All My / Our Relations

Can Posthumanism Be Decolonized?

July 7, 2016essay,

Indigenous scholarship in the Americas offers an alternative to the dualistic focus of Western science in embracing a wider and more animated body of relations. Sebastian De Line brings this line of investigation into contact with Karen Barad’s thoughts on wave diffraction and the unpredictability of matter, pulling from the contingent relationships that form during the classic double-slit experiment. The unravelling of these takes on science, stemming in the first case from spirit and in the second from controlled experiment, unearths a platform to address our web of relations that does not dispose of past models but rather integrates them. ‘All My / Our Relations’ is part of the Open! COOP Academy series Between and Beyond.

In the Cree and Michif (First Nations and Métis) languages, Niw_hk_m_kanak means ‘all my / our relations.’1 Within this essay, I endeavour to explain and weave together a possible collaboration between Niw_hk_m_kanak and Karen Barad’s notion of diffraction. I believe these philosophical concepts can benefit each other and expand upon a discourse of science and philosophy – without relying on Cartesian dualities (nature / culture, human / animal, object / subject) – through Indigenous scholarship, especially that of Kim TallBear, Audra Simpson, Leroy Little Bear and Glen Coulthard.

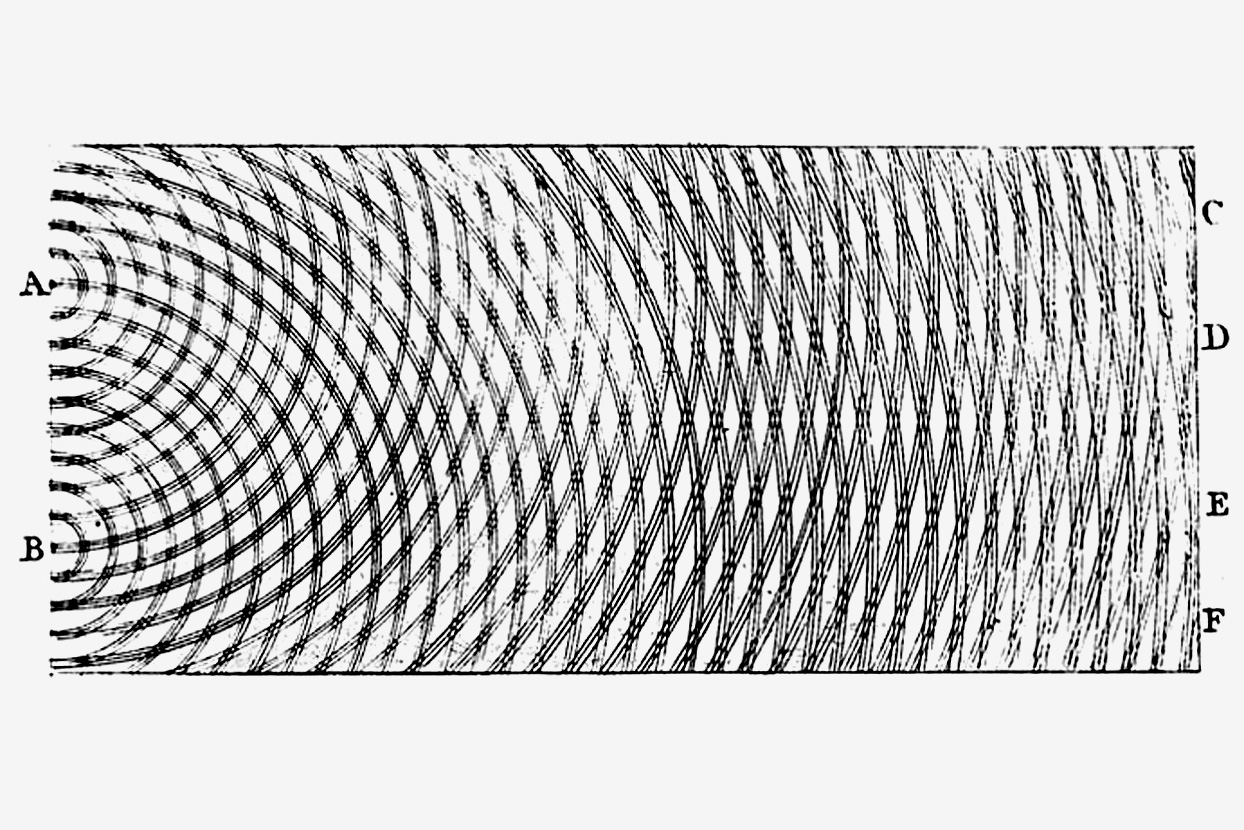

Rather than Indigenous sciences acting in parallel to Western philosophy and physics, Little Bear, founding Director of Harvard University’s Native American Studies programme, proposes a collaboration between Indigenous and Western sciences. I take up this purview in connecting the non-dualistic Indigenous paradigm of all my / our relations to diffraction as observed in the Western scientific field of quantum physics. Diffraction is seen in the two-slit experiment, in which energy waves (in light or water) pass through a barrier with two openings, creating single wave or diffraction patterns. Energy, on a quantum level, can behave unpredictably producing contingent outcomes:2 electrons deviate while being monitored by a recording device during these experiments, forming irregularities in their behaviour. The irregular behaviour of quantum matter reopens a line of philosophical inquiry within phenomenology, questioning the animacy and agency of materiality. If water is made of quantum matter and therefore scientifically proven to be animate, what can be said of the rights of water and its own agency or well being? This line of inquiry is not new to Indigenous beliefs.

Three Tenets of All My / Our Relations

On the 24th of March 2011, Little Bear gave a lecture at Arizona State University entitled, ‘Native Science and Western Science: Possibilities for Collaboration.’ In the below section he lays out what he refers to as the three tenets of native science, summarizing all my / our relations:

The first tenet of the native paradigm is what we refer to as constant flux. If you were to imagine this flux is animated, you would see a constant motion or energy waves, light and so on, going back and forth. Things are forever in motion, things are forever changing. There is nothing certain. The only thing that is certain is change. Things are forever moving, things are forever dissolving, reforming, transforming. A second part of the native tenet of flux is flux itself. Everything in existence, everything in creation, consists of energy waves. In classical physics, we talk in terms of matter, particles, subatomic particles. In the native way, we talk in terms of energy waves. Those energy waves are very special because it's those energy waves, not you, that know. All of us are simply combinations of energy waves. Spirit is energy waves. All it means when we die is that particular combination becomes dissipated. Energy waves are still there. A third part of the paradigm is that everything is animate. There is nothing in Blackfoot for instance, that is inanimate. Everything is animate. Everything, those rocks, those trees, those animals all have spirit just like we do as humans. If they all have spirit, that’s what we refer to as, all my relations.

In the Indigenous paradigm, all matter is made up of energy waves (diffraction waves) and spirit is the name given to these energy waves. Everything is fluctual: composed, decomposed and recomposed of energy waves which is also known as spirit.

All My / Our Relations

Niw_hk_m_kanak are the words spoken during opening and closing ceremonies used by Cree and Métis nations including Blackfoot and Haudenosaunee Confederacies. The words acknowledge and bless all that is in the continuum, continually in flux, in all our relations; all matter, all energy waves that are in contingent relationality through a familial network (consisting of four main assemblages: ancestral, preferential, involuntary and ordained).

All my / our relations is not only a ceremonial acknowledgment but a philosophical proposition. The proposition can be deduced as such: all refers to a whole, all matter, all factors, all contingencies; my means belonging to or associated with that which is beyond singularity; interchangeably our is associated with belonging to more than one; and relations, refers to both an interconnectivity and familial relationship to all matter. This relationality is similar to the Spinozian ethical proposition which works on the principle of three rather than two (dualism) bodies in relation to each other: a body at rest or in motion is affected by a second body at rest or in motion that is affected by a third body at rest or in motion.3 What distinguishes all my / our relations from Spinoza’s rhizomatic fractalism is that all my / our relations places emphasis on ‘my’ or ‘our’ as the interlocker of belonging, whereas Spinoza’s proposition states that the body is the interlocker. Yet Spinoza does not specify an intimacy in these affected bodies who are in relationality. He does suggest that all bodies are animate to some degree by way of their ability to affect and be affected, but all my / our relationality is more explicit in its statement, calling awareness to the responsibility of animate bodies (matter) for each other. Animateness is the interlocker of relationalities between all matter. It is not exempt from materialism, Niw_hk_m_kanak or all my / our relations is similar to new materialist thinking but it is “pre-materialist” and “pre- / post-humanist”.

Haraway’s Diffractive, Inappropriate / d Others and All My / Our Relations

Energy waves form diffractive patterns when they encounter obstacles. Diffraction, as introduced by Donna Haraway in her text ‘The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate / d Others,’ describes an interruption rather than a reflection. She uses diffraction rather than reflection, given reflection requires objective distance from that which is being observed, thereby objective to a subject. As the one observed (particularly with subjectivities such as racialized, gendered and disabled embodiments that can be intersectional within one body) the ability to be reflexive and sit at the objective end of the mirror, is obstructed with the location of this mirror controlled by a jagged patriarchal overhang. If normative society deems an Indigenous person, a person of colour, queer and / or disabled person or any person (or combination of these identities) as falling outside of a system of norms and codes, these embodiments of difference create contingent (change) processes regardless of how they are judged. ‘Inappropriate / d’ speaks to being viewed as an other, being inappropriate in the eyes of the observer, and of a refusal to be culturally appropriated by one being perceived. Being inappropriate is about difference, differences that are viewed with moral friction.

[D]iffracting rays compose interference patterns, not reflecting images. The ‘issue’ from this generative technology [...] might be kin to Vietnamese-American filmmaker and feminist theorist Trinh Minh-ha’s ‘inappropriate / d others.’ [...] Trinh’s phrase referred to the historical positioning of those who cannot adopt the mask of either ‘self’ or ‘other’ offered by previously dominant, modern western narratives of identity and politics.4

The survival and resistance to colonization by Indigenous sovereign nations is diffractive. Within the priorities of feminist activation and constant development of anti-oppressive strategies, it’s nonsensical to practice Western ontology alone. So how can one work with Indigenous philosophy who is not Indigenous without perpetuating appropriation? Decolonization is already a priority within the humanities, particularly through an intersectionality with gender and sexuality studies. The title of Trinh T. Minh-ha’s monograph clearly states: Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism share a common othering.

Outside of academia exist contemporary developments of self-determined Métis communities and nations in relation to their nested sovereignties within a Canadian hegemonic, fiduciary body of government.5 The specificity of Métis identity and history is unique in that it is a result of historic colonial contact and entanglement. Relationalities between Indigenous and settler communities, traditional and hybrid identities whose cultural, social and partial self-governing constructs are a mixture of Indigenous and Canadian constitutional models which include leadership roles as senators and ‘captains of the hunt’:

The captains of the hunt were true representatives of the people; their council was a genuine though extra-legal government. Even after the hunt declined in economic importance, its political organization had a social significance that continued.6

The economic importance of the hunt as an issue has revived among many Métis nations and individuals who still depend on seasonal hunting to support their families and communities. This also extends to commercial fishing licenses which support the economy of particular communities whose territories and traditions are tied to an interrelationality of all my / our relations: between water, land, nonhuman animal, human animal and various animate matter that supports and is affected through trade, nourishment and cyclical replenishment. Within all my / our relations, obstacle and entanglement are inevitable. Various strategies of nested sovereignty and self-determination form diffractions. Diffraction is not a singular occurrence: it is situational.

Barad’s Diffraction and All My / Our Relations

Little Bear’s articulation of all matter as made up of energy waves fits with a classically occidental scientific definition of wave diffraction. In chapter two of Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, ‘Diffractions: Differences, Contingencies, and Entanglements That Matter,’ Karen Barad addresses the subjective context of diffraction:

In particular, feminist science studies scholars have argued that reflexivity has proved insufficient on at least two important grounds. First of all, for the most part, mainstream science studies (in all its various incarnations) has ignored crucial social factors such as gender, race, class, sexuality, ethnicity, religion, and nationality. The irony is that while these scholars insist on the importance of tracking ‘science-in-the-making’ by attending to specific laboratory practices, for the most part they continue to treat social variables such as gender as preformed categories of the social. That is, they fail to attend to ‘gender-in-the-making’ – the production of gender and other social variables as constituted through technoscientific practices.7

As Barad states, the negligence of mainstream science studies regarding an inclusion of social factors such as gender, race, class, sexuality, ethnicity, religion and nationality to include these factors within scientific practices, modes of research and pedagogy is highly problematic and remains patriarchal. Indigenous scholarship has been vastly underrepresented due to gendered and ethnographically dismissive, misunderstood and over-simplified interpretations. This is due to a prevailing and permissive, colonial-anthropological view of women in general and Indigenous people being perceived as objects of fetishization through the racialized systematic oppression, assimilation and genocide of Indigenous people, Indigenous communities and primitive accumulation of capital – and labouring bodies.8 Case in point, within the 1876 ‘Indian Act’ of Canada, prohibition of Indigenous people from attending university was punishable by a loss of Aboriginal status or forced assimilation. Loss of status would have innumerable consequences including inaccessibility to living on reservation lands, therefore choosing to study at university could mean a risk for one’s family or community loss and estrangement. It was not until the early 1970s that Indigenous people began attending Canadian universities, sporadically. From a feminist perspective, I see it as imperative to address these issues of a colonial past which continue to erase Indigenous innovation and contribution to fields such as philosophy and science. Indigenous culture is continually cast in an archaic light, primitivized and romanticized by Western culture. Within an academic context, the production of knowledge in Indigenous lands needs to include localized Indigenous knowledge systems within its practices if it is to actually perform non-hegemonic diffractive processes.

Barad’s Agential Realism and All My / Our Relations

Poststructuralism attempts to address this fragmented process by including the reader as the central figure of an embodiment of knowledge, while aiming to approach meaning as an assemblage of collective perspectives and differences. The approach investigates how to think through meaning in a non-authoritative way, by introducing concepts which show how systems of power function to objectify subjects and control behaviour (Foucault)9 and operate performatively (Butler),10 leading to agency as a way to move through repression. Performativity also opens a space in which deviance can operate outside, or wherein morality is a clause.11

All my / our relations is in relationality to all nature and all matter is culture. Culture is not an extrapolated abstraction, interpretation or ritualized representation observed in nature by outsiders – so-called “outsiders” are intra-actively part of nature. It is relationality in and of itself to all matter, all that is known, beyond knowing or unwilling to be known. The unwillingness to know is the aspect of relationality commonly used to uphold symmetrical processes that fail to adequately account for contingency. Symmetry is limited by the capacity to factor in variables of difference, complexity or ambivalence. All my / our relations seem to be positioned deep within networks of belonging, not at a starting point or from an objective end point in which to reflect. It does not presume to answer the question of what everything is therefore giving it structure and place; it focuses on relationality while operating from within process and it makes this process personal, intimate and shared.

Stating that all matter is made up of spirit and that spirit is what is scientifically called energy waves is not anthropocentric, nor is it anthropomorphic. Both anthropocentricism and anthropomorphism centralize the human as the key figure upon which matter and othering is categorically objectified and revolves around. Anthropomorphism is a classification which attributes human characteristics to anything observed that acts in kind with human behaviour or standards. It also attempts to qualify anthropomorphic behaviour as a form of desired mimesis, copying a supposed superior behaviour of humans. Theriomorphism, on the other hand, attributes animal characteristics to humans. All my / our relations is neither theriomorphic, as its philosophical proposition places no grid or hierarchy among what is defined as all, nor is it anthropomorphic. Little Bear compares this grid-like structure to superimposed surveying grids placed upon the earth in order to map and quantify potential usages of location and materials. This, in turn, affects inhabitants in relation to a geocapital model and where they are situated in terms of labour, cultural capital, marketability, production or non-usage and therefore vulnerable to erasure.

Briefly, Barad describes agential realism by stating that ‘knowing, thinking, measuring, theorising, and observing are material practices of intra-acting within and as part of the world.’12 It is possible to fit agential realism within an understanding of the potential breadth of all my / our relations, but it must be noted that these modalities are still viewed with an occidental, compartmental lens. Her solution to this problem is through intra-action: ‘Interacting with (or rather, intra-acting “with” and as part of) the world is part and parcel of seeing. Objects are not already there; they emerge through specific practices.’ 13 Intra-action works similar to our relations in that it is a binding agent, gluing subjectivity to all matter. Where this statement falls short is that it is limited to the perception of ‘seeing’ rather than explicitly saying ‘experience.’ Much of Barad’s work aims to stitch together what analytic philosophy has deemed segregated academic fields, as she notes: ‘I also use “ethico-onto-epistemology” to mark the inseparability of ontology, epistemology, and ethics. The analytic philosophical tradition takes these fields to be entirely separate, but this presupposition depends on specific ways of figuring the nature of being, knowing, and valuing.’14 Returning to the embracing, calling-in activation of all my / our relations, I see these problems as within the scope of that proposition. What needs to be given more deliberation is how agential realism deals with localized capitalistic impacts, sociopolitical and geopolitical environments and surrounding constructs that affect the relational assemblages of all matter.

The mutual urge of ethical accountability is built within the Baradian model and the all my/ our relations model. All my / our relations doesn’t delve into the messiness of fragmentation: it addresses invariables, chaos or measurement through constant flux. Constant flux is immeasurable because it is always in motion and contains innumerable contingencies. All that is left is to exist within a process of constant flux. What all my / our relations is not doing is proposing one model of government to suit it. Rather, all systems and cross-networking between governments still exist within this paradigm. It does not aim to solve the problems of how we relate with each other.

Returning to the problem that Barad addresses within Western models of philosophy, I find support in how Brooke Holmes deals with dualism (that Barad sutures with intra-action) within Greek philosophy by proposing a sympathetic cosmos. In her article, ‘Proto-Sympathy in the Hippocratic Corpus,’ she gives a historical account within the tradition of Greek, antiquated medicinal arts. She cites Galen’s description of sympathy which is beyond a body but is found within all: ‘everything is in sympathy’ [πάντασυμπαθέα].15 Perhaps Holmes’s model of a sympathetic cosmos can put some of these occidental quarrels to rest and allow us heal.

The Familial Bond of All My / Our Relations

Familial systems often consist of four main assemblages: ancestral, preferential, involuntary and ordained. In its minute form, a family structure comprises one entity and another. These entities do not need to be the same: nonhuman animals together with other nonhuman animals, nonhuman animals with human animals, nonhuman animals with trees or plants, human animals with trees or plants, the potential of familial assemblages are without exception. What adheres a familial assemblage? It is said that will adheres an assemblage. Yet within an involuntary family structure, is it will that fuses its social contract?

Constant flux is the first tenet of Indigenous science and is based on the principle that all matter is in movement and everything changes. If constant flux is what adheres an assemblage, then an assemblage is also in constant flux. It is not rigid or static. Is an ancestral assemblage in constant flux? Certainly. Ancestral assemblages adhere with other ancestral assemblages, with preferential assemblages, with all other assemblages and these patterns change over spans of time and proximity of relationality. This can also be said of involuntary and ordained assemblages, who appear to be fixed or rigid while yet they are permeable to constant flux. This permeability is what allows constant flux to pass through all matter and assemblages. Will is a modality of permeability.

What then of law? Are laws necessary if everything is in constant flux? Rather than dictate if and what laws would flow within constant flux, as in fact all flows within constant flux, including structures seemingly rigid as illustrated previously, it is not altogether necessary to employ law. Agreements or consented negotiations can be made to serve a structure where a modality of will can be activated for any given span of time and space. Will, being a contingency, may influence where flow is directed in constant flux.

The current situation of nation-state construction and territorial ownership as rigidly guarded assemblages are problematic in that they monopolize societal views and governance. Should these models of nation statehood become replaced by those in alignment with the three tenets of the Indigenous paradigm, individual and assembled entities will have the potentiality of self- determination while remaining in relation.

Great Path: Meeting Occidental Philosophy and Physics Halfway

Paul Chartrand, Métis scholar and practicing lawyer on law and policy of Indigenous people, and Leroy Little Bear, Blackfoot scholar on Indigenous Studies, open up a discourse on the significance of all my / our relations. At first glance, to Western eyes all my / our relations appear to be only an incantation to call upon and acknowledge ancestral lineages. Yet, what has not been commonly understood is that all my / our relations is a basis for science, law and philosophy within Indigenous cultures, used by many nations such as the Cree, Métis, Blackfoot and Haudenosaunee Confederacies.

Little Bear provides an interpretation of the three tenets of Indigenous science culminating in all my / our relations, while suggesting a collaboration between Indigenous and Western sciences from its departure. From this point on, I seek to specify the potentiality of this collaboration within feminist philosophy in relation to diffraction and posthumanism. The scope of this proposition is still in its incubation phase, yet I believe that all my / our relations provides a means to eliminate the necessity to return to occidental philosophy for hypothesizing realities partially known to us which continually complexify and unfurl. What I am certain of is that the issue of negligence concerning Indigenous contributions to scientific and philosophical knowledge needs to be addressed within academic institutions in the Americas. The ethnographically insulting perspectives cultivated within academia, public schools, government institutions and society that negatively reflect and anthropologically misinterpret Indigenous culture, history, science and art practices only further perpetuate geopolitical, economic and social stratifications. How can we say that colonialism is in a post-period? Reservation systems, poverty, inaccessibility to qualitative conditions privileged through settlement claims of ownership and authority still exist. In order to dismantle hegemonic systems of knowledge and economic production, it is necessary to begin with a philosophical base that has the capacity to embody care and accountability. Through preserving colonial vestiges of canonical knowledge, rather than understanding what it means in the statement ‘all matter is animate,’ the human animal never moves out of the human and into the posthuman. In order to understand our role in these diffractions, it will require more than what is provided by occidental systems of knowledge.

1. Paul Chartrand, ‘Niw_Hk_M_Kanak (“All My Relations”): Métis-First Nations Relations,’ National Centre for First Nations Governance, 2007, 1.

2. ‘In physics, there is a very simple machine that can be used to find out whether it is a particle or a wave, and it is called a two-slit apparatus. When you take a bunch of balls and shoot them randomly at two slits, what you find is that most of the particles wind up directly across from the two slits. You get something called a “scatter pattern.” You can think about the fact that if I am wildly throwing tennis balls in this room at the doorway, most of them are going to wind up right across from the doorway and a few of them will scatter to the sides. In contrast to that, think of a wave machine, making a disturbance in the water. And when the disturbance hits this kind of “breakwater” with two holes in it, what happens is that the disturbance bulges out on both sides and you get these kinds of concentric, overlapping circles that get forced through, just like when I drop two rocks in a pond simultaneously, I get an overlapping of concentric circles. That is a diffraction pattern and what you see is that there is a reinforcing of waves.’ Rick Dolphijn and Iris van der Tuin, New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies (London: Open Humanities Press, 2012), quod.lib.umich.edu.

3. ‘[T]he motion and rest of a body, must arise from another body, which has also been determined to a state of motion or rest by a third body.’ Baruch Spinoza, ‘Proposition II,’ The Ethics: Part Three, On the Origin and Nature of the Emotions (1677), www.yesselman.com.

4. Donna Haraway, The Haraway Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004), 69.

5. Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2014), 12.

6. D. N. Sprague, Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885 (Waterloo, CA: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1988), 39.

7. Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2007), 87.

8. See Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch (New York: Autonomedia, 2009).

9. ‘It had already been constituted outside the legal apparatus when, throughout the social body, procedures were being elaborated for distributing individuals, fixing them in space, classifying them, extracting from them the maximum in time and forces, training their bodies, coding their continuous behaviour, maintaining them in perfect visibility, forming around them an apparatus of observation, registration and recording, constituting on them a body of knowledge that is accumulated and centralized.’ Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Random House, 1995), 231.

10. ‘In this sense, gender is not a noun, but neither is it a set of freefloating attributes, for we have seen that the substantive effect of gender is performatively produced and compelled by the regulatory practices of gender coherence.’ Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1999), 33.

11. ‘[...] Michel Foucault and Judith Butler blast the tenets of humanism and representationalism in an attempt to harness the force of this explosion to garner sufficient momentum against the threshold escape velocity. Each of these powerful attempts rockets our cultural imaginary out of a well-worn stable orbit. But ultimately the power of these vigorous interventions is insufficient to fully extricate these theories from the seductive nucleus that binds them, and it becomes clear that each has once again been caught in some other orbit around the same nucleus. Suitably energetic to cause significant perturbations, nonetheless, the prized ionization is thwarted in each case by anthropocentric remainders.’ Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, 135.

12. Ibid., 90.

13. Ibid., 157.

14. Ibid., 409.

15. Brooke Holmes, ‘Proto-Sympathy in the Hippocratic Corpus,’ in Hippocrate et les hippocratismes: médecine, religion, société, ed. Jacques Jouanna and Mike Zink (Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 2014), scholar.princeton.edu, 124.