A Rehearsal of Inadequate Performances

The political trial as a cultural artifact

November 14, 2014essay,

Iratxe Jaio and Klaas van Gorkum’s experiences during the making of the video Últimas Palabras in Argentina in 2013 have allowed them to reflect on the historical and didactic nature of the political trial. The video – published at the bottom of this text – focuses on the trial and closing argument of ex-Naval Commander Alfredo Astiz (aka “The Blond Angel of Death” during Jorge Rafael Videla’s dictatorship). It is presented here as a case study that demonstrates how Astiz’s final plea can be read as an expression of power relations in society.

“Proceed”, said the newly elected president of Argentina, Néstor Kirchner. It was the 24th of March 2004, and an audience of ministers, high-ranking military officers and journalists watched a man in uniform step forward onto a small ladder, propped against the wall of the gallery in the Military Academy. Cameras flashed, as he took down the stately portraits of General Videla and General Bignone, almost 20 years after the fall of their violent regime. It was a powerful, symbolic gesture that indicated a clean break with those institutions and policies that had failed to address the lingering legacy of the military junta.

Just a couple of years earlier, at the peak of the economic crisis in Argentina, the streets were filled with people shouting “Que se vayan todos!” (“They all must go!”). People were banging pots and pans and burning down the banks, and they managed to topple four presidents in less than three weeks. Popular power was reconstituting itself outside of traditional party politics in the form of neighbourhood assemblies, arts collectives, bartering clubs and occupied factories.

Kirchner had been elected with a bare twenty-two percent of the votes and faced the task of recuperating the state’s lost credibility. By taking down these photos, he demonstrated that he was willing to dismantle the establishment and take on the powerful actors who controlled it from behind the scenes. Before his first term as president was over he had purged the armed forces and the police, impeached judges from the Supreme Court on charges of corruption and repealed the two infamous amnesty laws that had protected the perpetrators of human rights abuses during the dictatorship.

A historical process had been set in motion. But to fully understand the instrumentality of this moment would be like removing the front of a clock to reveal an obscure mechanism of contradictory movements behind the straightforward logic of the turning hands. Everything is connected but each turn of the interlocking cogs only appears to result in the rotation of another one in the opposite direction.

It would take a few more years before Alfredo Astiz finally stood before the court in Argentina to hear the judge sentence him to life imprisonment for crimes against humanity. Known as the “Blond Angel of Death”, this ex-Naval Commander had participated in the kidnapping, torture and disappearance of those who resisted the military regime’s dictatorial rule and in the death flights and crimes committed at the notorious School of Naval Mechanics. His trial put an end to the years of impunity he had enjoyed under the old amnesty laws.

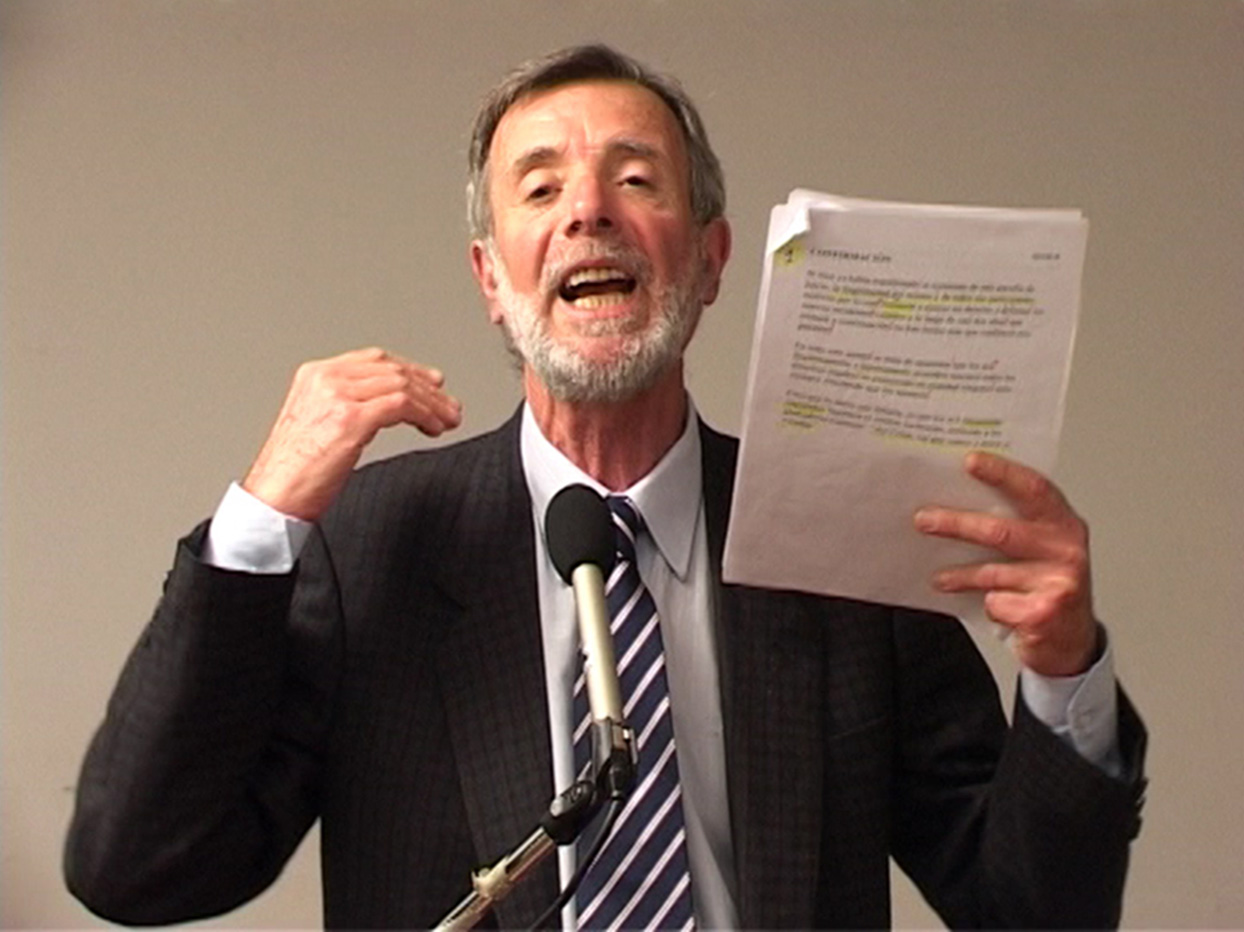

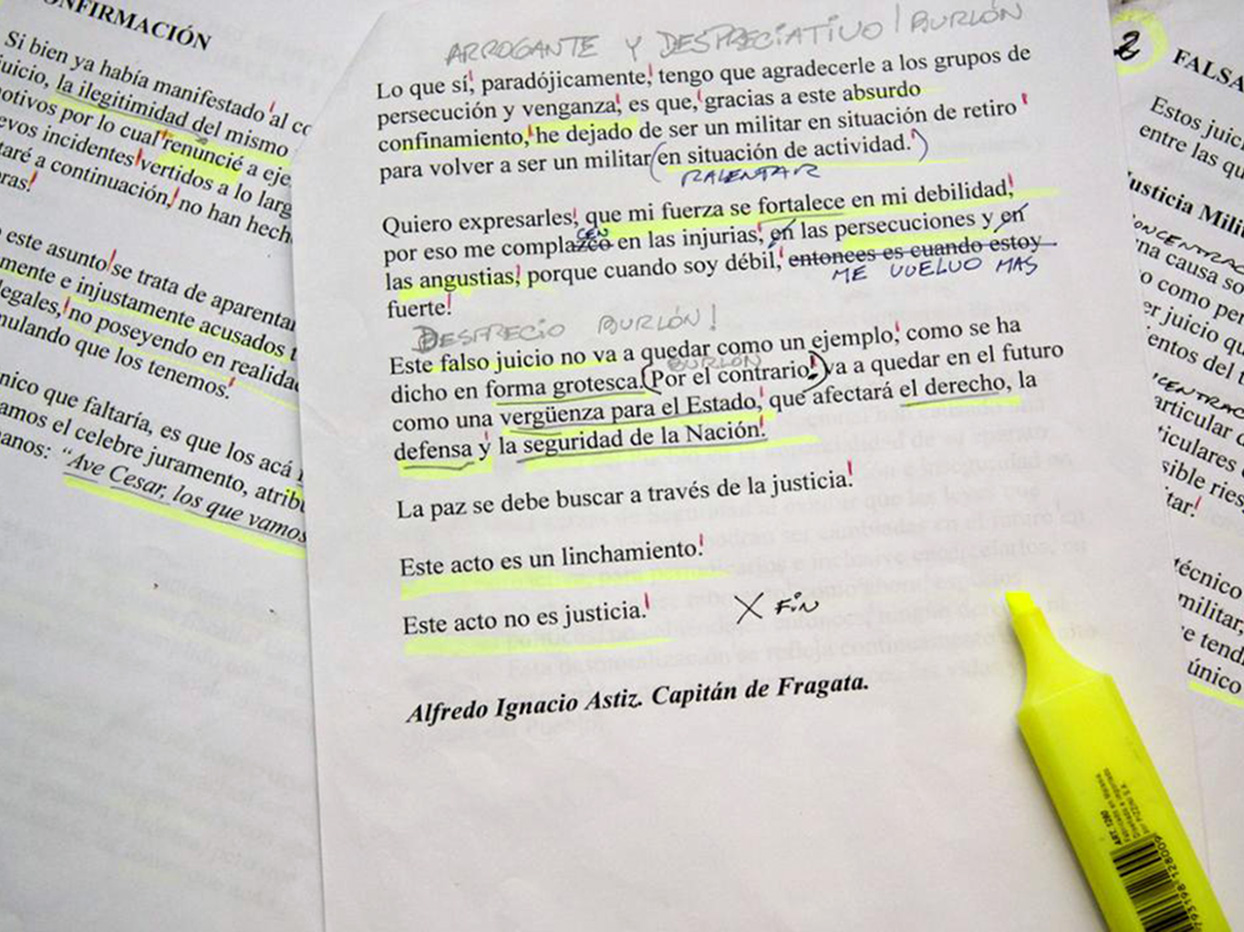

In his closing statement, a bitter speech that took hours to complete, Astiz showed no intention of either apologising for his crimes or proving his innocence. In a theatrical attempt to reverse the situation, he disputed the legitimacy of his prosecutors and described himself as a military hero who had been persecuted merely for following orders. With an ominous appeal to history, he cautioned his judges of the judgment that would befall them in the future and then denounced the proceedings as a political show trial.

Jacques Vergès, a French lawyer who became notorious for defending so-called terrorists and war criminals, would have identified this approach as a “defense de rupture”. This was his central tenet in his 1987 legal defense of Klaus Barbie, an old Nazi who had been put on trial for crimes including torture and killing that he committed as a member of the Gestapo in Lyon. Rather than try to prove Barbie’s innocence or seek a reduced sentence, Vergès’ courtroom strategy consisted of challenging the legality and morality of the state that had built the case against him.

His approach could be regarded as a form of immanent critique in the sense that it wasn’t formulated from an externally normative position. By accepting the law’s claims to objectivity, neutrality and universality, the lawyer was aiming for a collapse of the institutional framework under the pressure of its own moral principles, by relentlessly exposing its contradictions and by revealing the hypocrisy from within. In dramatic speeches addressed to both the court and the media, Vergès consistently shifted the attention towards the collaboration of the French themselves in helping to implement the Final Solution, as well as their own brutal legacy of torture and counter-terrorism during the Algerian war.

This strategy, however, did not succeed in exonerating his client who was sentenced to life imprisonment. But it did successfully disrupt the trial’s dominant narrative, which many expected would be a triumph for the prosecution and a tribute to the suffering and heroic resistance of the French under the Nazi occupation. With his indictment of Western imperialism, Jacques Vergès had managed to reconfigure the historical and didactic nature of the trial, and, as a result, was able to force the French into confronting a part of their past that had up until that time been repressed.

The lawyer often compared the justice system to theatre. He understood that there was a performative logic to the nature of law, which was the result of the fundamental indeterminacy of legal discourses. It allowed him to transform a political trial from a mere instrument of power into a cultural artefact that was capable of provoking a public reflection on hegemonic norms and transforming the law itself. “A trial is a place of metamorphosis,” he was known to say, “Joan of Arc wouldn’t have been a saint without her trial.”

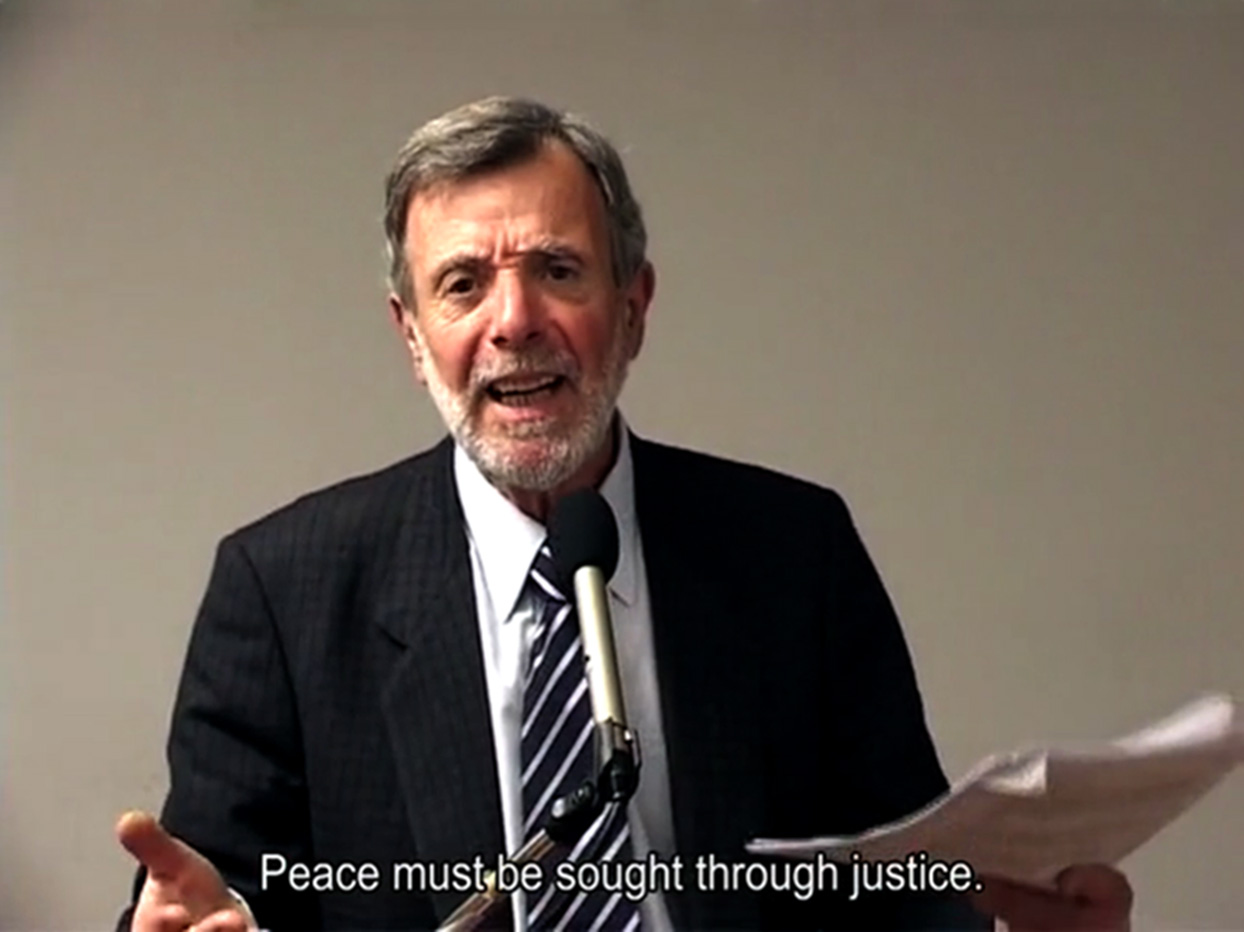

In 2013, we received a Dutch grant for the artists-in-residence program at the LIPAC, the Laboratory of Investigation into Contemporary Art, in Buenos Aires. During our research into Argentina’s recent history, we came across a copy of Astiz’s final speech at his trial and decided to use it in a kind of forensic experiment. We hired an actor and asked him to play the part of Astiz by sitting him in front of a camera and asking him to read the transcript aloud. A speech instructor guided him through the text and encouraged him to attain its full rhetorical breadth. The actor was not given the opportunity to read the speech beforehand and the instructor was rigorous and unsparing with his pupil. A fascinating power game developed between the two men as the actor grew into the imposing character we had asked him to play.

The resulting video Últimas Palabras should be seen as a case study demonstrating how Alfredo Astiz’s discourse can be read as an expression of power relations in society. It neither attempts to resolve the antithetical relation between the ex-commander and the constitutional democracy in which he was convicted, nor does it present its audience with an unambiguous moral standpoint. It is up to the viewers themselves to work their way through the work’s internal contradictions, essentially turning every screening into a performative iteration of the ceremony of judgment.

Of course, there is a certain predisposition to read the work as critique when it is shown within the consecrated walls of cultural and academic institutions. But how would, for example, a viewer who sympathises with the former military regime view the video? Could it be interpreted as a vindication of Alfredo Astiz and be co-opted by a reactionary political agenda?

An opportunity to put this to the test was provided, unexpectedly, by the Dutch ambassador, right before we left Argentina. Having heard of the video’s success at the premiere, he had summoned us to present it to the embassy’s staff and guests. Diplomats, secretarial staff, and a number of gentlemen in impeccable suits (bankers and corporate executives, the captains of industry) were all convened around a table.

Among the heads turned attentively towards the screen, there was one of an Argentine man who early on could be seen nodding enthusiastically with the line of argument of the actor-defendant’s speech. But eventually his face darkened and, as the final credits appeared, he could no longer contain his indignation.

The man worked at the consular department of the embassy and was a former Army officer, he would have us know, and a personal friend of the Astiz family. He had closely followed the actual court case with his former colleagues. He pointed angrily at the screen and said that he might as well have been the one on trial back then. If he had received the order to infiltrate the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo instead of Astiz, he would have complied immediately, without hesitation.

The diplomats and executives sitting around the table played dumb, but they must have known how, in 1977, Astiz had passed himself off as a victim of the repression in order to gain access to the human rights organisation. Shortly thereafter, twelve members of the organisation, including its founders, were kidnapped and never seen alive again.

This former Army man then went on to declare that he felt violated by the video. He was offended by the irreverence with which the speech instructor provoked the actor to “overact” his part. He felt that the performance was inadequate because it failed to capture the dignified composure with which Astiz, a man of discipline and military honour, would have pled his case. He then started fulminating against foreign interference in domestic affairs, referring to the French who had initiated the case against Astiz and, in striking imitation of Vergès’s rupture defense, invoked their conduct during the Algerian war.

At this point, however, he was cut short by one of the Dutch gentlemen, who, with an air of condescending paternalism, announced that the video should not be shown in Argentina again because the people were simply not ready for it. The ambassador then began to inquire about who had funded our stay in Buenos Aires and whether they were aware of what we were doing. The meeting ended and our audience hurried back to their offices. On the way out, the man who had advised against further screenings asked us whether we were afraid we might be detained at Schiphol airport back in the Netherlands for having this video in our possession.

We guessed he meant it as a joke, although a rather unsavoury one in light of the recent discovery of the blacklists of artists and intellectuals that the military regime had collected, classifying them based on their perceived threat to the state on a scale from F1 to F4. What this episode at the embassy taught us is that, even in the so-called enlightened Western democracies, values such as civil liberty and political freedom aren’t written in stone but are constantly subject to various opposing interests.

On 30 April 2013, a day before we flew to Argentina, thousands of people dressed in Dutch royal orange filled Dam Square in front of the palace in Amsterdam. They were waiting for a glimpse of their new king, who was to be crowned that day. The few lone protesters who had been holding cardboard signs declaring their opposition to the monarchy had by then already been removed by the police, only to be released a few hours later, after the festivities, with the excuse that they had been arrested due to a “misunderstanding” in the chain of command.

A loud cheer went up in the square when the monarch finally stepped out onto the balcony. Flanked by his wife, Máxima Zorreguieta, and his three daughters, the new king of the Netherlands gazed out over the gilded balustrade, and waved at the enraptured crowd below. The controversy over his marriage to an Argentine investment banker, the daughter of a man who had served as a minister under Videla, seemed but a distant memory. The public prosecutor’s office in the Netherlands had already announced that it was unlikely to follow up on the charges that had been brought against Jorge Zorreguieta by two Dutch lawyers on behalf of relatives of those who had been forcibly disappeared from his department during the regime.

By the time our plane landed on Dutch soil three months later, Máxima had settled into her role as a public figure. Art institutions who have all seen their budgets cut by the right-wing coalition government are hoping to take advantage of her unprecedented popularity by inviting her to open exhibitions and award prizes, hoping that this will turn her into a patron of the arts. The Royal House has, meanwhile, commissioned the organisation that funded our trip to Argentina to select artists to create the official portraits of King Willem Alexander. At what cost, we wonder, as we wait in the arrivals hall, listening to the rattling sounds of the luggage carousel, hoping that it will bring us our suitcases from behind the scenes.

Iratxe Jaio & Klaas van Gorkum are artists. They have worked together since 2001, producing performances, videos, publications and installations. Using documentation as their work methodology, they analyse and question social and political issues concerning the everyday. Their work is often said to be political, as it brings to the surface contradictions and conflicts that may exist between individual and collective experience. In 2010 they wrote a monthly article reflecting on the relationship between art and politics for Mugalari, the cultural supplement of the Basque newspaper Gara. A selection of these texts can be read online at www.postpolitikak.org.