Cultural critic Brian Holmes explains how in communal space, which is determined more and more by technology, the privatization of knowledge continues to increase. Can language and communication still be meaningful in this context?

Now that neoliberalism seems to be in decline, Brian Holms wonders what this will mean for the emergence of Asian biennials. In reference to the concept of the sixth Taipei Biennial – undeniably a neoliberal stronghold – and a few of the works of art presented there, he discovers possibilities to imbue this transcontinental exchange with new meaning on various scale levels.

Cultural critic Brian Holmes analyses the genesis of the distributional machinery of intermodal transport that circulates commodities through the global economy. What are the implications for our way of life, both for people tied to a particular area and for migrants? Is it possible to escape capitalism’s laws of motion?

How do we confront the triple crisis that has beset the economy, the environment and civil peace?

The British culture critic and activist Brian Holmes claims that the imprint of artistic experimentation on social protest movements is undeniable. He examines the notion of process as that which experimental art and activism have in common. Holmes analyses the exodus, mass defection, as a means of escaping the immobilizing transparency of the mediated democracies, as a way to resist politics-as-usual.

Brian Holmes is a cultural critic living in Paris and Chicago. He holds a doctorate in Romance Languages and Literatures from the University of California at Berkeley, was a member of the editorial collective of the French journal Multitudes from 2003 to 2008, and has published a collection of texts on art and social movements entitled Unleashing the Collective Phantoms: Essays in Reverse Imagineering (New York: Autonomedia, 2007). His book Escape the Overcode: Activist Art in the Control Society is available in full at brianholmes.wordpress.com. Holmes was awarded the Vilém Flusser Prize for Theory at Transmediale in Berlin in 2009.

Using the ideas of Gabriel Tarde, Ludwig Wittgenstein and George Herbert Mead, writer and critic Stephan Wright reflects on the question of how, in a capitalist knowledge economy, to prevent intellectual property from being commodified and knowledge from becoming increasingly privatized.

In the modern era, publicity is often depicted as the leading principle of political and social representation, in which there is no longer any room for secrecy. This is a myth, according to the Viennese philosopher Stefan Nowontny. Publicity and secrecy are – through the production of affects – more entangled than ever in an inextricable knot.

Stefan Nowotny is a philosopher based in Vienna. He has published widely, especially on philosophical and political topics and currently mainly works on the research project Europe as a Translational Space. The Politics of Heterolinguality carried out by the EIPCP. See further: www.eipcp.net.

Media theorist Boris Groys analyses the significance of WikiLeaks against the background of the democratic need for universal openness and communication. In doing so, he makes a remarkable observation: WikiLeaks’ universal openness is based on total concealment, and this makes it a first example of a truly postmodern universal conspiracy. By devoting itself to being a universal, administrative service in the form of a conspiracy, WikiLeaks is not only a historic innovation – it also runs a great risk.

Art philosopher Boris Groys sees the art installation as a way of making hidden reality visible. The ambiguous meaning of the notion of freedom that Groys observes in our democratic order is also present in the contemporary art installation. This can be exposed by examining it and analysing the role of the artist and the curator. The public space created by the installation, and by the biennial, is the model for a new political world order.

Boris Groys is since 2009 a Full Professor of Russian and Slavic Studies at New York University, New York. As of December 2009, he is also a Senior Research Fellow at the Academy of Design in Karlsruhe, Germany. He additionally curates various exhibitions and publishes articles and books, including Art Power (2008), Going Public (2010) and Introduction to Antiphilosophy (2012).

According to American political theorist Jodi Dean, WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange lacks insight into the setting in which he operates. In communicative capitalism, the whole concept of the relation between openness and democracy radically changed. Not only does Assange assume that reliable, symbolically effective information is the basis of democracy, he also does not recognize that information overkill is a greater handicap than too little information, and that he himself is part of the spectacle that is diverting attention from political issues.

Political theorist Jodi Dean asserts that Jonathan Lethem’s novel Dissident Gardens (2013) “gives communism a body where we can again feel its beating heart”. She describes how Lethem “lets us sense the continued vibrancy of communist desire on the left despite the absence of a party.”

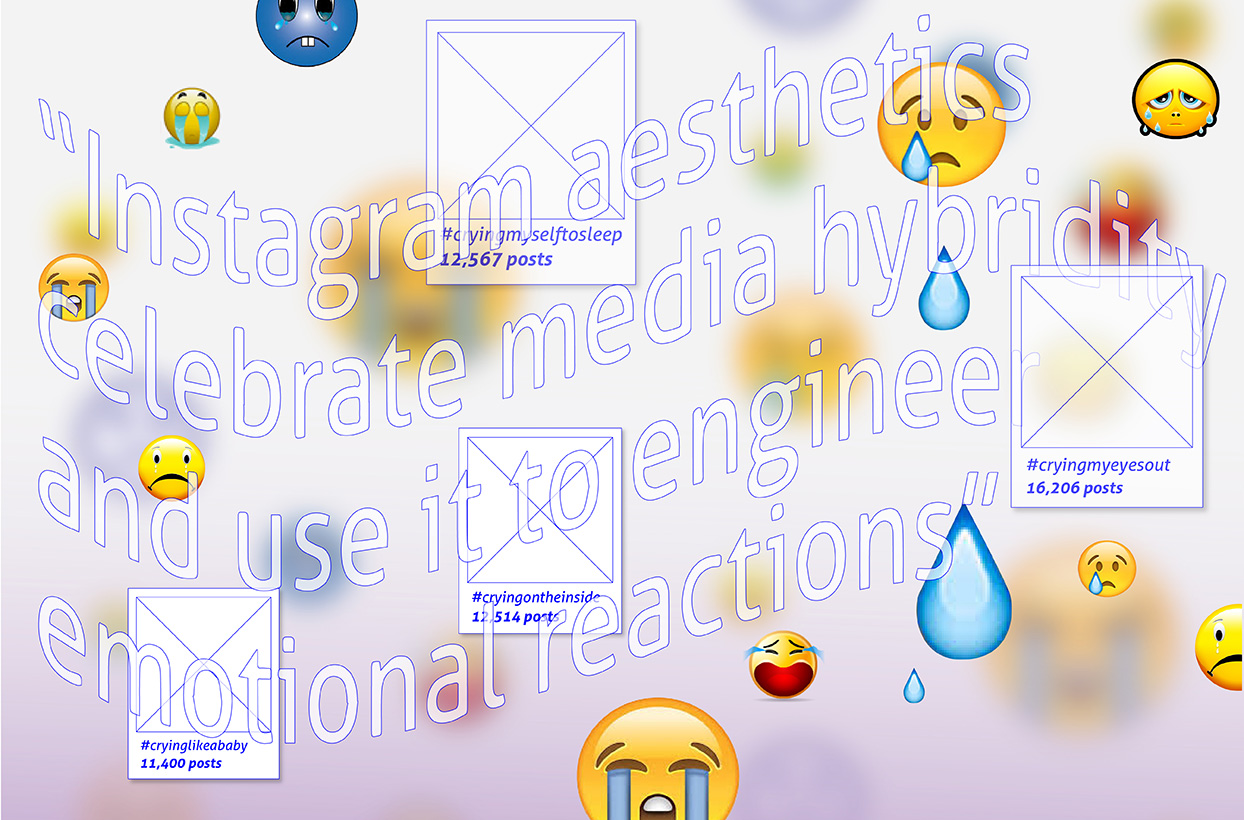

Once we accept that capitalism is communicative and communications are capitalist, where might we find openings for critique, opportunities for resistance and possibilities to break free, Jodi Dean asks? She sees one answer appearing in the commoning of faces, a practice that emerges out of the communicative practices of mass social and personal media. To explore this commoning, she develops the idea of ‘secondary visuality’ as a feature of communicative capitalism. Reflecting on the repetition of images and circulation of photos, Dean presents secondary visuality as an effect of communication that blends together speech, writing and image into something irreducible to its components, something new.

Jodi Dean is the author of numerous books and articles. Her books include Solidarity of Strangers (1996), Aliens in America (1998), Publicity's Secret (2002), Žižek's Politics (2006), Democracy and Other Neoliberal Fantasies (2009), Blog Theory (2010) and The Communist Horizon (2012). Her most recent book is Crowds and Party, published by Verso in 2016.

Marco Scotini is the curator of the ongoing Disobedience Archive project, a video station and discussion platform that focuses on the relationship between artistic practices and political action. In this text, Scotini focuses on the Autonomia movement of 1977 and the Italian underground filmmaker Alberto Grifi, who is considered a cinema pioneer who anticipated contemporary disobedience cinema. Scotini analyses Grifi’s film Festival of the Young Proletariat at Parco Lambro and offers his reflections on social disobedience in relation to mediatisation and representation.

Marco Scotini is an independent curator and art critic based in Milan. He is Director of the department of Visual Arts and Director of the MA of Visual Arts and Curatorial Studies at NABA in Milan. He is Editor-in-Chief of the magazine No Order. Art in a Post-Fordist Society (Archive Books, Berlin) and Director of the Gianni Colombo Archive (Milan). He is one of the founding members of Isola Art and Community Center in Milan. His writings can be found in periodicals such as Moscow Art Magazine, Springerin, Domus, Manifesta Journal, Kaleidoscope, Brumaria, Chto Delat? / What is to be done?, and Alfabeta2. Recent exhibitions include the ongoing project Disobedience Archive (Berlin, Mexico DF, Nottingham, Bucharest, Atlanta, Boston, Umea, Copenhagen, Turin 2005–2013), A History of Irritated Material (Raven Row, London 2010) co-curated with Lars Bang Larsen and Gianni Colombo (Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 2009), co-curated with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. He has curated solo shows and retrospective exhibitions of Santiago Sierra, Deimantas Narkevicius, Jaan Toomik, Ion Grigorescu, Regina Josè Galindo, Gianni Motti, Anibal Lopez, Said Atabekov, Vangelis Vlahos, Maria Papadimitriou, Armando Lulaj, Bert Theis and many others. His most recent exhibition was Disobedience Archive (The Republic) for the Castello di Rivoli (Turin) and he is currently working on an exhibition project dedicated to the art from Eastern Europe, to be opened in January 2014 in Bologna.

The Italian-French sociologist Maurizio Lazzarato uses Foucault’s concept of ‘pastoral power’ to analyse the demise of the separation between public and private space. Furthermore, his study of the social policies concerning unemployment shows how ‘the production of guilt’ is more and more often being used as a strategy; a process already described by Franz Kafka in his literature.

Maurizio Lazzarato is a sociologist and member of the editorial staff of the magazine Multitudes. He lives and works in Paris. 1996 saw the publication of his famous essay ‘Immaterial Labour’, whose theme he further developed in Lavoro Immateriale. Forme di vita e produzione di soggettività (Verona), which appeared a year later.

Privacy is a defensive right that protects a person’s private life. However, the ‘right to be left alone’ is not just a legal but also a political and social construction. Therefore, this is a concept that, although established by law, can be experienced and observed differently by individuals and groups, depending upon their position in society and the desires and interests attendant upon that. For instance, privacy can be an urgent topic for civil rights movements, whereas citizens apparently are less bothered about it. And so more and more government measures can be taken and new technologies applied that conflict with the right of privacy but which are used in a relatively unconcerned way or submitted to with hardly a whisper of protest.

Whether this be an endangered basic right, an obsolete concept of the enlightenment, a lost cause or an activists’ obsession, the traditional notion of privacy has largely been undermined in today’s security and information society. This certainly is the result of a preventive government policy that is out to control the comings and goings of citizens, and a commercial sector that, off-line and online, tries to get more and more of a handle on the individual desires and consumption patterns of customers through its clever registration devices. But there is more going on: people are having less and less qualms about voluntarily revealing personal information in the media and on the Internet. The protection of privacy seems to be subordinate to people’s desire to manifest themselves publically in society. In the globalized network cultures, visibility, transparency, accessibility and connectivity are what count. These values are at odds with the idea of privacy as ‘secluded from the rest’. Does this imply that ‘everyone belongs to everyone else’ to an increasing extent, as in Huxley’s dystopic Brave New World (1932)? Or, these many years after The Fall of Public Man (Richard Sennett, 1974) are we experiencing ‘the fall of private man’ – from which we could then conclude that the public-private antithesis has lost its force as a signifier of meaning? Are alternative subjectivities and rights emerging that are considered more important in the twenty-first century? Are new strategies and tactics being mobilized to safeguard personal autonomy and to escape forms of institutional biopower?

In Open 19, the concept of privacy is examined and reconsidered from different perspectives: legal, sociological, media theoretical and activist. Rather than deploring the loss of privacy, the main focus is on the attempt, starting from our present position of ‘post-privacy’, to gain an idea of what is on the horizon in terms of new subjectivities and power constructions. Naturally, this cannot be investigated without paying attention to the sociopolitical and technological violations of privacy that are going on at present.

Daniel Solove, law professor, proposes that privacy be considered as a pluralistic concept with a social significance. A theory on privacy should be directed at the very problems that create a need for privacy, according to Solove. Maurizio Lazzarato, taking Foucault’s concept of ‘pastoral power’ as an example, analyses how the state wields power techniques to control the users of social services, and how it intervenes in the lives of individuals in doing so. Sociologist Rudi Laermans goes into the implications of the ideal of transparent communication for secrecy and personal privacy.

In search of effective strategies against the surveillance regime, Armin Medosch, media artist and researcher, has developed a model in which he couples the historical function of privacy in a free democracy with the overall technopolitical dynamics. Felix Stalder examines today’s ‘post-privacy’ situation, in which a change is taking place in how people achieve autonomy, and how institutions and corporations exercise control over them.

In the column, Joris van Hoboken, member of the board at Bits of Freedom, challengingly states: ‘Privacy is dead. Get over it.’ Oliver Leistert uses a post-Fordian framework in criticizing the German protest movement AK-Vorrat, which focuses on issues concerning data retention and privacy from a liberal democratic standpoint. Martijn de Waal considers the concrete possibilities of using locational data from cellular networks for civil society projects and the questions on privacy that this raises. In the light of contemporary computer paradigms like the Internet of Things, Rob van Kranenburg argues in favour of making concepts of privacy operational from the bottom up in the infrastructure of technologies and networks that connect us with one another in our environment.

Mark Shepard has made a contribution on ‘The Sentient City Survival Kit’, his research project in the area of design, which proposes playful and ironic technosocial artefacts that investigate the consequences that the observing, evermore efficiently and excessively coded city has for privacy and autonomy. Matthijs Bouw, architect and director of One Architecture, investigates privatization and privacy in the context of the Internet platform ‘New Map of Tbilisi’. With photos by Gio Sumbadze and Lucas Zoutendijk, he shows how the ‘wild capitalism’ of the new Georgia has led to a reduction of privacy in Tbilisi.

Recent years have seen a politicization of the ‘common’ in the public domain. This intensification of the debate stems from a growing number of conflicts between public and private with respect to the ownership and control of knowledge and culture. ‘Freedom of culture’ has become a pressing issue with both legal and ethical ramifications: it concerns the extent to which culture and knowledge can be freely distributed, exchanged or appropriated, and the guarantee of places where the ‘commons’ can manifest themselves and be discussed.

The expansion of restrictive legislation relating to copyright and intellectual property, as well as the increasingly inaccessible technical architecture of the Internet, the source codes, are jointly responsible for the rise of movements or initiatives such as Free Software, Open Source, Libre Commons, Copyleft, Free Culture and Creative Commons, projects which differ widely with regard to politics, philosophy and chosen strategy, but which all interpret ‘free’ as ‘free as in free speech, not free beer’. The activists in particular are concerned not merely with fighting copyrights or creating alternative licences and free spaces, but with realizing a social vision. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, for example, argue in their writings about power and the masses in an era of globalization, for an ‘an open-source society, that is, a society whose source code is revealed so that we can all work collaboratively to solve its bugs and create new, better social programmes’.

Concepts like originality, authorship and ownership were already being explored in art and philosophy in the 1970s and ’80s, at which time ‘appropriation’ became an explicit figure of speech. Compared with the massive scale on which culture is being appropriated and exchanged today, due in no small part to digitization, this now looks more like a symbolic, intellectual and elitist affair, more like an artistic project than a social strategy. But the flip side of today’s ‘free culture’ is a growing measure of regulation and control in which some people discern the contours of a ‘permission culture’. At the same time, there is a growing tendency to outsource elements of public culture to private parties (patrons, corporations and the like) who are then able to co-determine what will be released or made publicly accessible and what not.

Open 12 examines the consequences of these developments for the ‘free’ realization and exchange of culture, the dynamism of art and the balance of power in the public domain and urban space. It looks at new restrictions but also at new possibilities. The emphasis is on questions surrounding the privatization of intellectual property on the one hand, and on public space as creative practice on the other.

Stephen Wright ponders what the growing privatization of knowledge means for art as a form of knowledge. Brian Holmes also looks at the privatization of knowledge, but in relation to the collective, technologically determined space in which language and communication acquire meaning. McKenzie Wark, author of A Hacker Manifesto and Gamer Theory, describes the adventure of publishing his books in light of his own theory. Joost Smiers criticizes the current copyright system and leading alternatives like General Public License and Creative Commons. He puts forward an alternative proposal for returning ‘to the commons what has always belonged to it’. Willem van Weelden questions the effectiveness of the activist credo of ‘becoming minor’ in relation to Net criticism of Lawrence Lessig and Creative Commons.

In ‘Artistic Freedom and Globalization’, Pascal Gielen seeks to return art to a role that encourages reflection and argues for the creation of a free zone that would entail accepting globalization in all its complexity. Maxine Kopsa interviews British artist Chris Evans about his project Militant Bourgeois: An Existential Retreat, which focuses on the area of tension between patronage (in particular the increasingly criticized Dutch system of government grants) and the contemporary production of art. In his column, Arjen Mulder states that ‘an artist doesn’t live on in his oeuvre, but in his fakes’.

Architect Dennis Kaspori collaborated with Jeanne van Heeswijk on a supplement entitled ‘Guest ≠ Welcome’ in which they react to the discourse of segregation in urban space with new models for care and hospitality aimed at developing a better understanding of the fragile situation in which the residents of the so-called Zones Urbaines Sensibles find themselves, and at devising more inclusive forms of urbanity. They invited a number of international firms and initiatives to present a vision based on their own practice.

Swop Network’s contribution, ‘Give Away in Circulation’, challenges the notion of intellectual property, while artist Oliver Ressler gives a special presentation of his project Alternative Economics, Alternative Societies.

Taking WikiLeaks as an illustrative example, Open 22 investigates how transparency and secrecy relate to one another, to the public and to publicity in our computerized visual cultures. This issue continues to explore what for Open are fundamental themes such as privatization, mediatization and the demand for the communal. In the more general sense, it examines transparency as an ideology, the ideal of the free flow of information versus the fight over access to information and the intrinsic connection between publicity and secrecy. It also tries to come to grips with the social and political implications of the phenomenon of WikiLeaks, which, with the illustrious Julian Assange as front man, produces an effect on a global scale. While most people would agree that WikiLeaks has started something that is unstoppable; there is hardly any consensus on its morality, effectiveness or strategy, neither in conservative nor in progressive circles.

WikiLeaks, as the counterpart of the ‘transparent’ citizen or consumer, expresses a growing public desire for openness and transparency as regards the state, businesses and administrators – a demand for publicity that is continually fed by floods of sensational social and political revelations. And whereas people often consider secrecy within the public sphere to be inadmissible and clandestine, transparency is associated with democracy, participation and accessibility. But does transparency only work in a liberating way? Can it not equally have a concealing or controlling effect? Aren’t certain forms of transparency actually the manifestation of the banality of the contemporary spectacle, which revolves around pure display and the production of affects?

In any case, with their capacity to immediately reproduce and disseminate information, the media play a crucial role in the social process of displaying and disclosing. But on behalf of whom are they doing this, and for whom? Do they not increasingly form an abstract power?

Two introductory essays explore political and social notions of transparency and secrecy. Media theorist Felix Stalder searches for a form of transparency that is not employed as a means of power and control, such as in neoliberal market thinking, but that can express and strengthen social solidarity. Stefan Nowotny, philosopher, goes into publicity and openness as a modern myth in relation to the production of affects and the exercise of power, and finds that secrecy and publicity are intertwined more than ever.

Other pieces directly examine WikiLeaks and its implications. Philosopher and media theorist Boris Groys argues that WikiLeaks’ democratic universal openness is based on the most absolute secretiveness, and as a matter of fact is a conspiracy. The American political theorist Jodi Dean shows herself to be extremely critical about WikiLeaks, stating that too much information is a greater handicap than too little information in ‘communicative capitalism’ and that Julian Assange, by becoming a star in his own story, takes attention away from the political issues he says he wants to bring to the public’s attention. The interview conducted by Willem van Weelden, researcher-publicist on interactive media, with media theorist Geert Lovink and political scientist/sociologist Merijn Oudenampsen goes into the question of whether and how WikiLeaks brings about social and political change, and what the platform means for contemporary forms of art and activism. In the column, Jorinde Seijdel wonders where WikiLeaks and Facebook converge, seeing as both avow transparency as their ideology but apparently out of very different motives.

Transparency and secrecy are also relevant concepts in art and architecture. The art historian Roel Griffioen posits that, analogous to social developments, the ideal of the glass house in modern and contemporary architecture has made way for the house of one-way glass, in which concealing has become just as important as displaying. Art theorist Sven Lütticken discusses how the structure of the modern art work offers the perfect means of gaining insight into the dialectics of opacity and transparency in this age of public secrets. The work of Amsterdam-based American artist Zachary Formwalt, who also made a special visual contribution to this issue, is one example of this.

This issue features a number of excerpts from Failed States, a manuscript-in-progress by American artist Jill Magid that investigates transparency and secrecy out of Magid’s desire to be an eyewitness to the ‘war on terror’ and the media’s representation of it. British artist Heath Bunting contributed a fold-out flowchart that explores the porous borders between the individual, their ‘data body’ and corporations.

Illustrations of a project by designer Floor Koomen and graphic design students of the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam can be found throughout this issue. The assignment consisted of selecting a leak from the WikiLeaks website and editing and designing it for a print-on-demand publication, thus providing us with a critical look at WikiLeaks as a medium and the current position of journalism. (see: www.orderyourwikileak.org)

In the light of a critical examination of today’s transparency ideologies, comparing Facebook and WikiLeaks with each other in a basic manner is surprisingly clarifying. At first, this might seem inappropriate, because of the apparently fundamentally different premises and divergent social, economic and political views of these super-topical digital platforms: Facebook as an ultra-capitalistic billion-dollar company versus WikiLeaks as an activist, non-profit organization; Facebook as a social network for the exchange of personal information versus WikiLeaks as a whistle-blower site for anonymous revelations of public interest; Facebook as commercial purloiner and trader of information versus WikiLeaks as altruistic provider of information.

There are also many similarities, however: both Facebook and WikiLeaks are to a large degree products of an increased societal desire for disclosure. Both seek their societal legitimization in the philosophy (or doctrine) of transparency and the sharing of information, and on the basis of that, both preach a better world – whereby ‘Julian Assange sees the world as filled with real and imagined enemies; Zuckerberg sees the world as filled with potential friends’, as Time Magazine once put it. In their fanatical creed of transparency, both organizations have also been accused of serious violations of people’s privacy (despite WikiLeaks’ position that transparency is something for government and not for individuals), while both Zuckerberg and Assange seem to actually encourage a certain mystification as regards their own person. Last but not least, both claim a significant role as stoker of the revolutions in the Middle East. In that regard, however, Assange, who considers WikiLeaks a check on power, called Facebook an ‘appalling spy machine’ for the American government and its intelligence services. Zuckerberg, on the other hand, does see ideological similarities ‘somewhere’: ‘At a higher level some of the themes may be connected.’

Be that as it may, somewhere in the shining clarity of radical transparency there is an acute black hole, a dark spot where Facebook and WikiLeaks meet. The question is: At that frightful point of convergence, what happens with the first resumed differences? Are they confirmed after a fleeting contact, so that a process of semantic and ideological divergence can immediately resume, or might it be revealed that these podiums indeed both are a special kind of ‘service’, proceeding from their dedication to transparency? And then here the word ‘service’ is also meant in the sense of ‘celebration’ or ‘cult’. But who or what is being served, and if this is a cult, what is being worshiped or celebrated?

At first sight, of course, this seems to be a cult of visibility, whereby Facebook and WikiLeaks, in their craving for universality, complement one another as counterparts: the former involves the ‘community’ in the celebration and the latter its institutes; both must be transparent. In this immense transparent bliss, the communal is then celebrated and claimed, as one big discourse and a democratic exchange, whereby an immaterial, intangible service is provided to the populus, a service that it carries out itself, as a higher specimen of Do-It-Yourself. DIY in the sense that it is the ‘populist body’ itself that produces (by sharing and by publishing) the experience of transparency and communis, which it then digests and consumes.

So in fact, the communal is also what is ‘drawn up’ and offered in this cult, and what disappears into the all-absorbing black hole of hyper-transparency. And so this concerns a service to visibility and openness just as much as to secrecy. The core of the communal and public can thus never be situated purely in the visible and transparent, but is equally present in the hidden and opaque. (In this light, it is understandable that the central focus in the new reality programmes, such as Secret Story, is on keeping a secret, instead of exacting extreme transparency from the participants.)

Thus the contrived search for a point of convergence between Facebook and WikiLeaks as a small thought experiment at any rate results in the realization that, despite their differing ideologies and objectives, the paradigms underlying these two organizations are not essentially different. On the contrary, it is precisely together that they manifest the dominant paradigm to which the demand for transparency belongs in optima forma. They equally well demonstrate together, as counterparts of one another, that the philosophy of transparency and its logistic or performative system not only makes the communal visible but also makes it evaporate and lets it escape.

‘Some may have forgotten, but politics still always is imagination, the capacity to dream collectively, to tell stories; politics still always accommodates a form of mythology. If we want to take populism seriously as a political force, we must above all consider it in the light of these aspects. At the same time, we must ask ourselves the difficult question of why our own politics no longer can appeal to the imagination.’ With this provocative statement, guest editor Merijn Oudenampsen sums up the theme of Open 20 in his introductory essay. Sociologist / political scientist Oudenampsen (b. 1979, Amsterdam) conducts research on Dutch populism, and among other things is working on a book on populism and the politics of symbols. He is also the editor of www.flexmens.org, which reports on ‘everything that makes life unpredictable – migration, war, art, crisis, modernity, and the housing market’. Perhaps someone of his generation is precisely the one who should pose this urgent question about politics and the imagination, someone who can go beyond the moral, rational and politically correct standpoints of traditional criticism, and far beyond the protest generation of 1968, in considering and questioning the current populist spectacle.

In the Netherlands, the formation of a new cabinet has been going on for months at the time of this writing, not lastly because of the prominent position that populist Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom (PVV) have acquired in the formation process. However, this issue of Open is not specifically about populism in the Netherlands, but also about its current manifestations in the USA (the Tea Party) and Italy (Berlusconi and the Lega Nord), and about the success of left-wing populism in Latin America. The contributions steer clear of the often all-too-easy moral evaluations of populist party programmes, or of passing judgments on populist leaders. Populism is not regarded here as a ‘sickness’, as Le Monde recently opined in a piece on the political situation in the Low Lands, but as a manifestation of the need for a politics that is not merely based on ‘public management and a rational assessment of interests’ (Oudenampsen). People have a desire for a new political discourse with room for the imaginary and for appealing stories. Not as a denial or simplification of the complex social reality, but as a recognition of its mythical quality. This irrevocably concerns the failure of modern politics, the emptiness of Western democracy, xenophobia, neoliberalism and the role of the media. But above all, this issue of Open is a plea for a more imaginative politics that emphasizes the importance of new, ‘creative’ ways of thinking.

Thus the American sociologist Stephen Duncombe argues for a dreampolitik. Politics should be the art of the impossible, says Duncombe, and for this we need tools and methods that inspire people to dream themselves, instead of being subject to the dreams of their leaders. He shows how the artists / activists the Yes Men and Steve Lambert organize ‘political acts of imagination’ that simultaneously shake people awake and give them an opportunity to momentarily drift off into a dream world. The Italian theorists Franco Berardi and Marco Jacquemet go into Berlusconi’s media populism and explain his success through a historically determined religious-cultural undercurrent, in which the image is divine. Political scientist Jolle Demmers and writer Sameer S. Mehendale analyse how, in the Netherlands, fantasizing about purity and moralizing over culture and citizenship has interacted with the neoliberal market and the media in giving rise to xenophobia.

Yves Citton, literary theorist, pleads the case for new emancipatory myths as a way out of the capitalist system, seen as crisis and not as being in crisis. Rudi Laermans’ interview with the Argentinean political theorist Ernesto Laclau, author of On Populist Reason (2005) covers Latin American left-wing populism and populism as an inherent dimension of a democratic politics. In the column, British philosopher Nina Power declares that we must again appropriate the concept of ‘popularity’ as a way of countering the depressing populism we currently are witnessing. In a discussion on mythopoesis, the Italian writers’ collective Wu Ming critically assesses its activist role in the demonstrations against the G8 summit and the IMF in Genoa in 2001.

Aukje van Rooden, Dutch philosopher, says that the greatest myth of our contemporary politics is the assumption that it can function without a mythological structure. The rise of populist politicians is accommodated by this faulty myth, according to Van Rooden. Sociologist Willem Schinkel contends that populism should not be considered a threat to democracy. In a time of radical depoliticization, populism is valuable as a mnemonic technique, a reminder of the political, states Schinkel.

In the pictorial / written contribution by the graphic design and research bureau Foundland, graphic design is employed as a way of researching the symbolism and media representation of populism and its leaders. In collaboration with anthropologist Lynda Dematteo, Italian graphic designer Luisa Lorenza Corna analyses the visual strategies of the populist movement Lega Nord.

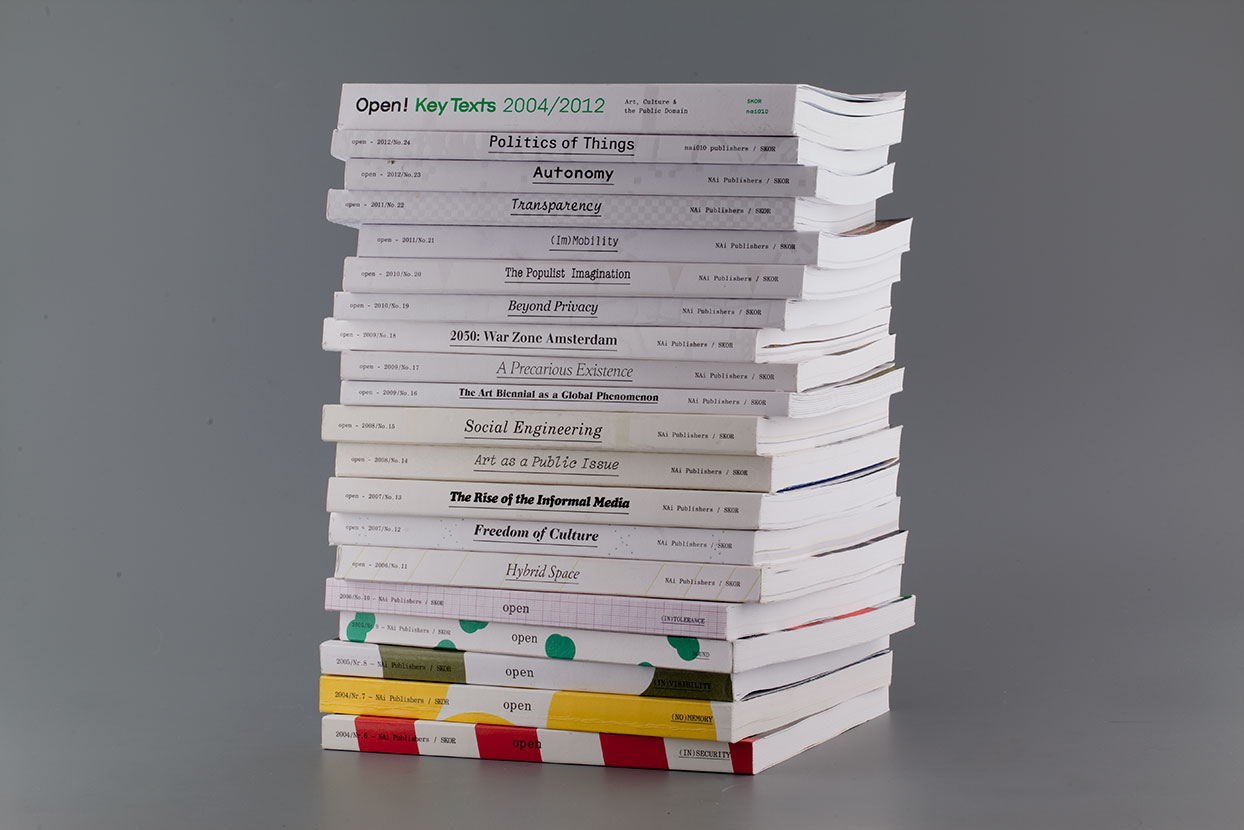

This extra issue of Open is published in honour of the cahier’s fifth anniversary and has come about in close collaboration with guest editor Pascal Gielen. At the time of the first Brussels Biennial, Gielen organized a programme of lectures and debates in Brussels on 19 October 2008, focussing on the art biennial as a global phenomenon. The programme was put together in cooperation with the Flemish-Dutch House deBuren in Brussels, the Flemish institute for visual, audiovisual and media art (BAM) and Gielen’s own Lectorate in Arts in Society at the Fontys College for the Arts. The debates looked at the boom in international art biennials – at the moment there are hundreds of biennials active all over the world. They also considered how the art biennial, which was originally an instrument within a politics of nation-states, is increasingly deployed for developing and marketing cities and regions. In order to compensate for this, biennials often put political issues onto their artistic agenda. The recurring question is Brussels was: can biennials really represent an alternative political voice in these neo-political times?

The philosophers Chantal Mouffe, Michael Hardt and Boris Groys and the curators Molly Nesbit, Charles Esche and Maria Hlavajova talked about the biennial as model, concept and instrument, and about the geopolitical, sociocultural and economic space in which it manifests itself. Some of the lectures formed the basis for this special edition of Open which this time is appearing without its regular features. Supplemented with an introductory essay by Pascal Gielen, new essays by Brian Holmes, Irit Rogoff and Simon Sheikh and with the republication of an exemplary text by Thierry De Duve, a ‘reader’ has been created in which the art biennial as a global phenomenon is analysed and approached not only in terms of an art theoretical discourse or curatorial practice, but also on the basis of more sociological and political-philosophical discourses. Some essays deal directly with the biennial, while other essays, such as those of Hardt and Mouffe, reveal different conditions and relationships within the social and political reality that the biennial is part of, putting forward proposals and posing questions that could be addressed by art and its scene. The result of the reflections and propositions in Open 16 is by no means unequivocal, but all the ‘strategies in neo-political times’ that are articulated express the urgency of not taking the biennial as a global phenomenon for granted. There are also signs of a shared awareness that it cannot be regarded separately from the logic of neoliberal markets.

In the context of Open as a series of anthologies in which the changing conditions of the public domain are examined from a cultural perspective, the subject of the biennial represents a possibility to look at the way in which this phenomenon and its legitimizing discourses relate to ideas about the city and urban politics, to new notions of publicness and to the implications of processes such as globalization and mediatization. The editors of Open are grateful to Pascal Gielen for his generous commitment as guest editor. Our great thanks are also extended to the co-producers of Open 16: Dorian van der Brempt, director of deBuren; Dirk de Wit at BAM; and Fontys College of Fine and Performing Arts. Last but not least, we are grateful to SKOR for allowing us the editorial freedom to develop Open as a series.

This issue came into being in collaboration with guest editor Eric Kluitenberg, a media theorist, writer and organizer of projects concentrating on culture and technology. In 2010, Kluitenberg organized the ‘ElectroSmog International Festival for Sustainable Immobility’. ElectroSmog arose out of criticism of the ‘growing worldwide mobility crisis’ and began as a ‘search for an alternative lifestyle that is no longer dominated by speed and continuous mobility’. The festival took place in several international cities simultaneously and was streamed live on the Internet. The idea that communications technology can resolve the conflict between ecology and mobility was by no means confirmed during ElectroSmog, but once again problematized, not in the last place by the recognition of different ‘regimes of mobility’ that are active on the local and global levels and affect one another.

Sustainability and ecology is merely one dimension of mobility as a social question. In the light of globalization, the new technology and sociopolitical developments on the local and global levels, it is equally about mobility versus immobility in terms of people, data, capital and products. It is also about mobility privileges and the freedom of movement, or lack thereof, of population groups and individuals, about incessant flows of data, the enticements of capital and free commodity markets.

This issue of Open explores the internal contradictions of prevailing mobility regimes and their effects on social and physical space. Advanced communications technology, rather than revealing itself to be a clean alternative for physical movement from place to place, seems to pave the way for an increase of physical and motorized mobility. The accelerating flows of data and commodities stand in sharp contrast to the elbowroom afforded to the biological body, which in fact is forced to a standstill. And while data, goods and capital have been freed of their territorial restrictions, the opposite is true for a growing portion of the world’s population: border regimes, surveillance and identity control are being intensified at a rapid pace. In short, on the one hand there is a question of an uncurbed and uncontrolled increase of mobility, while on the other, segregating filtrations are taking place.

Kluitenberg explores the contradictory regimes of (im)mobility in his introductory essay and searches for a perspective of intervention. He provisionally arrives at a ‘general economy’ of mobility, whereby the boundless longing for freedom of movement intensifies to the point of a ‘fatal worldwide standstill’. Following the example of Saskia Sassen, he concludes by turning to the local as a context from which effective counterforces can be generated on the global level. From another line of approach, namely the rhizomatics of Deleuze and Guattari, philosopher and jurist Marc Schuilenburg argues for connectivity with the local, introducing a new term in this regard: terroir, a contextualized approach to place and identity in which the emphasis lies on the dynamic relation between objects and people.

Charlotte Lebbe, architecture researcher, and Florian Schneider, media artist and filmmaker, each address the ambivalence of the present border regimes. Lebbe analyses how the external borders of the Schengen Area are being more and more strictly guarded with the help of new digital techniques, in order to regulate mobility. She sees the rise of a dispositif surveillance, the Ban-opticon. Schneider, seeking a new theory of borders and a different approach to mobility, argues in favour of abandoning the concept of the nation-state and advances the notion of ‘transnationality’. Architecture theorist Wim Nijenhuis presents a ‘dromological’ history of mobility, leading to the topical question of what exile means in today’s ‘exit city’.

Culture critic Brian Holmes examines the technological and cultural side of the capitalist mobility system: he analyses the intermodal distribution and transportation industry, in particular container shipping and the system of just-in-time production, drawing among other things upon Ursula Biemann’s video work Contained Mobility. Political sociologist Merijn Oudenampsen and architecture researcher Miguel Robles-Durán interviewed the social geographer David Harvey, who theorizes on the spatial effects of capital accumulation.

John Thackara, design critic, reflects upon the limitations of mobility as a challenge for designers, who ought to seek new ways of using space and time. Through a problematization of the mobility of food and its tracking, media theorist Tatiana Goryucheva investigates the preconditions for a democratic design of technology. Architect Nerea Calvillo expounds upon the project In the Air, which focuses on collecting data to visualize invisible elements in the urban atmosphere and aims at being a tool for increasing the awareness and participation of city inhabitants. The contribution by design and research collective Metahaven is about the mobility of money. In Mobile Money, they envisage new forms of money and capital.

Last but not least, in the column, media theorist Joss Hands, whose @ is for Activism: Dissent, Resistance and Rebellion in a Digital Culture recently appeared, discusses the mobilizing capacity of social media in the recent events in the Middle East, and how they can trespass on space, time, movement and personal will.

With Commonist Aesthetics, the editorial team Binna Choi (Casco), Sven Lütticken, Jorinde Seijdel (Open!) introduces “the idea of commonism” – not communism – as a topic that various writers and artists will explore and expand upon in the course of this series. Commonist aesthetics pertain to the world of the senses, or a “residually common world” that is continuously subject to new divisions, new appropriations, and attempts at reclamation and re-imagining.

The media through which news and information are gathered, produced and exchanged have expanded significantly over the last several years. Weblogs, advanced search engines, virtual environments like Second Life, phenomena such as MySpace, Hyves, Flickr and YouTube are offering new tools, communication options, social networks and platforms for public debate. These are micromedia or grassroots media: media that are largely programmed, supplied and broadcast by the user – in contrast to conventional macromedia such as television and the printed press, which are more institutionally determined. And these are ‘informal media’, used outside the formal protocols and authorized precepts of the old mass media, although, of course, various overlaps exist.

The rise of the informal media also implies the rise of the amateur, of the layperson or ‘citizen journalist’ making public pronouncements on all manner of social, cultural and political issues. Andrew Keen, in The Cult of the Amateur (2007), argues that the ascendance of the masses is a threat to the culture of authorities and experts, with mediocrity becoming the norm. He bemoans a lack of ‘gatekeepers’, who can determine the value of news and information on the internet. His critique allows no room for considerations of the emancipating, democratizing or subversive effect of the informal media.

Henry Jenkins, in his Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (2006), is more nuanced about the blurring of boundaries between media producer and media user, between the professional and the amateur – a process he calls ‘cultural convergence’. He emphasizes that this process is born out of the interaction between the commercial media industry and the user, out of negotiations between the consumer and the producer. The result is dynamic and capricious, has no clear outcome and is devoid of any set ideological programme. According to Jenkins, questions about the control of new internet platforms are particularly relevant.

In order not to be entirely lost or carried away in today’s public sphere, in order to be a political, social or cultural player, it seems essential to study the new instruments and platforms that function within that sphere critically. Open 13 features contributions by theorists and artists who reflect on the implications of the informal media for the public programme, conceived as the whole of public principles and requirements. Questions are raised about the conditions of our everyday media practices and about the opportunities for artists who work in a convergence culture.

Open 13 also includes specific attention to the changing position of conventional public media. Media scholar Oliver Marchart wonders how a radically democratic media policy can be conceived within the information society. The public dimension of television culture is also the focus of the special Hot Spot section compiled by Geert van de Wetering. Hot Spot, an initiative of the Dutch broadcasting organization VPRO, wants to investigate the implications and possibilities of the shifts in media production, distribution and consumption. How might programme makers benefit from an audience that participates in conceptualization and discussion?

Media philosopher Martijn de Waal assesses the democratic quotient of processes of valorization and systems of collective intelligence within the public sphere of Web 2.0. Internet critic Geert Lovink delves specifically on the expanding ‘blogosphere’. He sees blogging as a nihilist enterprise that undermines traditional mass media without stepping forward as an alternative. Henry Jenkins’ ‘Nine Propositions Towards a Cultural Theory of YouTube’ are included in the column. Media theorist Richard Grusin looks at the commotion around the Abu Ghraib photographs in light of our everyday media practices. Art theorist Willem van Weelden interviews web epistemologist Richard Rogers on the politics of information and the web as a discrete knowledge culture. Web sociologist Albert Benschop compares the 3D structure of Second Life with the old, ‘flat’ web in relation to such aspects as methods of communication and the creation of power. DogTime students Arjan van Amsterdam and Sander Veenhof made a visual contribution. Artist and media researcher David Garcia sees, precisely within a commercial service industry in which media are omnipresent, opportunities for artists to contribute critical services and effective tools.

Artist Florian Göttke created a visual contribution derived from his project Toppled, an archive of news and amateur photographs taken from the internet, documenting the toppling of the statues of Saddam Hussein. I have written a text about iconoclasm and iconolatry and the potential of Toppled as a shadow archive. Felix Janssens and Kirsten Algera, of the design and communications agency Team TCHM and the makers of PRaudioGuide, produced the contribution Hollow Model, a number of templates with text in which they interrogate ‘the public of the public’ and the role that media and media use play in this. Is the public made hollow if it exists only in the media?

This Open reflects on old and new forms of social engineering in relation to the urban and social space as well as to (communal) life within it. Is social engineering now a hollow ideal, or does it offer new, urgent perspectives?

Social engineering, in an objective sense, only refers to an analysis of the possibilities of constructing something. In relation to, for instance, sociopolitical reality, a strong faith in social engineering was an element of the utopias and idealized societies of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the course of the last century, however, social engineering also became a more specific, almost self-sufficient concept. As part of the modernist concept and as an expression of an optimistic faith in progress, there emerged, particularly in the Netherlands, an explicit discourse of social engineering1 dealing with societal models to be realized (the welfare state) or forms of citizenship to be stimulated (the emancipated citizen), which were also mirrored by large-scale physical social engineering projects. As part of the modernist projects in the domain of urban design (the Bijlmermeer) and spatial planning (the impoldering of the Zuiderzee, the Delta Plan), social engineering also became a more specific, almost self-sufficient concept. Social engineering became associated with a social-democratically oriented faith in government intervention and with a belief in a nature that could be controlled by man.

Over the last several decades, there as been an apparent abandonment of social engineering and its ideals. Cultural critics such as John Gray attacked the general faith in social engineering and progress as a disastrous regression to the utopias of the Enlightenment, degenerating into a destruction of culture and nature and providing fodder for totalitarian thinking. At the same time, affluent Western countries experienced the bankruptcy of the welfare state, and developments such as privatization, globalization, migration, international terrorism and climate change generated steadily increasing scepticism about the social engineering of the world. In neo-capitalist postmodernity, or as culture philosopher René Boomkens called it, 'the new disorder', social engineering seemed a phantasm.

The question is, however, whether the philosophy of social engineering had really disappeared or whether it is being used by neoliberal philosophy, using the procedures and instruments of the market and corporate management and targeting the individual. The model of the 'creative city', in which creativity and entrepreneurship are implanted in the urban fabric, seems a quintessential product of this 'neo-social engineering'. Other 'neo'- social engineering models might be the network society, the information society, the knowledge society, and of course the security state. Neo-social engineering, after all, seems to tap the logic of the police and the secret services as well: the security state is emerging as the most current and complex societal ideal of the moment, dystopian and disturbing as it may be considered from the standpoint of the old philosophy of social engineering, yet at the same time based on the utopian desire that liberty and security might be compatible – a desire that is also part of the neoconservative ideology of the Americans, which illustrates, as John Gray emphasized, the current right-wing philosophy of social engineering.

And then there is that other current obsession in which a belief in social engineering plays a role, namely 'the citizen': according to the Dutch 'Assimilation Delta Plan', a demonstration of contemporary biopower, legal newcomers from outside the European Union are transformed into national citizens, while the European Commission programme 'Citizens for Europe' wants to turn national citizens into European citizens. And all these citizens have to be 'active' citizens – illegals and refugees excepted.

Philosopher Lieven De Cauter, in his book The Capsular Civilization, emphasizes the impossibility of a non-social engineered society: 'It is not because total social engineering is dangerous that society should not be engineered, albeit relatively engineered. If society were not engineerable, it would be a natural process, or an accidental coincidence, or destiny. No politics can be conducted on this basis, and there is not a single historian who cannot demonstrate that society is engineered, not created, and moreover by a complex process of decisions.' De Cauter indicates that he believes in the countering force of a relative social engineering, thereby touching on current discussions about urban politics and social systems, in which theorists and designers are again asking whether social engineering is not a requirement of the human longing for organizational forms and intervention that vouchsafe a pleasant communal life. In its contribution, BAVO rightly asks to what extent relative social engineering can lead to an actual repoliticization and not remain mired in an ethical appeal without consequence. Are there new, emancipatory forms of a philosophy of social engineering, in which agency is pre-eminent, that might provide a tactical, political or activist response to dominant neoliberal and neoconservative tendencies?

For a long time, the public sphere as a space in which rational debates are conducted, free of prescriptive forces, and public space as a common world were guiding concepts in the discourse on publicness defined by such thinkers as Jürgen Habermas and Hannah Arendt. These enlightened forms of ‘civilized publicness’ seem far removed from either the theory or the practice of the present day. Neoliberal forces, such as privatization and commercialization, are torpedoing the idealized modern concepts of the public sphere, which is being increasingly defined, in terms of a practical project, by acute expectations concerning security and threat. At the same time, public space is being claimed by groups and audiences such as illegal aliens, refugees and migrants, who are not accounted for, or only minimally, in official policy dealing with this space.

Indeed, current thinking about the public sphere and publicness is no longer based on models of harmony in which consensus predominates. Repeated references are made to Jacques Ranci¯re or Chantal Mouffe, who emphasize the political dimension of public space and its fragmentation into different spaces, audiences and spheres and in whose view forms of conflict, dissensus, differences of opinion or ‘agonism’ are in fact constructive and do justice to many. This means public space has once more become an urgent topic in the debate on liberal democracy, a debate which, supported by radical-leftist philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben or Alain Badiou, is increasingly focusing on the relationship between politics and life, in which ‘the political’ often runs counter to politics itself.

In the wake of these developments, the artistic space of art and its institutions is also repeatedly considered as a social or even political space, as a public issue. The aesthetic and the political are played off against each other, and new questions are being formulated about autonomy and serviceability. This issue of Open examines how art and its institutions are reinventing, reformulating or re-legitimizing their public dimension and involvement. A neutral position, after all, seems at the very least naïve here: both art and art institutions still manifest themselves at the sufferance of the public, the audience. They cannot avoid re-examining what is public (or not) and why, who the audience is and how they want to relate to it. Do they dare become part of ‘the political’, or do they let themselves become instruments of market players and party politics?

Chantal Mouffe postulates her ‘agonist’ model of space and the role she sees for the artist within it. Nina Möntmann outlines how small art institutions can play the role of the ‘wild child’ and adopt a meaningful (counter)position in public space. Simon Sheikh observes that the erosion of the nation-state has produced a post-public situation, in which the public sphere or ‘the public’ can no longer be precisely localized.

The controversy sparked in Germany by Gerhard Richter’s stained-glass windows for Cologne Cathedral inspires Sven Lütticken to reflect on the cathedral, the museum and the mosque as public space. Sjoerd van Tuinen argues for a Sloterdijk-esque perspective on the public sphere, in which the intimate is taken seriously and art actualizes concrete forms of ‘conviviality’. Artists Bik Van der Pol have produced a contribution about a spot in the Park of Friendship in Belgrade that was once the planned site of the Museum of Revolution.

Jan Verwoert rejects the idea that artists and exhibition makers should be required to identify their audience. To him, this reeks of an economic legitimization of culture, and he sees anonymity, on the contrary, as a pre-requisite to meaningful encounters in the cultural domain. In its column, 16Beaver denounces the reduction of the world, of art and of its institutions to numbers, because ‘the stakes are immeasurable’. BAVO calls on artists to link radical artistic activism with radical political activism.

As curator of the Dutch pavilion at the last Venice Biennale, Maria Hlavajova, artistic director of BAK in Utrecht, worked with Aernout Mik, who produced the video installation Citizens and Subjects. This led her to consider the relationship between art and society, as well as such concepts as community and nationalism. Florian Waldvogel questions Kasper König about his experiences with ‘Skulptur Projekte Münster’, which König organized from 1977 to 2007, and in the process outlines the evolution of the relationship between art, public space and the urban environment. Max Bruinsma spoke with Jeroen Boomgaard, professor of Art in the Public Space at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, and Tom van Gestel, artistic director of SKOR, about the role of art in a public space where public-private partnerships dominate and where public interests are mixed with economic and managerial interests.

Camiel van Winkel De mythe van het kunstenaarschap, Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam, 2007, isbn 9789076936192, 96 pages

With the international credit crisis there is more and more talk of the crumbling of the neoliberal hegemony. Whatever this may mean exactly, in relation to the theory and practice of art and public space this very crumbling also seems to be revealing implications and effects of neoliberalism that were previously suppressed, at least in mainstream discourse. Assuming that neoliberalism, consciously or unconsciously, is more or less internalized in the policy and programmes of art and public space, a crisis of market thinking is also affecting the core of these domains. In other words, if neoliberalism fails economically, socially and politically, what are the symptoms of this within art and public space? And how should we be dealing with this?

Two concepts resonate in this issue of Open – ‘post-Fordism’ and ‘precarity’ – the first being something that can be called a manifestation of neoliberalism and the second an effect. The premise is that post-Fordist society has supplanted the Fordist order: the hierarchical and bureaucratic production system as worked out by Henry Ford and Frederick Taylor is no longer dominant. This system was characterized by the mass production of homogeneous, standardized goods for a mass market. Since the 1970s, however, there has been a shift of emphasis within the organization of labour to the immaterial production of information and services and to continuous flexibility. Both systems reflect different social and economic value systems – the mainstays of post-Fordism are physical and mental mobility, creativity, labour as potential, communication, virtuosity and opportunism – and have their own forms of control

The political philosopher Paolo Virno sees a direct connection between post-Fordism and precarity, which refers to the relationship between temporary and flexible labour arrangements and a ‘precarious’ existence – an everyday life without predictability and security – which is determining the living conditions of ever larger groups in society (part-timers, flex workers, migrant workers, contract workers, black-economy workers, etcetera). This structural discontinuity and permanent fragility also occurs in the ‘creative class’: art, cultural and communication businesses in which there is talk of flexible production and outsourcing of work. Through the agency of European social movements and activists, and philosophers such as Virno, precarity has been a political issue for some years already in countries like Spain, France and Italy.

Brian Holmes writes in this issue about the video series Entre Sueños, in which artist Marcelo Expósito reports on this ‘new social issue’. Merijn Oudenampsen deals very concretely with the response of Dutch cleaners to their precarious situation. Brett Neilson and Ned Rossiter contend that the rise of precarity as an object of academic analysis coincides with its decline as a political concept capable of inciting social action. They sound out the power of precarity to bring about new forms of connection, subjectivity and political organization. Gerald Raunig poses the question as to whether the post-industrial addiction to acceleration can create strategies that give new meaning to communication and connectivity.

What can notions like post-Fordism and precarity bring to light when they are related to the current conditions of, and thinking about, urban space and about art and the art world? In the context of the city, the ‘creative city’ thrusts itself forward as a post-Fordist urban model par excellence, whereby creativity and culture are seen as the motor for economic development. The creative city is also an entrepreneurial city in which city marketing and processes of gentrification go hand in hand, and in which social issues are subordinated to the demands of the labour market and the production of value. Matteo Pasquinelli, in particular, directly addresses the role played by the creative scene in making (im)material infrastructures financially profitable and susceptible to speculation. The architect and activist Santiago Cirugeda has made a poster with a selection of urban interventions created in recent years by his office Recetas Urbanas, which are aimed at regaining public space for citizens within the precarity of the urban environment.

Nicolas Bourriaud argues that the essential content of contemporary art’s political programme is not an indictment of the ‘political’ circumstances inherent to current affairs, but should consist in ‘maintaining the world in a precarious situation’. Sonja Lavaert and Pascal Gielen interviewed Paolo Virno in Rome about such matters as aesthetics and social struggle, the disproportion of art and the need to invent institutions for a new public sphere. Gielen describes in another article how the international art scene embodies and indulges the post-Fordist value system, and asks to what extent its informality and ethics of freedom can be exploited and managed biopolitically. From the heart of the art scene Jan Verwoert resists the imperative to perform creatively and socially, and calls for a different ethics, one that all of us should be able to take to heart.

Open 9 examines the role of sound in the public domain. After all, public space is manifest not only visually, but also, and to a considerable extent, acoustically: its public nature hinges on visibility as well as on audibility. All the same, the accent in cultural or social analyses of the public space still often rests on the visual. Despite sound’s ubiquity and inescapability, it is usually regarded as being merely illustrative, a minor consideration or nuisance. Marshall McLuhan took a critical stance on the dominance of ‘visual space’ as the ‘linear, quantitative mode of perception that is characteristic of the Western world’. In his view, however, this traditional space was being superseded by the ‘global village’, constituted by the electronic media, which he likened to ‘acoustic space’, a mythical, tactile, organic and integral space that is characterized by solidarity.

Though this now seems largely utopian, it is clear that technology and new media amplify the auditory space, or add an extra dimension that has aesthetic, ethical and political implications. For this reason alone, involving the role of sound in reflections on public space and in its design is as necessary as taking the visual into account. In recent years there seems to have been an increasing sensitization for the auditory aspects of everyday life and the public domain. Within ‘cultural studies’, ‘sound studies’ has emerged as a serious area of research that focuses on the history of audio media, on reflection about the nature of sound and listening or on the role of sound in modern experience and perception. In the visual arts, research is focused on the potency of sound as an aesthetic, meaningful or communicative element in relation to social or spatial environments. The medium of radio, which has proven itself capable of embracing digital culture, seems to be undergoing a veritable cultural revival, and is also being extensively explored artistically.

In Open 9 there are essays about the way in which sound and audio media play a role in urban public environments, and how they can propagate publicness or indeed sabotage it. Jonathan Sterne, whose published work includes The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction (2002), underscores how ‘acoustic design’ or ‘sonic architecture’ can be deployed as a tactical instrument in the politics and design of urban culture in order to manage spaces. In their ‘pop analysis of the urbanization process’, Alex de Jong and Marc Schuilenburg were inspired by Peter Sloterdijk’s ‘spheres’ concept. Using techno, the architecture of Archigram and ‘Urban’ youth culture as examples, they argue that spheres lead to a shared urban experience. Within the specific context of the city, Caroline Bassett examines the qualities of the auditory space created by mobile telephony, which make possible a new, mobile subjectivity. In the literary essay ‘The Multiplication of the Street’, Dirk van Weelden writes about the changing relations between radio and publicness based on his fascination for the physical aspect of listening to radio. In the column ‘Listen and Learn’, Siebe Thissen calls into question the protection of copyright by the music industry with respect to ‘audio bloggers’ on the Internet.

Open 9 also features a range of international artists from different generations. They explore the possibilities and conditions for sound and public space in their work, as well as the limitations. Based on an interview, Brigitte van der Sande discusses the work of Moniek Toebosch, a performance and audio artist in whose work sound has played a critical role from the very start. Ulrich Loock analyses Max Neuhaus’s sound artwork Times Square, which was installed invisibly on Broadway in New York City in 1977. Artist Mark Bain discusses his critical intercourse with sound and space in a text about repressive and subversive sonic techniques. For a performance at the Kalvertoren shopping centre in Amsterdam, the German collective LIGNA wrote an evocative ‘monologue for a broadcaster’s voice’ about the future of radio art. Jeanne van Heeswijk and Amy Plant designed a new sound medium, the Vibe Detector, as a means to gain an understanding of urban transformation processes. The device was tested in a neighbourhood in London. A series of logbook fragments that sprang from this, as well as documentary photos, illustrate how ‘fleeting layers of sound’ can reveal what is happening in a specific area.

As a supplement to Open 9 there is an mp3 disc that includes work by Toebosch, Bain and LIGNA. Besides the audio version of the above-mentioned monologue by LIGNA, Dial the Signals! , a radio concert for 144 mobile telephones, is also included. The disc also includes a special compilation of radio programmes that were made in autumn 2005 and broadcast during Radiodays, a project by participants in the 10th Curatorial Training Programme at De Appel in Amsterdam. One of the curators, Huib Haye van der Werf, made an audio selection including interviews with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Suchan Kinoshita along with programmes by Raul Keller, Guy van Belle and James Beckett for Open 9.

Read and listen!

The philosopher Hannah Arendt defined public space as a place where people act to create a ‘communal world full of differences’. But where does this space manifest itself today, that generally accessible domain where people meet one another and create public opinion and hence a form of political practice? In physical places like streets, squares and parks? In mass media such as newspapers and television? Or on the Internet, in chat rooms and newsgroups? Publicness is increasingly enacted in all these places simultaneously and in that sense has become supremely ‘hybrid’ in nature: a complex of concrete and virtual qualities, of static and mobile domains, of public and private spheres, of global and local interests.

The configuration of hybrid space is currently experiencing a powerful impetus thanks to wireless and mobile technologies like GSM, GPS, Wi-Fi and RFID, which are making not only the physical and the virtual but also the private and the public run into each other more and more. And although we apparently deal with this flexibly in our daily lives, what is often left aside in debates on environmental planning or on social cohesion, or in cultural analyses, is the fact that the use of these wireless media is changing the constitution of public space. They can be deployed as new mechanisms of control, but also as alternative tools for enlarging and intensifying public activities – whether it’s a matter of parties, events or meetings, or of campaigns, riots and demonstrations. Wireless media make a ‘mobilization’ of public space possible, both literally and figuratively, so that it is no longer static and can be deployed by individuals or groups in new ways. Open 11 deals specifically with the implications that these mobile media have for public activities, and hence with the public dimensions of hybrid space. The issue has been produced in collaboration with guest editor Eric Kluitenberg, theorist, writer and organizer in the field of culture and technology. In his introductory essay he asks himself how a critical position is possible in a hybrid space that is characterized by invisible information technology. Together with Howard Rheingold, author of the renowned book Smart Mobs: The Next Social Revolution (2002), Kluitenberg has also written a polemical piece about the right and the ability to ‘disconnect’, that is to say, about not being connected with the ‘network of waves’ as a form of acting.

New wireless, mobile media and hybrid space are being used experimentally and reflected upon on a small scale by a select company of artists, designers, architects and urban designers. In her essay for Open, the sociologist and economist Saskia Sassen looks at ways that artistic practices can ‘create’ a type of public space within globalized network cities that can make visible the local and the silenced.

On the basis of their projects for the Ruhr region in Germany, architects Frans Vogelaar and Elisabeth Sikiaridi provide an account in Soft Urbanism of how urbanism and architecture can be combined with information and communication networks. The researchers of the design project Logo Parc critically analyse the ‘post-public’, hybrid South Axis area of Amsterdam and make proposals for experimental design strategies.

Assia Kraan writes about how ‘locative arts’ – art that makes use of location- and time-conscious media like GPS – can stimulate public acting in urban spaces. The Droombeek locative media project is discussed separately by Arie Altena. Max Bruinsma analyses OptionalTime by Susann Lekås and Joes Koppers. Klaas Kuitenbrouwer looks at the cultural and social possibilities of RFID. The artists / designers Kristina Andersen and Joanna Berzowska discuss the social possibilities of wearable technology in clothing.

Noortje Marres’s column reflects on the public’s (in)ability to act and the role the media plays in this. The German researcher Marion Hamm reports on the Critical Mass bicycle tour in London in 2005, a political demonstration against neoliberal globalization, which was experienced and prepared as much on the Internet, particularly by Indymedia, as in physical space.

The interview by Koen Brams and Dirk Pültau with the Flemish television maker Jef Cornelis is part of a larger research project at the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht about his work and also provides the theme of Open 11 with a historical dimension. The conversation deals with the conditions of TV as a public medium and the changes in urban public space that Cornelis drew attention to in his early films such as Mens en Agglomeratie (1966) and De Straat (1972).

This issue of Open includes the CD-Rom Amsterdam REALTIME. Dagboek in sporen / Diary in Traces, a GPS project by the artist Esther Polak in collaboration with Jeroen Kee and the Waag Society. Made in 2002, it deals with mobility and space and has in the meantime become a classic point of reference within ‘locative arts’.

On the invitation of Open, the design and art collective De Geuzen has contributed Mobiel Werk, which is partly concealed in the cover.

No discourse seems more hollow at the present moment than that about tolerance and freedom of expression: in Western culture, and not least the Dutch, enlightened ideas are scarcely capable any longer of generating meanings that apply and appeal to all of us. Through all political groupings, controversies great and small are wreaking havoc on democracy’s traditional consensus model and cutting across the public domain. The formal and informal codes, rules, agreements and symbols that determine our freedoms and rights within that domain have ceased to function effectively. One would be tempted to call some of the results cartoonish, were it not for the fact that they have entailed so many real deaths.

Leaving cynicism and nihilism behind, the politico-philosophical concept of the public sphere needs to be articulated anew. The desire for this is projected not just onto politics, but also onto art as the most obvious domain of freedom of expression and symbol formation. Architecture and the city also present themselves as projection screens for experimental ideas about the communal, the heterogeneous and the autonomous.

Open 10 brings together analyses, stances and proposals of theoreticians, artists and designers who examine questions concerning contemporary symbolism and freedom of expression, artistic and otherwise, in relation to the Western notion of tolerance and forms of extremism. The failure of consensus thinking and acting finds expression at various levels. It is no accident that the ideas of philosopher Jacques Rancière – author of The Politics of Aesthetic: The Distribution of the Sensible (2004) – concerning the possibilities of a political aesthetic and the perspective of the ‘dissensus’ are cited with increasing frequency in cultural and art theory discourse. Ranci¯re argues that a true democracy should be founded on a productive ‘dissensus’, whereby two worlds are located within one and the same world. The radical nature of this proposition appears more stimulating in the present situation than the whiny and exhausted harmony model.

The ‘dissensus’ possibility does not exclude an appeal to idealism and engagement. In his Atmosphere trilogy, Peter Sloterdijk describes how the macro-atmospheres (‘Globes’), homogeneous spaces where everyone is equal and secure, are ‘frothing away’ to nothing. Modern pluralism and individualism give rise to an infinity of foam bubbles, to micro-atmospheres (‘Bubbles’) that are both connected to and separated from one another. Sloterdijk believes in the positive power of such foam and argues that we must learn to think ‘inside out’ in order to be able to deal with the increasingly blurred distinction between inside and outside.

In the essay ‘Citizens in a Vat of Dye’ Sloterdijk examines the premises for a democratic society and the importance to it of written and representational media. The roots of democracy also feature in Tom McCarthy’s interview with architect Maurice Nio and artist Paul Perry about their Amsterdam 2.0 project, which provides a constitutional framework that allows 400 cities to inhabit the same territory and which is based on a system of ‘radical tolerance’ whereby the citizens of one city are constitutionally prevented from imposing their will on the others.

In their open letter, Lonnie van Brummelen and Siebren de Haan emphasize the importance of a ‘reflective interchange’ between the institutional interior of art and the ‘exterior’ where it is installed. Open also includes textual and visual excerpts from Van Brummelen’s publication The Formal Trajectory which recounts the long application process that preceded her Grossraum film project.