Memory Archive

December 10, 2021essay,

Taking part in the KABK Research Group gave me an opportunity to reflect on my role in Foundland Collective and specifically on projects that centre around image collections and archives. Through Foundland Collective, the Syrian designer Ghalia Elsrakbi and I work with political images and narratives in relation to issues of migration and conflict, in projects that often emerge from shared experiences during residency periods and personal encounters with places. The collections and archives we work with can be personal, subjective or alternative. Sometimes the archive is the starting point for our research, sometimes it provides the method and, occasionally it provides the format for an outcome.

Simba, the Last Prince of Ba’ath Country

For Simba, the Last Prince of Ba’ath Country (2011), we sourced political imagery related to the Syrian conflict from social media platforms. Specifically we looked on Facebook for pro-Assad propaganda made by pro-regime fans. Then we used the format of a publication to analyse, deconstruct and contextualise the visual iconography and the construction of myth within the images as a way to understand the Syrian conflict as it was unfolding and to capture a specific moment in time. Much of the found digital material is no longer available on the internet, highlighting the importance of our compilation and contextualisation of events as they were taking place.

The global proliferation of fake news and an increased distrust of media reporting demonstrates a need for frameworks that allow journalists more time and funding for factual reporting. This is especially true for journalists in challenging regions, such as Syria, where priority should be given to critical and nuanced narration. The role of storytelling related to news events will have significant consequences for prosecution cases and truth-seeking efforts. Artists, too, have a role to play in following media events and providing perspectives on media-related material. Foundland Collective’s projects have come to find context within spaces of artistic practice and film distribution; however, I believe that the artist as an embedded archivist and creator of narratives still has much to offer the social sciences and journalism.

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s work is a continual source of inspiration. It exemplifies how subjective and creative readings or interpretations of image collections can function within fields of knowledge production beyond art and photography. Azoulay’s image-based reading of Israeli archival photographs taken during the 1940s are subjective reinterpretations that expose the otherwise invisible position of both the perpetrator and the victim.1

By articulating and reflecting on the methods that Foundland Collective has experimented with in the project Groundplan Drawings, and using Azoulay’s approach as a point of departure, I hope to illuminate the role of subjective archive-making in producing new insights about conflict.

Groundplan Drawings (2014–2019)

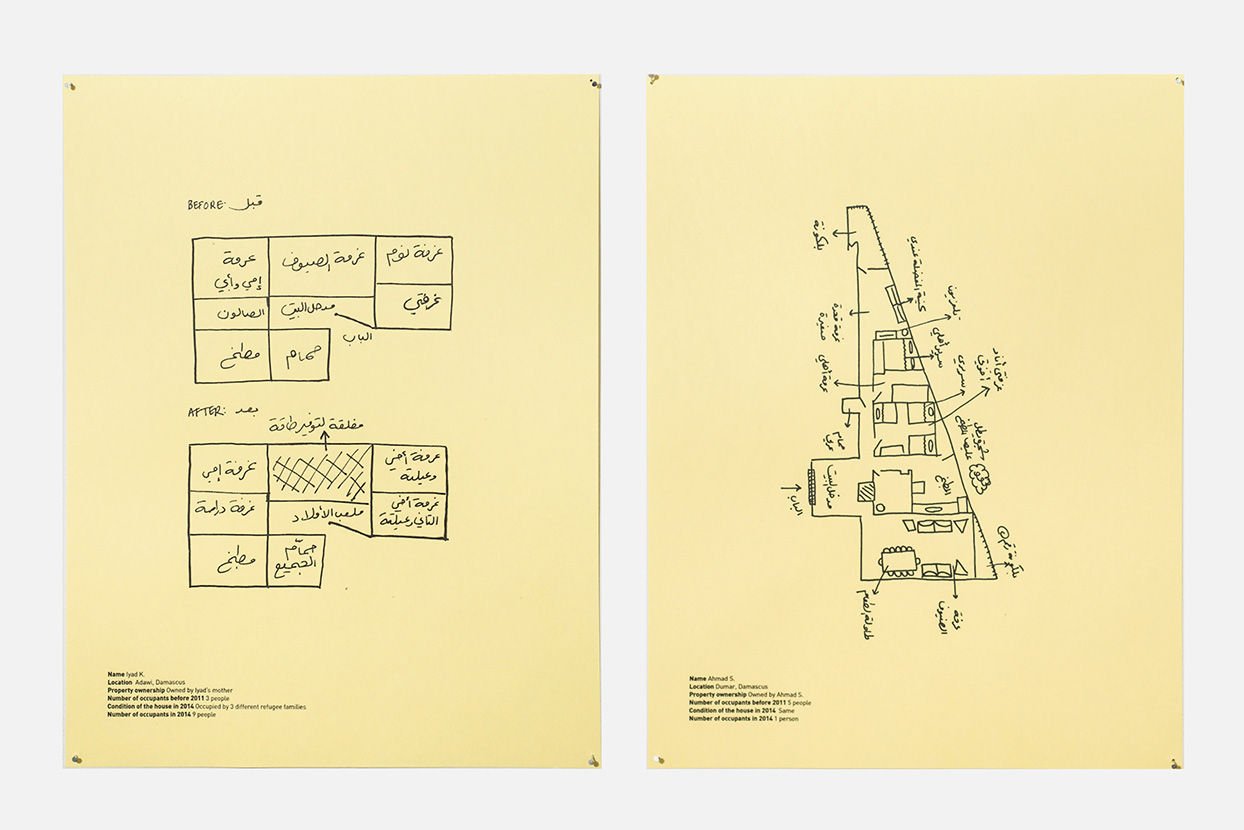

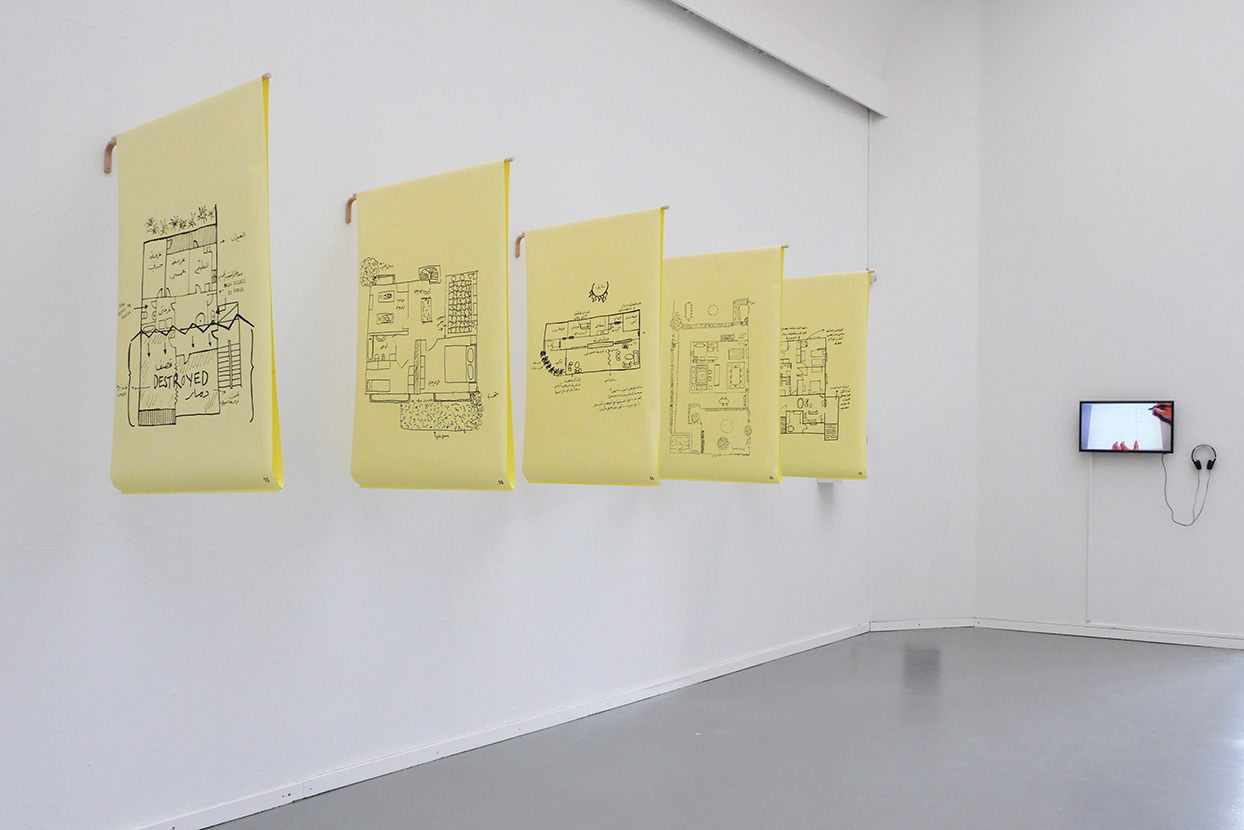

In 2014, while on an artist’s residency in New York City, Ghalia and I spent time with Syrian diaspora friends. This is where Groundplan Drawings (2014–2019) evolved. We asked participants to each make a drawing from memory of their Syrian childhood home. Many of the participants had fled Syria after the conflict erupted and had not yet returned. Most of the participants were enthusiastic as the act of drawing often triggered joyous, nostalgic memories. Some people chose not to participate, as remembering their home and the connected incidents brought up trauma.

Participants approached the drawing of their home differently; some began with little hesitation, while others embraced it as a serious and meditative undertaking that took several days to complete. We also invited participants to talk about and interpret the drawings they had made. The experience evoked memories of the home environment in unexpected, non-linear and spatially triggered ways.

Drawing as a research method is a well-established practice amongst educational psychologists and therapists. According to the handbook Picturing Research, Drawing as Visual Methodology, edited by a group of South African researchers, drawing as a research method should be conducted as a collaborative activity between the drawer and the specialist or interviewer. Participants ‘draw or write about the meaning embedded in their drawings, allowing the drawer to give a voice to what the drawing was intended to convey’ and thereby make ‘parts of the self and / or levels of development visible’.2

Three years later, in 2017, we worked with Maher Alshaki in Amsterdam. During a three-part interview that we documented and which resulted in the video Maher’s Groundplan Drawing (2017), Maher told the story of his family home in Al Nabek, Syria, while drawing it. Through repeated iterations of the drawings and lengthy elaborations of specific stories, he explained how the structure and use of his home was affected by the events of conflict. Many homes were transformed from living spaces into adaptable survival shelters. Highlighting specific moments and events in the alteration of one man’s domestic space provides more tangible insight into how Syrian homes underwent upheaval.

Memory Journey

Memory-recall methods typically use architectural space as an aid for memorisation. The ‘method loci’ requires committing to memory and recalling complex sequences observed along a specific spatial ‘route’.3 This method makes use of spatial recognition or association, which is known as the ‘memory palace’ or the ‘memory journey’. Such methods are used for memory competitions, testimonial statements and witness recollection of events. The ‘cognitive interview’ is a method used by police officers to ‘return to both the environment and the emotional context of the scene of the crime’.4

Space and conditions of architecture play an essential role in the recognition of events that initially seem to be forgotten. Ghalia recalls her arrival as a refugee in the Netherlands and, as part of her immigration questioning process, being asked to make a drawing of the location of her home in Damascus and its proximity to other places in the city in order to verify her case. The drawing may not have been accurate enough to function as geographic verification; the unrehearsed drawing exercise was rather, a way to test if ‘truthful’ memories can be instantaneously recalled.

Remains of a Home

Omar & Marwa’s Groundplan depicts an apartment in a suburb of Damascus as remembered by Omar and Marwa from their childhood. When the Syrian conflict started, the home owned by their father was uninhabited until he decided to rent it out to a family in need. In 2012, a shootout between military forces and an unknown gang took place inside the apartment. The apartment was destroyed during the incident and men from both groups were murdered inside it. Omar returned to the home after the incident to clean the devastated apartment. Even after the bodies had been removed, evidence of blood, broken structures, cracked windows and shattered furniture remained.

The ruins of the family’s apartment bears witness to the events that took place there in 2012. The writings of architectural and anthropological researchers Andrew Herscher and Yael Navaro-Yashin are helpful in highlighting important aspects connected to the post-conflict understanding of Omar and Marwa’s home.

Andrew Herscher is an expert in architectural forms of political violence, particularly in relation to the Balkan conflict. In an interview with Eyal Weisman, director of research at Forensic Architecture, he outlines the pitfalls involved in using post-conflict architectural ruins as conclusive evidence of the intentions and power dynamics of those involved in conflict.5 To illustrate this, Herscher recalls a case he researched in Kosovo for the International Criminal court in The Hague. The investigation included proving that the strategy of Slobodan Milošević involved deliberate targeting of mosque buildings during the Serbian conflict. (The ICC sought evidence to prove that Milošević’s actions were proof of religious persecution.) Herscher researched the destruction of mosques and other religious buildings, which opened up questions and doubts regarding the limitations of the tribunal’s axis of interpretation. To Herscher it seemed that the tribunal was focussed on proving authorial responsibility or the legally liable proponent of mosque destruction rather than taking into account the ‘ensemble of individual, collective and non-human forces’, which are also at play within the conflict situation at large.6 The ruins of post-conflict architecture provide important clues regarding what has occured on a specific site – but they do not take into account the complex network of human and non-human influences on the situation.

In the case of Omar and Marwa’s apartment, their family arranged appropriate paperwork for the renting out of their home to an approved renter, which was luckily recognised by authorities. Owning an apartment in which an anti-regime gang lived directly implicated their family. After the apartment was cleaned, the destruction of the walls and interior of the now-abandoned apartment remained as proof that the event took place. Still, the complex network of parties involved in the determination of truth and justice surrounding the incident depends on who narrates the story.

I consulted Navaro-Yashin’s ethnographic research in ‘Northern Cyprus’, a post-conflict region carved out as a separate (de facto) state since its invasion by Turkey in 1974. Many abandoned Greek-Cypriot homes and villages in this region are still inhabited by Turkish-Cypriot families. Navaro-Yashin uses theory and anthropological research to understand the impact and effect that is experienced in personal spaces. Cypriot houses that have been abandoned, changed hands and been appropriated by refugees provide us with another notion of the house. ‘Here’, writes Navaro-Yashin, ‘there is uneasiness between a person and his dwelling, a conflict, anxiety’.7

Drawing on the work of philosophers such as Bruno Latour and Gaston Bachelard, Navaro-Yashin argues for an understanding of personal subjectivity that focusses on the experience of the individual and the profound influence of non-human objects, such as the home and its domestic objects.8 Navaro-Yashin’s description of Cypriot houses introduces many parallels to the abandonment and repossession of homes in Syria. According to Navaro-Yashin, the house can be considered ‘a political and legal institution’ charged with ‘politically and legally induced affect’.9 Despite regional specificity, the remains of an abandoned home in times of conflict represent a convergence of external forces and interests imposed on a personal space.

Through the Groundplan Drawings project, we continue to invite participants to document their rich experience of a lost home through drawing. In many instances, the captured memory is trapped in an undetermined moment in time. Working closely with participants to narrate drawings exposes valuable details and gives unexpected entry points for better understanding and sharing the layered and complex lived experience of conflict.

Foundland Collective aims to document and contextualise stories such as those that emerge in Groundplan Drawings to open new avenues of empathy and shared experience in a manner that provides alternatives to mainstream reporting on conflict. By collecting and creating subjective and experience-based documents about personal spaces and architecture, multiple narratives, perspectives and interpretations emerge. Doing so nurtures a growing archive that may not have otherwise left a trace.

1. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, From Palestine to Israel: A Photographic Record of Destruction and State Formation, 1947–1950, London: Pluto Press, 2011.

2. Claudia Mitchell, Ann Smith, Jean Stuart and Linda Theron (ed.), Picturing Research: Drawing as Visual Methodology, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2011.

3. Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, London: Routledge, 1966.

4. Magali Ginet and Jacques Py, ‘A Technique for Enhancing Memory in Eyewitness Testimonies for Use by Police Officers and Judicial Officials: The Cognitive Interview’, Le travail humain, vol. 64, no. 2, 2001, pp. 173–91.

5. Eyal Weizman and Andrew Herscher, ‘Conversation: Architecture, Violence, Evidence’, Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism, vol. 8, pp. 111–23.

6. Ibid., p.119.

7. Yael Navaro-Yashin, The Make-Believe Space; Affective Geography in a Postwar Polity, London: Duke University Press, 2012, p. 191.

8. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, New York: Penguin, 2014, p. 121.

9. Navaro-Yashin, The Make-Believe Space, p. 197.

Lauren Alexander (1983, ZA) is a designer and artist. She teaches in BA and MA Graphic Design at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK) and in 2019 she was a member of the KABK Research Group chaired by Alice Twemlow. Her collaboration with designer Ghalia Elsrakbi (1978, SY) initiated in 2009 has informed her practice and teaching. As Foundland Collective Lauren and Ghalia explore under-represented political and historical narratives by working with archives via art, design, writing, educational formats, video making and storytelling. The duo critically reflects upon what it means to produce politically engaged work from their position as non-Western artists working between Europe and the Middle East. Foundland Collective was awarded the Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship for research in the largest Arab American archive in 2015, the outcome of which was presented as a video installation at Centre Pompidou in Paris (2017) and their short video, ‘The New World, Episode One’ premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival (2018). The duo have lectured and exhibited internationally including at ISPC, New York, Ars Electronica, Linz, Fikra Biennial, Sharjah and Tashweesh Feminist Festival, Cairo and Brussels. Their work has been shortlisted for the Dutch Prix de Rome in 2015 and Dutch Design Awards in 2016.