Parliaments of the European Union

June 12, 2018artist contribution,

As a conceptual documentary photographer, Nico Bick’s photographic works, often produced as series, invite concentrated investigation. In this work, by focusing on the plenary chamber of parliaments in the European Union, he draws attention to parliamentary history of democracy and its functioning within the EU.

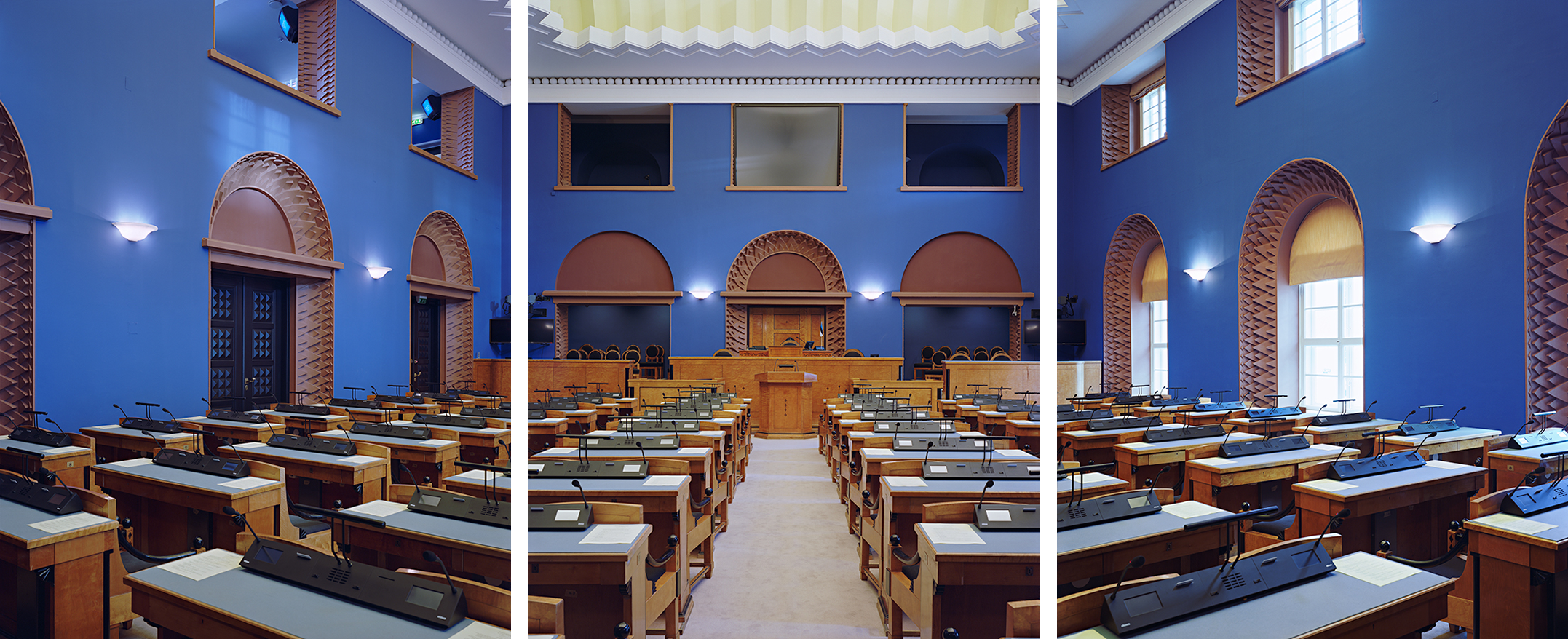

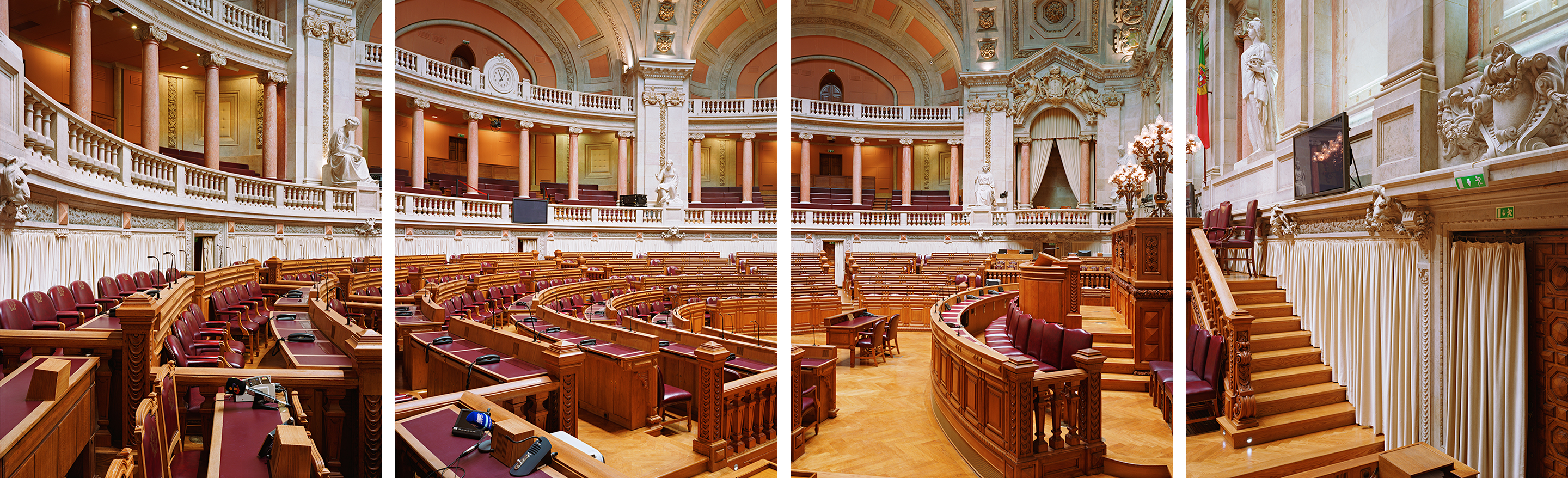

After the (banking) crisis in 2008, it became increasingly clear that unity within the European Union is fragile. As soon as the economy began to deteriorate, the EU and the fiercely fought-for European unity began to crack in many places and even national sentiment reappeared – one reason for Bick to deepen his understanding of one of the most important conditions for EU membership, democracy. His series of three or four photographs captures the plenary chamber of all parliaments in the EU – the twenty-eight member states and the European Parliament in Brussels and Strasbourg. The simplicity of this description stands in stark contrast to the great effort that went into making the series, which took Bick almost six years to complete. He photographed his first parliament in the summer of 2010 and his last parliament in fall 2015. Organizing access to parliaments and travel was a long and complicated process. For example, some parliaments were not easily persuaded to grant him access. In some cases, the access application took more than a year and a half to complete. The photography itself also required great effort, finding the right position for his analogue technical camera and to define the frameworks for his triptych and tetraptychs was meticulous and time-consuming work.

The word parliament is derived from the French parler, to talk. Parliament means ‘negotiating’ or ‘entering into a discussion’. As an extension of this, a ‘parliament’ is also ‘busy talk’ or ‘noisy conversation’. How are these discussions and debates facilitated and does this influence the way they are discussed? For example, can a member of parliament operate the (interruption) microphone from his or her own chair, or do they have to get up and walk to a shared microphone? Is this microphone close to them or must they step forward as in the Dutch parliament because the interrupting microphones are positioned directly in front of the government’s cabinet?

With Parliaments1, Nico Bick takes a radically different position from that usually taken by the media. Social media has dramatically increased the proliferation of ephemeral images and journalism. Over the last decade, there has been a deluge of images of daily hype with edited images and fake news becoming increasingly prevalent. In framing and precisely positioning cuts between the photos, Nico Bick, instead, guides and intensifies the act of looking. The images are unlocked by the framing, sharpness and exposure of information commonly hidden. As in his other works there are no people in the photographs. By focusing on the space itself, the traces of use become visible, almost tangible. Not people, but space tells the story. Per country, per parliament, you can read the history and ongoings of parliamentary democracy in the architecture and layout begging the questions: what furniture, colours, materials and art have been used in the rooms and what role does daylight play? Nico Bick places the viewer in the middle of the room, something forbidden for those who are not parliamentarians themselves in almost every chamber. The viewer gets a view from within, unlike more traditional portrayals of these spaces, with photographs at a distance and taken from above given the press’s distance from events.

All thirty parliaments are presented in the same large format, revealing their similarities and differences. Is the chamber horseshoe or semi-circular? In the Danish, Spanish or European parliament in Brussels and Strasbourg everyone has their own seats, while the French and British parliamentarians have to share a bench. At busy meetings, people are almost on top of each other. What influence does this have on the people and debate? While one country decorates its parliament with national symbols and works of art, another country opts for neutrality. Plenary chambers of older EU member states often look like living rooms, while many chambers of new EU member states have a technocratic business-like appearance. The Slovenian Parliament is housed in the former headquarters of the Communist Party and has commissioned Slovenia and Lithuania to design a new plenary chamber. Lithuania opts for an almost anonymously neutral look as Slovenia chooses a (democratic) round chamber made of locally sourced wood and natural stone. One country might have the European flag in addition to the national flag and others do not. The parliaments of northern EU countries have mainly cool colours and a crisp design, while southern EU countries adorn themselves in warm colours and resemble theatres.

Parliaments2 provides a window into the EU’s parliamentary history in order to draw the general public’s attention to the functioning of democracy and the strength of elected parliament. Indirectly, Nico Bick establishes a position on information provision, truth finding and taking a stand, literally and figuratively. The triptychs and tetraptychs of the thirty parliaments say a lot, individually and in relation, providing the viewer with tools to uncover layers of information and reflect on the role and function of democracy.

1. Parliaments of the European Union appears in the exhibition Europa. What Else?, shown in 2017 at Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam (28 January – 8 May) and at Atelier néerlandais, Paris (21 September – 18 December).

2. Nico Bick is also preparing a publication. In Nico Bick. Parliaments of the European Union the triptychs and tetraptychs of the 30 parliaments are shown on large fold-out pages. Frits Gierstberg (curator Nederlands Fotomuseum) and journalist and anthropologist Joris Luyendijk have written an accompanying essay. In order to provide room for reflection and comparison, additional information about each country and parliament is included in the post-work, processed into lists and maps. The publication is designed by Joost Grootens. The price is EUR 69 euro. You can already subscribe (with a 10% discount) at www.nicobick.nl.

Nico Bick studied photography at the Royal Academy of Art in the Hague. As a visual artist he investigates the use of (public) space. Characteristic of his early work is a preference for inconspicuous places that appear to be so familiar that nobody seems to notice them anymore. Nowadays he directs his view at spaces with a tangible tension between the public and the private domain. In a time in which everybody can produce digital photos easily, Bick feels a strong need for an uncompromising analogue approach. With patience and careful observation he creates, together with a large format camera, series’ of highly detailed images to focus the attention on both the space – in the absence of its users – and the meaning of the places he photographs.

Ingrid Oosterheerd studied architectural history at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. She works as an independent author, researcher and (image) editor on books, magazines and exhibitions about architecture and urban planning. From 1992 to 2000 she worked at the Netherlands Architecture Institute in Rotterdam, alternately for the exhibitions and collection departments. From 2006 to 2010 she was a member of the editorial board of Stadscahiers. De transformatie van de bestaande stad. Currently she is architectural historian of the Committee on Spatial Quality and Heritage of the municipality Gooise Meren.