New Art for the New University

June 15, 2015essay,

In front of the University of Amsterdam Maagdenhuis building there is a red cube. The cube appears to be a foundation, a support structure, for an abstract metal geometric construction that emerges from it. Its constructivist nature may indicate a desire for change and replication – as if the structure is not quite finished, temporarily frozen in its growth process. If this is truly a “monument” for the New University, as Alexander Nieuwenhuis and Rudolf Valkhoff's piece is called, then it is one that seems to doubt its own nature because, rather than commemorating structures from the past, it yearns to imagine the future. It is as if the thousands of students and supporters of the New University who were standing around the red cube they had adopted as their symbol of protest were demanding not only a new university but were also planting the seed for a new art.

The Practice of Occupation

On Friday, 13 February 2015, a group of students from the University of Amsterdam occupied a university building, the so-called Bungehuis, and subsequently the famous Maagdenhuis, which has been occupied more than ten times since 1969, when it was famously declared “Karl Marx University”. The student occupation of 2015 declared itself the New University and demanded the democratisation of the university, direct elections of the internal university board, political and financial transparency, an end to the budget cuts in philosophy and language departments, the university’s real estate speculation practices, and improved adjunct teaching contracts. In essence, it was a protest against university privatisation and commercialisation.

What is crucial about this student occupation is that it is not just a protest, but that the New University is actually proposing an alternative to current practices. The students are currently organising their own studies in collaboration with sympathetic teachers and the student union, which have joined the protest. There are full days of lectures, debates, workshops, film screenings, and reading groups – free of charge to anyone. The New University’s programs and policies are decided upon in daily student assemblies, thus making the old University of Amsterdam into a site of student self-governance. In other words: the students and teachers are performing the university they always desired. They shape a structure of direct democracy and self-governance that creates a space, an imaginary, that allows them to articulate and enact these desires. They are not giving in to the world as it is, but dare to imagine and desire for it to be different, and thus act it differently.

The students never asked for “permission” from the university board to occupy the Bungehuis. They never discussed it with any political parties, they simply occupied a building. In other words, they engaged in what the board considers an act of violence; an occupation that brought the former board chairman, Louise Gunnink to oppose the occupation of what she referred to as “her” university. This perception of a university space as something that is privately owned is the crux of the issue. In fact, occupation was an attempt to reclaim education as common good from the clutches of the bureaucrats and managers. One could even claim that their occupation was an act of self-defence, a reaction to the government’s decision to slash the basic educational stipend (basisbeurs), which would return education to one based on class and those who can afford it.

The establishment of New University through occupation was an act of self-defence that sought to maintain the principle of education as a common good. The New University framed itself as a non-violent movement, which offered obvious strategic advantages, but at its core was the act of occupying as self-defence. Austerity was seen as an act of violence against general society, and as members of that society, we claim the right to oppose the authorities through occupation. The unnecessarily violent expulsion of the students on April 11 proves that our opponents have no hesitancy to affirm their will through power, and we, as those who have decided to resist, will have to find creative means to articulate and practice new, opposing forms of power.

In any case, a single expulsion cannot squash the movement. Over the past few months, the New University student occupation has unleashed a chain of events, with New Universities being established all over the Netherlands – in Leiden, Utrecht, Rotterdam, Maastricht, Nijmegen, and Groningen. But the student occupation movement has also engaged in discussion with other student protests worldwide, from South Africa to Istanbul to London.

The protest symbol, the red cube, refers to the student protests that have taken place outside of the Netherlands, namely the 2012 Red Square student protests in Quebec, which took the lead with their now-famous saying “Être quarement dans le rouge” (“Being squarely in the red”), which refers both to student debt and to the red banner of internationalism. The New University thus recognises that our political and educational interests are not limited to a specific school, city or country, but also addresses the well-being of others who are facing a common enemy. A declaration of cross-border solidarity by protesting against the privatisation of our common, public resources – politics, economics, ecology, education, healthcare, and culture – by corporate capitalist forces is the essence of internationalism. In recognising this common enemy, we are able to make the common internationalist struggle tangible and visible.

The Total Work of Art – Revisited

This issue of visibility brings me to the question of art. During the pro-New University demonstrations in Amsterdam on 13 March, we saw art history students gathered around a banner that read: “Art History is Present”. The question that we as artists now need to address, as curator Vivian Ziherl observed during the protest, is whether contemporary art is present here as well.

During this period, I worked with fellow New University artists, like designer-filmmaker Rob Schröder, who had a prominent role in designing posters and conferences in the 1980s student movement and artist Matthijs de Bruijne, who over the past few years developed work in collaboration with the Dutch cleaner’s union campaign called “Schoon Genoeg”! (“We’ve Had Enough!,” where schoon is a pun that also means “clean”). Together with students from the Sandberg Institute, we explored how artists and designers can reshape their work when they position themselves in the heart of a political struggle. This was an attempt to address the question regarding the New University – what kind of university do we actually want? – by rephrasing it for the art world: in what kind of world do we want to be artists? Do we dedicate our work to make “capitalism more beautiful,” as artist Hito Steyerl has noted, or do we attempt to define our practice in a different political context? What does it mean to be an artist inside the New University compared to being an artist trying to get a painting or sculpture sold at some generic art fair? What is the social project being articulated by the New University, and what should the place of art be in this project?

What is crucial when thinking of our work as artists in the context of social movements such as the New University is that we should not seek to make singular, so-called “autonomous” artworks. A social movement is not a “gallery” in which to exhibit one’s work. Rather, the assembly of participants in this social movement is itself the artwork. What the New University is essentially creating by offering free education and encouraging open assembly is a set of new social relations, a compositional model that assembles precarious forces such as students, teachers, workers, refugees, and artists into a new, political entity. This touches upon the concept of the “Gesammtkunstwerk” (the total work of art) as Joseph Beuys, artist and co-founder of the Green Party (Die Grünen), described it. Despite the fact that his methodology has become known as “Beuysian,” his approach was an attempt to depart from the Wagnerian conception of the total work of art as a model orchestrated by a singular author. His famous dictum – “Jeder Mensch Ein Künstler” (Every Human Being an Artist) was not, however, a call for everyone to become individual visual artists. Rather, Beuys was articulating a new social ecology that applied to the whole of humanity, in which the main value of human life lies not in the domain of labour, but in the collective capital of creativity. The capacity to create, to make worlds, is not limited to the position of the artist alone; it applies to the whole of society.

Beuys saw himself as an instrument for the extension of the domain of creative capital, to connect his authorship to a multiplicity of authors that together create a new ecology of life: the total work of art was no longer restricted to the theatre stage, but could actually be extended to the whole ecology of society. In that context, the quality of the artwork lies in its transformative capacity. Its capacity to engage the collective capital of creativity in each and all of us. In Beuys’s case, it was located in a revolutionary, ecological socialist project. To reconstruct social relationships around common capital rather than the individual privilege obtained from engaging in the rat race that corporate capitalism has laid out for us, was the ideological aim that structured Beuys’s artistic convictions.

The very idea of the New University – the “university within the university,” the “parallel university” – in that light is an intervention in and of itself. It’s a conceptual framework that allows us to rethink the social relationships of common knowledge and the collective right to education. As such, from a Beuysian perspective, it can be considered a collective work of art that performs and thus creates the imaginary of a new university and, through this collective performance, restructures social relations. While we can relate this movement to the Beuysian idea of the total work of art, it also departs from the last remaining notions of authorship in his work, because the New University movement has done everything within its capacity to avoid appointing leaders – singular authors – who could undermine its radical pluriformity. While this position also threatens the possibility to hold the movement accountable for its aims – as everyone is always responsible for everything, which in times of crisis easily turns into no one being responsible at all – the foundation of a broadly carried movement needs an even so broad and differentiated sense of identification.

The Art of the New University

So let’s say that an artist makes a banner, which in art schools is considered as the ultimate horror of “protest art,” a derogatory term that disqualifies art that attempts to engage in political transformation as “activism” and “propaganda.” In this case, I propose to analyse the banner “NIEUWE UNIVERSITEIT – WELCOMES YOU –” (2015), a 17-meter canvas that hung from the roof of the Maagdenhuis. The idea was initiated by artist-student Marleen van der Zanden, but, of course, the banner is not the “artwork”. It cannot be evaluated as merely a singular object or canvas. Its quality lies in its capacity to contribute to the articulation of the common political imaginary that the movement as a whole is trying to bring into being. Nevertheless, Van der Zanden’s endeavour can be analysed in very specific aesthetic terms.

Van der Zanden analysed the front of the building before her intervention and decided that the New University’s aesthetics were first and foremost that of a student protest, not an actual new university. The University of Amsterdam’s logos were still intact and the student banners were simply too small to make an impression on passersby and visitors that a totally new institution had been created. In simple visual terms, the massive building overwhelmed the other student occupation signs and banners.

The very visual nature of the occupation itself already forebodes that the occupiers will ultimately be evicted while the building itself will remain. Thus, this monumental University of Amsterdam site effectively works as an architecture of conservatism. Van der Zanden thus had to first of all engage with the sheer size of the building, her intervention had to be a spatial one that could destabilise its conservative, monumental nature. This resulted in the choice of a very large canvas that could span the entire façade and thus effectively lay a claim on the total institution and transform it into the New University. The building is, in a sense, wrapped around the banner, rather than the other way around. Prior to the banner, the prospects of the New University in visual terms were speculative at best, but suddenly the banner had made it a reality: the New University came into existence because it is borne and performed by students and teachers alike. The banner inscribes this claim into the architecture itself.

The banner thus enforces the imaginary of the New University; it makes a future scenario – the indefinite end of the University of Amsterdam, the beginning of the New University – real in the present. By making this imaginary visual and materially tangible, it becomes something we can relate to: a point of concrete orientation in the tedious struggle of building an institution anew. Moreover, Van der Zanden also decided to not create an overtly corporate identity. Whereas the font of the banner is very readable and meticulously painted, she consciously did not print it, but kept the human hand – the hand of the painter – that created the canvas visible. Thus, she perfectly balanced the need for a legitimate, visual claim on the old university, indefinitely declaring it as the legitimate New University in the present, but remained reminiscent of the fact that the New University is not a corporation that imprints its demands and structures upon its subjects as the current board of the University of Amsterdam does. Rather, it considers itself as a collective creation – one in which human scale, human needs, human sociabilities, are the foundation and not its collateral damage.Van der Zanden seems to be re-evaluating the practice of futurist art because, after all, the New University has yet to be fully born. Meanwhile the imagery she proposes has already declared that it is there in the present. The New Art of the New University is a futurism visualised and acted upon in the present. The New University and its art propose a “utopian performance”, as theoretician Timotheus Vermeulen termed it, which refers back to the famous ’68 dictum: “Be realistic, demand the impossible”. In the case of the New University, this could be rewritten to say: “Be realistic, practice the impossible.”

The artist contributes his or her visual literacy to the social movement, by which we mean the capacity of artists to “read” form. You could say that the space that defines art as distinct from politics is that of morphology, a genealogy of forms. Artists articulate specific sensibilities through form, and they understand that there is a relation between the form in which we organise, the form in which we assemble, the form in which we communicate, and the possibility of political transformation that results from it. We can only act upon this future in the present if we learn to imagine a different future. Art is what connects the space of the impossible to the present; it occupies the space of our political desires and imaginaries, and creates the means for them to manifest themselves in a collective and shared presence. Morphology thus also connects the concepts of past, present and future, allowing different “spheres” of time to become interconnected. In this process, solidarities are created through the overlapping of time – how the students from 2015 engage in a dialogue with the students from 1969. The years of ideological erosion are ultimately discarded, and 1969 re-emerges in the present day. The nightmare of global capitalism that separates the two is discarded allowing a new history to be articulated. In other words, after 1969 comes 2015.

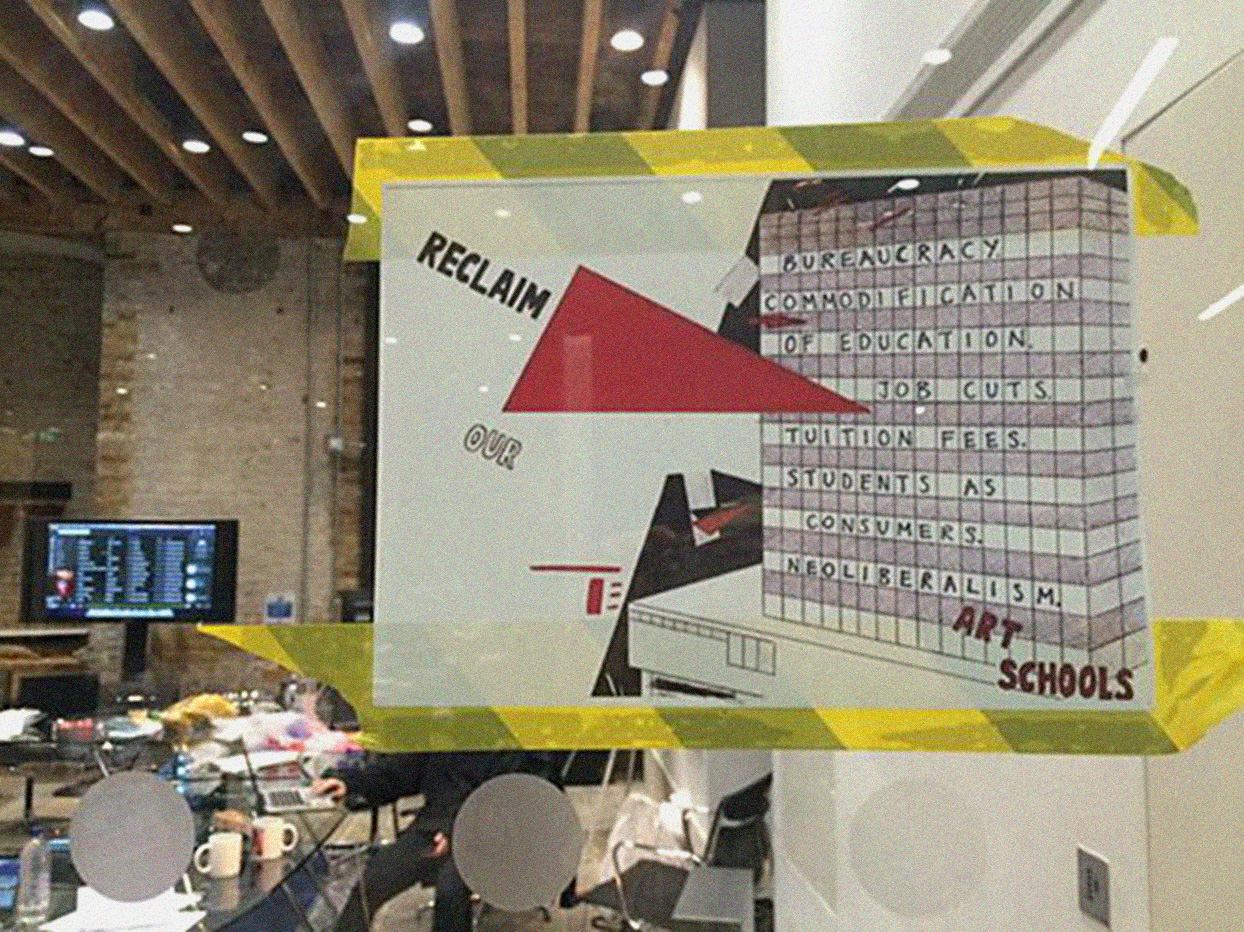

Let’s examine the artwork “Driving a Wedge Through the Corporatized Art School” by Robin Clark, which was produced for the student protests at the Chelsea School of Art in London. The red triangle is seen violating the bureaucratised and privatised art school and refers directly to Soviet constructivist El Lissitzky’s poster “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge” (1920), in which the red wedge symbolises the revolutionary Bolsheviks, who are penetrating and defeating their White movement opponents during the Russian Civil War. Clark has attempted to visually link two different historical struggles. The White Movement, loyal to the Tsar, have become the armies of managers loyal to corporate capital. The red wedge links the two time frames to one another: an abstract shape that represents the revolutionary consciousness of an alliance of peoples, students, teachers, workers, artists, to resist and overcome oppressive structures of power.

The red wedge of the 1920s is the red square of 2015. And in both 1920 and 2015 it was an artist who created it. Let’s keep that powerful truth in mind when we create our New Art for the New University.

This text is a prepublication from a special issue of Krisis. Journal for Contemporary Philosophy on the New University and the student movement.

Jonas Staal is a visual artist whose work deals with the relation between art, propaganda, and democracy. He is the founder of the artistic and political organization New World Summit, which develops parliaments for stateless political organizations, and the New World Academy (together with BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht), an educational platform for art and politics. His most recent publications include Nosso Lar, Brasília (Capacete & Jap Sam Books, 2014) on the relation between spiritism and modernism in Brazilian architecture. He currently finalizes his PhD research entitled To Make a World: Art as Emancipatory Propaganda at the PhDArts program at Leiden University.