Common Knowledge

A Virtual Round Table on the Crisis in Higher Education

May 23, 2015editorial,

In response to the protests and occupations that have rocked universities and art schools from Montreal and Toronto to Amsterdam and London, Open! organised a virtual round table on the crisis in higher education and presents a constellation of short texts by professors, lecturers, PhD candidates, students and alumni, as well as by artists and activists.

In recent weeks, student and sometimes faculty protests and occupations have rocked universities and art schools from Montreal and Toronto to Amsterdam and London (where the University of Arts, LSE and King’s College were all affected).1 This transnational wave of collective action has its roots in systemic issues that earlier led to the 2010 and 2014 UK student protests and the 2012 protests in Quebec. The latter saw the emergence of the “red square” symbol, which this spring was taken up by the students who appropriated the Maagdenhuis – the University of Amsterdam’s headquarters – and by the Dutch De Nieuwe Universiteit movement in general.2

Of course, a movement like this doesn’t just spring up out of nowhere; last year’s occupation of the church at VU University Amsterdam by students in the Earth and Life Sciences faculty had similar causes as the much more visible Bungehuis and Maagdenhuis occupations by UvA humanities students this year. Both the VU’s Earth and Life Sciences and the UvA’s Humanities departments were facing a Texas Chain Saw Massacre treatment, with programs being merged or abolished altogether, and dozens or even up to 150 jobs being cut. Meanwhile, Erasmus University in Rotterdam announced that it was getting rid of its Philosophy faculty, treating it as excess baggage; shades of Middlesex University, which closed its influential Philosophy department in 2010.

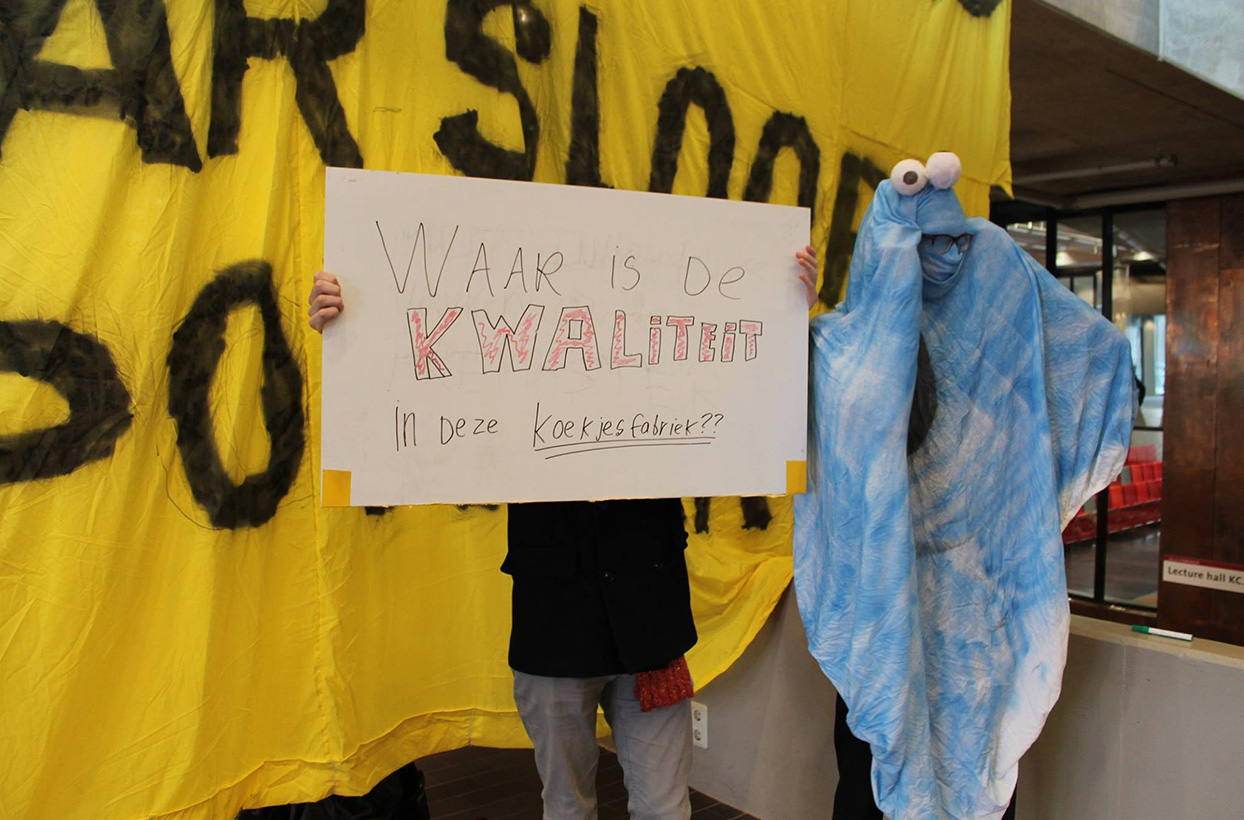

If Holland, and continental Europe in general, are just as affected by the implementation of neoliberal policies and the financialisation of universities as the UK, Canada and the US, the effects differ: in the Netherlands, the protests were sparked not by sky-high tuition fees inaugurating a life of debt but by the aforementioned cuts in programs and staff, and by the resulting sense that the university is being turned into a “cookie factory”, churning out graduates on the cheap. The amount of funding Dutch universities receive from the state per student continues to dwindle, and this has precipitated a growth drive that, in a proper Freudian manner, reveals itself to be a death drive. As the total number of students continues to grow, the strain on the budget only becomes more intense.3 A few years ago, the Humanities department staff at one Dutch university were informed that as a result of this mechanism, they would have to expand by some fifteen percent each year in order to safeguard their budget. Meanwhile, there is an increasing dependency on third-party funding and on the state’s Stalin-like, neoliberal funding body, the NWO – which steers Humanities research via its near-exclusive focus on “the creative industries” and a technocratic understanding of digital humanities.

That the funding calculus may pan out differently per university and even per faculty within a university provides ample room for infighting and backstabbing.4 Furthermore, the protests often remain localized, and students are attacked in the media and online platforms as privileged and spoiled brats—even though the Maagdenhuis occupiers insisted on framing their actions as part of a more general struggle of a steadily worsening status quo, and on the forging of alliances with groups who are in far worse legal and economic situations. The aim of this “virtual round table” is both to learn from their actions and provide a platform for thinking beyond this particular situation.

The strategy in presenting a constellation of short texts by professors, lecturers, PhD candidates, students and alumni, as well as by artists and activists, is to further the analysis of the present situation (in the Netherlands in particular) and the development of strategies and practices after the police evicted the Maagdenhuis occupiers on April 11. But the “new university” doesn’t need to be something that is merely discussed ad infinitum as a beautiful project forever awaiting its actualisation. As some of our contributions stress, the Maagdenhuis was the new university; with its daily program of talks and discussions; the students turned the production and problematisation of knowledge into a matter of common concern. As everyday praxis, as a reconfiguration of academic protocols, the Maagdenhuis “reappropriation” was both political and aesthetic practice; it was a commoning of the financialised university that was for all to see and sense, and participate in.

In the first volume of his Social History of Knowledge, Peter Burke notes that while most Renaissance humanists were trained at Europe’s universities, these institutions proved inhospitable to their intellectual practices. From Petrarca and Ficino to Erasmus, none of these scholars and intellectuals ever received tenure. Erasmus was offered various positions but took great pains to remain independent, or to juggle his dependencies in such a way that no regular university job was required (which makes Erasmus University Rotterdam the second most ironic university name in the Netherlands, right after the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam). The important debates occurred not at the university, but at the humanists’ more informal counter-institution: the academy.5

Anachronistic and perverse though it may seem to invoke these precedents at a moment when posthumanist theory holds sway over much of the humanities (or should that be: the posthumanities?), we find ourselves in a strikingly similar situation. Now that the institution has been occupied by a managerial caste that imposes “financial necessities”, some opt to leave, others withdraw. What are the strategies for reappropriation, for infiltration? How do we construct actual academies – no matter how temporary and fragile – within academia?

1. news.nationalpost.com, www.theguardian.com, www.timeshighereducation.co.uk, www.theguardian.com

3. www.vsnu.nl

5. Peter Burke, The Social History of Knowledge: From Gutenberg to Diderot (Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press, 2000), p. 36.

Sven Lütticken is a member of the editorial board of Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain. He teaches art history at VU University Amsterdam; is the author of several books, including History in Motion: Time in the Age of the Moving Image (2013); and writes regularly for journals and magazines including New Left Review, Afterall, Grey Room, Mute and e-flux journal. At the moment he is working on a collection of a essays under the working title 'Permanent Cultural Revolution,' and editing a reader on art and autonomy. See further: www.svenlutticken.org.

Jorinde Seijdel is an independent writer, editor and lecturer on subjects concerning art and media in our changing society and the public sphere. She is editor-in-chief of Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain (formerly known as Open. Cahier on Art & the Public Domain). In 2010 she published De waarde van de amateur [The Value of the Amateur] (Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam), about the rise of the amateur in digital culture and the notion of amateurism in contemporary art and culture. Currently, she is theory tutor at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and Head of the Studium Generale Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. With Open!, she is a partner of the Dutch Art Institute MA Art Praxis in Arnhem.