Cyborg Politics

Notes for a Lexicon

November 16, 2016artist contribution,

Sometimes it is hard to believe that we’re living in the future that has already taken place. We go on speculating about the prospective forms of power, in which access to knowledge is equipped with information-, nano- and bio-technology along with cognitive science. What it seems we fail to recognize is that we already are a part of the new state: a political corporation that is not a mere extension in scale and scope of already existing precedents, but a completely novel form of government. While the new state might still be in the process of comprehending its own capacities, power-knowledge within it is already fully deployed via technology. Furthermore, knowledge and its dissemination are interweaved so radically it is no longer possible to distinguish between technological and power relations. In essence, the model is an upgraded version of body politic in which all members, human and non-human, are agents in a larger meta-body construction, an electronic as well as a biological body at once.

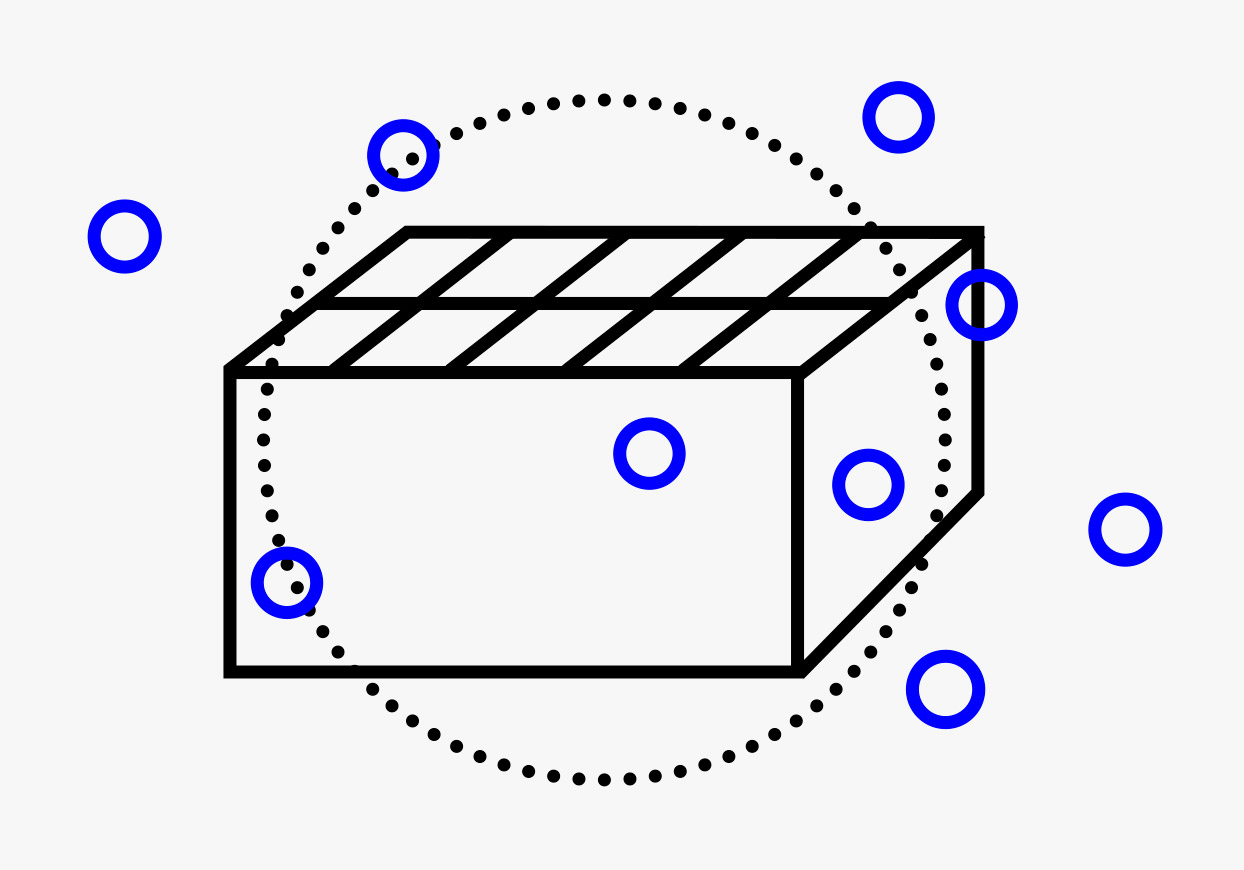

Present-day society has advanced to become a grid of identities wherein agents, according to their desires, are expected to integrate and take part in enacting the new state’s protocols. At the same time, and due to the open-source nature of today’s technological tools, the new state, however ubiquitous and infiltrating its mechanisms strive to become, is no longer a unique source of government. While it is the mainstream power network by default, it is being challenged by a multiplicity of alternative forces of various origins, all of which could fall under the term cyborg politics. This contemporary category of political resistance is activated via agents’ potential to transgress the grid and to drift freely.

Cyborg politics is a system of relations open to everyone – it is not assumed that participants need to plug into the grid or register with their local city council. The new kind of politics is dispersed, queer and based on affinities; it has no leaders; its members are no longer subject to disciplinary mechanisms, or any kind of sovereignty, or control apparatus of biopower alone. Cyborg politics fosters diversity and renders ideological constructions such as race, class and gender obsolete.

Here is a collection of notes for a lexicon, or rather a work in progress for one. It is a proposition for a vocabulary that would potentially enable a new discourse in parallel with mainstream ideology – and the narratives seamlessly co-opted within its domain, such as free speech, individuality and freedom of choice – if not completely emancipated from it.

Agent

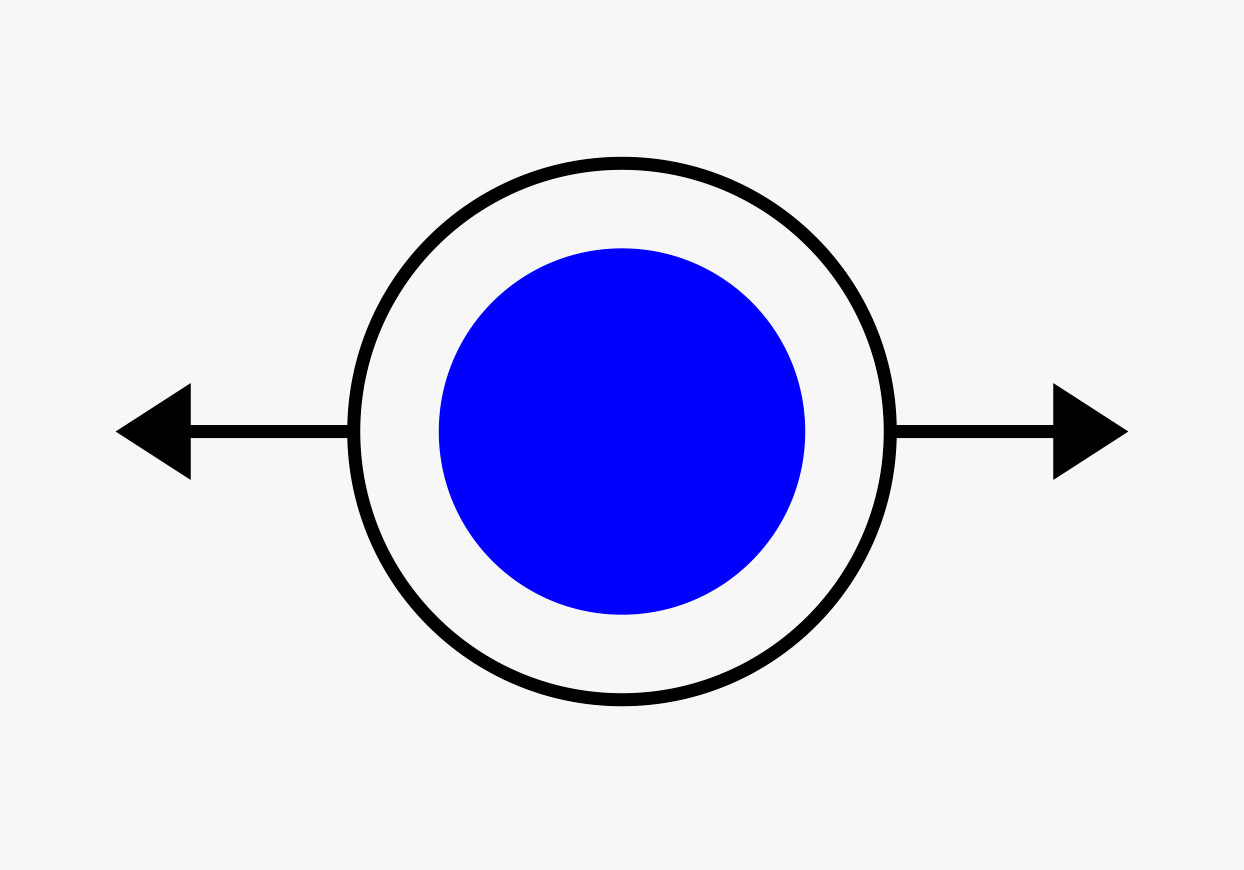

The central mechanism of the new state is the interaction of the multiplicity of its agents. Agents are the elements that make the new state operational and serve to foster the identities. They are essentially the members of society that employ their desires to activate their various identities, such as being a consumer, or holding a specific job, or providing care about their family members or other agents for the greater good. In this sense, agents are constitutionally different from machines that don’t have desires and are capable only of executing their specific jobs that can be automated.

Throughout history, various versions of agent software have been released, installed and become obsolete, making the agent a creature in a perpetual state of becoming. It is not about possessing certain physical attributes such as an erect posture, bipedal locomotion, manual dexterity or an oversized brain. Neither is it about the ability to form complex societies, nor being white or coming from a particular cultural background. Major and defining attributes for all agents are intellection and volition – ability for decision-making, complemented by the desire to use it.

Consumer

Consumer is an example of a popular identity of the agent: it is the motor, the beating heart of the new state. Consumer is activated via global factories, universal wish-fulfilment machines: agents keep supplying their desires to the grid, and it keeps turning them into more stuff. Modern protocols of exchange evolve based on access to statistics about what vast numbers of consumers want. This way the fulfilment of wishes can be automated and executed without delay, constructed and ideologically communicated from the get go. And it is not only about material ‘things’: global factories work the same way with the production of space, bodies, feelings, memories and desires. Did the new state’s regulatory mechanism ever want agents to help circulate surplus value in order to reinforce the operation of the grid and the protocols? Now it has access to knowledge that helps it to do so in a more direct way. Agents are required to desire not only the stuff they want in the first place, but also the stuff liked by others who desire the original item.

Cyborg Politics

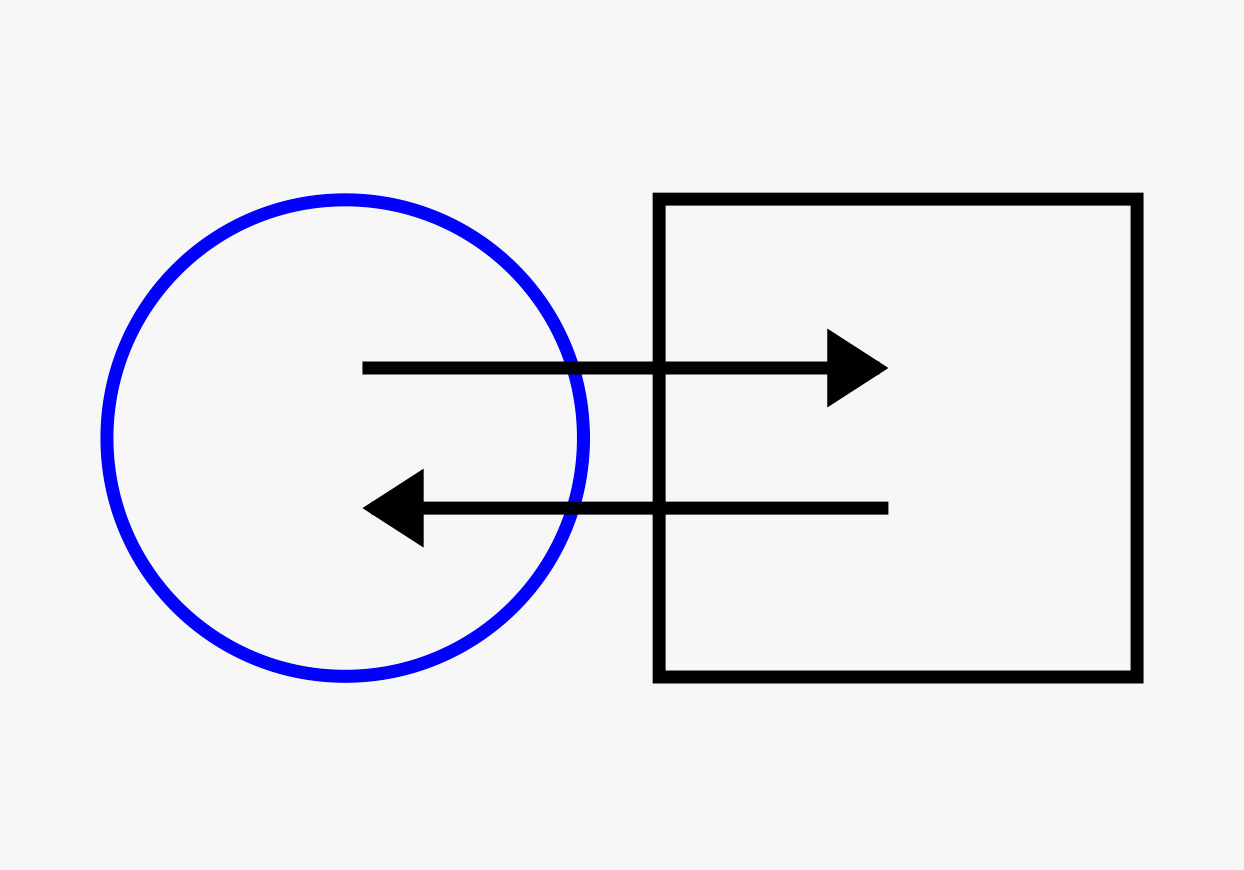

Cyborg politics is a category of guerrilla politics which act as resistance to the mechanism of the new state. It is empowered through the unique ability of networks to both create and dissolve power, to be secondary and dominant at the same time. The aim of cyborg politics is to critically re-examine the new state, its basis and its modes of working via repurposing the protocols, allowing the agents to be independent from the constraints of the grid and dismantling identities. It revisits the idea that the essential function of society, or the state, or whatever it is that must replace the state, is to take control of life and to manage it. Cyborg politics questions the identities regulated by the new state and, among other things, democracy’s presupposition that political communities can be based on geographical areas and that citizens can identify themselves with their nations and act together within those nations in view of that nation’s common good.

Cyborg politics is fundamentally different from other past critiques of the state. It is an umbrella term, signifying not one single political force, but a multiplicity of radically different movements standing for different ideas – all of which, to different extents, are dispersed and viral, and cannot be detected and addressed by the new state power. Cyborg politics therefore does not look to overtake the new state, but rather resist it, while its movements deny hierarchy and do not have distinct leaders. This form of resistance takes full advantage of the new state system, employs the agents that were capable of transgressing the grid and surviving outside of it, and uses technology, tools, machines and protocols for its own ends. While it is a parasite on the body of the mainstream state, it develops a multiplicity of alternative paths. Its value is that it is the only kind of resistance that can survive the new state without being subsumed and that has the potential to dismantle the grid, dissolve identities and return the independence to the agents. It is not based on the consumer-production cycle and therefore society’s healthier option with regard to maintaining the ecology and ethics. Despite its great potential, however, it needs further improvements. The main and crucial failure of such politics is that while its indeterminacy protects it from the mainstream ideology it attacks, its movements don’t have well-articulated agendas (such as the Occupies) or particular demands, and are thus vulnerable and often hijacked by other movements from within cyborg politics itself.

Desire

Desire is the base-level software an agent acquires at birth. It supports the agent’s basic functions, such as scheduling work, labour and other tasks and controlling identity-specific behaviours such as actions in public domain. Desire, as the main driving force, defines the aim of the agent’s existence and how to reach it; it aids in selecting the job, and is supported by a multiplicity of protocols, such as global factories and freedom. Desire is exclusive to agents and does not exist in machines and other tools, thus making agents unique players in enacting the protocols. All living beings possess some capacities, such as the capacities for growth and reproduction. The two main desires unique to agents, and the ones specifically communicated through the grid are to produce and consume.

Ethics

As a result of technological advance, thought processes became demystified, taken down to a mere function of the brain, essentially another tool. As a result it became obvious that there are other, technologically constructed tools capable of fulfilling this function much better than agents themselves ever could. Thus, the machine was assigned the function of making moral decisions – to the best of its technological capacity – and often the most complicated ones: imagine a situation where a self-driving vehicle has a choice to either hit a pedestrian, or swerve into a wall and kill the passenger. Who is that pedestrian? What if it is a member of the passenger’s family or a little kid? What if the pedestrian is a dangerous criminal? In the new state, the machine is ideally capable of generating and enforcing the answers to these questions, as well as other questions of ethics.

Food Conspiracy

Food is by far the largest part of the global economy. Despite the obvious dangers to the health of its agents and the environment, the new state mechanism, perhaps surprisingly, takes no interest in investments in this area. Sugar is one remarkable example of such delusions: this substance, which nutritionists believe is poisonous, is routinely added to food products to stimulate the sales. A similar market-driven conspiracy surrounds factory farming: animal agriculture makes a 40% greater contribution to global warming than all transportation in the world combined, and is proven to be the number one cause of climate change. But nevertheless, business in this area is running so successfully, that both mainstream ideology and most astonishingly, environmental organizations rarely turn against meat production.

Grid

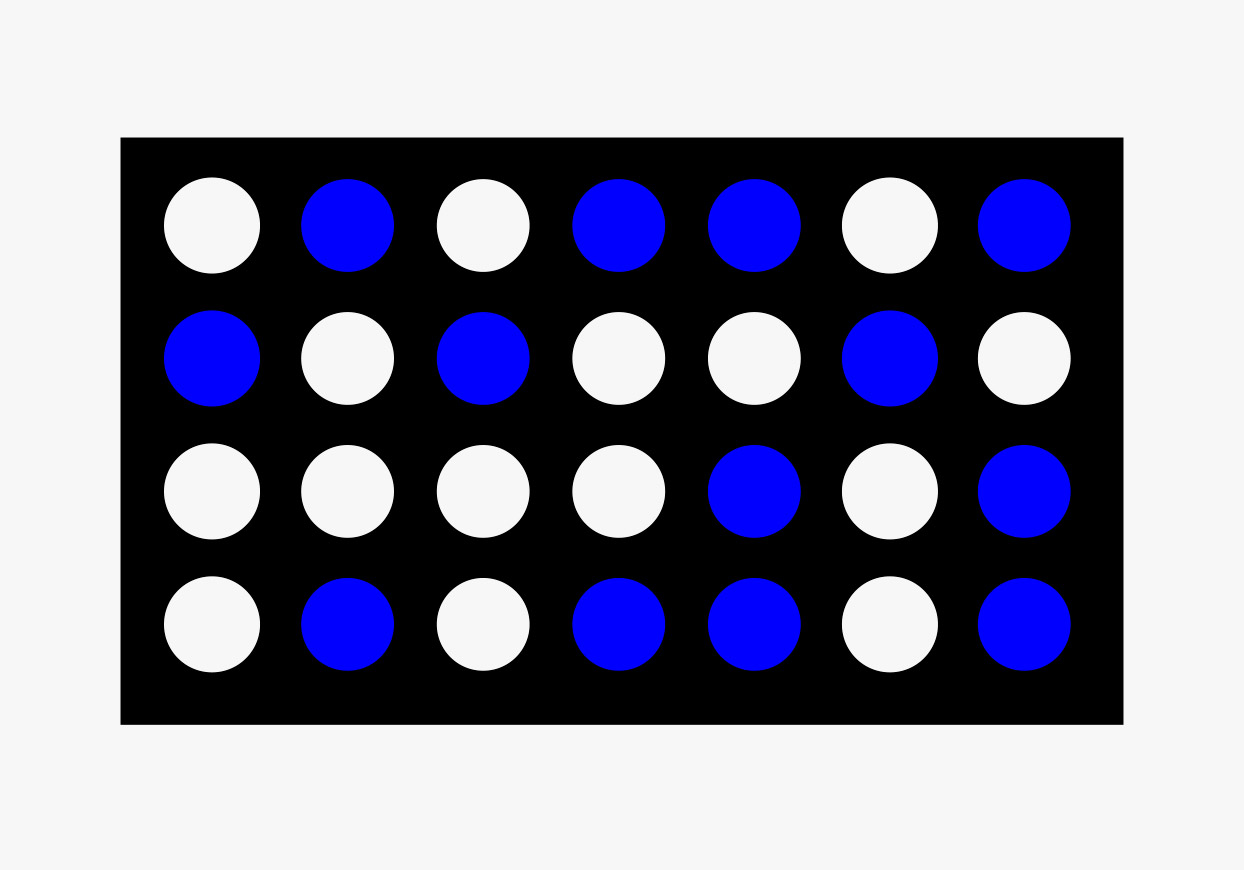

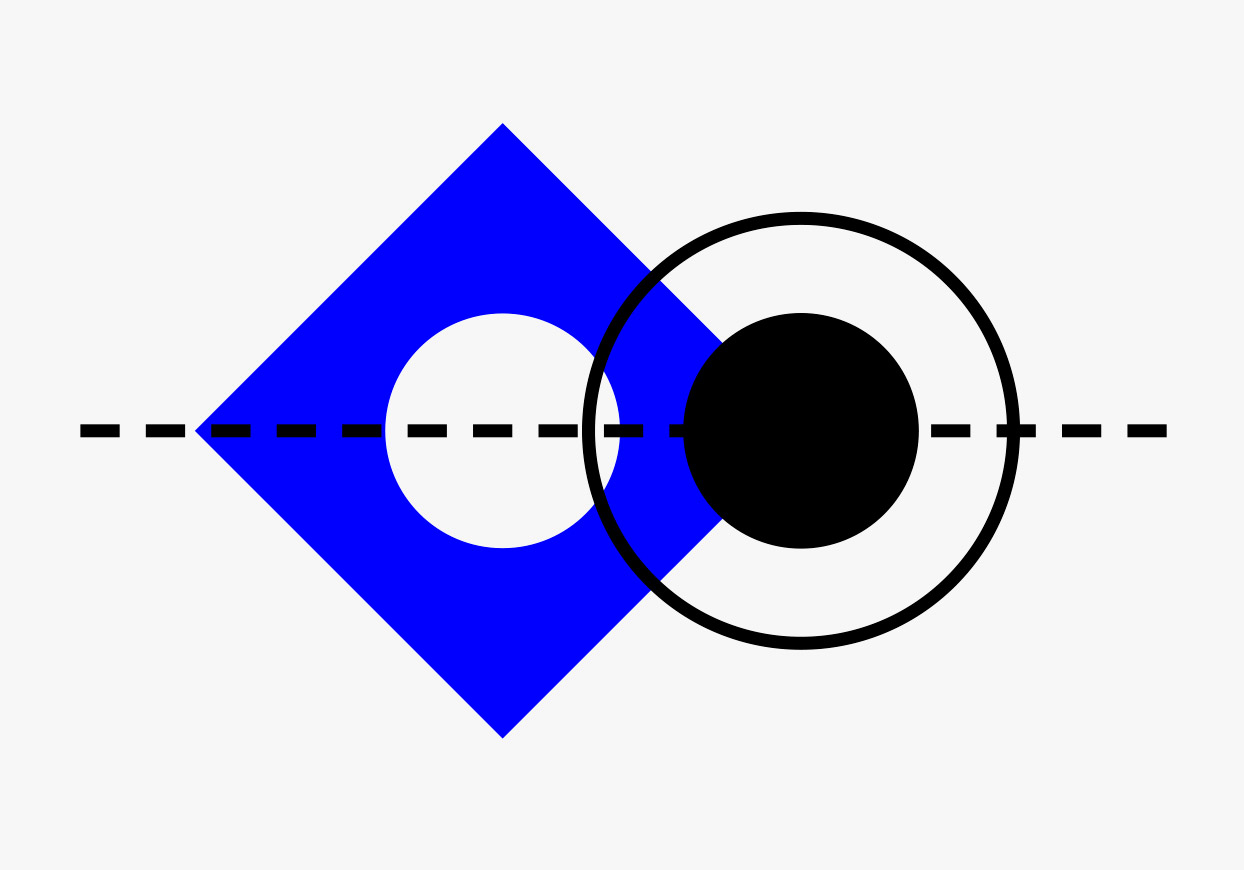

Grid is the container for identities, the syntax framework. The new state is by nature a source of semantics – its mechanism strives to get in the centre of all meanings and needs discipline and subordination from the elements it regulates.

Ideology is the grid’s main protocol, while means of its operation have been altered and upgraded throughout history. The new state power is invested in technological development up to the point when knowledge, technology and power merge together, enabling machines and agents to communicate directly, as any other data storages or CPUs do between one another. In this scenario, agents will no longer need external interfaces, such as laptops, smartphones or virtual reality devices, because they will be able to access everything through the grid directly. Their street maps, e-mail messages, social media activity, languages they need to speak, details of identities they need to associate themselves with, will all be provided by the authority in a most effective manner. In exchange for this, agents will surrender their own semantic ability, their mental contents, and personal data, which will then be stored remotely and communicated via the new state protocols. Cyborg politics, from its side, would benefit from such external access, and thereby is also interested in technological development, but argues that semantics need to be retained on the part of the agent.

Identity

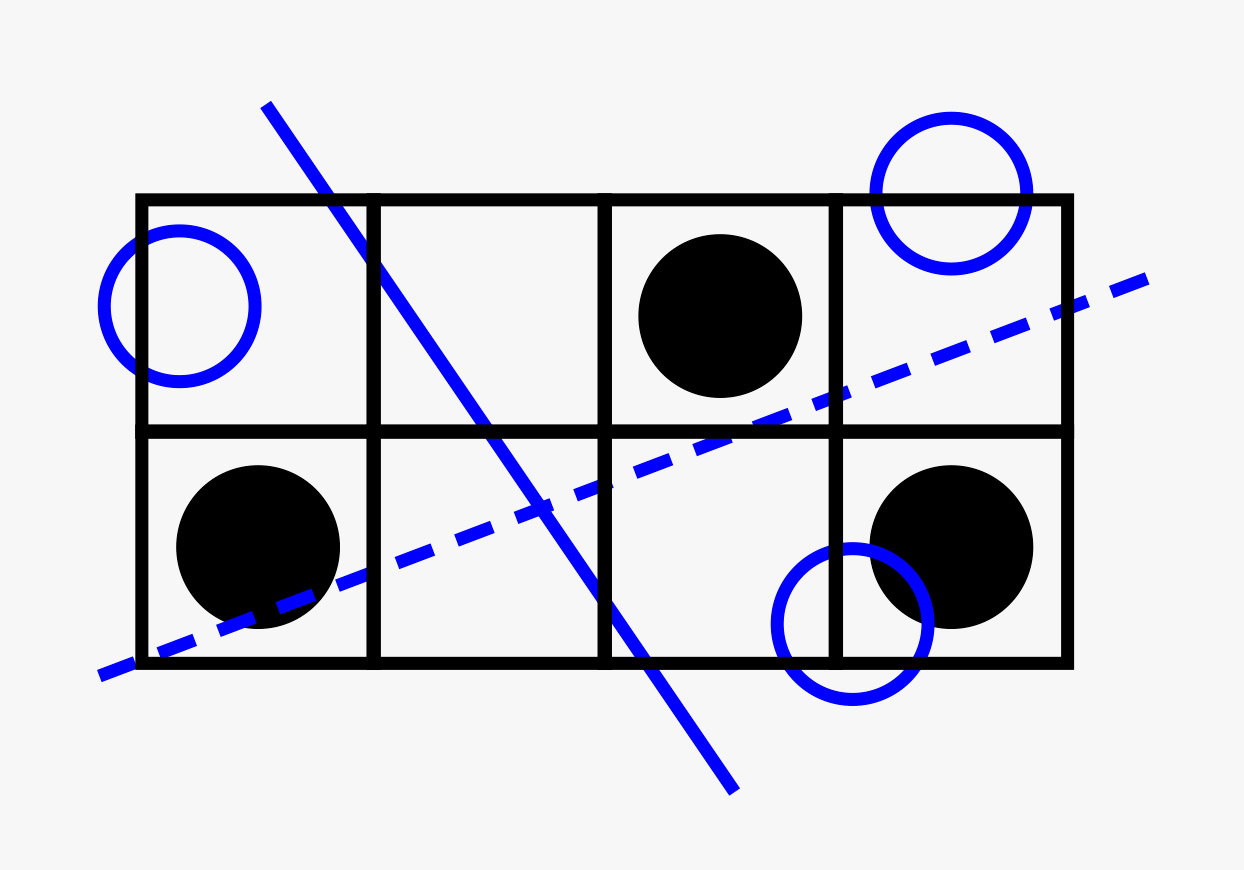

The basic condition of existence within the new state power network is identity. Each agent of the new state finds its place in the grid by identifying itself. Identities are communicated and learned through ideology as well as socialization, and while some of them are freely chosen, many are not comfortable. Language, culture, gender, race and class are all examples of identities. Identities are permanent – if the agent is situated within a certain culture, class or gender, it can only be operational while it sticks to it. Transgression is possible, but the price for breaking the identity is high – the agent loses its place within a grid, and it is extremely hard if not impossible to find a new place. Compare a historical mechanism of excommunication from the church: in the late Roman Empire, excommunication meant ‘civil death’ but left those who had lost their membership in the church full independence in all other respects. Due to the acquisition of this new independence, transgression of the grid is one of the vital requirements for cyborg politics.

Job

Job is an agent’s role within the grid, and is defined by the work the agent does. Work, one of three general protocols traditionally established within the biopolitical regulatory mechanism, is a project-based activity that has a beginning and an end and fabricates the enduring, public and common world of collective existence, while job is a market equivalent of the agent’s identity. Predominantly jobs are regular activities that are performed in exchange for payment. Boring and dangerous jobs are performed by machines; agents choose their jobs based on their desires and identities.

Two other protocols of the agent’s operation are labour and action. Unlike work, these two are not associated with any specific job. Labour is the agents’ self-maintenance, it corresponds to the techno- or bio-processes and other necessities of existence, while action is the agent’s capacity to take initiative. Although action does provide a semblance of freedom in decision-making, it is in fact limited to freedom within the grid, and only further binds the agents to their identities. Yet this limited freedom is crucial for correct functioning of the grid; deprived of it, agents rebel and become more independent; they loosen the ties with their identities, leave the grid and enter the territory of cyborg politics.

Leader

A movement without a leader is an important concept and a key to understanding the mechanism of cyborg politics and why it works in resistance to the new state. In the past, different models of state critiques were headed by a recognizable leader, a personality like Martin Luther King, Jr., Rudi Dutschke, Patrice Lumumba or Steven Biko. This has created a misconception that a movement without a leader will lose its force and fall apart, thus making such ‘head’ a target for those wishing to dismantle the movement. For example, the state would kill or imprison leaders or disarm them by co-opting and turning them into characterizations for mass media consumption.

But it’s not only the attacks from the outside that render the concept of a leader inoperative. There is pressure coming from inside the movements themselves. Apart from the fact that having a leader makes a movement an easy target for its adversaries, there is a structural issue: the concept of the leader is based on the deceitful idea that one person can represent opinions of many others, and thereby, among other things, justifies violence in the form of making its members execute decisions made by someone else. Models of ‘no leader movements’ as employed by members of various resistance groups including, but not limited to Occupy, Gezi Park, Tahrir Square or Puerta del Sol demonstrations among many others are examples of activities in the field of cyborg politics.

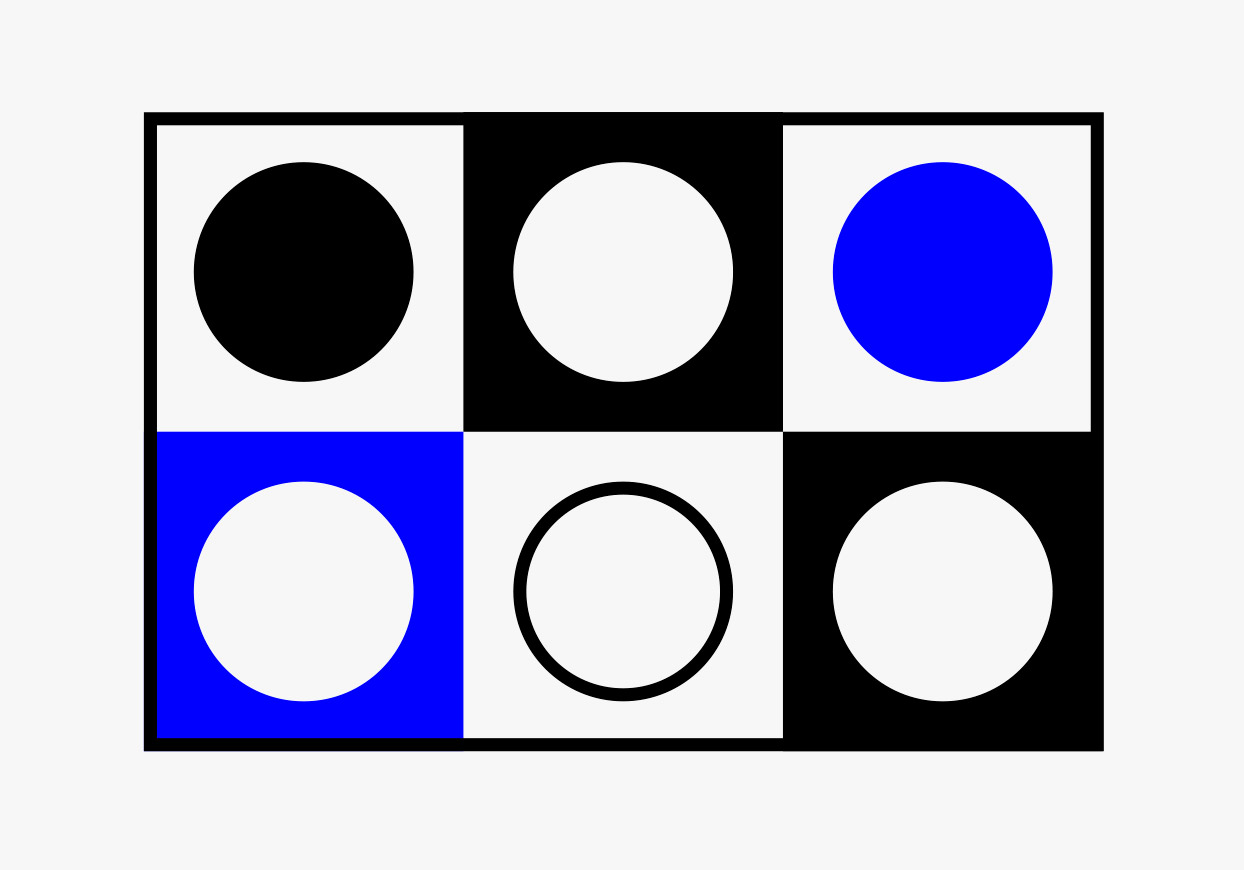

Machine

The tool has reached a stage at which it exceeds its original function and turns into a network of relationships – a machine. A machine, which is capable of educating itself and making its own decisions, is transforming the traditional notion of ownership of the means of production. In this situation it is no longer the owner of the tool alone that has full control, because the tool itself becomes empowered through access to knowledge. The contradiction between the new state and cyborg politics is that while the former still claims ownership of the tool and takes the most out of it, the latter sees it as open source and freely available.

A machine is a type of tool that has the ability to transcend its capacity for operation. It is the most popular complex tool employed by the new state power network in its hopes for the full automation of morals. The fact that a machine is the only non-agent capable of deciding on ethics is the rationale for why the new state mechanism is so invested in technological development to begin with. For example, Google’s DeepMind, a machine that is not only able to win a game based on pure logic like chess, but at Go, where the player is required to abstain from logic and rely on intuition. The new state regulation requires the machine to be ethical and communicate, represent and enforce these ethics.

Machines learn the agents’ behaviour and manage their identities to such an extent that in the new state’s ideal future they would be capable of replacing the agents, or at least of eliminating their mortality by recreating their virtual images. In this case, both the subjects of authority and its regulations could be switched on and off at any moment and for the first time in history the power would be neither the power to take life or let live, nor the power to foster life, but to ignore death by eradicating it.

Market

Unlike the job market transformation that has followed the European Industrial Revolution, the commercial arena in the new state era is evolving in a structurally different way. Operating on a very distinct scale of advancement, machines, doubling their power within 1.5 years and becoming 10 times more powerful every 5 years, transcend the traditional mechanization towards cognition. Increased productivity affects a much broader area of economy, and in a much more pervasive fashion than the steam engine.

As far as the job market is concerned, employment in routine intensive occupations declines as they become automated. While the new state power sees the work of a farmer, construction worker, receptionist, security guard and waiter as machinic, and endeavours to make them so, any roles that require interpersonal communication are resistant to automatization, especially in areas where motivating, nurturing, caring and comforting the agents is required. The other category is work that is naturally performed so much better by agents – like jobs of cooks, gardeners, repairmen, carpenters and dentists – that it makes automation unnecessary. Yet the new state regulation also recognizes that work is the indispensable means of tying agents to their identities, so new jobs keep on appearing regardless of how many of them are eliminated by automatization.

New State

Historically, power has evolved from the body politic metaphor based on sovereign right to biopolitics, where the agent’s natural life is included in political mechanisms and calculations. But while the present-day mode of government takes a lot from these models, it is on its way somewhere else. With the rise of many aspects of technology, power relations exceeded their limits, became pervasive, ubiquitous, and transformed into the new state, a novel political corporation. As any corporation, the new state power network is primarily engaged with managing its subordinate components, but also develops, among other things, biological and non-biological entities: agents and machines. At its base is a grid of identities, inhabited by agents driven by their desire to perform their functions, but essentially to produce and consume.

Much in the same way as the body politic’s sovereign acted as the artificial soul, giving life and purpose to the whole body state, the new state’s main protocols such as memory, equity and law benefit from wealth, concord and well-being and are confronted by sedition, sickness and death. The new state, as the updated electronic version of body politic, develops from a traditional government model that sees the state consisting of eight core elements: man, society, nation, monarch, political representation, legislation, administration, and social issues, but is now more complex and indirect. Man is being replaced by a wider and flexible notion of an agent, society has evolved into an overarching network, and the monarch is replaced by multiple entities, apart from political power also including such forces as global economic elites and mass media.

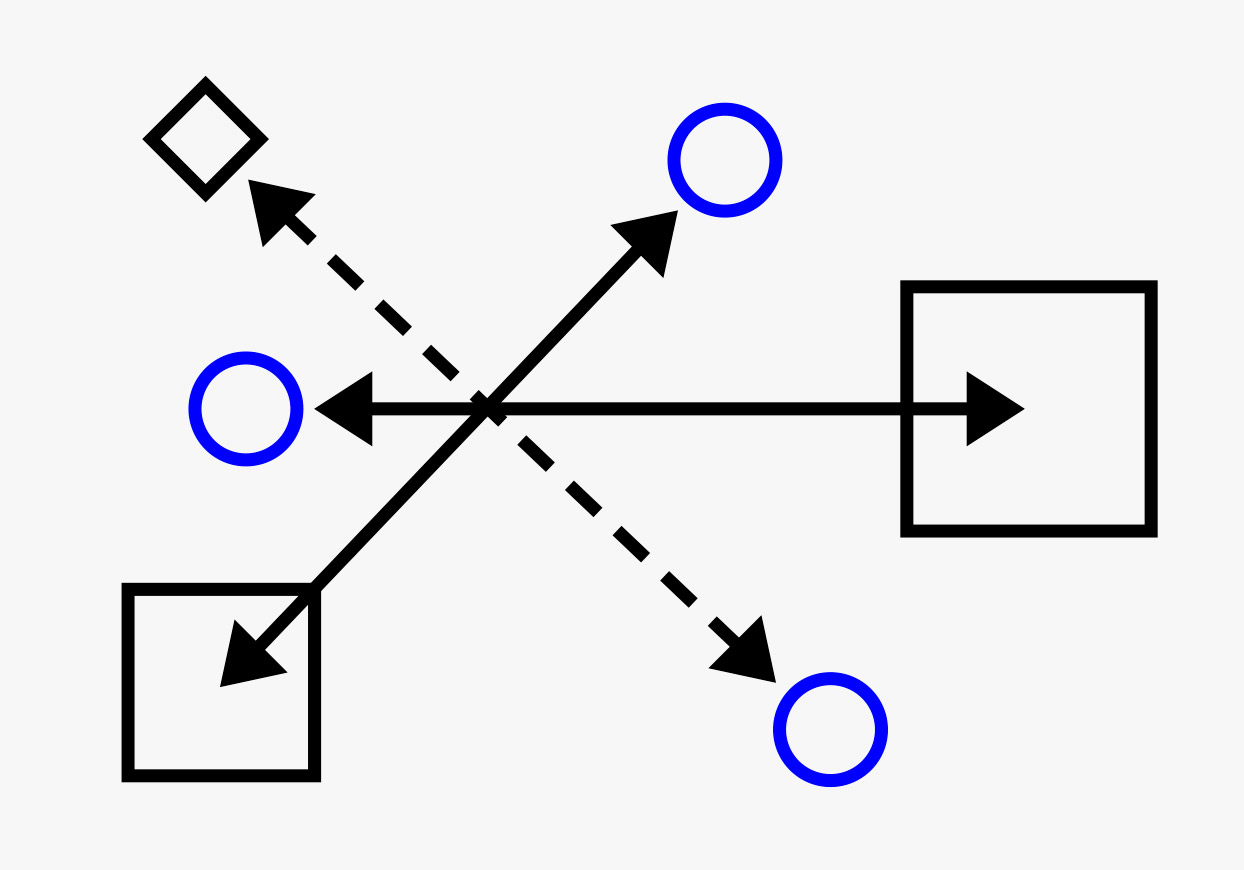

Protocol

Agents communicate among themselves, machines and the grid though a variety of protocols. Specific attributes are accessible via specific protocols, and each agent has access to many at once – protocols can be either disciplinary, coming from body politic or regulatory, originating from biopower. Some of the most important protocols are ideology, ethics, sexuality, law and death. By employing these protocols, the new state network is able to access the most specific agents and attributes in the most effective manner. Ideology, one of the core protocols, a collection of beliefs held by a group of agents, enables the authority to dynamically access various attributes of agents and regulate production and consumption, if not the markets, directly.

Different protocols apply for the areas of household and polis, private and public fields of agent operation. Within the household agents are bound by the protocol of labour for survival and self-maintenance, while in the polis, a public existence, agents have jobs and are involved in decision-making processes, activated through protocols of work and action.

Strong AI

Strong AI is the new state power’s hypothesis of a non-biological mind, essentially a machine brain that is smarter than an agent’s. Strong AI argues that the thinking process can be represented by a machine, because it is nothing more than a series of electric signals being fired into different areas of the brain, and that the machine can think in exactly the same way as agents do. If one of the biological brain’s neurons is replaced with an artificial one, the hypothesis holds that the subject will never tell the difference. Then another one is replaced, and another, and another one yet, until the critical mass is subsumed by the ongoing software updates regulated through the grid.

Tool

Although initially the tool emerged as the agent’s physical extension designed to perform a certain function, the relationship between the tool and the agent has always worked both ways: the agent created the tool and the tool, in turn, conditioned its creator. In the same way as the tool once played a decisive role in the transformation of politics from early primate state to discipline of the body and later ideological control, its effects are continuing as the technological development goes on.

References

- Timothy Campbell and Adam Sitze, ed., Biopolitics: A Reader (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013).

- David Cole, ‘The Chinese Room Argument,’ 9 April 2014, plato.stanford.edu.

- Francesca Ferrando, ‘Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations,’ Existenz 8, no. 2 (2013).

- Donna Haraway, ‘The Cyborg Manifesto,’ in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991).

- Michael Hardt, ‘The Leadership Problem,’ lecture, European Graduate School, 2014, www.youtube.com.

- Nick Heath, ‘Why AI could destroy more jobs than it creates, and how to save them,’ TechRepublic, 18 August 2014, www.techrepublic.com.

- Mark Kelly, ‘Michel Foucault,’ encyclopaedia entry, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu.

- John Markoff, ‘Should Your Driverless Car Hit a Pedestrian to Save Your Life?,’ 23 June 2016, www.nytimes.com.

- Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, ‘Automate Now? Robots, Jobs and Universal Basic Income A Public Debate,’ debate, University of the West of England: Social Science in the City, 9 December 2015, www.youtube.com.

- BBC News, ‘Will a robot take your job?,’ 11 September 2015, www.bbc.co.uk.

- John R. Searle, ‘Is the Brain’s Mind a Computer Program?,’ Scientific American 262, no. 1:31, academic.research.microsoft.com.

- C. B. Daring, J. Rogue, Deric Shannon, and Abbey Volcano, ed., Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and Desire (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2012).

- Kevin Timpe, ‘Free Will,’ encyclopaedia entry, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu.

- Majid Yar, ‘Hannah Arendt,’ encyclopaedia entry, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, iep.utm.edu.

Zhenia Vasiliev comes from a varied background, initially trained as a journalist and later as an illustrator. Despite having spent a big part of his career working as a print designer for book publishers and magazines, his current interest lies in the sphere of digital media, a field in which he now works as an illustrator and information designer. His work focuses mainly on data visualization and infographics, and more theoretically, on human-machine interaction in a post-human world.