Double Crisis

Architecture and the Good Cause

May 12, 2014review,

The Good Cause at Stroom Den Haag addresses the military, political and cultural complexity of rebuilding operations. Can architecture contribute to a sustainable world peace? Roel Griffioen & Stefaan Vervoort critically question the exhibition and its premises.

In recent years, a number of exhibitions have aimed to retrace, reformulate and restore the social dimension of architecture. In some instances, this desire for social urgency manifests itself in dreams of bigness: future bigness in the case of new “smart” cities and sustainable tech-towns, past bigness in the case of nostalgia for historical examples of strong public architecture or urban design, for instance in the post-WWII planning apparatus in the Netherlands, or in the anonymous public works of the 1960s and 1970s applauded in the exhibition by OMA, Architecture by Civil Servants at the last architecture biennale in Venice.1 More commonly, however, “architecture of consequence” (to echo the title of an exhibition at the former Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAi) in Rotterdam)2 is envisioned within the domain of architectural acupuncture: well-placed, site-sensitive and bottom-up interventions. The 2010 to 2011 Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) exhibition Small Scale, Big Change3, for example, showcased a selection of handpicked projects from the four corners of the world that according to the museum’s press release “signal a renewed sense of commitment, shared by many of today’s practitioners, to the social responsibilities of architecture.”

The exhibition The Good Cause: Towards an Architecture of Peace – initiated as a research and publication project by Dutch architecture platform Archis in 2010 and presented at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal before travelling to Stroom Den Haag – clearly taps into this trend. Duplicating both the emphasis on architectural micro-makeability and its projection of big-scale change, the show focuses on eight projects of architectural peacekeeping and social stability that tackle the role of architecture in territories engaged in or following periods of conflict. In turn, these case studies are linked to maps, schemes and diagrams of post-WWII wars, international laws and UN-based pacification methods – which in the case of this iteration of The Good Cause are connected to See You in The Hague, an umbrella program initiated by Stroom Den Haag that aims to shed light on the city of The Hague as a global centre of justice.4 In doing so, the project makes a claim to march towards a twofold goal: “on the one hand it aims to influence governmental political and military decision-making with regard to peace- and reconstruction missions; on the other hand it wants to provide architects and urbanists with extra tools and with insights into their action radius.” This goal resonates with the “forums” and “fields” method as developed by the research project Forensic Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London, which, among other things, extends architecture beyond the built object and nudges it into a network of discussion platforms and interventionist toolboxes.

The Good Cause similarly transposes architecture into a broad cultural domain: projects range from a historical reconstruction of a public garden to a manual for building typologies and regulations; architectural tools vary accordingly. Still, the feeling cannot be done away with that the main thematic of the show somehow neutralizes or at least papers over the interesting elements of these cases. For what is “the good cause”? Should not this category be questioned in each and every project, rather than assumed as the basis for their selection and presentation (as – the accompanying folder to the exhibition describes these as cases of “good practices” – is being done now)?

In an introductory note to the project’s website (www.architectureofpeace.org) the Archis team justly acknowledge that “reconstruction is a highly political process in which every step that is seen to favour one side over another can ignite new violence,” adding that “unbalanced reconstruction can create new inequalities, which would lead to new grievances.” Further, in an Archis publication that precedes this exhibition, Volume’s theme issue Architecture of Peace (2010),5 social scientist Gerd Junne is equally cautious about making big claims toward “architectures of peace”, which he fears are often at risk of capsizing into architectures of conflict: “You build in the wrong place, or with the wrong people, or with the wrong symbols … there is a very great chance you’ll get it wrong.” Indeed, it is the reversal of the exhibition’s title, Architecture of Peace: Towards the Good Cause, which would start to reflect on “the good cause” as an epistemological, sociopolitical and ethical horizon, and concurrently, begin to ponder the precarity of local works that reach towards a quasi-theological and, in fact, idealist goal. Before advancing micro-makeability as a panacea against all possible ills, this approach could chart the possibilities, challenges and limitations of practicing and/or placing architecture in communities plagued by a lack of resources, social sensitivities and other difficulties. Most of all, however, it would acknowledge the tension in connecting local projects to something as vague and universal as the good cause, which contends to inject these projects with architectural meaning and significance.

The exhibition, however, makes no real effort to resolve these tensions, which can be found lingering on three distinct levels: genres and types of architectural objects, rhetorical positioning and the interchange between the two. A first discomfort radiates from the use of architectural representations. Upon entry, two rotational and two steady walls confront the viewer with maps and diagrams that stake out the show’s thematic backbone: an abridged history and world map of postwar conflicts and peacekeeping missions; diagrams of “negative peace” and its concurrent dilemmas; and a historical indexing of international law and tribunals. Suggested by titles such as Wars of the World 1945–2014 or Peace and Justice 1945–2014, however, the scope and abstraction of these mappings, along with their appeal to transparent communication and analytical veracity, is both incredible and problematic. In the Wars of the World map some 140 wars are represented through cartographic symbols and diagrammatic bars based on death toll, duration and classifications such as “Interstate War” or “Civil + War”; on the flipside of the wall is an index of UN-peacekeeping missions that set out to quell such conflicts. Here, of course, the message is that war and peace – as two large-print words on another rotating wall make abundantly clear – are dialectical. But what does such a dialectics reveal about the military, political and cultural complexity of rebuilding operations? The specificities of conflict and reconstruction, ignored in grand maps like these, seem precisely what any intelligent architecture should account for. Whereas diagrams could unpack the conflictive nature of building-as-remaking, in this case they mostly invite random and even laughable comparisons between, say, the conditions of the Suez Crisis (duration: one week; ca. 2000 deaths) and those of the Iraq War (ongoing since 2003; from 100,000 to 600,000 deceased), or the costs of diverse war tribunals (between 18 million and 1,7 billion euros), a year of Wall Street bonuses (15 billion euros) and the Olympic Winter Games in Sochi (36 billion euros). One of the resulting yet dubious suggestions is that peace is measured and understood in processes of quantification, and that architectural diagrams – as transparent tools of measurement and visualisation – simply serve to get us there.

For an exhibition of this type a major challenge lies in establishing an architectural forum that convincingly connects abstract curatorial narratives, which often describe large-scale and long-term developments, with case studies that are usually presented as local solutions to local problems. As the local comes to bear on the global, architecture is recast as a rhetorical technology whose plausibility depends on the link between the concrete and the general, the specific intervention and social or political thematic. In other words, the degree to which an exhibition succeeds in its communication is largely dependent on how its rhetorical structure attempts to credibly overcome the natural discrepancy between very meta and very mini. In the case of The Good Cause, both in terms of the content and its exhibition scenography, it is very difficult to establish a meaningful link between the data-steroidal maps and the selected case studies, which are modestly presented on four tables in the main exhibition room. The cases differ widely in scope and scale, and vary from the redevelopment of the entire center of an ancient village in the Palestinian territories to encourage local culture and boost tourism; to a charming but peculiar school that encourages skateboarding as an instrument of youth empowerment in Kabul, Afghanistan; to a football court cum sanitation center in a dense residential district in Kigali, the capital of Rwanda. Interestingly, the presentation of the projects – and here we return to the rhetorical architecture of the exhibition – betrays a strong curatorial preference to highlight architecture as a “process”. Rather than showcasing the built object in divine isolation, snippets of “process” are fed to the visitor, whether in portrayals of the architect with local stakeholders, in diagrams that show the design arising from the program and the design process, or in photos that document how local workers collaborate on the design or co-construct the building.

The current obsession with process is perhaps an overcompensation, a side effect of the much needed but arduous dismantling of the cult of the Auteur-Architect, with its premises of solipsism, originality, creatio ex nihilio, and so on. The countless architecture publications, reviews and events that still revolve around the Man-and-his-Work-formula – how architect so-and-so tackled design problem such-and-such – prove that any attempt to shift the emphasis toward process deserves to be applauded. We should be imbued by the obvious truth that architecture is not only, as Le Corbusier insisted, a pure creation of the mind, but also the fruit of deliberation, negotiation and trial and error. Yet instead of demonstrating exactly this, the material presented in The Good Cause seldom really tells you anything about the conditions in which these specific – and we assume, noteworthy – examples of “peace architecture” came about. Little information is given on the specificities of the conflict and its aftereffects; the problems and challenges encountered by the team; the funding situation; the relationships between client and community, client and designer, designer and community, etc. Nonetheless these specificities would disclose just how vulnerable and difficult architectural processes in post-conflict situations are, how laborious, demanding, vital but also often unrewarding. At its best moments, the attention to process suspends normative criteria of architectural judgment that tend to obscure the ad-hoc and emphatic character of social projects: a case in point is Skateistan, a school system built upon skateboarding culture and kids having fun, which hardly, if not at all, bothers over questions of aesthetics, “criticality”, or context. At its worst moments, however, one starts wondering whether “process” is not in fact a fig leaf covering up the fact that these questions overall are disregarded in the first place, strategically shrouding the criteria that distinguish architectural production from mere social work. In their place, alternative yet highly dubious criteria are introduced in a recurring tick-box that claims to “weigh” and “measure” the success of all projects: Trust? Check. Employment? Check. Ownership? Check. Modesty? No (too much design, perhaps?). Publicness? Check.

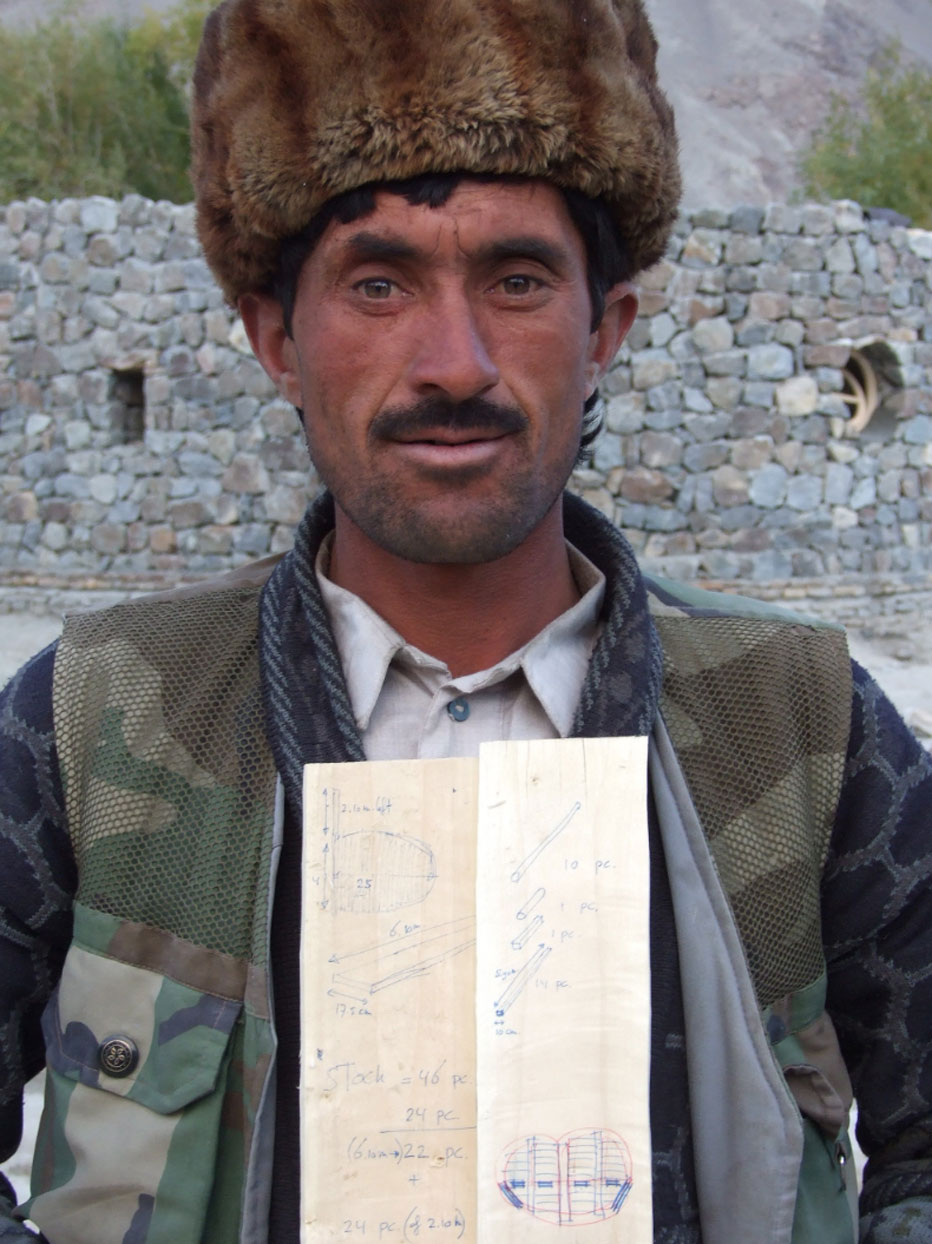

A third and recurring problem – which involves the former two – is the conjecture about the interrelation between the aesthetic and the political. The most telling case in this niche is the visitor’s center designed by AFIR Architects in the Pamir-i-Buzurg Wildlife Reserve, Afghanistan, which is pictured on the cover of the exhibition brochure. Set in the rough landscape of the northeastern Wakhan Corridor, the project lodges the keepers of the reserve, functions as an entrance pavilion and sporadically serves as a community centre for the neighbouring villagers. The exhibition text stresses the use of local fabrication means and methods (“surrounding willow sticks and poplar planks … normally considered not strong enough for construction” are used), and the fact that 104 unskilled local workers have added to the construction (which helped to “develop local expertise and provide employment to create a sense of ownership”, or in tick-box parlance, to invoke Trust, Employment, Ownership, Continuity and Time). The project documentation similarly tells of a “grass-roots architecture” that sets out to “work with community” and to “listen first, then talk.” Also depicted in the documentation is a silver jug from the 1927 Cubic coffee set designed by Erik Magnussen and Isamu Noguchi’s “carefully sculptured rock stone sculptures” – objects and practices that seemingly served as reference points to AFIR Architect Anne Feenstra.

Yet despite these references, the viewer is left to wonder what actually took place, both in the design and the construction process, as an emblematic yet mute building remains entirely undocked from the “expertise” and “ownership” ascribed to it. From whence, for instance, comes its ellipsoid ground plan, the quasi-organic detailing of the windows, and the odd, crystalloid structure of the roof? Do these aesthetic choices relate in any way to an existing legacy of architectural construction in northeastern Afghanistan, or are they (as one would rather think) simply traceable to the expressionist aesthetic and the poetic forms of Magnussen and Noguchi? Is the processual merit of the project in other words an excuse to force-feed a western aesthetic to a local community – one that needs to take “ownership” not only over local materials, but also over forms and formal legacies hitherto unknown? In most cases, especially where buildings are at issue, these questions are neither answered nor posed. The aesthetic particularities and choices of a project are simply left to hang, as the conflation of a western and non-western aesthetic is not expanded or even disclosed, and the status and position of references in the design process is basically ignored. Instead, the viewer confronts an ever-expanding rift between politics and aesthetics, in which the building is dislodged from the curator’s or architect’s ideological positioning up until the point of becoming utterly meaningless.

Architecture, EAHN-journal editor Maarten Delbeke suggests, has historically been surrounded and in fact sustained by realities of crisis. Conversely, Delbeke points to something of a continuous internal crisis in architecture, which aims to legitimize and make contemporaneous the discipline in historiographic models, modes of cultural production or interpretations of professionalism. It is the merit of the Architecture of Peace project – and here we specifically have the aforementioned Volume publication in mind – that it exposes and unpacks the first, “external” crisis, reminding us that architecture is very much rooted in the real world, governed by ethical and political networks and situations. Yet it also surreptitiously testifies to the second, “internal” crisis. The exhibition aims to tackle the “crisis” of contemporary architecture by reorienting key elements in its design and production – its representational means, the role and figure of the architect and the political faculty of the building – and by legitimizing the presented case studies in and through them. Had the project and its various case studies been convincingly related, such cascade of crises– in which one “external” conflict solves another “internal” one – may have been kept erect. Now, in a latent and far more problematic manner, it resembles a palliative strategy to safeguard architecture from obsoleteness in an increasingly politicized cultural arena.

The Good Cause, 9 March 2014 – 1 June 2014, Stroom The Hague, Hogewal 1 – 9, The Netherlands, Entrance: free

1. Public Works, Architecture by Civil Servants, OMA, Venice Biennale 2012.

2. Architecture of Consequence: Dutch Designs on the Future, NAi, 19 February – 16 May 2010.

3. Small Scale, Big Change: New Architecture of Social Engagement, MoMA, New York; 3 October 2010 – 3 January 2011.

5. Volume, no. 26, December 2010.

Roel Griffioen is a writer and researcher. He works at Casco – Office for Art, Design and Theory, is an editor for Kunstlicht, and is currently co-initiating The Front Line, a critical research project examining the role of the creative class in urban politics.

Stefaan Vervoort is a Research Organization Flanders (FWO) PhD candidate at the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Ghent University, with a research project entitled ‘Model as Sculpture’. His research focuses on the exchange between art and architecture in the postwar era, as well as on the material formation of modern and contemporary art museums. He is editor of Luc Deleu - T.O.P. office: Orban Space (with Wouter Davidts and Guy Châtel, Amsterdam: Valiz, 2012) and curator of the exhibition Orban Space: Luc Deleu - T.O.P. office (with Wouter Davidts, Stroom Den Haag, The Hague (2013) and Extra City/VAi, Antwerp (2013)). He writes for the art and architecture magazines Camera Austria, De Witte Raaf, Metropolis M, OASE, and San Rocco.