social memory and politics. His lecture and book Toppled (Post Edition, Rotterdam, 2010), about the fallen statues of Saddam Hussein, is a critical study of image practices of appropriation and manipulation in our contemporary media society. Toppled was nominated for the Dutch Doc Award for documentary photography in 2011. Currently he is working on his PhD in Artistic Research “Burning Images – Genealogy of a Hybrid and Global Cultural and Political Practice” at the University of Amsterdam and the Dutch Art Institute, about the practice of hanging and burning effigies in political protests. See further: www.floriangoettke.com.