Musing Map

November 1, 2009essay,

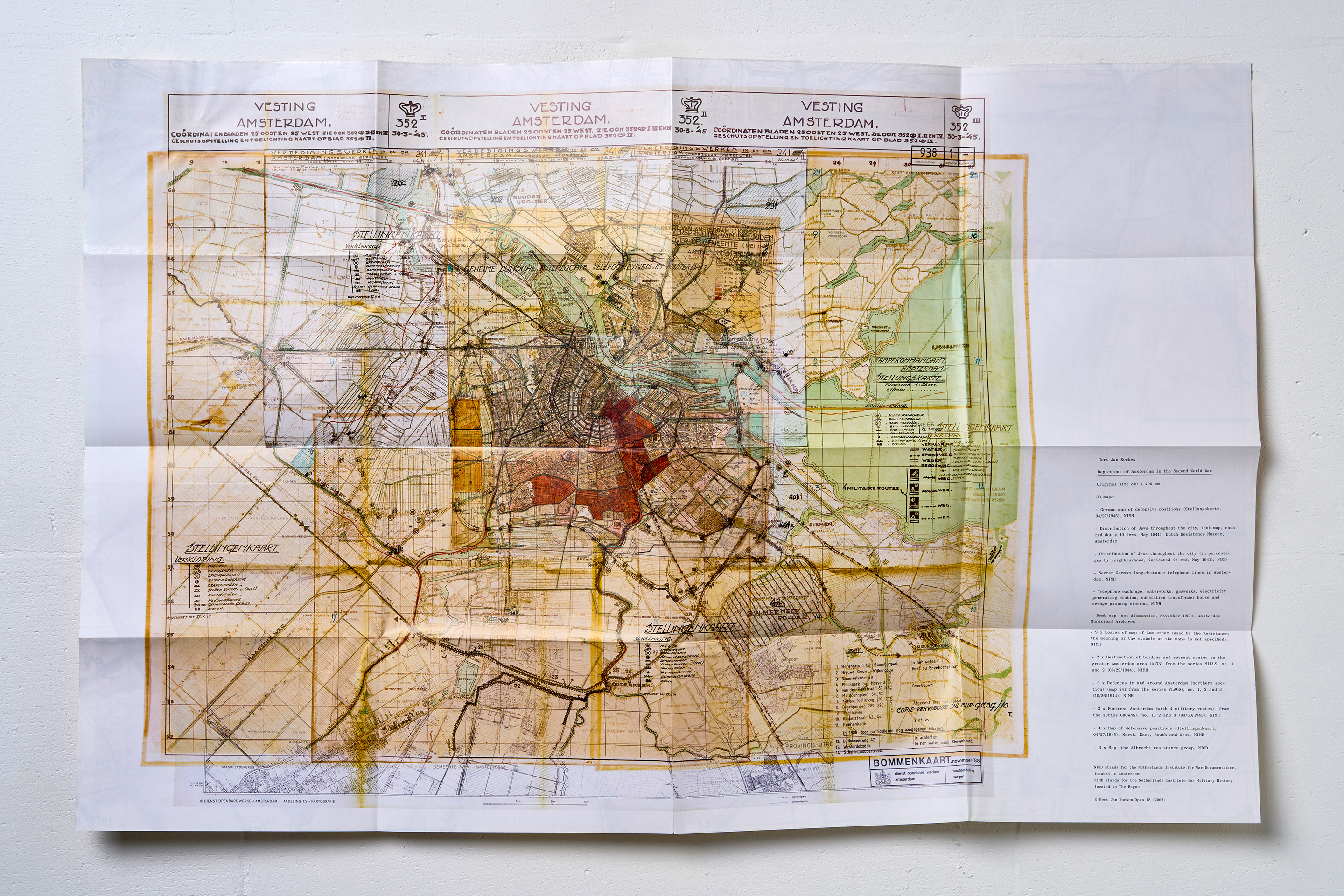

An introduction to the art contribution to this issue by Gert Jan Kocken, which is included as a loose supplement titled Depictions of Amsterdam in the Second World War. This article is partly based on Bianca Stigter’s De bezette stad: Plattegrond van Amsterdam 1940–1945 (Amsterdam: Athenaeum Polak & Van Gennep Publishers, 2005).

On 15 May 1940, German soldiers of the 39th Army Corps entered Amsterdam over the Berlage Bridge. Photographs of that entrance have been preserved. In one of them, you can see a map of Amsterdam. A municipal civil servant is standing with it in front of the City Hall on the Oudezijds Voorburgwal. It is a large map, wider than two men and half as high. At the top are two little strings, as if it has just been taken down from the wall. The map was being offered to the German commander so that he could familiarize his troops with the city. A map as a gift – as if the city had rolled onto its back like a dog, saying: go ahead; here are my canals and squares, my hospitals and churches, my barracks and offices, my water and land. Take them.

Nowadays such a gift would no longer be necessary; Google Earth reveals much more than a map of Amsterdam at 1:10,000. In addition to the Internet, we have tom-tom and a company like kaartopmaat.nl. I quote their website: ‘As a municipal civil servant, you know how important it is for your city to be accurately mapped out. Literally. Not only for yourself, but especially for the residents of your city. We will gladly help you create a folding map that is precisely tailored to the demands of your city. You can – if you wish – make certain information on your city map stand out extra strongly. For example, all of the government agencies, other public buildings such as libraries and theatres, garbage collection district boundaries, public transportation routes, etcetera. You can also show the opening hours of City Hall, important telephone numbers and websites on your map. The municipal coat of arms? No problem. Whatever you want!’

Whether it was necessary back then is debatable. Amsterdam was not terra incognita in 1940. Fall Gelb, as the oft-postponed invasion of the Netherlands and Belgium was called, had an Oberquartiermeister. The German army had its own maps of the Netherlands at the scales of 1:50,000 and 1:25,000. And naturally, Dutch maps of Amsterdam could simply be purchased. The Germans took advantage of their bridgehead in the city to quarter their troops. On 17 May, the Ortskommandantur, the local command, moved into the German Consulate on Museumplein, the building in which the American Consulate is now located.

Today’s map of the centre of Amsterdam resembles the 1940 map of the centre of Amsterdam. The half-moon of the canal belt is still the same, the Jordaan area is still the Jordaan, the royal palace still stands on the Dam. Unlike Rotterdam or Arnhem, Amsterdam survived the war relatively unscathed, outwardly. The city was bombed only a few times. Nor did much construction go on during the five years of occupation. Perhaps that’s what is so amazing: the ‘decor’ was already there and it’s still there now. Anne Frank’s hiding place on the Prinsengracht, the Achterhuis (The Annex), was built in 1740. Today, you cannot tell by looking at it that the volunteer auxiliary police were headquartered in the first public business school on Raamplein in 1942, that there was an eating place in the Derde Weteringdwarsstraat for members of the Dutch Resistance’s Reen courier service during the Hunger Winter, that Willemsparkweg 186 was the regional headquarters of the youth branch of the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands. To name just a few.

You can no longer tell by looking at it, neither at today’s reality nor at the map of what was once reality. Yet historical maps can give you an impression of what was important at the time. Here’s another quote from kaartopmaat.nl, where they introduce the concept of the mijmerkaart or ‘musing map’: ‘A historical map of your city, region or province is truly a “musing map”, a voyage of discovery into the past that will give your business contacts great viewing pleasure. A splendid, original and lasting promotional gift.’

During the Second World War, quite a lot of maps were made or re-worked that provided other than the usual information. ‘No problem. Everything’s possible.’ This also seems to have been the mantra of the wartime mapmakers. The most notorious example is the stippenkaart, the ‘dot map’. In 1941, the Municipal Bureau of Statistics put dots on the map of Amsterdam, with each dot representing ten Jews. On another map, the zealous public servants indicated the distribution of Jews per neighbourhood by colour. The redder the district, the more Jews lived there – until 1943, by which time Jews had vanished from the streets, as Böhmker, the ‘Beauftragte of the Reichskommissars for the City of Amsterdam’ described the Holocaust. Members of the SD, the German intelligence service, or other Germans occupied the houses of deported Jews located in the better neighbourhoods. The houses in the old Jewish quarter mostly remained empty. In the Hunger Winter, they were ransacked again, this time by people searching for wood to stoke their emergency stoves. Most of these houses were not rebuilt. There, the original decor is gone. In order to gain a picture of the damage, the Municipal Development Company had the ruins charted on a map of Amsterdam, which afterward was nicknamed the gatenkaart or ‘gap map’.

The Germans also continued to make military maps of Amsterdam and the surrounding area. ‘Not for Public View’ is still written on these maps in German. In 1943, the Germans began getting ready to defend the city against the expected Allied invasion. Amsterdam was labelled a Festen Platz, a city that must be defended to the last bullet. Explosives were put in the dikes. Meanwhile, various resistance groups made maps of the locations of German military bases in the city. Groep Albrecht made an entire album of detailed maps showing all of the schools, garages and barracks that were occupied by the Germans in 1943.

In early 1945, the Dutch Resistance worked out plans for protecting Amsterdam against destruction and armed raids as the German army retreated. The plans included the defence of important facilities such as gas factories and electricity generating stations. The Resistance also charted such things as German telephone lines. Much of this information was collected for the benefit of the Allied forces in England. On some of the maps drawn up by the Resistance, we do not know exactly what is indicated – the red squares and stripes no longer reveal their secrets.

Hanging on a wall in the Ortskommandantur on Museumplein was a map of Germany, on which the German military coloured in red the areas of the Reich that the Allies occupied. By May, there were no more white spots.

Artist Gert Jan Kocken spread 33 different maps of Amsterdam across one another in an attempt to give an overall picture of the history of the city: not only the dispersion of Jews but also the location of bombs that did not explode, not only the Germans’ military defences but also the attempts made by the resistance to map them. A map is never the place itself, but it almost seems that way on this ‘musing map’. Handwritten texts, corrections, sometimes barely legible scribbles, give the maps a materiality that brings the past very close. Even a spot or a scratch is part of this, even these things indicate how people lived and died in Amsterdam. Kocken’s map is so large that such details stand out: it measures 310 x 400 cm.

I quote for the last time from kaartopmaat.nl: ‘In the beginning of the twenty-first century, we can look at the whole world on our computers, for instance with Google Earth. What has not changed throughout the centuries, however, is the human fascination with maps. When you study a map, you jump into in its landscape, as it were. You search a map for strange, exotic lands and regions. With a bird’s-eye view, you trek across high mountains and plains. You follow the endlessly meandering river to its source. Before you know it, the map has you in its grip and hours have passed.’

Replace the landscape with the city, the exotic with the nearby. High mountains are canals, the plain is Museumplein, the Amstel meanders.

Bianca Stigter is an art critic who writes for NRC Handelsblad, among other things. Bezette stad. Plattegrond van Amsterdam 1940–1945 (Occupied City. Map of Amsterdam 1940–1945) was published in 2005.