Disobedient Images

Autonomia and the Politics of Representation

November 17, 2013essay,

Marco Scotini is the curator of the ongoing Disobedience Archive project, a video station and discussion platform that focuses on the relationship between artistic practices and political action. In this text, Scotini focuses on the Autonomia movement of 1977 and the Italian underground filmmaker Alberto Grifi, who is considered a cinema pioneer who anticipated contemporary disobedience cinema. Scotini analyses Grifi’s film Festival of the Young Proletariat at Parco Lambro and offers his reflections on social disobedience in relation to mediatisation and representation.

The contemporary forms of social mobilisation breaking out everywhere across the globalised space have some things in common: the refusal of representation, new ways of political visualisation and the experimentation with forms of organisation that deviate from modern political tradition, a tradition that delegates power to representatives of the people and social classes.

From the 1999 protests in Seattle to the recent demonstrations of the many international Occupy movements, from Zapatista uprisings to the Arab and Turkish insurrections, there is an identical transformative tension (global, chaotic, plural) that has never stopped to act.

The insurgent movements respond to the decline of the representative political model, the neoliberal economy’s new hegemony along with the governing police and military forces, with effective political experimentation that dislocates the classic methods of exercising power and resists the logics of representation (political leaders and parties, the ruling classes and the state).

In fact, one of the questions the mainstream media, analysts and opinion makers asked the various Occupy movements was: What are your specific demands? What are your demands that deal with issues such as public education, housing, justice, distribution of labour, etc.

As Judith Butler has noted, one implication seems very clear: The reason that there are “no demands”, whenever bodies assemble under the “Occupy” name, is that any list of demands would not exhaust the ideal of justice being demanded. Because “When bodies gather as they do to express their indignation and to enact their plural existence in public space, they are also making broader demands. They are demanding to be recognised and to be valued; they are exercising a right to appear and to exercise freedom; they are calling for a liveable life.1

Anyway, in the end we should also ask whom we are demanding answers from. We are currently facing the effective exhaustion of political representation and witnessing the transformation of social democracy into something else. We are all very well aware of the fact that most of the state’s resources have been by now completely privatised, thus creating a new and totally different centralisation of power and money.

So the problem is not so much that politicians are corrupt (even if in many cases this is also true) but rather that the constitutional structure isolates the mechanisms of political decision making from the powers and desires of the multitude. Any real process of democratisation in our societies must attack the lack of representation and the false pretenses of representation at the core of a nation’s constitution.

We are not dealing here with a moral issue of trying to hold constitutional power accountable to its duties. Instead, we are facing a politicised space. We should thus recognise and acknowledge that we are dealing with a real discontinuity with respect to the liberal tradition and its reformist tendencies. We are now facing a political horizon that has no centres and peripheries, and cannot be analysed through the lenses and paradigms of good politics and good art.

The current NO, the refusal to obey of contemporary dissent, does not propose a dialectic position in relation to power, instead, it establishes itself as a force of creativity and experimentation: of languages, activities and subjectivities. The space to which they are exposed is that of the new imaginaries and new opportunities of life that reveal as many aesthetic models as there are productive forces and social movements.

As sociologist Maurizio Lazzarato recently affirmed one thing is really clear now – “there are no alternatives possible within representative democracy.”2

The contemporary “financial crisis” is not solely an economic crisis, but also a crisis of neoliberal governance, whose wish to make every individual an owner, an enterprise, a stockholder, failed miserably with the collapse of the American financial system. This economic failure and that of the failure in the production of subjective images of the owner, stockholder, and entrepreneur go hand-in-hand.

The subjectivities produced by the neoliberal economy and its crisis today are exactly that social terrain in which and against which the insurgent movements and movements of resistance have to act. These movements not only have the capacity to reject these subjectifications, but they also hold the creative capacity to bring to the fore new forms of life that all share a common matrix (communisation).

What, then, are the necessary conditions for a political and existential break at a historical moment when the production of subjectivity constitutes the first and most important form of capitalist production? What specific instruments of the production of subjectivity are needed to obstruct its industrial mass production by business and the state? What forms of organisation should be created for a process of subjectification that would make it possible to escape both the grip of subjection and that of enslavement?

In fact, the refusal of representation as a final stance is the refusal to delegate the organisation of “what divides us (property, wealth, power) to political parties and labour unions, and the representation of what we share (citizenship, community) to the State”.3 This dissent has its origin in a new concept of political action that first came to the fore during the 1970s revolution.

One of the historic examples that I have used for years as a working model derives from the experience of the Autonomia movement in Italy, which was brutally interrupted by the big trial of April 7, 1979. So, rather than focusing only on current events, I think it is necessary to analyse some of the anticipations of our present in recent history because those are our effective contemporary potentialities.

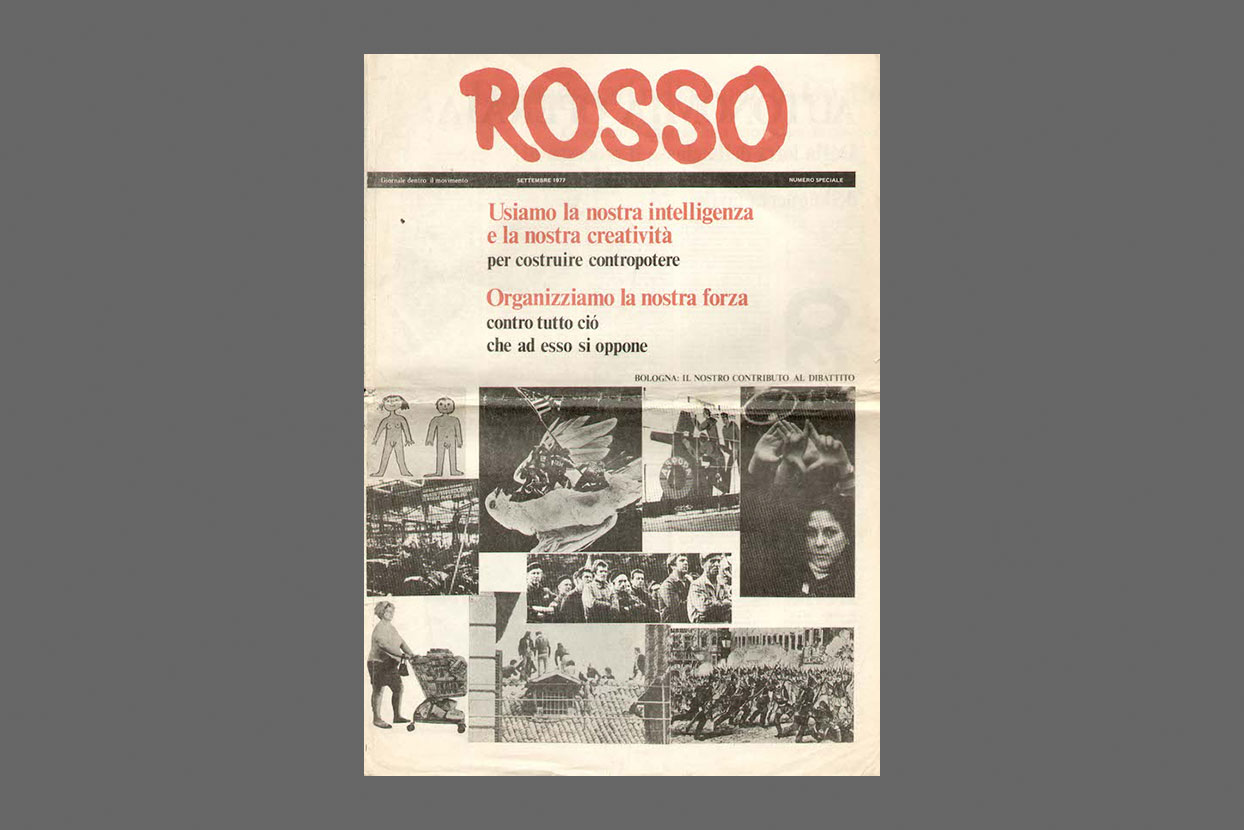

Autonomia is, in fact, a really important example in that it anticipated the radical or absolute democracy that locates itself outside of the idea of representation allowing it to create a new form of visualisation of contemporary politics.

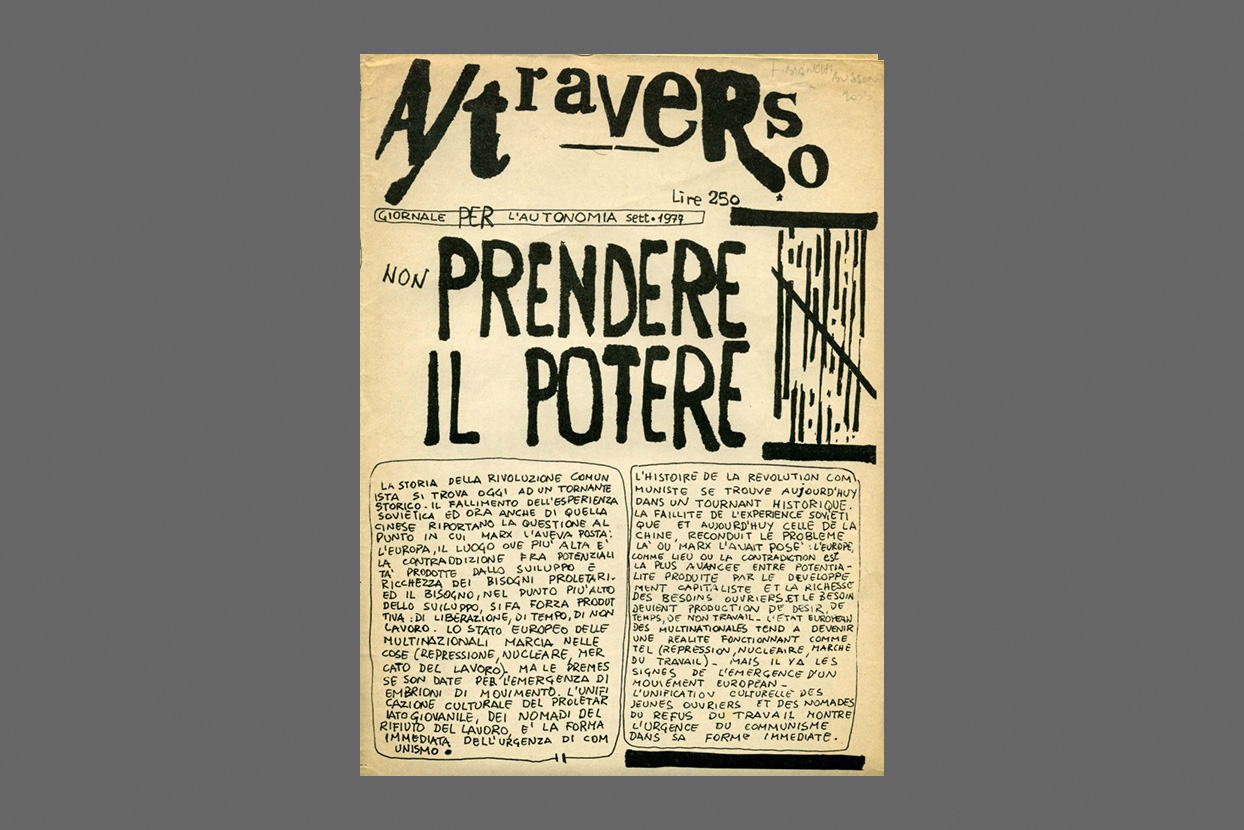

The history of Autonomia consists of a multiplicity of diverse political experiences during the 1970s and whose identity revolves around some powerful ideas such as: “class composition”, “dispersed factory”, “refusal to work”, the shift from the “mass worker” to the “social worker”, a politics of personal life, etc. Autonomia is about raising the awareness of a series of problems and about approaches more than solutions. Furthermore, it is about acknowledging the emergence of urgent needs that are no longer confined to the factory, in other words, the formation of the social and political autonomy of the new revolutionary subject.

By the end of the 1970s, Autonomia had completed its first cycle of struggles. It later re-emerged at the beginning of 2000 as an antagonistic theoretical force, first within the framework of Post-Fordism and currently under the system of biocapitalism. This militant debate had its effect on the last decade and accompanied the protests against capitalist globalisation, which is today focused on the fight against the current financial crisis and the public debt.

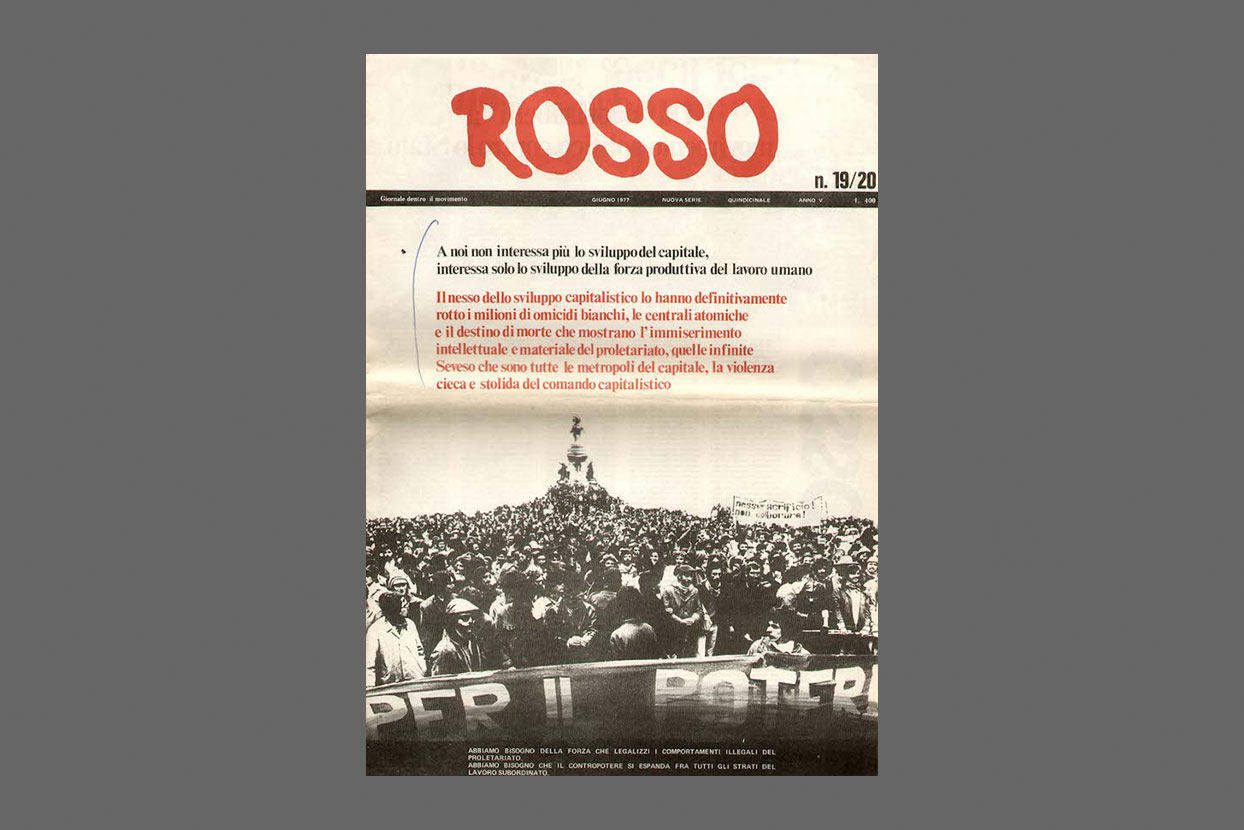

The first problem concerns forms of antagonistic organisation inside the factory. Through the criticism of the trade unions it found one of the starting points of an emergent consciousness characterised by a new movement toward the self-organisation of the workforce. However, this is not simply about a timely and systematic disapproval of the role of mediation carried out by trade unions with regard to the specific points of contractual negotiations with the bosses. For Autonomia, it is clear that the trade unions are an inner institute of capitalist dynamics and, therefore, an instrument for negotiating the selling price of the workforce. Here the new, avant-garde forms of organising labour begin to emerge not only outside the trade union movement, but mainly as an alternative to it, developing a radical and destructive criticism of trade unionism. At the same time, the concept of “class composition” has radically shifted the focus of the working class to one of social self-composition in which the different cultural, political, and imaginary elements produced by social work merge. As Toni Negri asserts: “With the end of Potere Operaio (Workers’ Power) movement, the origin of the councils and the crisis of organised political groups, the first autonomous assemblies emerged in the factories.”4

The major incentive for their birth came not only from a complex series of political issues that emerged within the framework of the struggles, but more specifically from the Fiat factory conflict of 1972–1973, which gave rise to the complex political grouping of workers known as the Mirafiori Party. The activity of the autonomous labour assemblies spread rapidly from Turin, as the movement made contact with emerging political student groups and autonomous collectives that were being established in many of the proletarian areas of towns and cities, giving life to a large and informal network of social struggles in schools and factories that, due to the groupings involved and their composition, can be identified as the birth of the Autonomous Zone.5

It took five more years before the fateful 1977, when the movement reached its culmination, having effectively disseminated its notions of autonomous behaviour en masse. If, in the 1960s, “labour autonomy” (autonomia operaia) was an expression initially related to forms of contractualism and trade unionism, by 1973, the expression began to mean something different, something larger. The struggle for self-organisation transcended trade union control and a prescribed political logic. The events in the Mirafiori district of Turin in 1973, spawned new, more radical, meanings of the expression “autonomia operaia”. It came to mean that workers and the supportive proletarian community, could establish their own social terms of exchange, production, and cohabitation, independent of the state justice. Autonomous of the laws that governed shifts, working hours, and private ownership. The autonomy principle now acquired its full etymological meaning: proletarian society defines its own laws even in a region that was under the state’s military occupation.

These notions and the experience regarding Autonomia eventually led to the creation of my curatorial project in 2004, as I became ever-more conscious of an emerging alliance between art and activism. The Disobedience Archive is an itinerant and expanding video library without a defined shape, and serves as more of a counter device or a toolbox that can be utilised rather than just serving as a collection to be exhibited.6

The Disobedience project evolved on the back of the strategies that were called into play by the “movement of movements”, but also came in the same year that a certain version of the movement appears to have ended. The Disobedience Archive intends to be an atlas that covers various contemporary resistance tactics from direct action to counter-information, from constituent practices to forms of bio-resistance. As an archive of heterogeneous and ever-evolving video images, the project aims to serve as a user’s guide of the histories and geographies of social disobedience: from the Italian workers struggles of 1977 to global protests, before and after Seattle through to the current insurrections in the Middle East and the Arab world. The Disobedience project is an investigation into the practices of artistic activism that emerged after the end of Modernism, inaugurating new ways of being, saying and doing. A different kind of relationship between art and politics characterises the current phase of biocapitalism in which it is impossible to understand society’s radical changes other than through the transformation of the languages it produces and has produced as both political subject and mediatised object.

In fact, the Disobedience Archive situates itself on that social terrain, which is located at the core of the production of subjectivity. To be more precise: the archive derives from the consciousness of contemporary subjectivities as mediatised subjectivities.7

In the age of mediatisation, the production process of subjectivity is organised by technological tools in the same way as material production processes are, so that there is no longer any separation between the flow of signs and flows of materials or forces. According to Lazzarato, this is because signs extend into the real and vice-versa.8

This condition is well known to both Felix Guattari with his concept of capital as a “semiotic operator” and Guy Debord with his concept of the “spectacular”. Both integrated their Marxist analysis of capitalist exploitation by extending it from the expropriation of productive activity (labour) to the expropriation of language and signs (communication, life, etc.).

That is why mediatisation today serves as one of the main factors in the growing indistinction of the division between life and work. The Disobedience project collects these fragments of political subjectification, which, in turn, produce new forms of enunciation and transforms those forms into a decisive praxis for an insurgent project.

The role of the Disobedience Archive (of its constituent video and film images) also includes revealing the mediatised nature of history. On the one hand, it aims to reveal precisely what the corporate media, as the central agents of political authoritarianism, attempt to conceal or removes from sight. On the other hand, it aims to take back control of the violent expropriation of experience, and, in turn, ends up producing history and rendering it visible. History, which is often considered a problem of representational politics, is at the centre of these films and videos that range from documentaries to counter-information, from film essays to agit-prop cinema, from video activism to grassroots community cinema. This Disobedient cinema (the multiplicity of its forms) enacts a strategy of action that runs throughout the canonical divisions established by the “power” such as the environment, bodies, psyches, work, society and semiotic flows, in order to intervene in life as such. The Disobedience Archive is not only a sample of struggles and protests but rather an archive of imaginaries, of ways of living, of production, of looking, of learning and self-representation.

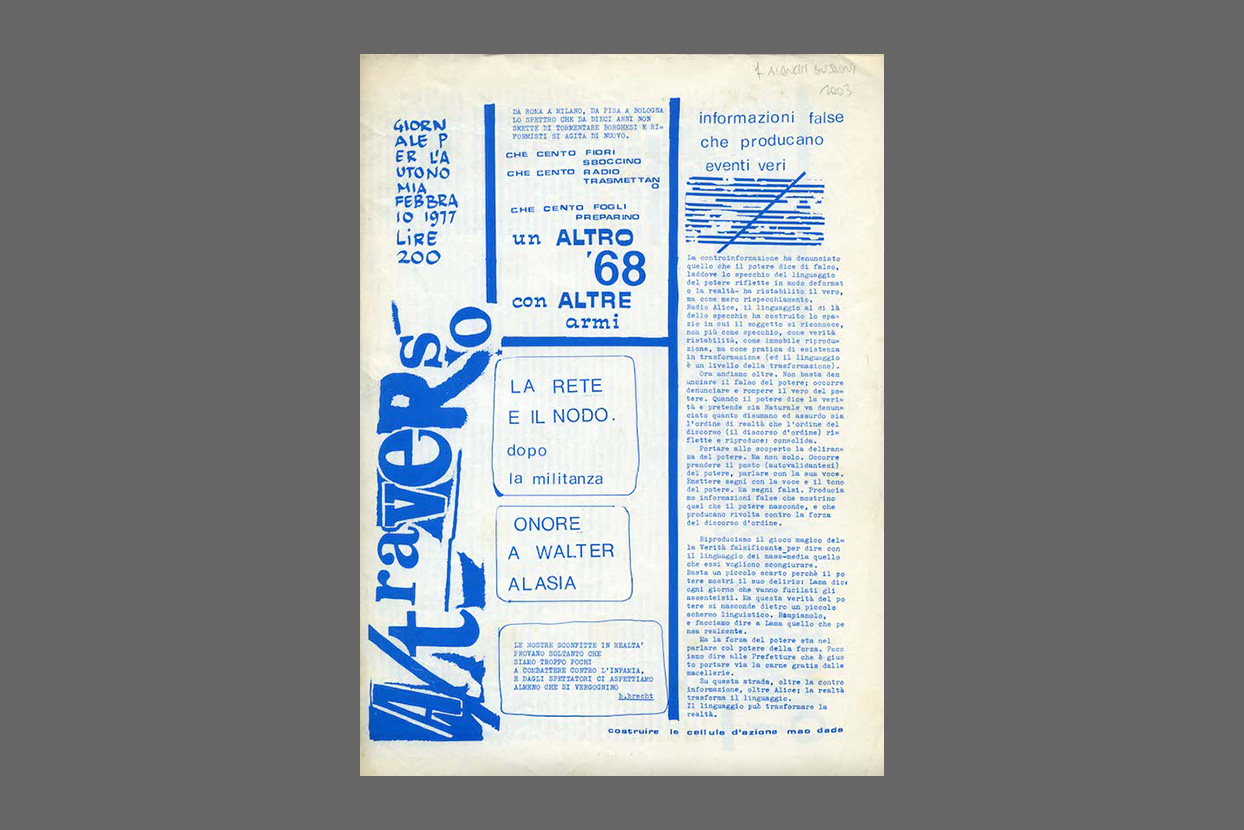

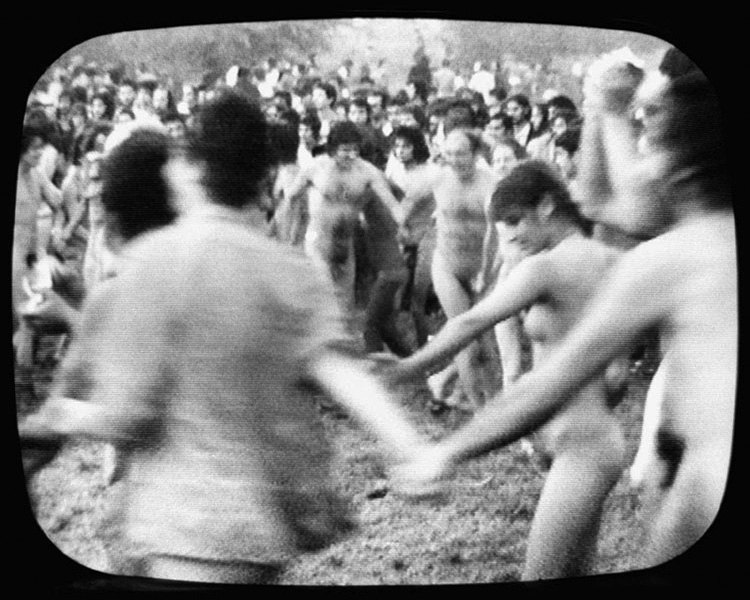

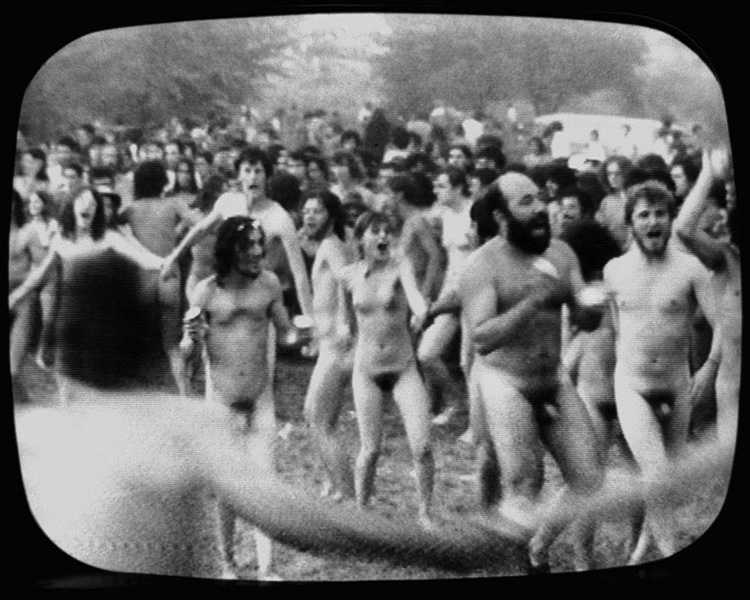

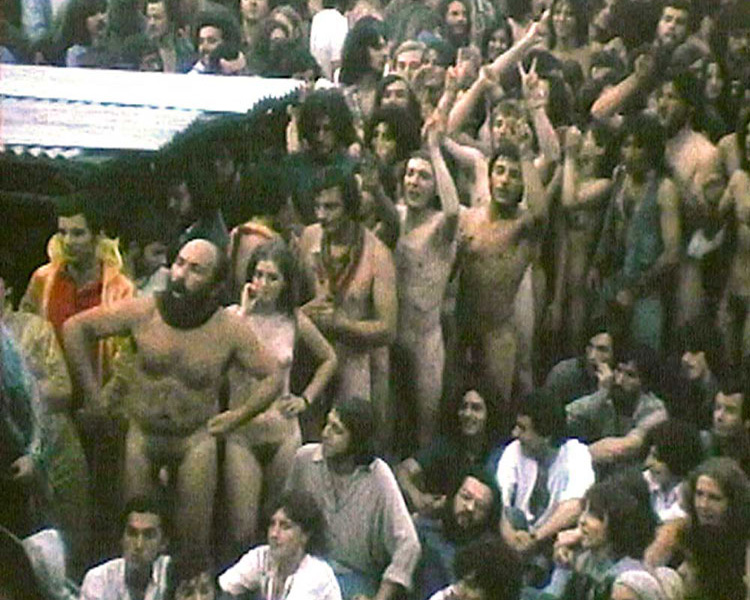

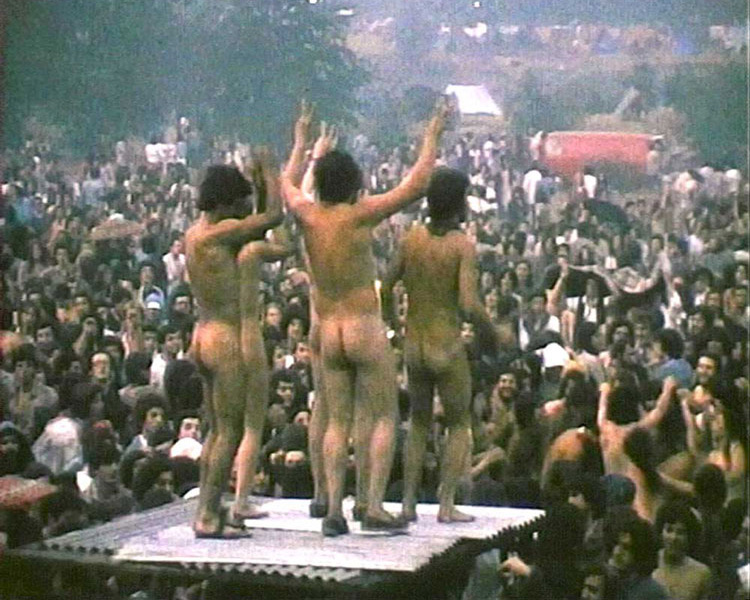

The Italian movement of 1977, with which the Archive commences, is not only a political anticipation with regard to social disobedience but also of corresponding mediatisation. The main representative of this relation is the Italian activist and filmmaker Alberto Grifi who, at the Parco Lambro in Milan, filmed the disobedience of thousands of youngsters and, in doing so, refused his defined role as a film director whose task is to simply record and bear witness.

But what was the nature of this Parco Lambro event? In one of the 20 letters in Toni Negri’s book Pipeline, written while in Rebibbia Prison, he wrote: “Dear David, if you had been passing through Milan in the June of 1976, you would have found it hard to avoid Parco Lambro. On the contrary, I am sure you would have made a beeline for it. ”9 From 26 to 30 June 1976, Parco Lambro was transformed from a counter-cultural and musical happening into an impressive political event. In those four days, the very original nature of this gathering was forever altered.

In this sense, the way that Alberto Grifi, an artist and Italian cinema outsider, expressed himself as a filmmaker remain exemplary. Grifi arrived to record the Parco Lambro event as a pioneer of underground cinema and emerged as the major exponent of video-activism and counter-information. In recording this protest as it was happening, the act of documenting, for Grifi, was transformed into an activist strategy.

Grifi arrived at Parco Lambro in June of 1976, with four crews of video hooligans and three crews of cinematographers. But who were these “video hooligans” (videoteppisti)? Grifi’s collaborators described themselves using this term, which immediately indicates the movement area of provenance. The term, which became fashionable after the mid-1970s, is a perfect play on words that combines the technical recording device (camera and videotape) and the vandalistic nature of the actions in which it becomes involved. As Flavio Vida (one of Grifi’s collaborators during the Lambro period) recently said, this all had more to do with derisory situational experience than with any real form of left-wing militancy. What portable video cameras allowed the artistic and activist collectives to do in the 1970s was offer them the potential to become directly involved in the interventions that included street demonstrations, public square actions, etc. with the recording of images and sounds on magnetic tape that was dramatically less expensive than 16mm film. The official organisers did not want official state television documenting this sixth edition of the Festival and chose the underground filmmaker Alberto Grifi instead. He’s a director you might expect to produce a music documentary in the style of Monterey Pop, which remains an extraordinary 1967 documentary filmed by two protagonists of direct cinema, Donn Alan Pennebaker and Richard Leacock and in which the artistic avant-garde converged with the social avant-garde.

But what Grifi ended up documenting did not turn out to be some peaceful pop festival with an audience watching rock stars on a stage. Instead, he ended up recording an authentic proletarian “expropriation” (as they were called back then). Expropriation means “deprivation of property”, which entailed seizing supermarkets, occupying houses, refusing to pay for concert tickets, demanding political prices, the self-reduction of cinema ticket prices, for instance, is characteristic of the actions of the young proletarian groups from the mid-1970s.

The more than one hundred thousand young people who came to the Parco Lambro from all over Italy did not simply stand around idly watching the musicians on stage, but actually overran the stage and took it over as they protested against music as commerce that was consumed no differently than other kinds of merchandise such as sandwiches, chicken, beer, ice cream, books, or records) that the organisers expected to sell. In the heat of the moment, they managed to expropriate the merchandise and services and redistributed them freely to all as common goods.

The public had rejected its role as a consuming audience and refused to act out the role assigned to them at this festival and instead became the main protagonists. The way the audience assembled and engaged in a collective dance (comparable to the pagan rites of antiquity, as Grifi observed) was their way of fighting against the entire profit-making concert format and its conventional hierarchies and business-dominated organisational structure.

Grifi never had any specific film plans for Parco Lambro, and his main problem entailed trying to figure out how to tackle this unknown terrain (that of the event) with a certain type of technology. If Grifi was actually forced to confront an insubordinate and transforming sociality, how could he suspend the predominant codes of filmmaking valid till now? How could he neutralise assignments and destroy the identities that cannot be anymore solely attributable by means of a recording device? How could he record an event in real time – something that by its nature refuses to be captured and whose outcome cannot be foreseen?

The result was the extraordinary film Parco Lambro10, which was not only a unique visual document of those specific years but many other films at one and the same time (and possibly not even a film in the conventional sense). There are many versions of this film with different edits and lengths for different target audiences and different distribution circuits. The versions vary from a five-hour edit to one that was no more than a half an hour long. There was never a definitive or director’s cut. So it remains accurate to describe the film as 27 hours of video-recorded black-and-white tapes and three hours of colour 16mm film.

This is not the only reason why Parco Lambro continues to be many films in one: it is a multiple film. The other, equally fundamental, reason is that Grifi transformed the recording process into a counter-investigation torn from the hands of journalists and directly redistributed to the very subjects of the events. The camera thus passed from hand to hand, turning everyone into protagonists and the act of recording into that of direct intervention. As Grifi has claimed (and it is clear from the filming): “the groups did not passively film what was going on…. Often those [doing the] interviewing were even angrier than those [being] interviewed and it was they who gave directions to that flow of sub-proletariat illegality”.11

What we have, then, is not a film that is participated in as is the case with cinema verité, which usually involves the cinematographer in the film itself, in accordance with established documentary models from Rousch to Leacock, etc. Instead, we have an act of radical disobedience that destroys directorial conditions and the authoritarianism of the filming itself.

The making of Parco Lambro led to the discovery that a cinematic troupe can no longer be simply manufactured by the producer, not unlike how the owner assembles the workers, but must instead be dictated by the precipitation of events and happenstance. This is what allows Parco Lambro to produce new subjectivities that are no longer purely political or militant but more characteristically disobedient. In her essay The Articulation of Protest (which has generated a lot of debate because it was first published during the years of the Antiglobalization movement)12, Hito Steyerl identifies two methods for articulating the representation of the movement’s revolt and the organisation of the protest movements, two methods that pass through editing: One is represented by Showdown in Seattle, which was edited by hundreds of media activists (creating a broad montage of voices, which ultimately represents the voice of the people) and the other is Ici et Ailleurs by Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Mieville in which the filmmakers address the same problem of the addition of images, not one after another, but one next to the other. Grifi presents something else that, irrespective of the other artists, opens up to forms of self-representation and unedited self-organisation. Grifi presents new ways of engaging in and expressing politics.

One of the reasons why Grifi has never managed to come up with a final edit of Parco Lambro is that he basically realises that the new political subject cannot be recomposed. In 2004, upon my request for a copy for the Disobedience Archive, he sent yet another version (90 mins.) with an introduction where he discusses the restoration of the film that I was unable to include in the Disobedience Archive. His removal of the single, definitive copy is something akin to removing the exclusive social subject, the people. In this sense, we can neither comprehend Parco Lambro following the criteria set by Umberto Eco for his concept of open work (“opera aperta”) nor for its combinatory possibilities. Parco Lambro is the first film that does not converge, it is the first film that does not close, that keeps the recorded material to itself. As a consequence, we can consider it as the origin of the proliferation of the contemporary multitude, in the same way Toni Negri read the Parco Lambro event.

In this sense, Parco Lambro is a radical anticipation of contemporary disobedient cinema that presents itself as a new way of engaging in and expressing politics. It focuses attention on both the forms of production (group work, financing, technological media, target audiences) and on distribution (parallel circuits, projection strategies, innovative channels). It also concentrates on the circulation speed of the images, on the contexts of locally specific reception and on the role of the spectator or consumer rather than on the image as a place of mediation or on the power of the image as such (on its semantic innocence or guilt). The area occupied by the image within current audio-visual capitalism represents a sort of defence of capital. It is the area of interdiction for other images, a strategic space that distracts attention from the rest.

Independent of what it demonstrates or censures, the displayed image is also, and above all, that which conceals all the others. The new web archives posted by Arab media activists are a direct counter-expression of this, as a member of the Egyptian Mosireen collective noted: “Everyone now is a filmmaker. Our revolution must be among the most recorded events of all time. The gap between the classical, expensive production process and the availability of daily life is being ever more tightly bridged. Every mobile phone now has the power to challenge, to become the narrative. This disruptive decentralisation of the news, the occasional eruption of civilian participation, has happened also many times before”.13

The Disobedience Archive consists of video material that covers gentrification, grassroots planning, bio-diversity, alternative economies, new communities, control, social disobedience and protests, artist products and activists as both political subjects and mediatic objects. The lack of acceptance of political representation in favour of situational action, the clear rejection of delegation to political or media representatives, the invention of alternative distribution circuits, the rejection of a-critical notions of documentaries in both form and method, are at the centre of new action programs that promote new political subjectivities.

These groups promote the processes of autonomous and collective planning for real places and, at the same time, they are the producers of urban images that exist beyond dialectic or classical protest forms that involve antagonism, sometimes avoiding trench warfare with the powers that be but, conversely, developing parallel, interdisciplinary universes from a daily and “ground-up” perspective. In order to create dissent and resistance to the new forms of biocapitalism, they act transversally to cross through the whole of life itself. This is very different from militant cinema images that contain the intelligence of the movement, foreseeing its choices and claiming legitimacy of the correct interpretation of the forms of power. These new images, on the contrary, are both committed and simultaneously removed, denying habits, imitations, the definitions that codify and reify political spaces. They act as devices of profanation and claim an experimental potential with respect to political directions or commands. They map out the politics of immanence, never given once and for all, but as something that is consistently conquered via the pragmatics of experience. We still do not have a good name for the images of this film: how about “disobedient images”?

The most important notion of the Disobedience Archive is that it represents an attempt to create a grammar of the new forms of political action globally, which may help us transpose our molecular revolutions to the area of macropolitics.

Parco Lambro was a significant blow of a unique sort, not in the field of work (the factory and material production), but in amongst consumerism, the audience and the public.

But the question remains: What kinds of tools can we find and use today that would be as effective as the strike was for industrial society?

This text is based on a lecture held at Stroom Den Haag on September 29, 2013. It is the final result of a research which was presented at different stages in the form of a lecture at steirische herbst, Graz, 2012 with the title Thinking Politics Freed From the State: Autonomia for Example, and at Kadist Art Foundation, Paris 2012, with the title Cinéma Politique. Alberto Grifi, Antagonistic Cinematography and Work-force.

1. Butler, J., From and Against Precarity, www.occupytheory.org, accessed 15 October 2013.

2. Lazzarato, M., “Disobedience and Political Subjectification in the Present Crisis”, in: Scotini, M. (ed.) Disobedience Archive. (The Parliament) , (Bildmeuseet, Umea, Sweden: Archive Books Berlin, 2012) 19.

3. Ibid.

4. Toni Negri, cited in Scotini, M., Autonomy, in: Baladran, Z., Havranek, V. (eds), Atlas of Transformation (Zurich: JP Ringier, 2010) 70.

5. See Balestrini, N., L’orda d’oro, (Milano: Feltrinelli, 2003) and Lotringer, S., and Marazzi, C., Autonomia: Post-Political Politics, (New York: Semiotext(e), 2007.

6. Since its inception in 2005 in Berlin at Kunstraum Kreuzberg / Bethanien, the project was presented every time in different formats in institutions such as: Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven), Nottingham Contemporary, Raven Row (London), the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Boston), Bildmuseet (Umeå), Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, (Turin). The archive includes materials by 16Beaver, Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée (AAA), Mitra Azar, Gianfranco Baruchello, Petra Bauer, Pauline Boudry, Brigitta Kuster and Renate Korenz, Bernadette Corporation, Black Audio Film Collective, Ursula Biemann, Collettivo femminista di cinema, Copenhagen Free University, Critical Art Ensemble, Dodo Brothers, Marcelo Expósito, Harun Farocki and Andrei Ujica, Rene Gabri and Ayreen Anastas, Grupo de Arte Callejero, Etcétera, Alberto Grifi, Ashley Hunt, Kanal B, Khaled Jarrar, John Jordan and Isabelle Fremeaux, Laboratorio di Comunicazione Militante, Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson, Angela Melitopoulos, Mosireen, Carlos Motta, Non Governamental Control Commission, Wael Noureddine, Margit Czencki / Park Fiction, R.E.P. Group, Oliver Ressler and Zanny Begg, Joanne Richardson, Roy Samaha, Eyal Sivan, Hito Steyerl, The Department of Space and Land Reclamation, Mariette Schiltz and Bert Theis, Ultra-red, Nomeda & Gediminas Urbonas, Trampolin House (Morten Goll and Tone O. Nielsen), Dmitry Vilensky and Chto Delat?, James Wentzy.

7. Hardt, M. and Negri, T., Declaration.

8. See Lazzarato, M., Videofilosofia. La percezione del tempo nel postfordismo, (Manifestolibri, 1997).

9. Negri, T., Pipeline, (Torino: Einaudi, 1983).

10. See fragments on Vimeo: www.vimeo.com.

11. Simonetta Fadda, Definizione zero: origini della Videoarte fra politica e comunicazione, (Genova: Costa & Nolan, 1999), 129.

12. Steyerl, H., The Articulation of Protest, www.republicart.net, accessed 15 October 2013 and see also Sheikh, S., Positively Protest Aesthetics Revisited, www.e-flux.com accessed 15 October 2013.

13. Omar Robert Hamilton, Capturing Our Changing Realities, 2011, cinerevolution-now.blogspot.it, accessed 15 October 2013.

Marco Scotini is an independent curator and art critic based in Milan. He is Director of the department of Visual Arts and Director of the MA of Visual Arts and Curatorial Studies at NABA in Milan. He is Editor-in-Chief of the magazine No Order. Art in a Post-Fordist Society (Archive Books, Berlin) and Director of the Gianni Colombo Archive (Milan). He is one of the founding members of Isola Art and Community Center in Milan. His writings can be found in periodicals such as Moscow Art Magazine, Springerin, Domus, Manifesta Journal, Kaleidoscope, Brumaria, Chto Delat? / What is to be done?, and Alfabeta2. Recent exhibitions include the ongoing project Disobedience Archive (Berlin, Mexico DF, Nottingham, Bucharest, Atlanta, Boston, Umea, Copenhagen, Turin 2005–2013), A History of Irritated Material (Raven Row, London 2010) co-curated with Lars Bang Larsen and Gianni Colombo (Castello di Rivoli, Turin, 2009), co-curated with Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. He has curated solo shows and retrospective exhibitions of Santiago Sierra, Deimantas Narkevicius, Jaan Toomik, Ion Grigorescu, Regina Josè Galindo, Gianni Motti, Anibal Lopez, Said Atabekov, Vangelis Vlahos, Maria Papadimitriou, Armando Lulaj, Bert Theis and many others. His most recent exhibition was Disobedience Archive (The Republic) for the Castello di Rivoli (Turin) and he is currently working on an exhibition project dedicated to the art from Eastern Europe, to be opened in January 2014 in Bologna.