Second Opinion. Over beeldende kunstsubsidies in Nederland

December 31, 2007review,

Lex ter Braak, Gitta Luiten, Taco de Neef and Steven van Teeseling (eds.), Second Opinion. Over beeldende kunstsubsidies in Nederland, NAi Publishers, Rotterdam, 2007, 128 pp., isbn 9789056625252

A collection of essays by the French sociologist of art Nathalie Heinich was translated into Dutch and published a few years ago, under the auspices of her special professorial chair, on behalf of the Boekman Foundation. It was not particularly in honour of the Dutch context that the book was given the title Het Van Gogh-effect (The Van Gogh Effect). At the time, Heinich had been obstinately hammering away for several years at a sociology of art that relies strongly on the 'Van Gogh model'.

Her more recent book, L' élite artiste. Excellence et singularité en régime démocratique (2005), uses much the same model. In reading Second Opinion, I was constantly reminded of the contents of L' élite artiste . Allow me to say a bit about it. The thesis that Heinich defends has it that Vincent van Gogh fulfils the function of a hinge between the academic system and modern art. What's more, even today his life and, in particular, his career represent the ideal model for an artist – the image of the artist who is almost completely unrecognized during his lifetime but goes on to enjoy the utmost fame long after death. In other words, a lack of recognition during an artist's life is supposed to guarantee his reputation as a great master in the future. According to Heinich, Van Gogh's legacy is an art world characterized by a singular regime in which uniqueness, authenticity and even excess are regarded as important values. Such a world is diametrically opposed to the dominant political model, democracy, which Heinrich says is not a singular but a collective regime with equality and anti-elitism as its core values. Thanks to its aristocratic heritage, the art world regularly conflicts with the political and social contexts in which it exists today. Because of his exceptional talent, says Heinich, the artist is, in fact, elitist.

Criticisms of the Dutch system of art subsidization expressed by various authors in Second Opinion fit easily into the tense relationship between the exceptional/aristocratic situation and the democratic regime of values. The present system is seen as being too democratic. Prevailing policies are not really conducive to artistic quality. Quality, after all, demands greater selectivity rather than consensual decisions by committees. On the other hand, one important legitimation of the current system is that one cannot know today what the talent of the future is going to be. And so we 'let a thousand flowers bloom'. Such an argument can indeed be cited as a Van Gogh effect. What's worse, the Dutch subsidy system seems to be suffering from a genuine Van Gogh syndrome.

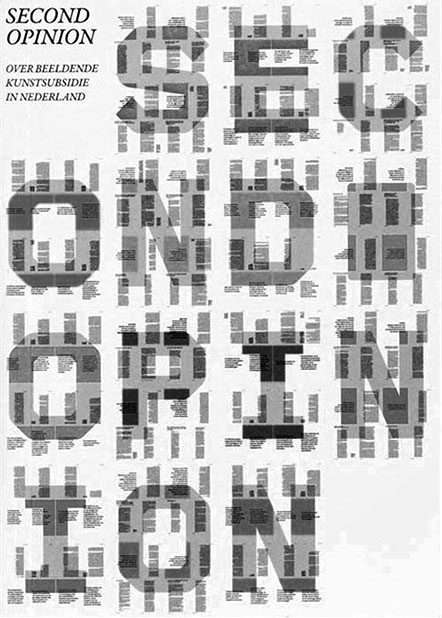

Perhaps it is indeed because of the art world's singular regime and elitism that there is so little debate. Public discussion is one of the more important democratic and thus non-aristocratic traditions. It is surprising that Second Opinion was not initiated by artists or other cultural actors. On the contrary, it is the director of The Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture and the director of the Mondriaan Foundation – Lex ter Braak and Gitta Luiten, respectively – who have set the cat among the pigeons. This is not only peculiar but also courageous. It testifies at least to a proper degree of self-reflection. As becomes a good democracy, Ter Braak and Luiten conclude their book only after they have allowed a motley crowd – as colourful as the design of the book – of curators, gallery owners, museum directors, artists, academics and other interested parties to have their say. In their view, there are three lessons to be drawn from the discussion that they themselves have generated: a better balance should be found between subsidizing supply and demand, which in practice means more money for institutions; there should be higher subsidies for fewer artists, and therefore more selectivity in favour of excellent talent; and Dutch art should become more international.

Although I wholeheartedly endorse the conclusions, I cannot help but wonder whether they were predetermined by the initiators. In the book I recognize both supporters and opponents, to be sure, although the latter are noticeably in the minority. Only one or two, for example, dare to state that the Dutch subsidy system is not bad at all, that Dutch artists are often to be seen abroad, or that the quality of their work is actually very good. They also contradict and at the same time put into perspective the jeering quip one sometimes hears abroad about the artist who is 'world famous, but then only in Holland'. Second Opinion unfortunately lacks any empirical data that would support or deny such a theory, unless we regard Elsevier 's top hundred artists as scientific evidence. No, Second Opinion remains a book of opinions, many of which regularly overlap and, in a few cases, contradict one another. The reader all too quickly ends up in a game of 'tis not! 'tis so! Who is in the right and has good reasons for being so?

Indeed, a democracy asks for a debate before decisions are taken, and such a debate is conducted, or at least staged, in Second Opinion . It remains to be seen what the next steps will be. After the proffering of motley opinions, it is time to make clear, well-grounded choices. That's why this book needs a sequel, a thorough study about the real impact of the Dutch subsidy system, preferably in comparison with a few other countries. Then the question can be posed as to what position Dutch art wants to assume within the global art world. Does it want to internationalize simply so that it can run with the fleeting global trends in art? Or should it aim at an identity of its own, with its own accents that are deemed of value from a cultural and artistic point of view? Do we want an Amsterdam version of Guggenheim Bilbao, or is the Serralves Museum in Porto a better model? Do we want artists who quickly make their mark in the international media and just as quickly burn out, or do we want them to develop lasting international careers? Do we want an art world that sails the globe or one that is anchored in the 'glocal'? In other words, a policy that invests more in institutions, deals more selectively with subsidies to artists and internationalizes in a better way can leave plenty of room for manoeuvring. Only when a clear view of such matters has been developed can we look forward to a vigorous 'First Decision'.

Pascal Gielen is full Professor of Sociology of Art and Politics at the Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts, University of Antwerp where he leads the Culture Commons Quest Office (CCQO). Gielen is editor-in-chief of the international book series Arts in Society. In 2016, he became laureate of the Odysseus grant for excellent international scientific research of the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders in Belgium. His research focuses on creative labour, the institutional context of the arts and cultural politics. Gielen has published many books translated in English, Korean, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish and Turkish.