Setting Limits and Overstepping Limits

Concerning Moniek Toebosch’s Work

November 1, 2005essay,

Image and sound in Moniek Toebosch’s oeuvre are like Siamese twins; even in projects which seem initially to consist solely of sound, the surrounding countryside may for instance serve to heighten the experience of the sound. Loudspeakers are never deployed neutrally, but are presented in a dramatic setting. Brigitte van der Sande spoke to her about art, sound and open space, about overstepping limits in cultural institutions and setting limits for art in public space.

When, years ago, Moniek Toebosch told her father, composer Louis Toebosch, that she wanted to make installations, he said: ‘You’re not a plumber, are you?’ Strictly speaking he was right, but she does not think it is a bad comparison. ‘I link up various media like a network of cultural products.’ In fact, Toebosch’s pursuits are hard to pin down: she is a singer, actress, director, theatre- and film-maker, visual artist, sound artist, composer, activist, webmistress, angel and, for the last year and a half, the director of DasArts, a post-graduate course for theatre-makers.

The public never plays a passive, ‘receiving’ role with Toebosch, but is part of the work itself, gets the work going, is invited to supply material for, or is itself the subject of a work. Although Toebosch has violated many taboos in the arts world in performances and exhibitions, she is always aware of her role as an artist when a work enters the public arena. The fact that she feels just as much at home in a theatre, museum or concert hall, on television or somewhere in the city or the countryside, stems partly from a desire to work in varying conditions, but especially from a need to react to questions she is asked in ever changing situations.

Art in Public Space

Toebosch argues provocatively that art in public space should preferably be invisible or barely audible. Yet she has created many works, some temporary, some permanent, in public space. Engelenzender (Angel Transmitter, 1994), invisible, and deVraagmuur (Questioning Wall, 2001), inaudible, are typical of Toebosch’s approach to work in public space. The former can only be experienced in the private space of your car on the public highway; the latter is, admittedly, ‘there’ visually, but silently seeks attention. Both works take place more in your mind than in actual public space. ‘I believe you should, in principle, always be able to avoid an artwork in public space. I think there are limits to what people should or can accept in that respect. With sound it’s very easy to overstep the mark. There is a limit to sound infiltration in public space.’

Engelenzender was commissioned by the Prof. Dr. Van der Leeuw Foundation and in 1995 Toebosch was awarded the Sandberg prize for the work. ‘Design a bus shelter where contemporary society is very much in evidence’ were the instructions. The radio transmitter could be heard, on fm 98.0 Mhz, from 1994 to 2000, 24 hours a day, along the dyke linking Enkhuizen and Lelystad: rarefied, celestial singing that convinced even the biggest unbelievers that angels do exist. Toebosch considered the location for this sound work – a narrow, raised motorway with the lake of IJsselmeer on either side and, more especially, lots of sky – to be empty enough to be filled with singing.

As a counterpart to Engelenzender Toebosch made an electronic questioning wall – deVraagmuur – for the municipality of Breda in 2001; it is accessible on site, on the façade of the Central Library, and on the Internet. The website www.deVraagmuur.nl presents the wall as a repository for questions, as a counterpoise for so many answers and opinions. Everyone can pose philosophical, poetical, political and personal questions anonymously in public, but the deVraagmuur itself provides no answers. ‘The deVraagmuur is complete silence, although it does make a lot of “noise” in the small street at the library. I drove past it in the car recently because someone said it wasn’t working. At that very moment the question was being asked: what are you doing in this street? I thought, I’m only checking if it’s working. It’s very strange the way it works. It’s fantastic.’ All the questions first go to Toebosch. ‘It’s a lot of work, I edit it and put the new questions on the website. Some of the questions I consider interesting can be repeated, like: “what time is it?” It’s never a mistake to wonder about that. Or: “when were you last in love?” Always a good question, so that stays.’

All Toebosch’s sound art products in public space are temporary forms, which can for instance only be heard during the summer holidays, so they do not annoy the neighbours. ‘I believe far more thought should be given to the length of time an artwork can be left in public space. Even if an artist claims it is about his own individual expression, the topicality of most works soon diminishes, and, to my mind, that is a big problem. My generation has been brought up querying the limits of what is permissible. I believe those limits should also be stretched or shifted. But, there should be a few strict basic rules, for example that an artwork should be “restrained”, not pushy, and not irreversible. The best thing is for an artwork to reveal itself slowly, like the gable-stones on Amsterdam houses. Only monuments should be very prominent: they are intended to remind us of things we should not forget. Jean Nouvel said: “I am not an artist, I am an architect, and I must take my surroundings into account”. Perhaps we should rid ourselves of the term artist when dealing with a work in public space. The term “applied artist” conveys your responsibility better. Not only artists, but also committees and principals should give far more thought to how an artwork functions in public space. The client should indicate the limitations; we’re all far too scared to do that.’

Experiment

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Toebosch studied fashion, graphic design and film at St. Joost Academie in Breda, interrupting those courses for two years at the conservatory. In the following decades she developed these visual and musical foundations into a versatile oeuvre, repeatedly wondering to what she should commit herself, temporarily. Toebosch’s first year as an independent artist, the eventful year of 1969, was a benchmark for her further career. That was the year she met curator Domien van Gent, film-maker Frans Zwartjes, and became acquainted with the work of the American composer John Cage. ‘I think the most important thing for your growth is to meet the right people or get to know their work. I always encounter people at the right time, enabling me to go off in a new direction.’ The confrontation with John Cage’s work put her on a fresh track, musically. ‘For me, Cage signified liberation in how you can work with music, in the resources you apply. Cage liberated my singing. Not that I devoured his book Silence, I was mainly inspired by the various opinions about his work; but I did start experimenting with song, producing strange sounds, screaming, shouting. And improvising with more and more people, not controlled improvisations, but starting from nothing, sometimes from a word or perhaps from a mood or a silence, entirely “à la Cage”.’

Van Gent invited her for her first live audio act – the word performance didn’t exist then – and introduced her to Frans Zwartjes, who asked her to act in his underground films Eating, Spare Bedroom, Seats Two and In Extremo. From Zwartjes she learned to exploit the chemistry between actors. Thanks to him, she acquired a better understanding of the complexity of theatrical and film images. Together with Lodewijk de Boer and Zwartjes, she made music for several of his films.

Toebosch also met Michel Waisvisz and performed with him. Whereas Toebosch explores her body as a sound box, Waisvisz searches for the limits of his body as an electronic translating machine. ‘It really was a wonderful combination. We performed as a pair that tells stories and openly wages war together. A musical battle of wills: who will do what first, who’s is it? We had to work everything out first, what you believe, what you want to convey, what relationship you have with the audience. Michel explored the use of electronics in culture, how to make electronics as human as possible. The fact that it doesn’t take place through all kinds of shiny equipment that looks remote, but that it is actually very directly related to the body and reacts to the body, like the Kraakdoos and the crackle case that he developed at steim, the Studio for Electro-Instrumental Music in Amsterdam. It was primarily intended to look like technology “povera”, electronics in cigar boxes. We both grew up musically in that period.’ From 1972 to 1983 they appeared together for instance in the ‘Moniek & Michel + Michel & Moniek Show’, a live musical performance, in which jazz, blues, opera, electronic music and all manner of audio and theatre forms generated explosive and confrontational improvisations.

Comment

Toebosch also performed on her own, for example in 1978 in the solo musical programme ‘They say she’s a singer’. In these performances Toebosch explored the limits of singing and toyed with the various realities of the stage and life outside it. ‘I had had singing lessons, but couldn’t take myself seriously when I had to learn Mozart’s Das Veilchen. But I was interested in the fact that when you sing a song you have to empathize. For instance, you tell yourself: this song is about a 35-year-old woman whose husband has just died. I was incredibly fascinated by the expression of that in sound and emotion, and the concomitant metamorphosis in the voice. During those performances I also examined what happened when the audience looked at Ms Toebosch singing a song with a thread hanging on her dress. All the audience sees is that thread. For me, every performance was a game with the audience. I started off singing a song about the first sentences we learned in French: “Papa fume une pipe, le chat est sur le piano”. Added to which, I often sang about the audience, if, for example someone arrived late: “ils sont arrivés trop tard, mais évidemment le garage était fermé”. And having bombarded them with difficult music, I would literally say and now I suppose you’d like to hear a really beautiful song? So at the end of the solo I sang for them A Beautiful Song. It was in fact a comment on the classical “lied” recital. It was about coming on stage, concentrating on deportment and, of course, good singing. Normally you are accompanied by a pianist, but in this solo the musical accompaniment was pre-recorded on tape. I was in fact accompanied by Kees Klaver, who was my stage manager and my indirect accompanist, because he was in charge of the switches, lights and sound. He could stop the tape if he thought I wasn’t doing a good job, or turn off the microphone if the performance was not stimulating. That happened occasionally and it made for very strange interaction, the power of the sound, the switches and my own ability and inability to react. For me, that was the real material I was working with.’

In 1983 Toebosch made four live television programmes for vpro broadcasting corporation in collaboration with the Holland Festival; their title, Aanvallen van Uitersten (Attacks of Extremes). The Aanvallen, with the themes Romance, Aesthetics, Technology and Language, formed Toebosch’s attack of tasteless productions on television, or as Toebosch put it: ‘the crude entry causing a minor upset in the decency and standards compartment.’ Four evenings of ‘Gesamt’ theatre with musical renderings, poetry, performances, dance and fashion shows on the Carré theatre stage, directed by Toebosch. Ten minutes before the end of the first live broadcast the Omroep orchestra, directed by Ivan Fischer, walked out on account of Glenn Branca’s deafening rock music preceding the introduction to Liebestod from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, and the accompanying giggles it produced in the audience. Toebosch impressed friend and foe by proceeding with a considerably reduced orchestra to conduct and sing the extremely difficult Liebestod solo.

Visual Art

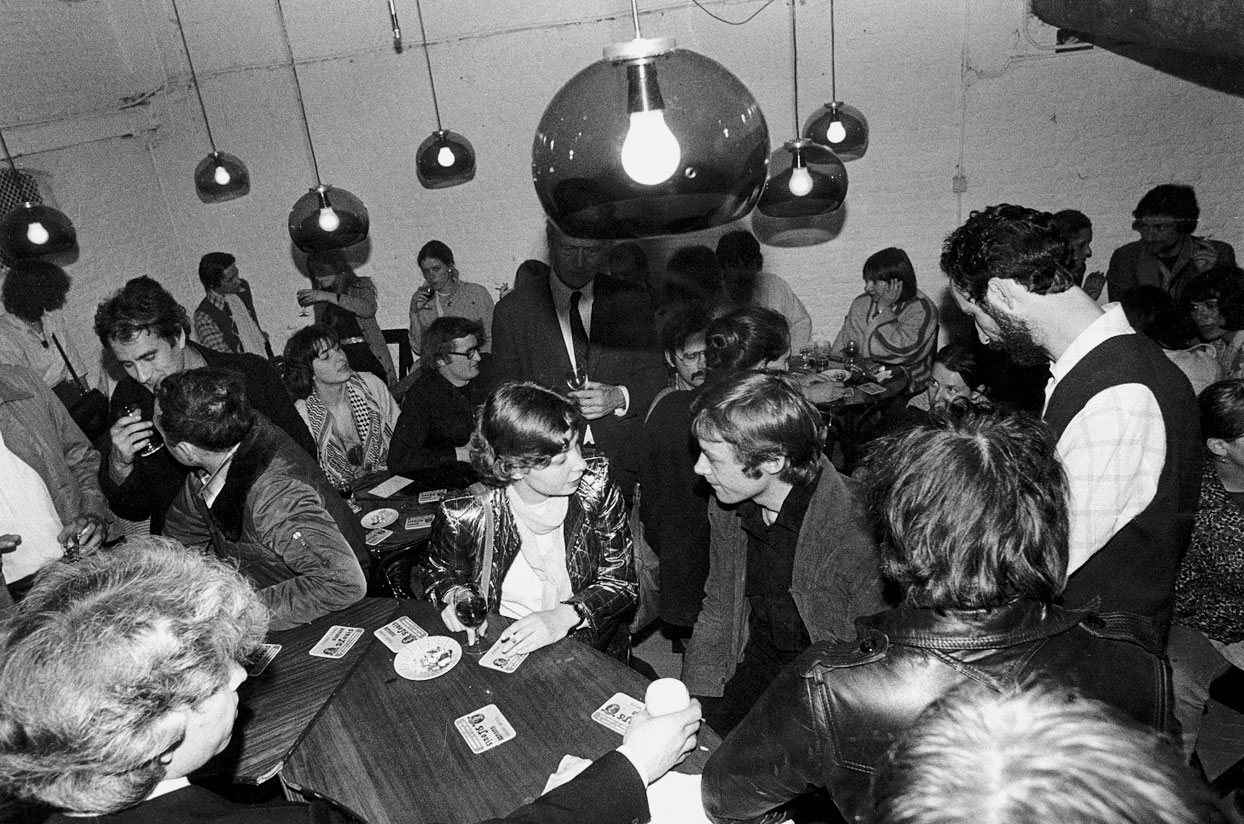

Back to 1978, when Wies Smals invited Toebosch to make a work for the De Appel foundation (currently Centrum for Hedendaagse Kunst De Appel in Amsterdam, ed.). ‘It was a highly crucial moment for me, because I was in the throes of wondering what to develop next. Did I still want the fleeting nature of theatre performances? I found the visual arts attractive because they were so “limited”, because the possibilities and means of expression appeared to be chosen much more carefully. In the theatre, I was guided primarily by emotions.’ Nevertheless, the invitation from Smals also generated an emotional work, though this was in the context of art. ‘I arranged De Appel’s performance area as a bar, because usually, after a performance, everyone moved to the bar round the corner and they always had a big party there. I wanted to have that party in De Appel. The atmosphere there was always deadly serious, almost sacred. I wanted to take the post-performance commonplace feeling into the art “palace”.’

Toebosch recorded the din in other pubs and played it. The right mood was created right away, it was busy and a lot of people were smoking. There was a direct connection via a microphone to the street with cars passing by. ‘I was sitting, out of sight, above “the pub” with a large sound mixer in front of me organizing the sound. The jukebox could be switched on and off, but I decided whether it would actually play or not. Conversations at the door, where Wies Smals prevented latecomers from entering, were relayed loud and clear, live into the bar. A lot of noise, everyone waiting to see what happened, and then the audience would hear “no, no, you certainly can’t get in anymore”, although there really was enough room for more people and it hadn’t started yet, either. I only listened to what sounds got through to me. The visitors, who had been drinking more and more and still hadn’t seen anything, got increasingly annoyed. After hours of waiting almost everybody had left the bar, but for a small group of hardcore performance spectators. After hours of nothing I could be viewed, for a brief moment, in a long, narrow gallery above. I was covered in white make-up with thin raised eyebrows painted on. I just stood there, unmoving, looking at everyone, with questioning eyebrows. More and more people were brought in from outside and in the end the space was quite full. Then I left, without saying a word. People sniggered and made derisive remarks; they had been drinking quite a lot.’

The following day another group of visitors came to the same gallery, this time it was empty. Toebosch was wearing a dress which had been attached in a semicircle to the floor and the wall. She narrated her experiences of the previous evening, while knocking back two bottles of wine. Under her dress she had a small crackle organ, little bells and large cymbals, and on her dress a small contact microphone. ‘I watched how everyone entered; I sang and slurred my words with a local accent, getting pretty drunk. In fact it sounded awful, really ghastly. People were doubled up laughing. At some stage, I suddenly remembered my uncle’s unexpected death a few evenings before, at which I had by a remarkable coincidence been present. I started weeping bitterly, partly out of desperation about the situation I was actually in – I didn’t know how I could decently end it – and partly because of that traumatic experience. I couldn’t stop crying. Most people were highly embarrassed, and one by one, left the room. Beneath my blue dress, I was almost naked. Wies Smals came to me and patted my back saying “Moniek, hey Moniek” and click, the 60-minute video tape was full. That was also the end of Joyful Anticipation.’

Political Gestures

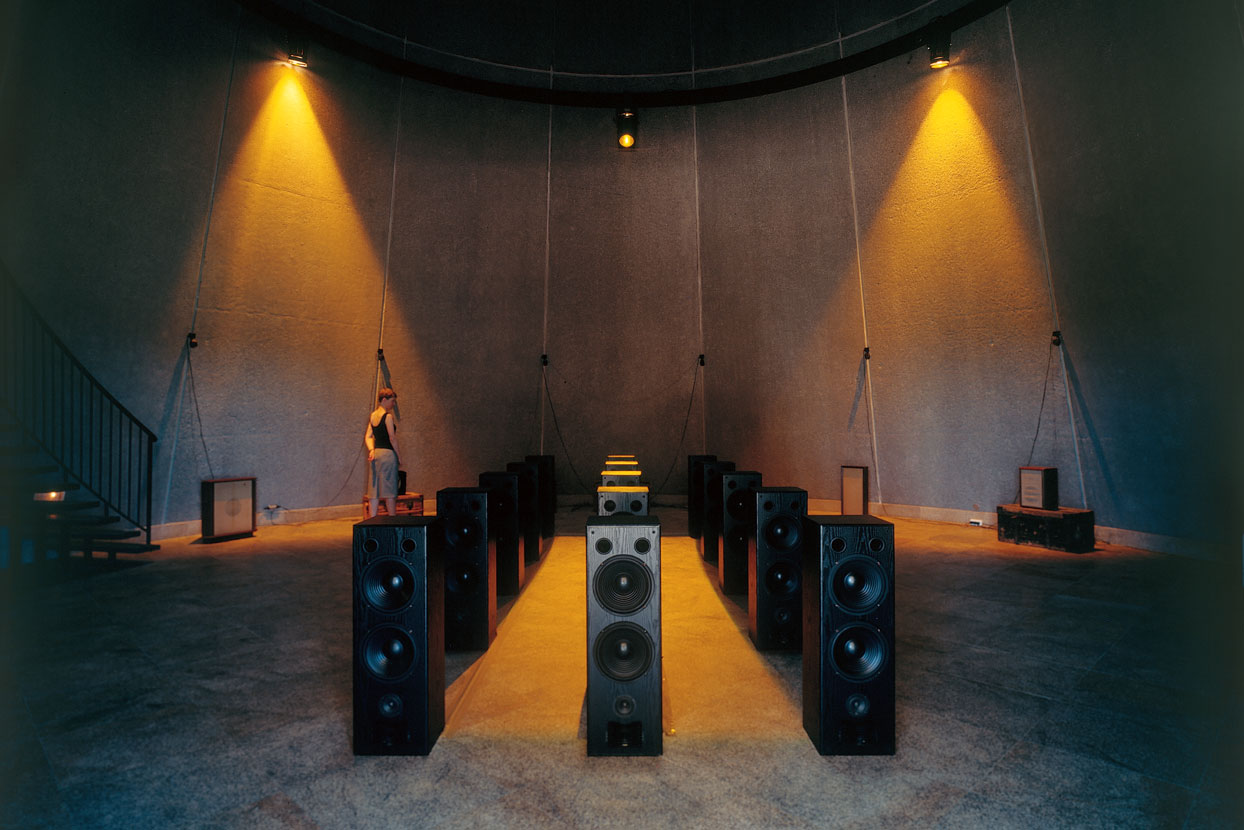

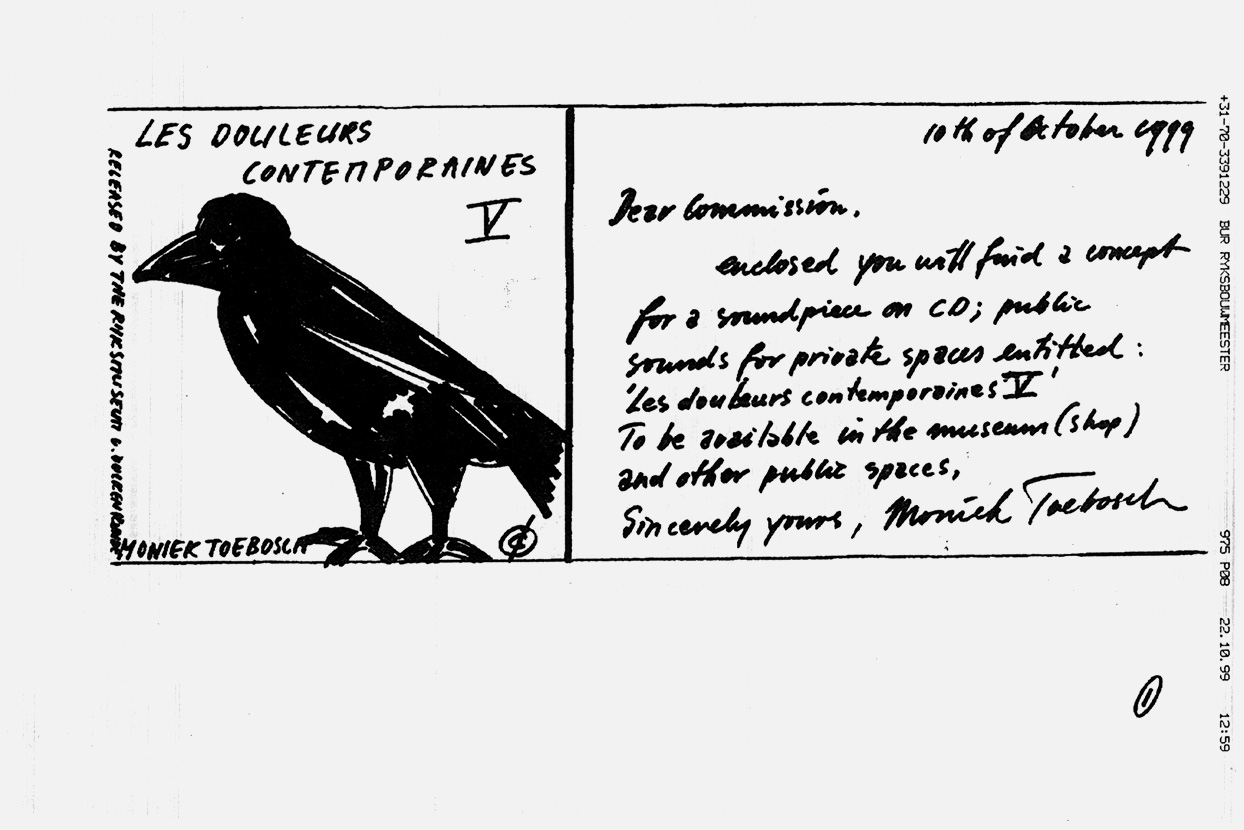

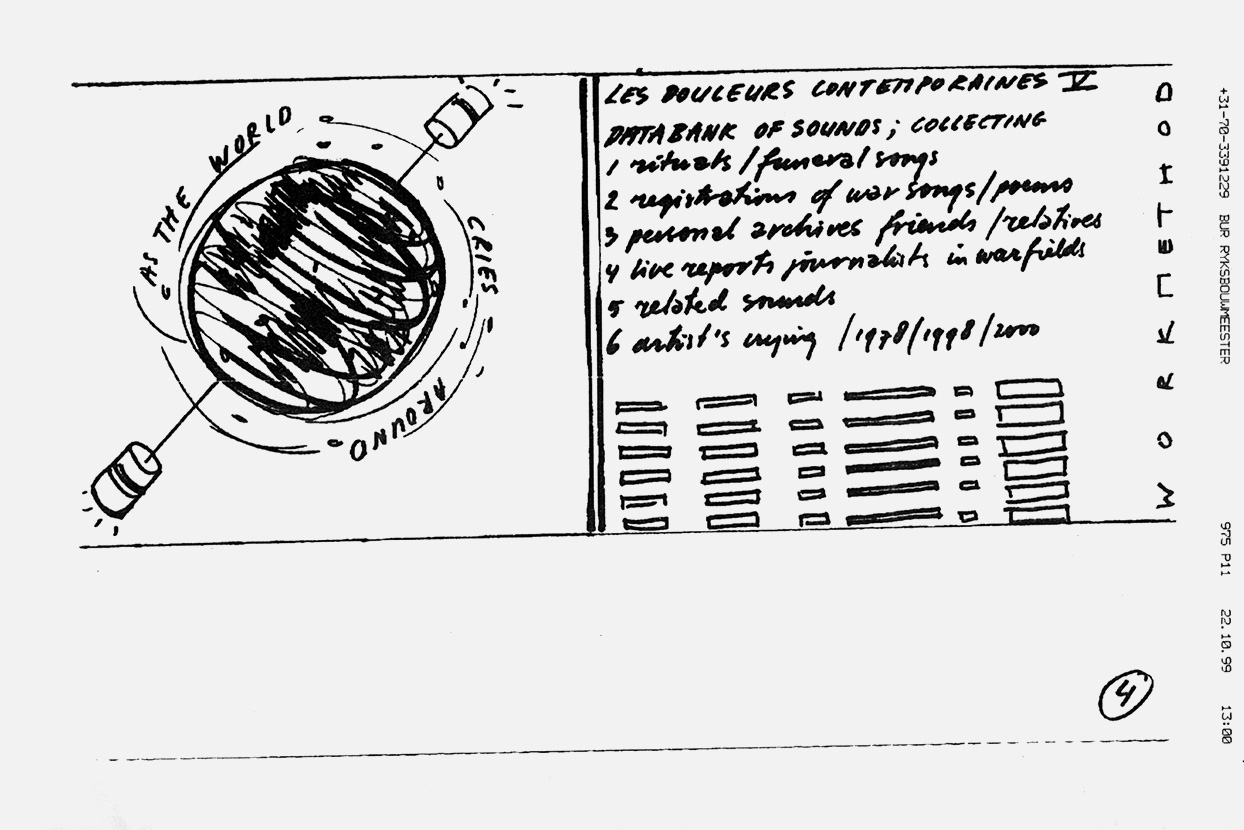

Toebosch’s activities continue to be varied, covering both the musical and the visual field, yet she does appear to be working in a more concentrated fashion. Between 1994 and 2001 she undertook a series of six works with the collective title Les Douleurs Contemporaines (Comtemporary Sorrows). She installed Les Douleurs IV in 1997 in Aldo Rossi’s conical tower in the park at Vassivière in France, part of the Centre National d’Art et du Paysage – a dramatically illuminated installation of loudspeakers, the sound of which was triggered by the visitors’ footsteps. The speakers in the outer circle simultaneously played a variety of melancholy music by people who had fled to France, like the Roma from Romania, the Greek composer Xenakis and the Algerian singer Cheb Khaled. Twelve speakers in two rows of six intermittently emitted the sound of marching soldiers that drowned the music. ‘At that time there were elections in France. At the art centre they weren’t entirely sure whether they would be able to continue if Chirac and his clique were to win. I wanted to make a political gesture. The tower was in fact an impossible exhibition space, all you could do there was work with music. The strange thing was that some people got quite upset as they walked through the installation. People in politics trying to keep culture in balance where it was being challenged.’

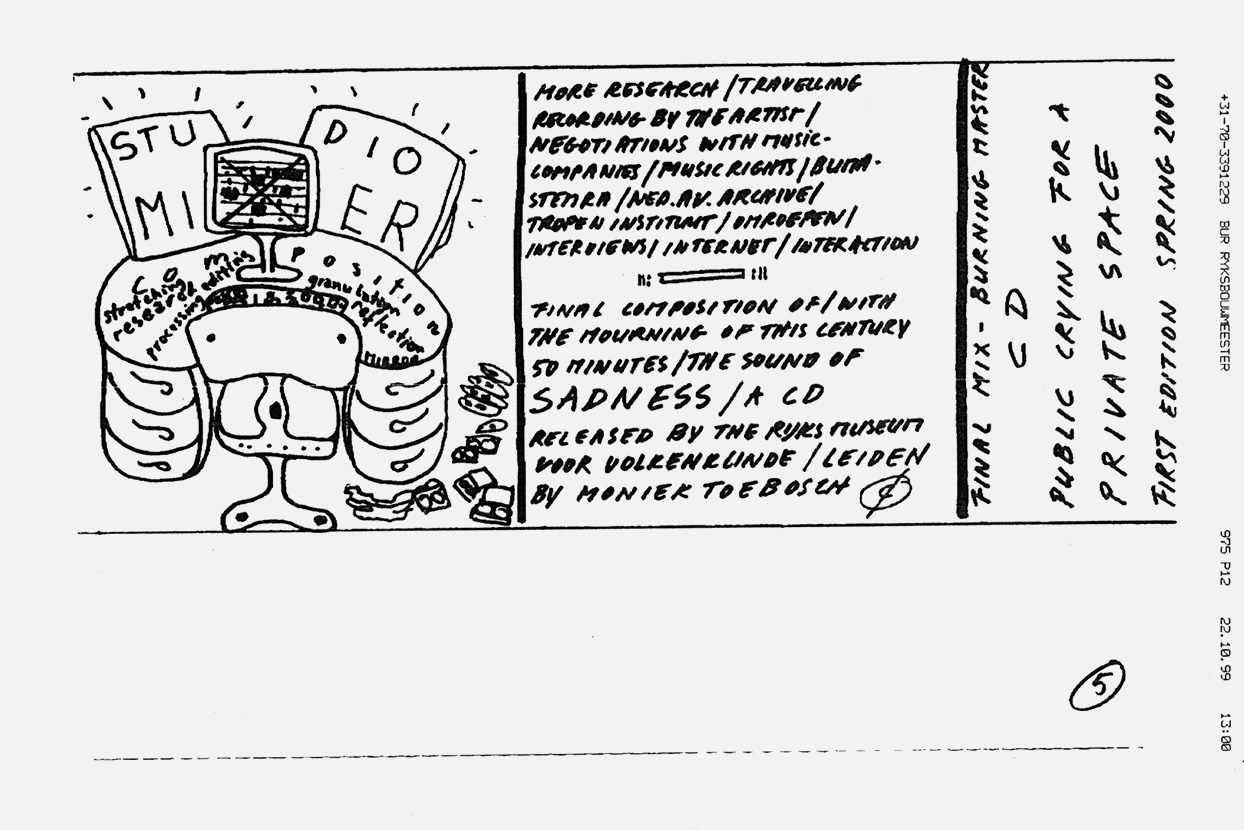

For a different version of Les Douleurs Contemporaines in Witte de With in Rotterdam, Fundacio Miró in Barcelona and Le Fresnoy in Tourcoing, Toebosch used weeping voices from radio, television and documentaries. Here again the visitor set off the lamentations himself, changing his position from spectator to perpetrator. ‘I got some of these sounds from the nos (Netherlands broadcasting association) archives. I also got fragments from a documentary by Johan van der Keuken in which a mother in Africa is holding a dead child in her arms. As I speak about it, I can clearly relive all those sounds. I have recordings by the film-maker Babeth van Loo, from her documentary on Haiti in which women are identifying their murdered husbands at a morgue. The women are weeping in a heart-rending way. But I also used the sound of weeping sports people, who just didn’t manage to win. That too is pain, quite a different kind of pain, but it was also included, because in our present-day society they are all equated. First you’re watching pictures of the war and then you have the soccer results dished up. So I included these sounds in the same funerary procession. The different sounds have not been named, I found that embarrassing. You might wonder whether you can just use them like that. In this case I thought I could, because it became a “monument of sorrow”. The weeping has been heard elsewhere as well.’

Toebosch’s last work to date, Les Douleurs VI (2000 / 2001), has been installed in the entrance and stairwell in the Museum of Ethnology in Leiden and can also be heard on cd. The formulation of the assignment for the eleven artists participating in the Percent for Art scheme (in which a percentage of the building cost is spent on art) was very time-consuming, because the identity of ethnology museums was under discussion. Toebosch formulated a number of questions herself. ‘I had made a sketch of a proposal, inept little drawings of people standing beside a statue wearing Indian and other headdresses. How do we see our culture? We only view things from our own standpoint. How do all those people with headscarves and beards look at the statue around the corner from where they live? How on earth should you interpret it without knowing the history?’ Toebosch visited the Ethnology Museum’s depot of some 60,000 musical instruments which are all lying motionless on the shelves. Each instrument is accompanied by a little card stating the region where it was found, but its makers are unknown. Almost all the instruments have been removed from somewhere, which also has highly negative and embarrassing associations. A few instruments are attributed to someone, but the rest are anonymous. The provenance of every important violin – when or by whom it was made – is known, but with almost anything from Africa, Indonesia, or wherever, the maker is unknown. I felt that I should pay tribute to the makers by allowing the products of their craftsmanship to play one more time.’ Toebosch made recordings of several instruments and made some digital adjustments, turning what had originally been a light bell into a heavy gong. In that way she transported sounds from past centuries and distant lands to the present time and space. She added to that the sounds of weeping from previous versions of Les Douleurs, putting them in a staccato rhythm and thus creating a kind of hip-hop.

Inspiring Developments

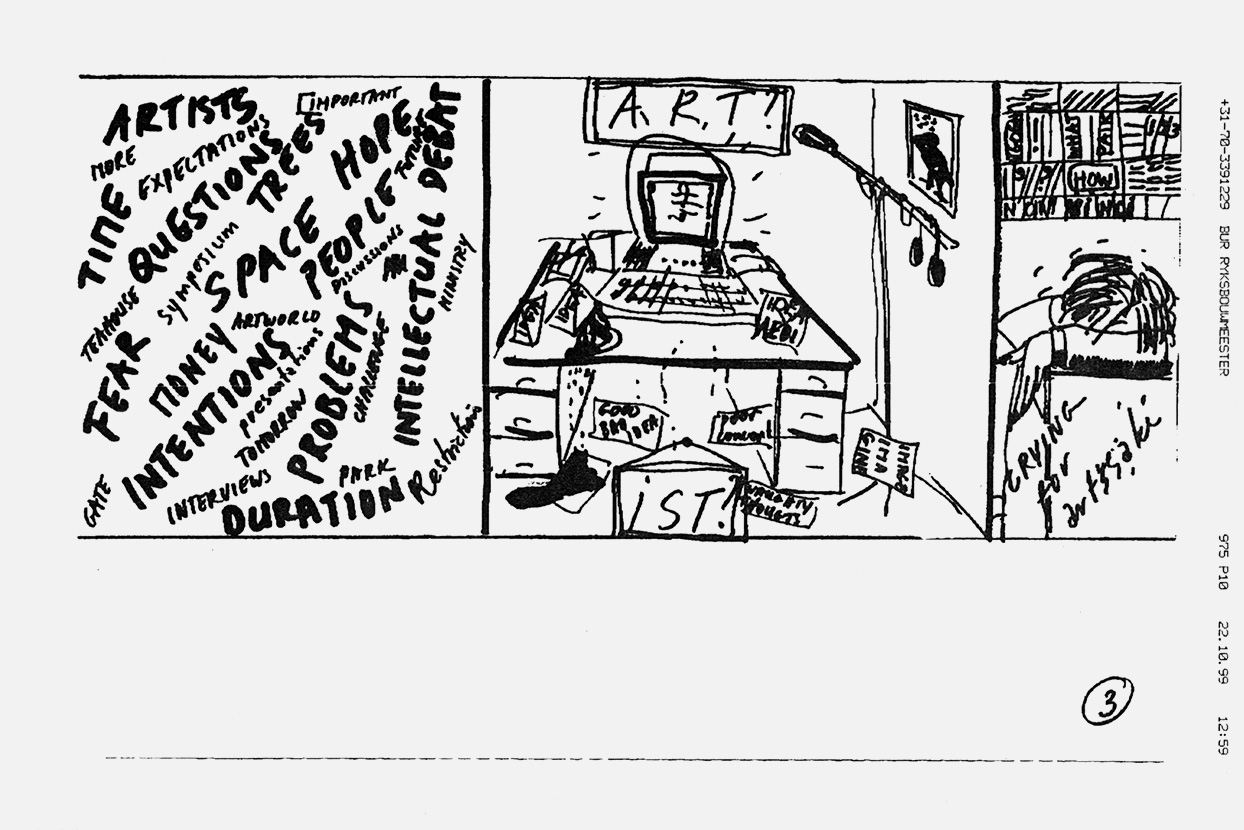

For some time now Moniek Toebosch has been the director of DasArts, a course for theatre-makers. Guest curators are called in to plan a thematic programme relating to the current political, social and artistic climate. All forms of the performing arts are addressed; the curriculum is flexible and broadly orientated. Toebosch is very much at home in this environment. She sees DasArts as a new work in which she plays the role of intermediary. ‘The composition of the group of participants is very important. For example participants from Lebanon and Israel who are not normally permitted to be in contact with one another, work together here. Highly confrontational, but encouraging. Also, participants from wealthy Western countries and less affluent countries provide mutual inspiration. Fresh initiatives concerning the performing arts ought to be set up to enable those involved to have a more active role on the home front in the future, along the lines of the Rijksacademie’s rain project, which supported young artists from developing countries wishing to embark on an artistic undertaking in their own country with technical resources, including contributions for the acquisition of equipment, building a website, etcetera. We should create an international network of academies, conservatoires and other institutions structurally providing cultural development aid for their former students.’

Toebosch is surprised that there is once again considerable interest in performances, not only from the visual arts side but also from the theatre. The emphasis now is more on movement and rituals, owing, according to Toebosch, to a need for a commentary on the ‘loss’ of traditional religions and the growing interest in all forms of meditation. But there is also the hard-core theatre-maker / performer who has a critical attitude towards society and the arts themselves, and translates that into harsh images.

She sees DJ Spooky, the Wax Wankers and other musicians as continuations of her performances with Waisvisz. ‘They quote equally insolently from all manner of disciplines – jazz, classical, pop – and freely use computers and other machines to make music, live on stage. DJ Kypski and the Wax Wankers, for instance, combine high and low art intelligently. They use music by Charles Ives and scratch with it. A sound artist and DJ like Mo Becha also quotes work by composers of electronic music to make his own work. He is a perfect DJ of modern, contemporary music. And at steim they infrequently present a new generation of musicians on Thursdays. I recently attended a performance by Ton Verbruggen (also known as TokTek), who not only scratched but also drove his computer with a joystick, fabulous. It was hard to sit still, it was so exciting, very concentrated, brilliant.’

Toebosch also notes interesting developments in the perception of sounds. Specific venues are created where music can be listened to, like lounges, festivals and other temporary locations. The listener has become nomadic, he wants to listen to the same music under different circumstances, with a different audience. The methods of processing sound using the computer have also become far more accessible, the present generation can programme and edit themselves. ‘The new generation of sound artists and musicians is so much better geared to perceiving and experiencing different things simultaneously. They are far better at analysing complexity. I get totally confused, pay equal attention to everything. They look more at the overall picture and are better able to select. They “multi-task” from an early age. I’m especially aware of that now that I’m working at DasArts and have a fulltime job. I think in the future I shall aim for emptiness, for even less and lighter. When all is said and done, you need to do very little to create an impressive work.

Brigitte van der Sande is an art historian, independent curator and advisor in the Netherlands. In the nineties Van der Sande started a continuing research into the representation of war in art, resulting in exhibitions like Soft Target. War as a Daily, First-Hand Reality in 2005 as BAK, basis voor actuele kunst in Utrecht and War Zone Amsterdam (2007–2009), as well as many lectures, workshops and essays on the subject within the Netherlands and abroad. In 2013–2014 she curated See You in The Hague at Stroom Den Haag, and co-curated The Last Image, an online archive on the role of informal media on the public image of death for Funeral Museum Tot Zover in Amsterdam. Van der Sande is currently working on a concept for a festival of non-western science fiction, that will take place in 2016.