In Search of Ard Al Amal (The Land of Hope)

January 1, 2014artist contribution,

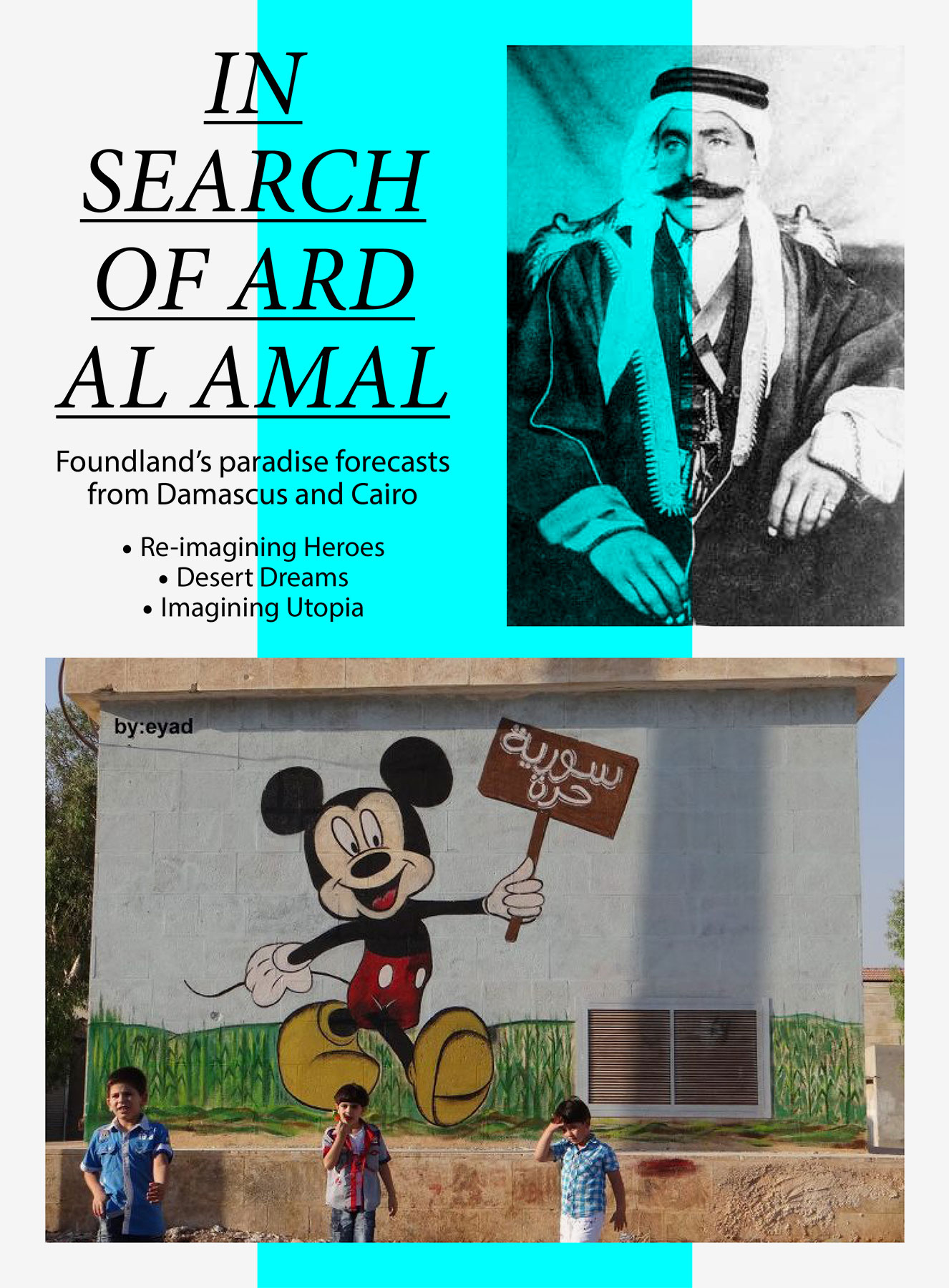

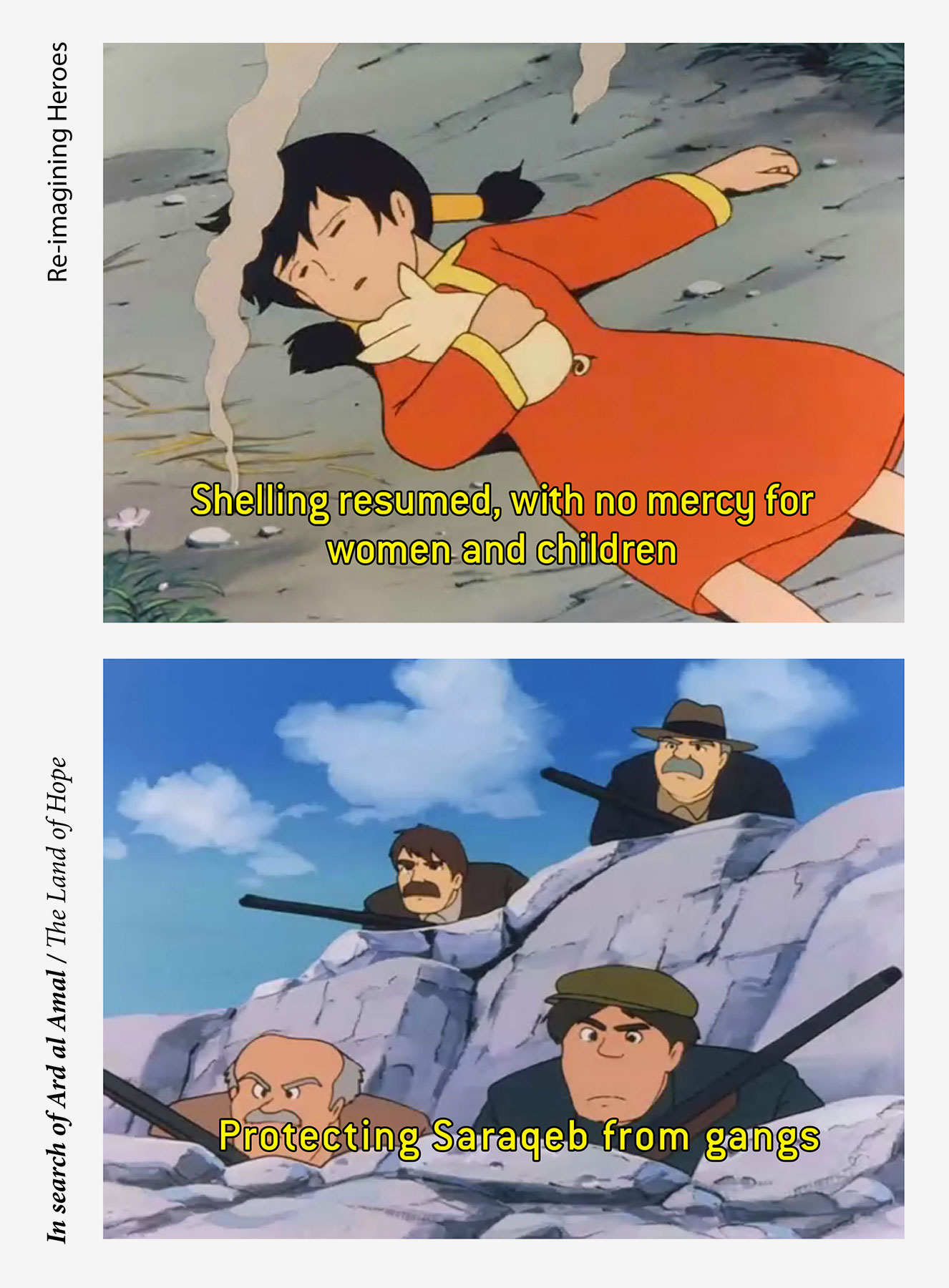

In Syria cartoon characters are appropriated and re-narrated in order to reflect anti-regime protest propaganda.

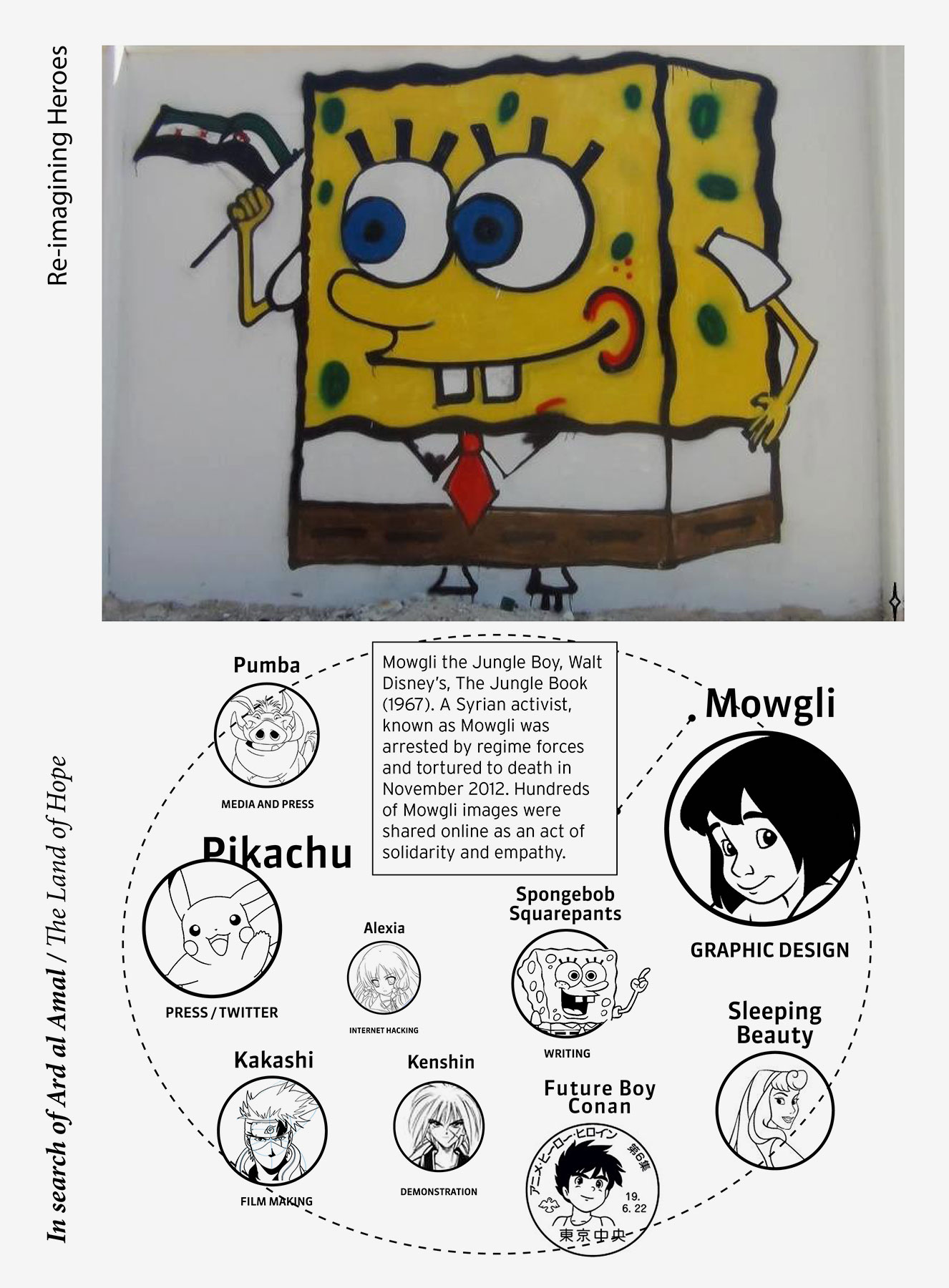

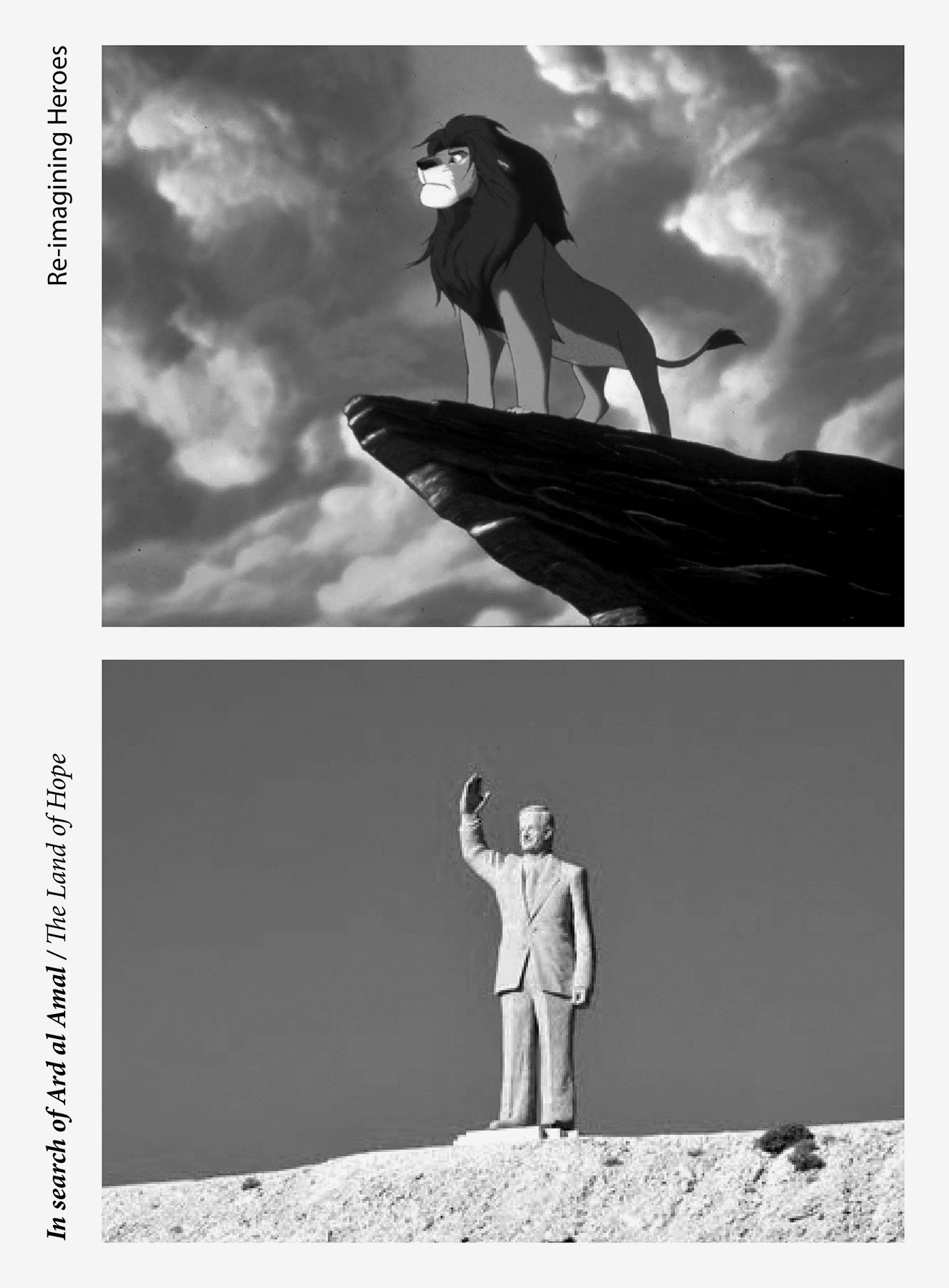

Re-imagining heroes

In 2012, in a small village in the North of Syria called Saraqeb, Mickey Mouse, Woody Woodpecker, and SpongeBob SquarePants all appeared as wall drawings in public spaces. Some of these wall drawings depicted Mickey Mouse holding a sign announcing: “Free Syria”. Photographs of these wall drawings are promoted on Facebook by the group responsible for the artworks. Well-known characters like Bert and Ernie from Sesame Street, Mowgli from Jungle Boy, Simba from the Lion King and SpongeBob SquarePants have all been used within the context of Syrian opposition propaganda. Characters are appropriated and re-narrated in order to reflect anti-regime protest propaganda. Strategies such as re-dubbing and re-scripting are used to ascribe new stories to known characters in order to bring across anti-regime protest messages. Characters are spread on social media where they display their protest messages through the use of familiar narratives, which reminds viewers of characters from their childhood.

A pronounced lack of leadership within the Syrian opposition movement may be the reason why unlikely heroes have served as replacement representations for absent leaders or prominent inspirational real-life figures. Cartoon characters like the ones mentioned above – especially SpongeBob – are very popular in the Arab world, where they are not specifically perceived as originating in the West, since they are all dubbed into Arabic before they are broadcast.

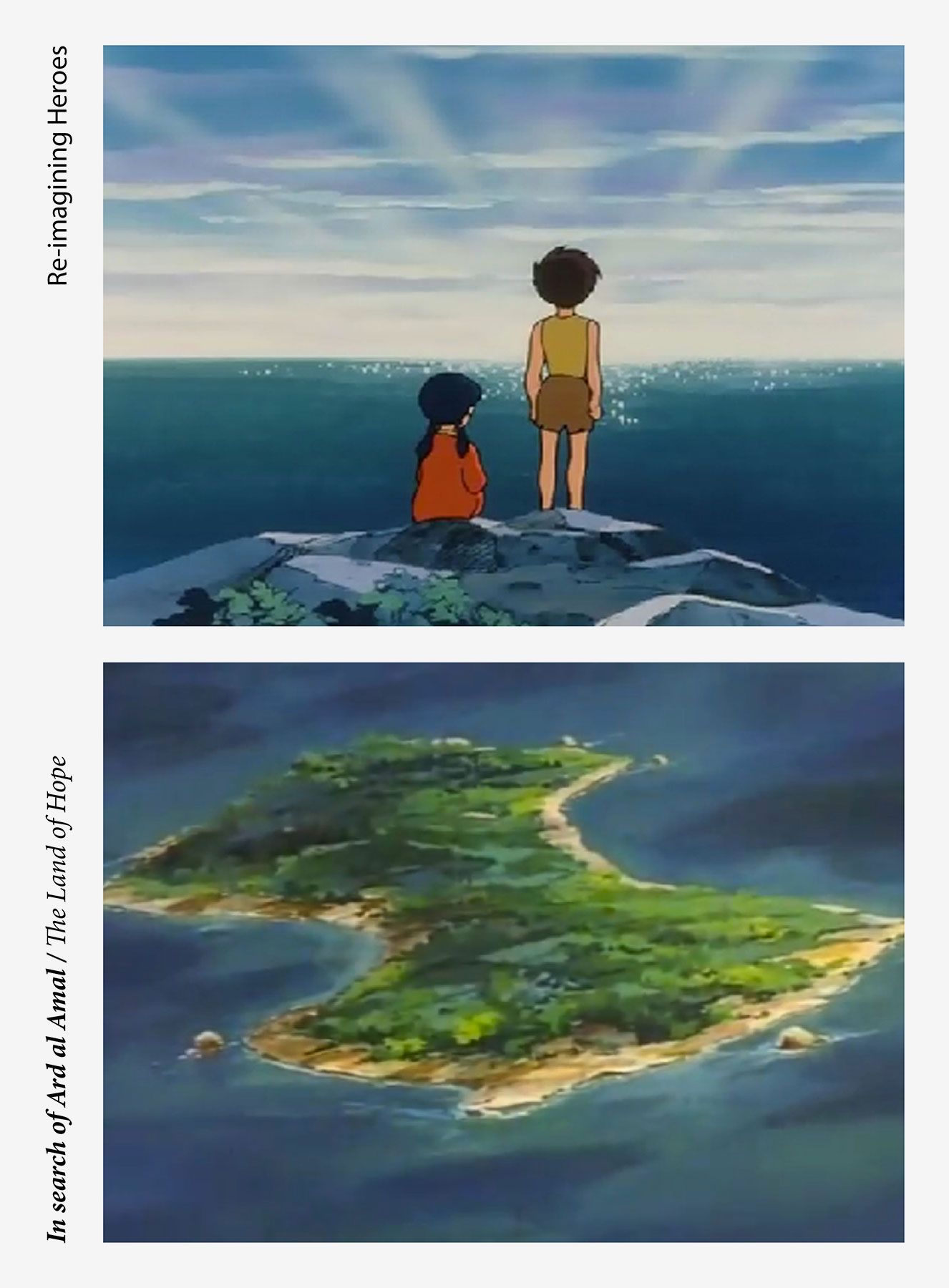

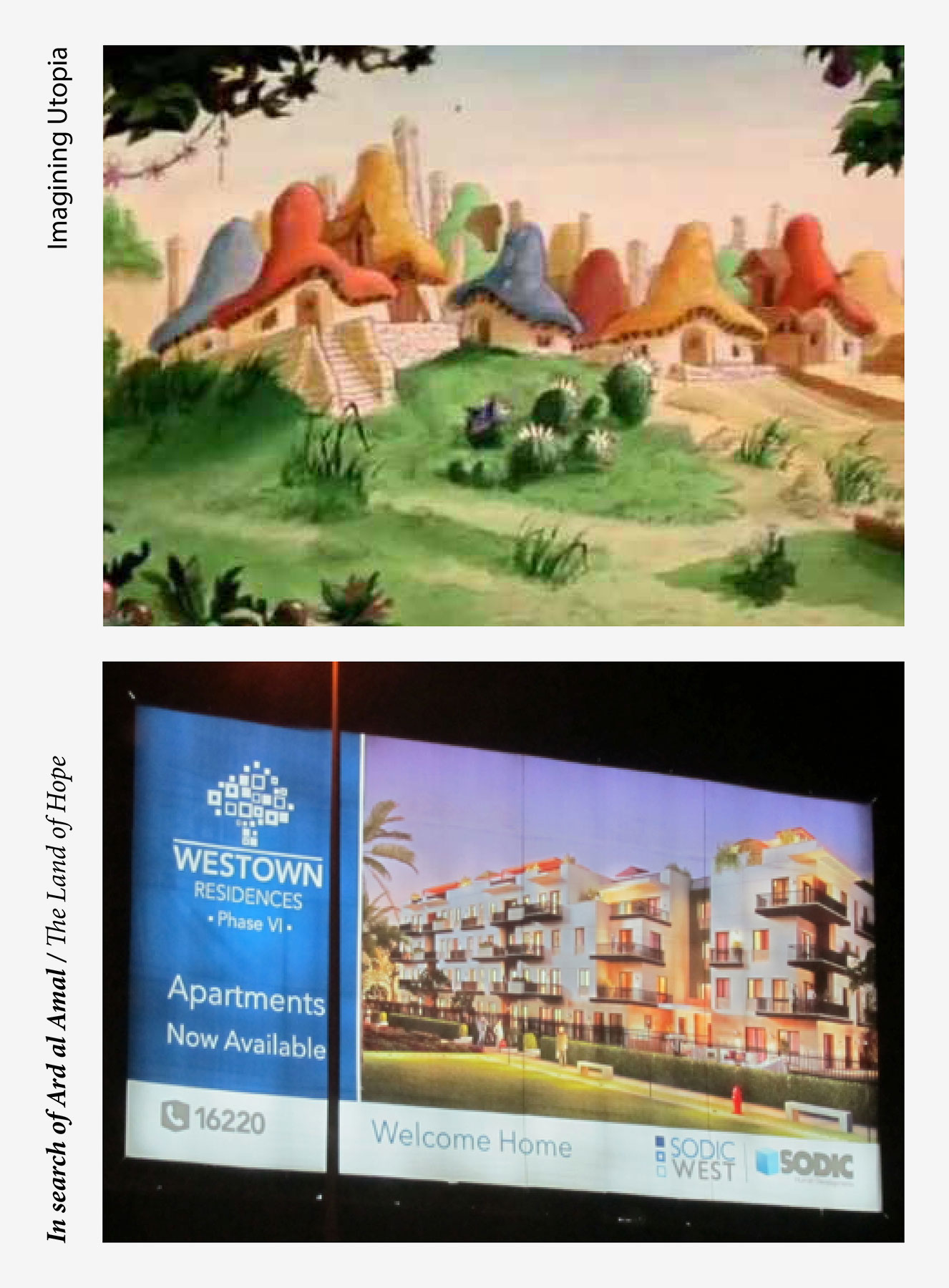

In 2012, we investigated a specific anime cartoon series called Future Boy Conan, or as it is known in the Middle East, Adnan and Leena, which was especially popular in Syria in the late-1980’s. The series was originally adapted from an American futuristic novel, animated in Japanese manga style, and thereafter dubbed into Arabic and disseminated throughout the Arab world. The post-apocalyptic story follows a boy and girl as they encounter great dangers during the course of their journey to find their destination, a paradise called, “Ard al Amal”, a fictional place that the characters never actually reach. Their journeys in seeking this paradise allow them to imagine a community beyond their existing reality, which is characterised by peace and order, unlike the daily nightmare they now find themselves in. Is it possible that cartoon characters and the landscapes they inhabit can provide us with clues that relate to future imagined society models?

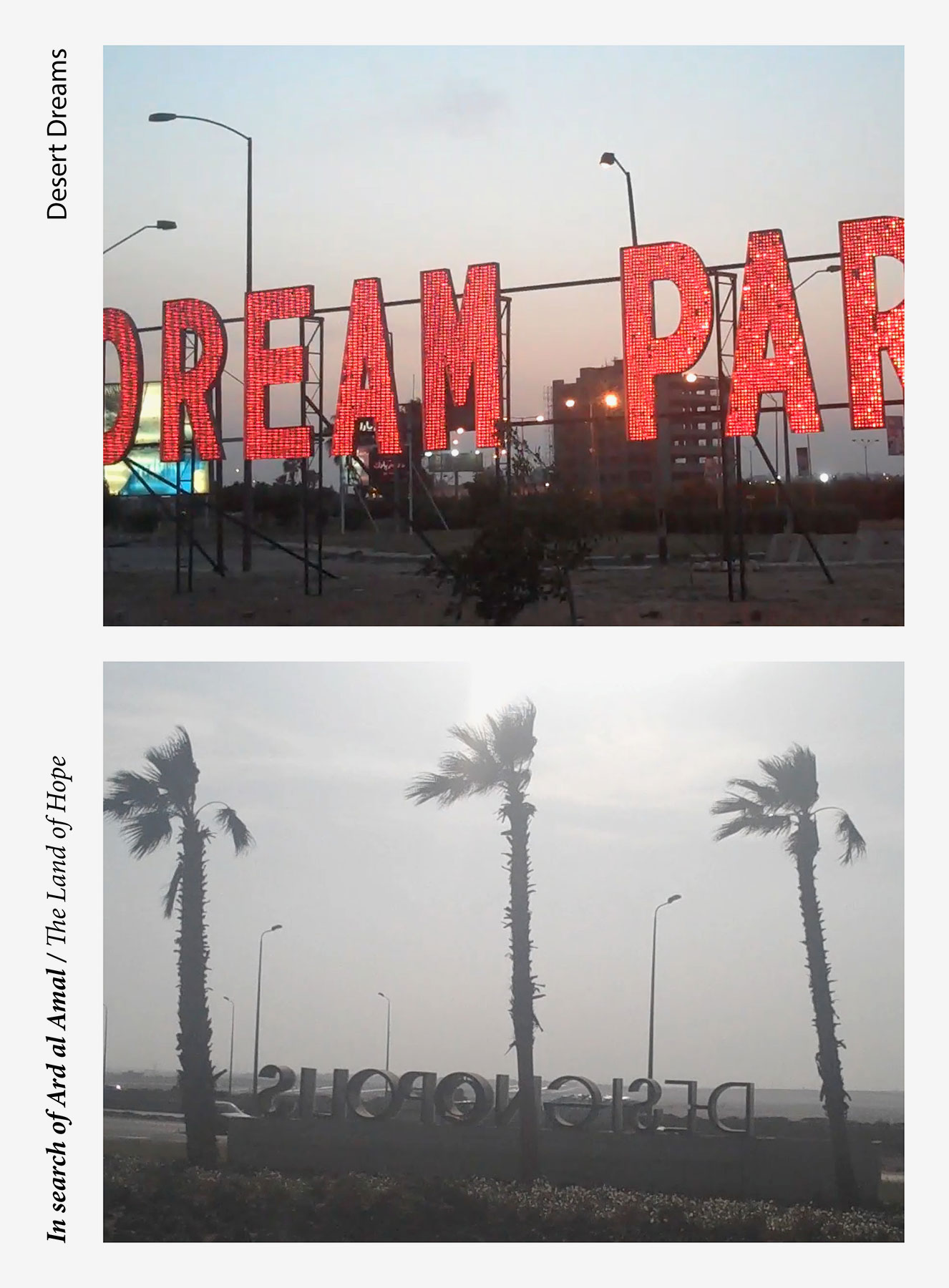

Desert Dreams

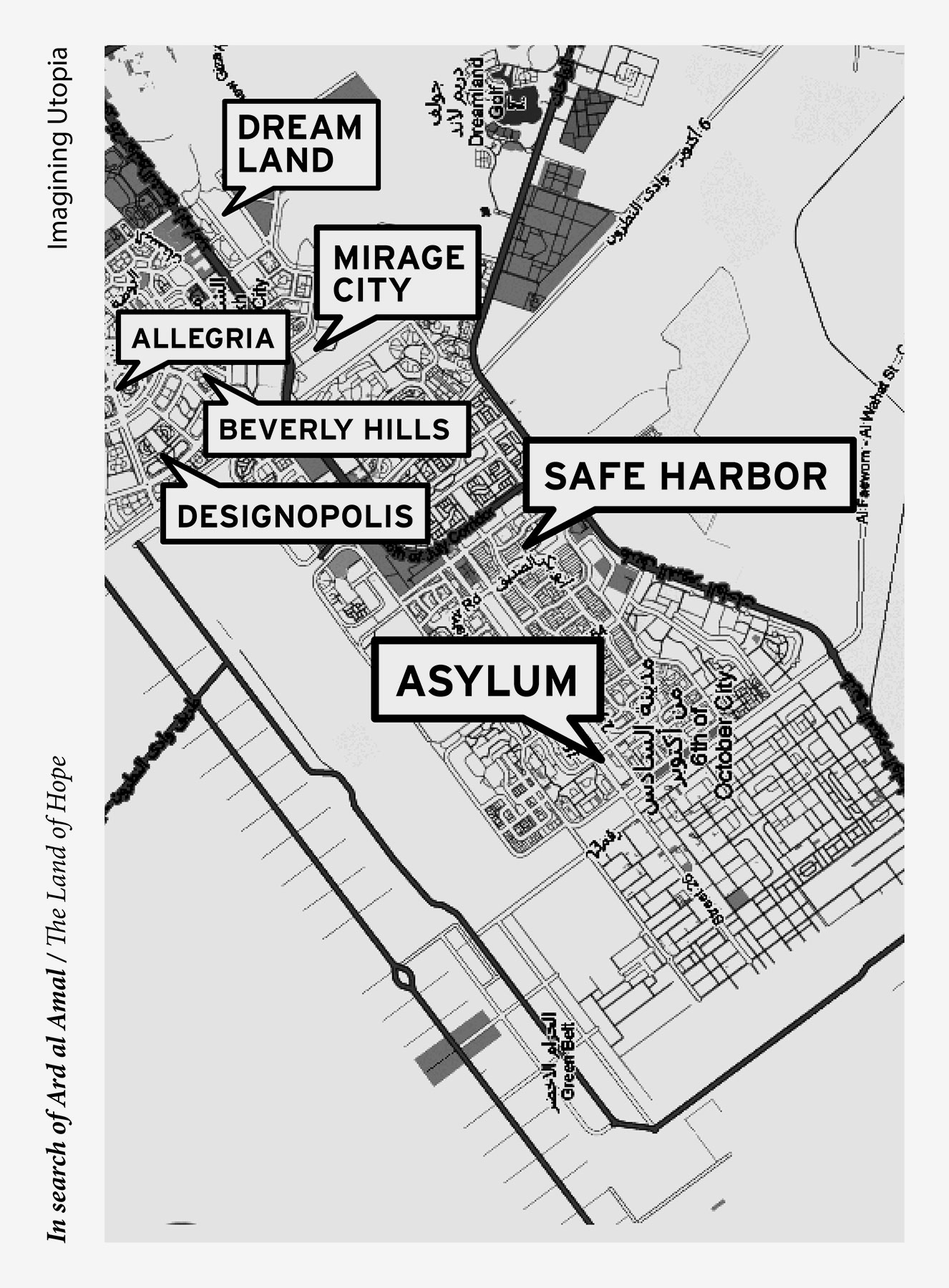

It is the 7th of May 2013, and we are located 40 kilometres outside of the centre of Cairo in one of the city’s so-called desert cities. We are at the headquarters of the SODIC (Six of October Development and Investment Co.), a property development company that is responsible for the mass development of luxury housing in the area. This particular desert city is called 6th of October City, in honour of the day in 1973 that the Egyptians retaliated against the Israelis. It is obviously a date very much associated with Egyptian nationalism. This desert city was originally developed in the early 1980s with plans to eventually house some 4 million people.

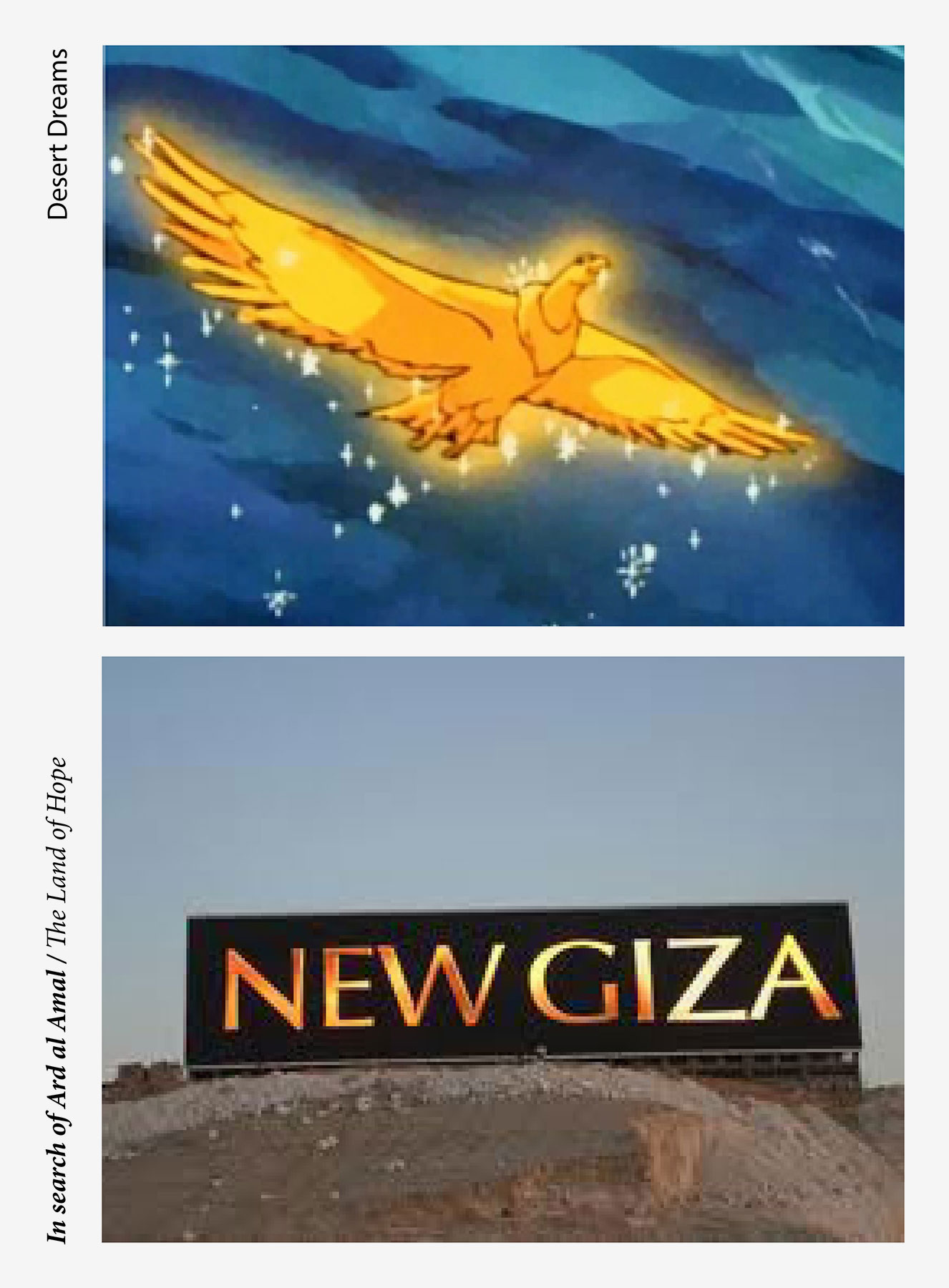

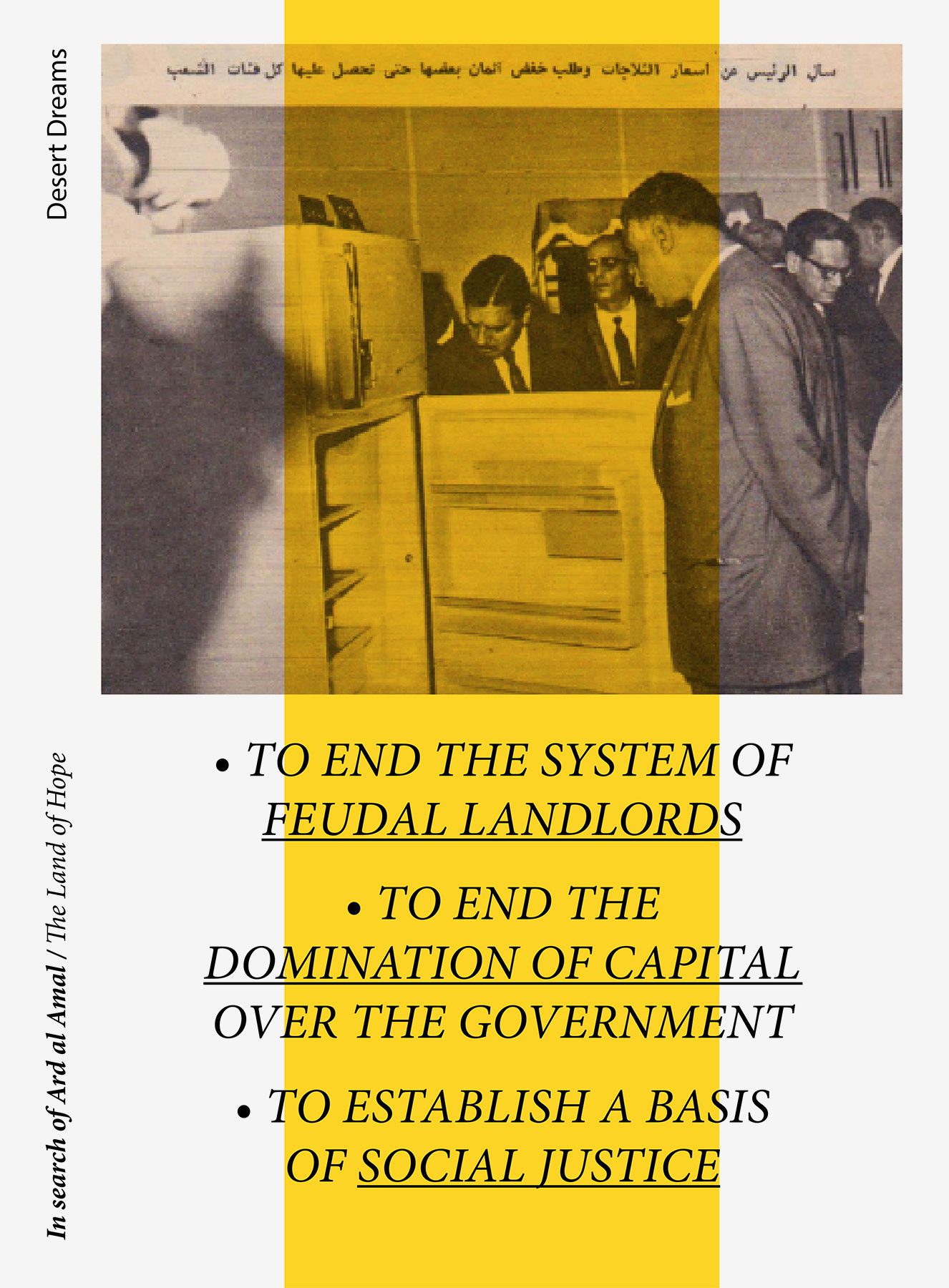

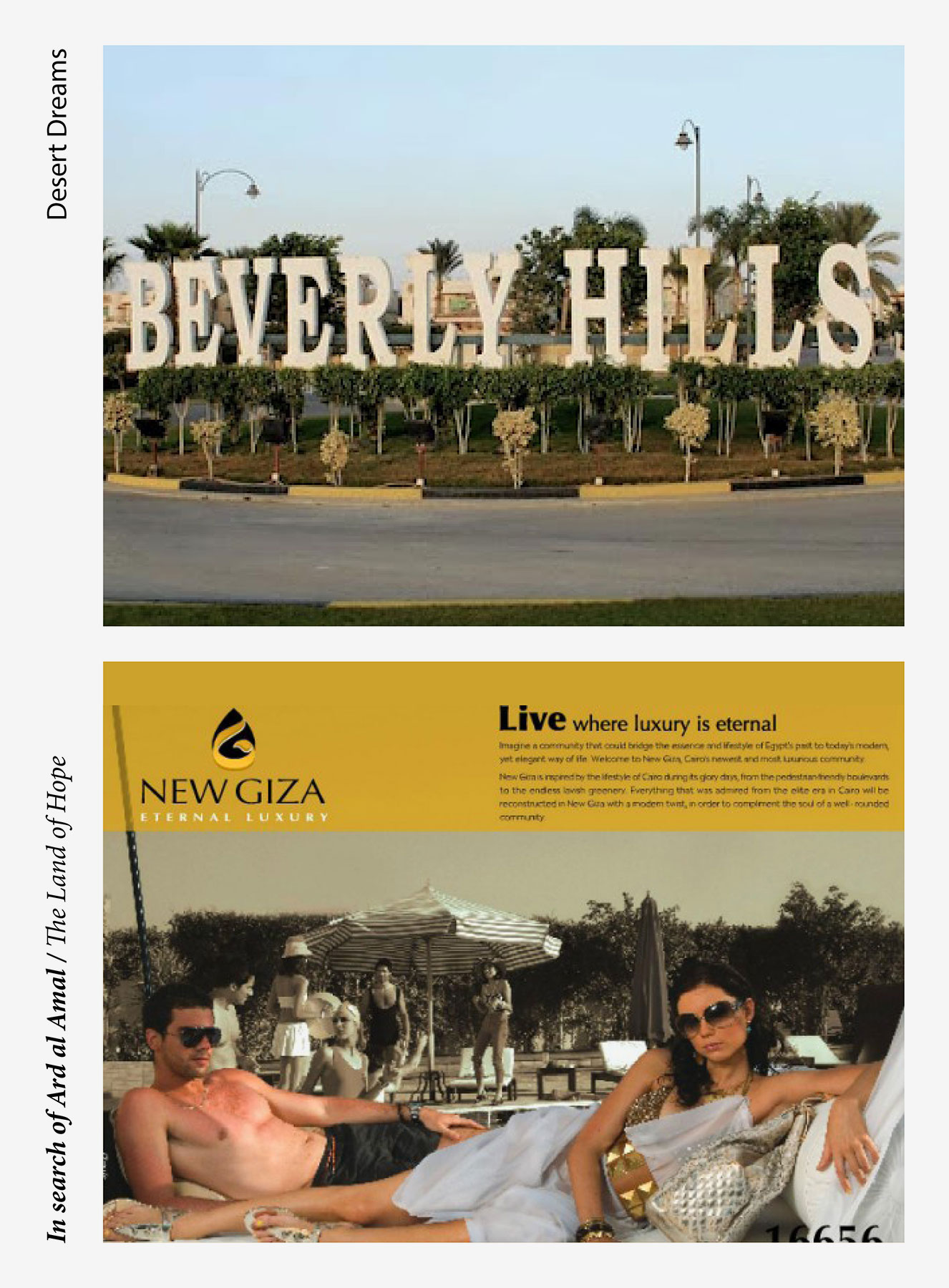

What began in the 1960s as President Nasser’s social-democratic dream to de-centralise overpopulated Cairo by expanding out into the desert has slowly developed into a monolithic gated community for the middle class and the very wealthy. Developments called “Utopia”, “Dreamland”, “Beverly Hills” and “Swan Lake” have come to epitomise the desire of Cairo’s wealthy to escape the dusty and polluted city by moving to the desert, where luxury, air-conditioning and open space awaits them. The land for many of these developments was once Egyptian government or army land that was sold to developers relatively cheaply. Many of these sprawling developments, however, are still relatively empty.

Many of 6th of October City’s residents are newcomers to Egypt including middle-class, Arabic-speaking refugees. Many Iraqi’s began arriving in the early 1990s, after the first Gulf War. A second wave of newcomers consisting of Syrians moved here after violence erupted in Syria in 2011. The new residents create their own communities here, establishing Syrian restaurants, hairdressers and bakeries. Middle-class refugee families are the perfect temporary renters for these under-populated housing developments owned by Cairo’s wealthy speculators. In the desert to the west of Cairo, the home buyers’dream to escape poverty and pollution converge with those of refugees, struggling to carve out a new life in their new homes in this mega-city.

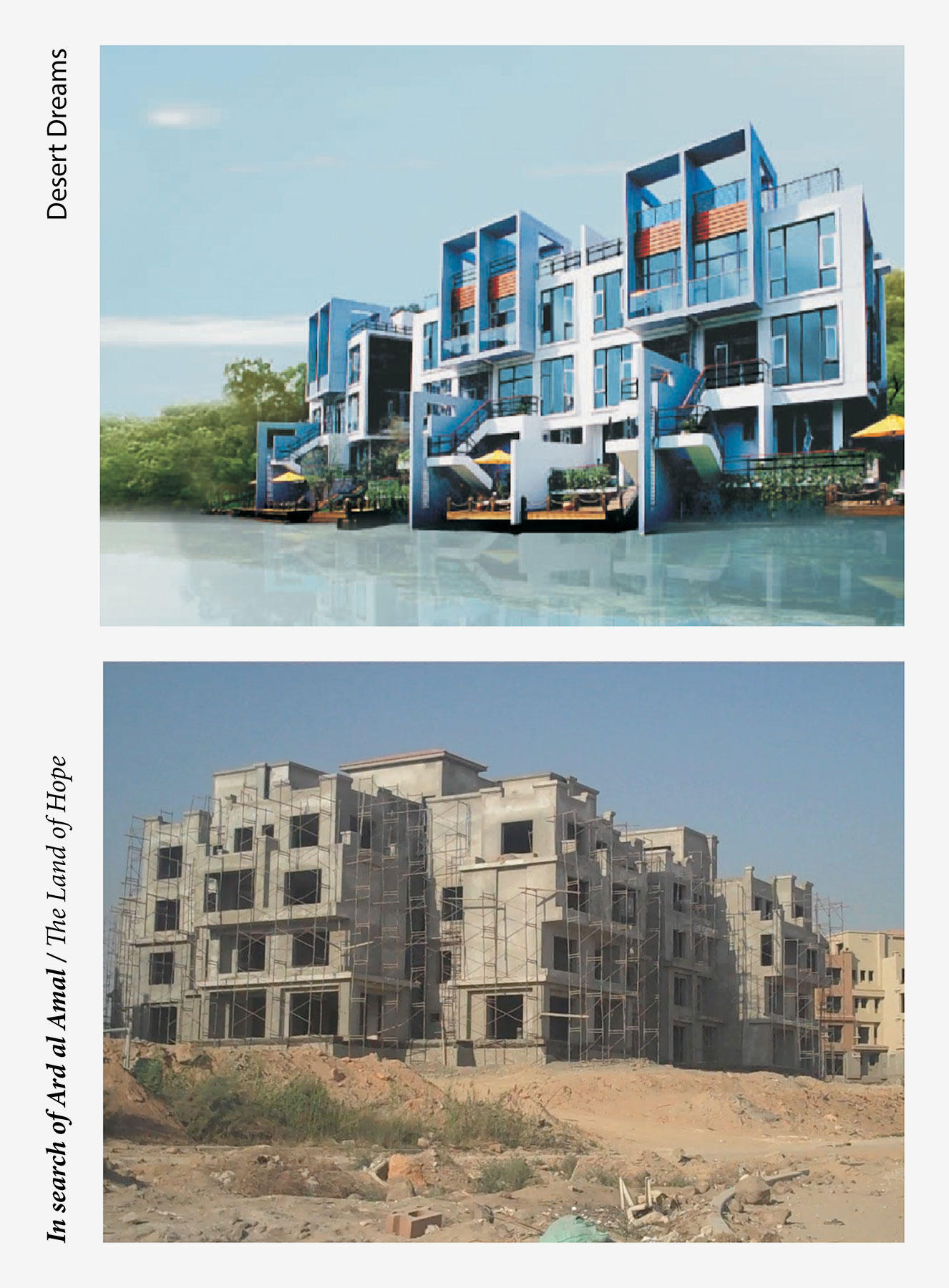

Since we arrived in Cairo in early 2013, we have been intrigued by the images created to promote 6th of October City. The images of idealised lifestyles, and dreamy visions of desert lifestyles commissioned by property developers can be seen on billboard after billboard alongside the highway as drivers head out of Cairo’s wealthier suburbs towards its barren outskirts. Drivers encounter these idealised images every few hundred metres. The aim of these images is to lure potential home buyers away from the political and social upheaval in central Cairo and toward an idealised landscape made real mainly through the use of Photoshop techniques that project beautiful watered and manicured lawns, swimming pools and air-conditioned convenience.

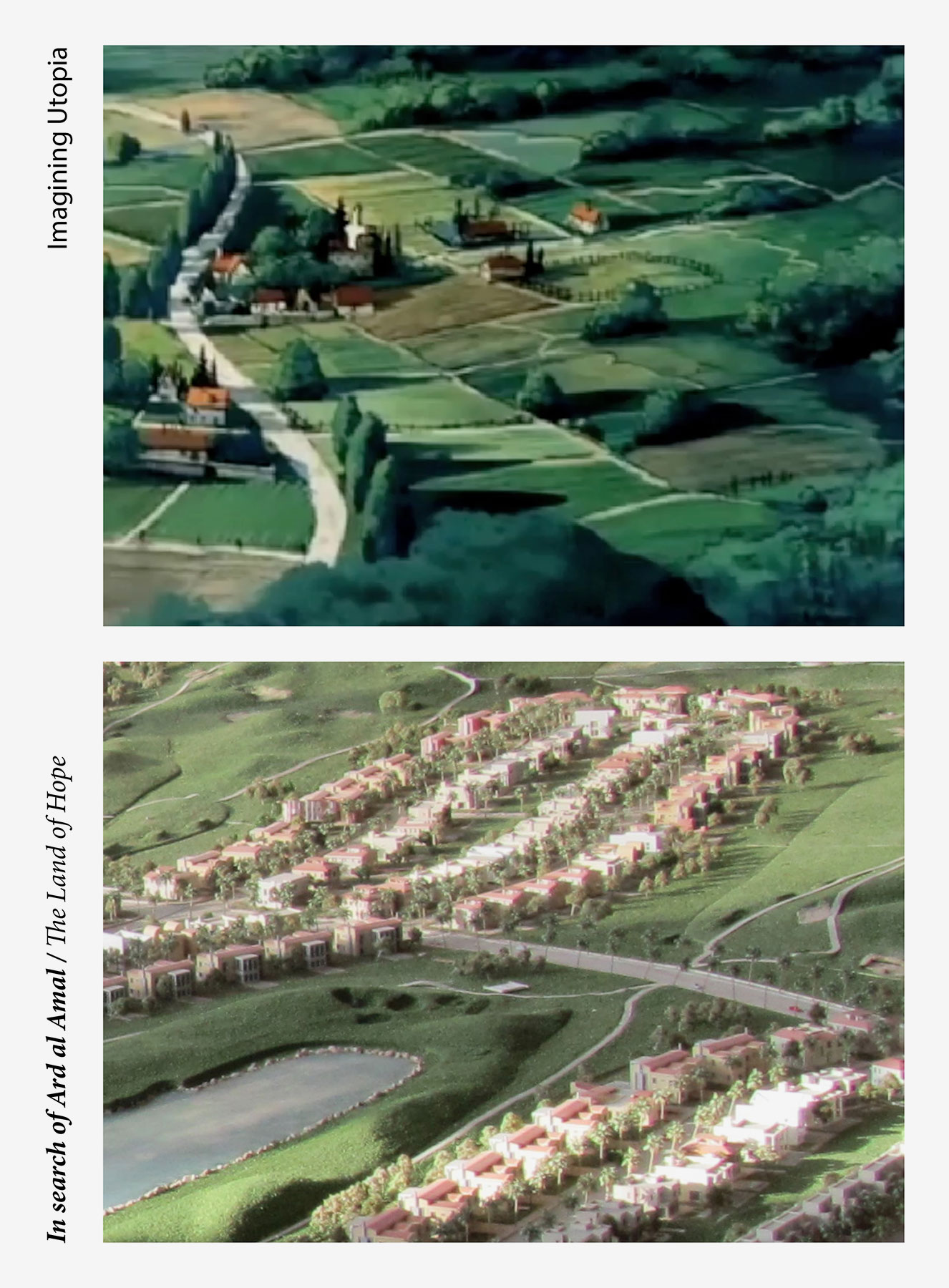

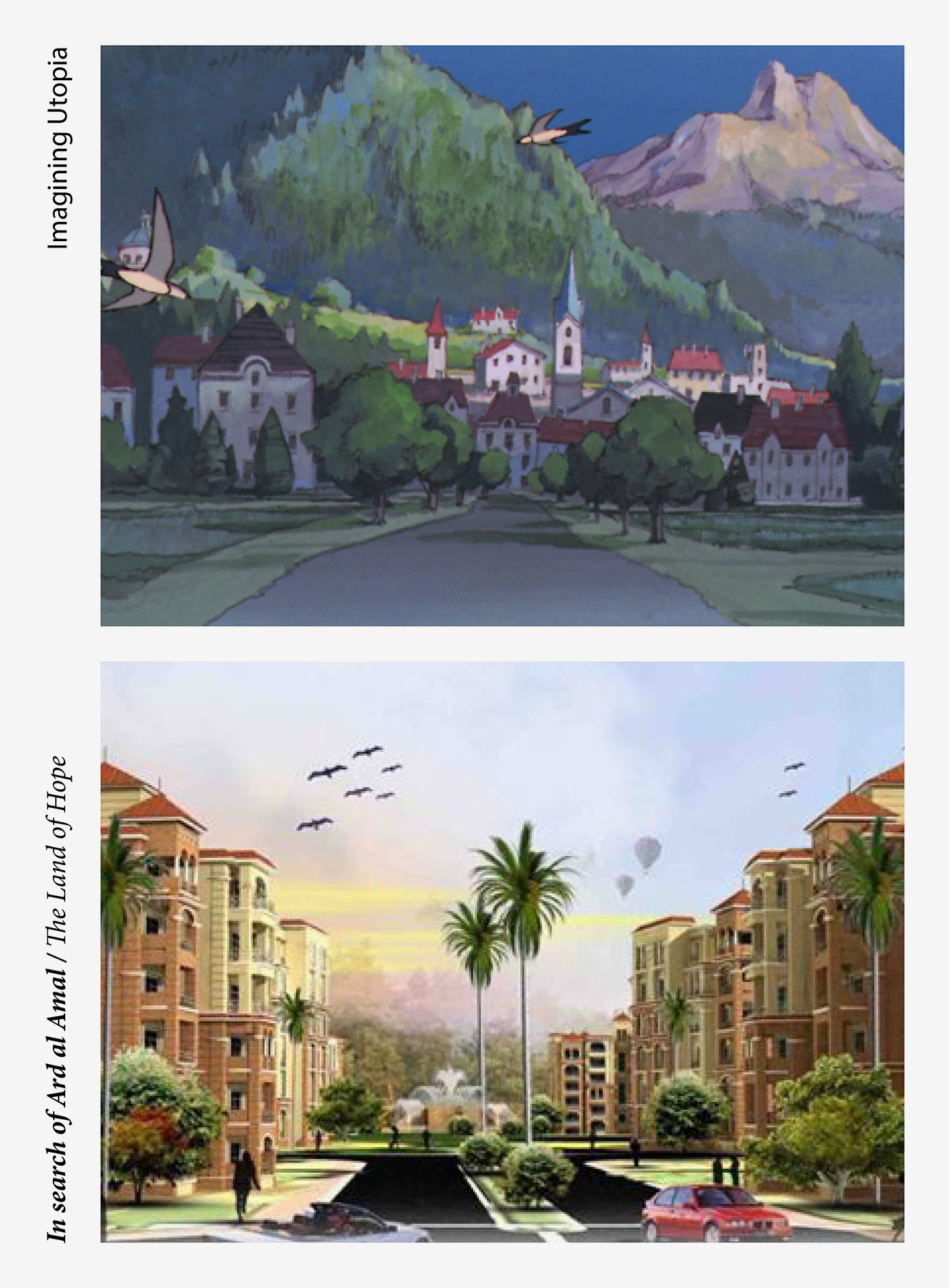

The images of a futuristic luxurious city rising out of the desert sand project the hopes of 6th of October City, while also providing a safe haven for Syrian refugees, far from their war-torn homeland. The depiction of paradise through the use of images taken from Adnan and Leena’s “Ard al Amal” may not be the reality that Syrians discover in 6th of October City, however. But it is interesting to notice how the billboard images of paradise and an unattainable fictional destination from a cartoon series strangely converge in the advertised depictions of paradise. Without necessarily collapsing these two images and assuming that there are any direct similarities of intent or meaning between the two, it is interesting to speculate on their shared vision of utopia, which is mainly characterised by a landscape that depicts no people but plenty of greenery.

While Japanese animators created the image of “Ard al Amal”, advertising agencies hired by Cairo’s wealthy speculators conceived the images used for marketing the new suburbs. The architecture in both cases includes a depiction of paradise that projects a yearning nostalgia for European design and urban planning. They are images of a future life that may never actually exist.

The two sets of images vary greatly in their meanings: the marketing images for the new developments are solely geared towards the selling of homes and imaginary lifestyles. The images of a downtown Cairo in the vicinity of Tahrir Square rife with instability, lawlessness and corruption, target fed-up Egyptians and the idealised images of gated communities depict an escape from this turmoil. SODIC West’s website summarises the attraction: “… provides all the amenities of downtown living without the hassle and the stress.”

The “Ard al Amal” images, on the other hand, may represent an unattainable destination from a cartoon dream, but they also depict the struggles that Leena and Adnan must endure on their journey to paradise. However unattainable their paradise may be it can only ever be reached through struggle and navigation and can never simply be purchased.

Image essay

Foundland Collective (Ghalia Elsrakbi, SYR and Lauren Alexander, ZAR) is a design, research and art practice, based between Cairo, Egypt and Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Since its inception in 2009, the collective have focused on critical analysis of topics related to political and place branding, manifesting their speculations and ideas through visual and written manifestations, exhibitions and publications. See further: www.foundland.info.