Acting in the Real

November 1, 2005review,

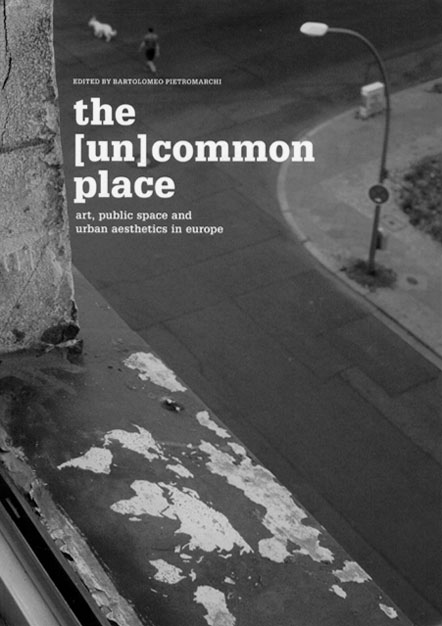

Bartolomeo Pietromarchi (ed.), The [Un]Common Place. Art, Public Space and Urban Aesthetics in Europe, Fondazione Adriano Olivetti and Actar, 2005, ISBN 8495951983

This book is the result of Trans: it. Moving Culture through Europe, a research project focused on ‘creative practices between art, architecture and urban research that are redefining the concept of public space’ that took place in Europe over the last three years. The book documents more than 50 projects and includes three documentaries on dvd. Trans: it also counts the exhibition ‘NowHere Europe’ – recently presented in Venice – and the website www.transiteurope.org among its instruments. Related presentations and workshops have also been held, for example ‘Social Actors in Transformation (sait)’ at the Witte de With Centre for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam.

The intention of Trans: it as a whole was to establish an international platform for research, documentation, debate, analysis and reflection relating to recent ‘artistic experiences’ in European public space. In his introduction to the book, Bartolomeo Pietromarchi calls for a debate about the public space in present-day Europe, a public space that is in flux and in places has degenerated into an ‘object of merchandising’. Before all meaning is lost, The [Un]Common Place wants to render more accessible the notions of public space and public domain as interpreted by artists in their work, thus ‘restoring its complexity and diversity, meaning and value’.

The projects are ordered under the themes of ‘the invisible community’, 'aesthetics, politics and the institution’, ‘the memory of the place’, ‘urban experience’, and ‘public intimacy’. Many of the same projects are presented in the documentaries, but under different titles and grouped by city or geographical region. What they have in common is that they are all about artists who operate in the midst of everyday life and are motivated by a profound engagement with social and civic issues, oriented towards the ‘location’ in the broadest sense of the word. The creative practices range from commissioned art projects to autonomously initiated, multidisciplinary research projects that involve sociology, architecture and urban planning, in which the art (and artist) disappear from view.

The project Immaginare Corviale by the Osservatorio Nomade is a fascinating example of such a research network based in Italy, with artists, architects and researchers from various disciplines and countries participating in it. Corviale is a large-scale urban development near Rome that dates from the 1970s. It provides housing for 8,500 inhabitants and has to contend with an image problem. Osservatorio Nomade set out in search of the (utopian) vision and the original programme that underpinned the conception of the complex. By interviewing its residents, involving them in the research and initiating channels of communication in reaction to the absence of social relationships, the Osservatorio Nomade endeavours to provide space for the birth of a collective imagination. This is not a vision projected from above, as it was at the time of Corviale’s design, but a shared ideal that can contribute to its transformation.

Comparable projects are found elsewhere. Jeanne van Heeswijk worked with De Strip in Vlaardingen, situated in a similar conglomeration, with the goal of creating space for ‘cultural production’ for and by the residents. With I and Us, the Campement Urbain focused on a ‘dreamed place’ in the provincial town of Servan in France, in the midst of a raw reality characterized by problems with regard to multiculturalism, poor housing and unemployment. Despite their differences, these suburban reaches of Rome, Vlaardingen and Servan share the key characteristics of a modern metropolitan agglomeration and therefore call to mind the arguments of the American researcher Miwon Kwon.1

Kwon describes the continued stretching of the notion of ‘site’ in the site-specific practices of artists. The ‘site’ is no longer tied to a physical location but can also be a community or a discourse, and the subjects of those practices are not limited to art proper. She sets this development alongside the loss of ‘place’ in the modern city. Increasing indifference and fragmentation of the contemporary urban space result in a sense of alienation, while the desire to belong somewhere as the basis for a sense of identity and security remains unchanged. It is precisely here that Kwon sees a role for art as cultural mediator. She calls for the development of models that provide space for that nostalgic yearning for place and identity as well as for the recognition of the contemporary urban condition. It is interesting to peruse the projects in The [Un]Common Place with Kwon’s ideas at the back of one’s mind. However, it won’t get you a long way: in the wealth of projects presented the information is limited, lacking in both detail and an account of their course and outcome over the longer term.

This raises further questions. In the projects mentioned, the ‘community’ is also a component of the ‘site’. The facilitators focus on what is important to the residents and strive after community participation – an artistic practice with many present-day forms but also with distinguished predecessors, notably American examples in the book by Kwon. She describes activist ‘public art’ with the political aspiration ‘to empower the audience’. Such projects receive due recognition as regards certain respects, but are also fiercely criticized because of the exploitation of the communities involved, the propagation of typically stereotypical designations, the transience of the engagement, and the reduction of art to an inadequate form of social work. The relationship to that ‘tradition’ is not addressed in The [Un]Common Place, nor is there a link to current forms of artistic activism, in which the quest is to discover new variants of community spirit in the guise of networks and subcultures. The absence of an exploration of such links and a historical and theoretical frame of reference is regrettable.

Pietromarchi tries to redefine the term ‘public space’ from a European perspective, when it is a redefinition of the public role of art and artists that seems pertinent to these projects. And then there is also the guarded intercourse with the very notion of art. While ‘art’ is mentioned in the title of the book, its expansion to embrace a more general notion of culture termed ‘creative practices’ is already apparent in the introduction. In its focus on art as a form of cultural criticism, which also encompasses spaces, institutions and questions that do not properly belong to art, The [Un]Common Place keeps pace with contemporary practice and discourse. It signals a strained cultural engagement with a penchant for public places and the involvement of a broader field. This means that the boundary between art and non-art becomes blurred, and that raises questions. Big subjects are placed on the agenda in this book, and it employs complex concepts. Despite the sometimes top-heavy terminology, a great deal remains undefined, and contexts and frameworks are left in rudimentary form.

The [Un]Common Place provides an inspiring overview of a lively practice with its fascinating examples. These are very much worth the effort, and in that sense I would call for more! Overall, however, I would like to see deeper exploration, and then in terms of context and the development of a theoretical framework.

1. Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another. Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, Massachusetts / Londen: MIT Press, 2002).

Mariska van den Berg is an art historian, and until 2010 worked as a curator at SKOR | Foundation Art and Public Space. Lately, she has been investigating forms of appropriation in public space, under the title ‘Reclaim: toe-eigening en publiek domein’, for which she received a research grant from the Netherlands Foundation for the Visual Arts, Design and Architecture (Fonds BKVB).