Common Civil and Social Disobedience

April 13, 2005review,

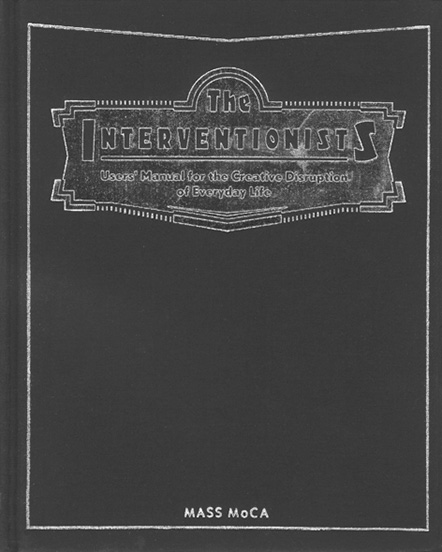

Nato Thompson and Gregory Sholette (eds), The Interventionists: Users’ Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life, MASS MoCA & MIT Press, 2004, ISBN 026220150X

In the supremely pluralist and heterogeneous world of contemporary art there are barely any new ‘isms’ evolving – at best generic terms such as ‘Brit Art’ and ‘relational aesthetics’. That, at least, has been the prevailing idea since post-modernism. Current art, however, according to the catalogue for the exhibition ‘The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere’ at MASS MoCA, is an incubator for a recently introduced ‘ism’, imbued, moreover, with a battle-ready élan: interventionism.

Although the ‘freaky’ graphic design is a permanent distraction and the emphasis is primarily on the American art scene, this publication is worth the effort in every sense. This is not simply because of the collection of highly divergent elaborations of the key concepts of the French Situationists: détournement (a subversive rendering of a popular code system, such as advertising message, feature film and cartoon), and the dérive (subversive insertion of an activity, instrument or vehicle in an urban setting). The catalogue is also interesting because of the enormous, often dryly comical inventiveness and the well-intended motivation of this newest crop of political artists – an engagement that is based on a common civil and social disobedience.

The artistic methods used are in line with this: we recognize the anarchist, the anti-globalist, the political activist, the street nomad, the urban guerrilla and the proletarian consumer. For example, in direct reference to the house style of the international fashion chain Mango, the Spanish collective YOMANGO (which means ‘I steal’) produces a bag with a magicians conjuring compartments in order to be able to shop like the proletariat: ‘YOMANGO is like all other major brand names about the promotion of a lifestyle.’ With the white, inflatable one-man shelters by Michael Rakowitz, the less well-off are likewise helped on their way. Connecting the conduits to the left and right of these shelters with the external vents of a mall or apartment complex creates a sheltered spot.

The catalogue tells us that Krzysztof Wodiczko developed and has been producing modified shopping carts / sleeping cabins with cupboard and storage for the homeless since 1987. Lucy Orta is one of the pioneers in portable architecture with, among other things, her sleeping-bag shelters. The catalogue makes one realize to what extent Wodiczko and Orta paved the way for trends from the late 1990s to the present with the irrepressible references to, and production of, tents, caravans, mobile homes, retreats, canopies, kiosks, clothing variants and survival and backpacker sets. In the catalogue, curator Nato Thompson therefore argues that ‘the entire world feels unsettled’.

The appearance of technically advanced utilitarian equipment, including graffiti-spraying robots and fully automatic survival units made for protest demonstrations, leads one to suspect that the interventionists hope to recruit sympathizers. The ‘event’ and performance-like expressions expose socio-economic structures in a somewhat pedagogical manner. The Flash animation on top of a taxi by the HaHa collective displays constantly changing comments by residents and users about their city’s infrastructure. ‘Reverend Billy – the credit card exorcist’, founder of the ’Church of Stop Shopping’, holds his fire-and-brimstone sermons with a megaphone and dressed in full regalia in a capitalistically infected zone like The Disney Store. Decidedly problematic is the ‘I’ll throw a custard pie in the face of this figurehead’ antics of a pie-throwing brigade. Bill Gates has been served a pie like this, and Milton Friedman.

An artist can often disseminate a political message with greater success and thus be an activist (or even a political leader). However, not every activist is an artist. In order to be sure of attention, activism relies on expression and publicity, but the idea that an act of resistance is therefore also an artistic act is a misapprehension. Since in practice the boundary between art and activism is extremely vague, every simplistic statement is one too many. In the catalogue, writer Gregory Sholette points out a similarity between interventionism and a protest organization such as Greenpeace, since ‘they stress pragmatic and tactical action over ideology’. As an art critic, you become an activist in your own right; the chaff has to be separated from the corn. If the activism is ‘base’, without visual and semiotic layering, lacking in transformation and exaltation, then it is simply not art.

Another point of criticism is the selection of artists. The interventionists who infiltrate in a business and / or organizational context while retaining their autonomy are conspicuous by their absence, no matter how high-profile their position. Do they have too little street awareness? Are they overwhelmingly doomed to a compromise, under the spell of the Hugo Boss emporium? We don’t find out, despite Sholette’s observation that ‘art and business’ are increasingly interdependent.

The catalogue holds the attention nonetheless, certainly as far as the text contributions are concerned. The introduction by Nato Thompson, for example, reads like an intriguing plot. In an explanation for the rise of the interventionists he refers, among other things, to the inflation of ‘political representation’, to the socio-economic changes in the 1990s, and the rise of the ‘culture industry’ in particular. Thus passing the review – for my contemporaries it will be a feast of memories – are Bill ‘saxophone’ Clinton’s promotion of the pop group Fleetwood Mac, the commercial incorporation of Nirvana’s music, and – against the (critical) background of Naomi Klein’s book No Logo – the advertising campaigns of certain mighty multinationals with Che and Gandhi playing the lead roles. According to Thompson, such segments of underground culture annexed by capitalism are the reason why the interventionists migrate to relatively impalpable political fringes.

In his essay, Gregory Sholette goes in search of a correlation with Soviet Constructivism – deemed highly desirable by the interventionists – associating interventionism in guarded terms with the short-cut thinking of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, the authors of Empire. This book is a hybrid of modernist progressive thinking and post-modern conclusions that until 9 / 11 was the hope of a bankrupt left wing. The interventionists supply instruments and opportunities, Sholette says, not so much for the masses but for the multitude (the title of the recently published fruit of Hardt & Negri’s pens is Multitude). Is Sholette being reserved because he does not yet dare state aloud that interventionism has moved beyond post-modernism? Interventionism as the signalling of a new developmental era is indeed revolutionary news.

Marjolein Schaap was an Amsterdam-based art critic, project initiator and curator.