Jams, Loops and Downward Spirals in the Academic System

May 25, 2015essay,

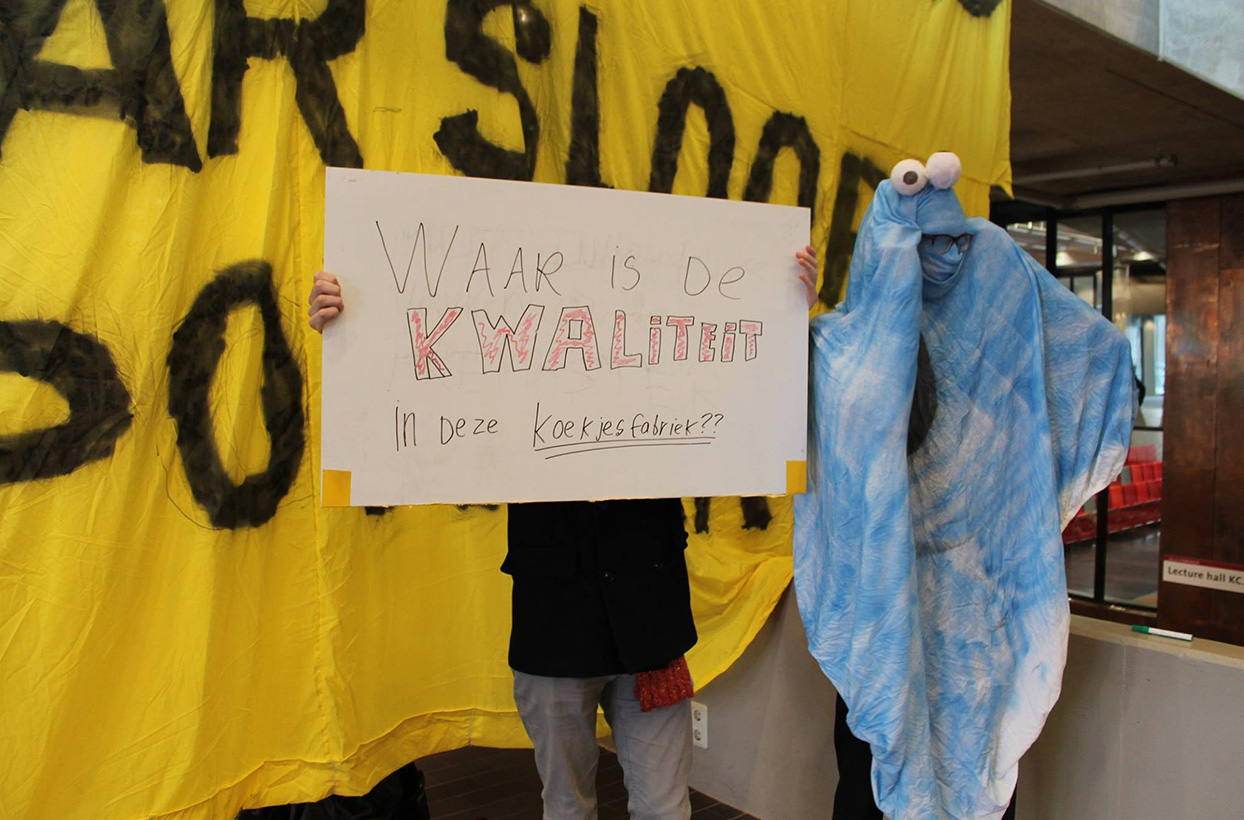

The current protests by students and staff at the University of Amsterdam and other universities in the Netherlands are a sign of very deep structural problems in the academic system. Rather than just a local problem concerning the language departments or the position of the humanities (well beyond the University of Amsterdam or universities in the Netherlands), these demonstrations are a reaction to an accumulation of national and international developments in the way the university is structured, organised and funded.

New public management seeks to quantify and optimise results. But in doing so, it instead creates at least two types of undesired dynamics: a glass ceiling that separates teaching from research, and staggering amounts of uncredited bureaucratic work that is slowly but surely replacing the “core business” of academic labour all together. The situation has adopted increasingly Kafkaesque proportions over the last two decades. The academic ship is about to hit the shore and we need to tack it now in order to remain afloat and ensure that it will continue to be seaworthy in the future. Besides a wide variety of specific problems that need to be resolved locally, it might be useful to illustrate the effects of the accumulation of measures that the average scholar faces in his or her daily routine.

Academics – ranging from assistant professors to full professors – are assigned two main tasks: education and research. These days, however, there is less and less time for actual research and teaching. How did this happen? When it comes to research time, scientists now spend up to 30% of their time just searching for funding for prospective research, as Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant recently discovered in a survey of 500 academics. This reveals that a lot of time is spent formulating and organising research projects within the requirements of pre-established frameworks of national and international competitions. This in and of itself is a rat race that is already worthy of discussion with only less than 20% of all applicants making it through each round of the evaluation process, while the other 80% can keep trying with no guarantee of any improvement in their chances the next time. What remains to be taken into account, however, is that all these proposals also need to be assessed by the academic community itself; mostly through large, heterogeneous, time-consuming committees where not all of the members have the necessary knowledge to accurately assess the full range of topics and fields. Each proposal then, includes at least two or three external referees; these too are the academics themselves who anonymously give their verdict on submitted proposals in blind peer-review processes. The whole cycle of reviewing, references and assessment is, in turn, then checked again. The academics themselves – in other committees, of course – do most of this work. Because this system of research funding via competitive project applications is an international and transnational phenomenon, requests for references, reviews and commissions arrive daily from many corners of the world. Moreover, publishers also require referees for proposals, articles and manuscripts. It is impossible to meet all of these requests, but it is important work. Academics readily offer their help and advice in these activities, as well as other services that include, among others, mock interviews, pitch preparation and the sharing of experiences to help colleagues improve their chances in the competitions. Thus, to the time it takes to write proposals, one must also add at least another 10% to 20% to keep the system running and controlling quality standards. Awarded projects, in other words, require a lot of management and administration. The percentage of research time involved in a university appointment varies, but it never exceeds 50% of a full appointment (not including PhD supervision). A complex calculation is not necessary to understand how precious little time is left to do the actual research or writing. Meanwhile, many universities have appointed additional support staff to draft budgets and provide administrative assistance; but these staffs are also barely able to handle the deluge of applications. An average budget requires two man-hours. An average grant takes twenty days to write.

The chances that a project will be approved are small, but once it is selected, the chances that the next project will also be accepted increases exponentially. Funded research time allows an academic to “buy oneself out” of teaching, in order to have enough time to draft a subsequent application. And it is at this point that a watershed between research and teaching staffs emerges. Staff members with a grant and a permanent job (which is, in itself, becoming increasingly rare) have to be replaced in their teaching duties, usually, by young postdocs or academics who are still working on their PhDs. These replacements are hired on temporary teaching contracts without research-allocated time, and they are, therefore, ushered into an entirely different spiral. The standard number of paid hours per seminar for many teaching tasks or other educational formats has decreased steadily over time and so, these academics have to teach more and more classes to maintain a living wage. At many universities, teaching contracts above 0,7 FTE are deemed excessive and unworkable, and are therefore not offered, simply because an increased teaching workload would never fit into a 24 / 7 workweek. Wages are low and so many young aspiring academics continue to accept these less-desirable contracts even though they are overextending themselves. A young academic in this situation is supposed to feel lucky with this opportunity to remain in the academic world, but sees little opportunity for developing thoughts or observations that might lead to the writing of an article or a research proposal. Their ability to obtain funding or to be shortlisted for a competitive research program is thwarted due to their lack of publications. This system also fails to acknowledge their teaching evaluations or overall academic qualities, which further reduces their advancement potential within academia. PhDs and postdocs entering the system as interims end up entangled in an endless loop of teaching because a temporary teaching assignment only ever leads to another temporary teaching assignment.

Moreover, there is also less and less time for actual teaching. In addition to cutbacks in paid teaching hours – which has already made teaching dangerously overwhelming – the past two decades has seen an explosive increase in bureaucracy, administration and control mechanisms such as: tests, course manuals, key and examination files, second and third readers, and a broad range of standardised forms that all have to be filled out manually, all of which requires enormous amounts of time and energy. A long, intense day of teaching is followed by an evening of correcting tests, papers and assignments, and administrative chores; first for your own students, then for those of your colleagues. Let’s add it up: if you, as a teacher, have to perform a second assessment for a group of 30 students for a colleague, on a final assignment (I’m not even talking about a Master thesis), and you spend 15 minutes per assignment (which is obviously not enough to properly provide a profound assessment or any useful feedback, but just enough to adequately check the control points), it is clear that merely completing this additional form can take the equivalent of a full working day. By working weekends and evenings, a teacher may have one day per week (or, more likely, a half a day and an evening) to prepare one’s lectures and classes.

What is most distressing, however, is that this system sustains a feeling of permanent anxiety and distrust among the teachers. Meanwhile, the students, on their side, are also overwhelmed by tests and rules and regulations that get in the way of real learning and independent thinking. Furthermore, in spite of all the feedback forms, record-keeping and standardised contact hours, students still feel that they are largely being ignored by their overworked teachers, both as individuals and as students who simply want to learn and fully comprehend their course studies. These are the contradictions that the current system of constant checks and balances within the university has created. The ultimate goal of this system is, invariably, to prepare for the external audit committees who, every few years or so, reevaluate every degree program and department based on a constantly changing set of rules and standards. Any potential “risk” has to be addressed by some new measure or regulation. Students, meanwhile, have less and less time and space within which to reflect on the entire process. Learning now means attaining instant excellence with little or no room to make mistakes, change perspective, or acquire a sense of development along the way. And, unfortunately, for the students who are already excellent – and there are many – this system fails to offer sufficient challenges or opportunities for personal engagement. In other words, students and teachers feel increasingly like stressed, hunted prey.

Add to this the fact that the ever-shrinking group of tenured staff members are often too busy securing research grants, assuming their management duties and increased administrative tasks as they coordinate personnel and programs, including the negotiation of ever-shrinking budgets for teachers’ wages or they are constantly teaching. Moreover, the imposition of top-down re-organisations in areas such as semester formats or the restructuring of programs, require endless meetings and constant “creative” input. Many teams manage to join forces and muddle through such reorganisations, but these arrangements only last until next year’s reorganisation year. Similarly, the annual game of “musical chairs” involving replacements, new contracts, applications, dismissals and dealing with disappointments, present yet another level of arduous and negative procedural energy.

With regard to research, besides the laborious aforementioned review processes, the current publish-or-perish model means that there is never enough time for those academics who read much less than they publish. The lauded open-access publishing model, which is based on the extremely legitimate notion of publicly accessible research publications, has developed into a system that requires that authors (i.e., the researcher,, writer,, editor and peer reviewers) also ensure that their grants include the so-called Article Processing Costs (APCs), or else they must foot the bill (APC costs can vary between €500 to €5000). This system may have negative repercussions with a failure to arrange open access meaning fewer readers and fewer citations, which, in turn, means less impact (by citation figures or other measures), which means a lower competitive ranking and a decline in one’s chances to attain future grants, and so on.

All this, however, does not mean that we should return to a system with no sense of accountability or that demands uncontrolled costs and no sense of how to effectively and fairly manage a budget. Sensible corrections have been applied over the years to a system that was untenably expensive and often unproductive. There are great advantages in searching for funding via thematically-oriented projects and collaborations on both the national and international level. Recalibrations, adjustments, the (interdisciplinary) exchange of ideas among colleagues, and the learning of best practices in education, teaching and pedagogy are all healthy developments. But profit-driven management and efficiency measures have created an inhuman and unsustainable system that has reached dangerous levels to the point that research increasingly can only be performed within certain frameworks such as a specific national discourse or top-down programming increasingly determined by the interests of industry and the business community. It is important, however, to improve working conditions and labour contracts. Meanwhile, portions of research budgets must be made available for independent research, smaller-scale projects and special dissertations, so that university research departments can regain some measure of autonomy again.

It is in such a highly diverse research environment that unexpected connections, unpredictable discoveries and potentially invaluable observations and insights can emerge. In the field of education, we need to put the focus back on content that is driven by students and teacher curiosity and enthusiasm. We need to abandon the illusion of quality control through constant testing and monitoring. A positive situation means a diversity of competency where adequate, good and excellent students can all work together. We need to turn the page across the board on a system of distrust and on the prevalent fear of isolated examples of underachievement and poor performance, which currently imposes too many rules and regulations. A return to a system based on trust and common sense would go a long way toward correcting our past mistakes as we move into the future. This would finally allow us to once again turn to the absolutely essential tasks of excellent teaching and research.

This article appeared in Dutch in De Groene Amsterdammer on March 11, 2015.

Patricia Pisters is professor of film at the Department of Media Studies of the University of Amsterdam and director of the Amsterdam School of Cultural Analysis (ASCA). She is one of the founding editors of the Open Access journal Necsus: European Journal of Media Studies. She has published on political cinema, transnational media, neurocinematics and film-philosophy. She is currently finishing a book on the Dutch filmmaker Louis van Gasteren and starting a project on ‘mines and minds’ around the idea of filmmakers and artists as metallurgists.