Seven Work Ballets and Mierle Laderman Ukeles

July 13, 2017review,

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Seven Work Ballets, Kari Conte, ed., Kunstverein Amsterdam, Grazer Kunstverein, Sternberg, 2015, ISBN 9783943365931, 232 pages and Patricia C. Phillips with Tom Finkelpearl, Larissa Harris and Lucy R. Lippard, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Queens Museum, DelMonico Books, Prestel, 2016, ISBN 9783791355382, 256 pages

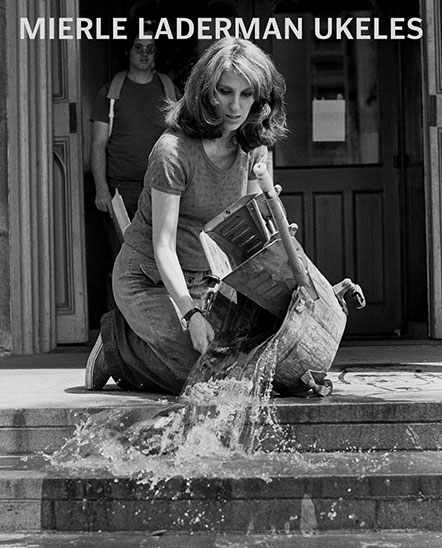

Almost fifty years ago, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles coined the concept ‘maintenance art’ in her ‘Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Proposal for an Exhibition “CARE”’ (1969). Central to maintenance art is ‘Life Instinct’, what she describes as: ‘the unification; the eternal return; the perpetuation and MAINTENANCE of the species.’ We learn from the same manifesto that the exhibition of maintenance art would ‘zero in on pure maintenance, exhibit it as contemporary art, and yield, by utter opposition, clarity of issues’. She has dedicated her practice to fulfilling this goal, clarifying through opposition, namely, the neglect of reproductive labour under capitalism.

Through writing, making and forging alliances with the press she makes both her work and the issues it advocates visible. Yet in-depth publications about her work have been largely non-existent, until now. One reason is the challenge posed by any book-length presentation on this artist – never mind an exhibition – given the abundance of her carefully executed interpersonal communications. In preparing an exhibition of her work, Queens Museum curator Larissa Harris asked: ‘How can that [the web of interaction, negotiation, personal alliances, and persistence] be made visible here?’ She answered her own question with: ‘It will come in the making of the show.’

Harris echoes what I have learned of Laderman Ukeles’ ambitious projects in these two publications: carefully lay a path, but make space for surprise, the aesthetic factor at the moment of realization. So while Harris included many archival documents on the social relations among municipal departments, workers and arts institutions that gave way to the artist’s work, fuller explanation necessarily relied on the catalogue.

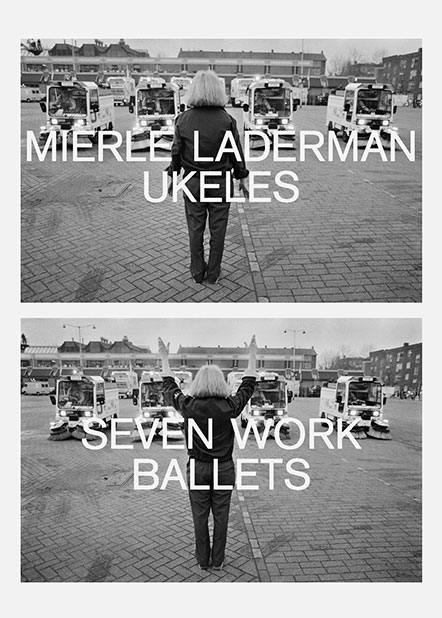

The spark of risk, possibility of failure and joy at the moment of completion are pivotal to Laderman Ukeles’ process in Seven Work Ballets. The works of the same name consisted of ambitious public performances on maintenance, made in collaboration with sanitation departments from New York to Rotterdam to Givors to Echigo-Tsumari between 1983 and 2012. These works saw her choreograph heavy machinery in collaboration with workers in an effort to invigorate and secure community pride. Editor Kari Conte sets the personal tone at the outset of the book, focusing on the lasting impression left on her as a young cultural worker after meeting Laderman Ukeles at Fresh Kills. What follows is a detailed explanation of the work accompanied by intimate testimonials from the artist. The reader is continually pulled back into the original moment of making through the artist’s words. In a fluent and conversational tone, Laderman Ukeles describes the motivations behind her ballets, always through careful observation, often noting a lack or misrecognition about maintenance work on the part of the public or city. She also details how she went about making allies and her strategies in speaking with collaborators, giving the reader a sense of her ability to turn initially resistant collaborators into active participants with decisive ownership over the form of the ballets.

Similarly, the stunning images (black and white as well as colour) of the seven-part ballet and documents produced in its preparation further animate the reading experience. These snapshots of Laderman Ukeles’ tour de force are necessarily embedded in language – the ekphrastic script in her testimonials includes terms she coined with her collaborators (‘The Sea Lions Hunt the Herrings’, ‘The Kiss’), and also the personal thank you notes so integral to her works and their public moments. An exhaustive ‘Credits and Details’ section closes each chapter, hammering in the magnitude of the labour (manual, machinic, institutional and affective) behind each production.

The ballet book is a precise complement to the Queens Museum catalogue, which delves less into the choreographies and evidently has an institutional, even political purpose. As in the case of, for instance, Patricia C. Phillips’ essay ‘Making Necessity Art’, which attends to the entire span of Laderman Ukeles’ career. Phillips looks at unrealized projects and their impact on the artist’s realized work, and links Laderman Ukeles’ projects to the then burgeoning field of social practice now par for the course in art academies and the art world at large. Phillips makes an important point: this is a uniquely consistent and influential practice at once engaging with hegemonic systems, labour, and, specifically, women’s labour head-on.

Yet the rather conventional and glossy design of the book, the amount of colour photos and redundant explanatory labels for each mentioned work, indicate a desire to insert Laderman Ukeles – as an archive – into a more general art historical narrative. The back-of-book redeems this tendency by once more ingraining the personal in the reader, offering us a treasure trove of the artist’s writings, if somewhat out of place amid its coffee-table presentation.

Lucy R. Lippard gives a personal account of Laderman Ukeles as a mother and artist – not as a set ‘mother and artist’ category, but as a the embodiment of a living context for the production of art and artistic thinking: ‘It was two moms in the playground chatting about art that would shake up the art world for decades to come.’ It comes as no surprise then, that the artist’s earliest work concerned that of mothering.

Seven Ballets and Mierle Laderman Ukeles invest in photography and documentation of process to preserve the ephemeral. At the same time each tome struggles with how to include the artist’s collaborators. For if the artist’s motto has been to make maintenance visible, the books must pay tribute to the work of sanitation workers. The catalogue makes a deliberate choice to do so: former Queens Museum director and current New York cultural commissioner Tom Finkelpearl interviews New York commissioners of sanitation who worked with Laderman Ukeles, providing an institutional ‘view from the other side’. In aggregate, the interviews bring to the fore the complex interactions involved between a large city bureaucracy and an artist in residence. Seven Ballets (partially steered by Laderman Ukeles) opts for a narrative, quote- and credit-heavy approach to expand on the wider ecosystem (human and non-human) the ballets reflect on and affect.

However complicated the task of presenting an artist’s work, especially that of one who teeters on the edge of civic initiative, each of these books fills a lack: one in artistic process, the other in art history. Both insist on the relevance of Laderman Ukeles’ work in an era of disintegrating public funding and unabashed instrumentalization of workers’ needs. I couldn’t agree more on the relevance of a practice that attends to community and its respect. If I have one gripe, it would be a longing to have heard somewhere within these pages from contemporary art practitioners – instead of art historians or curators – whose work wouldn’t have come to pass without Laderman Ukeles. The aesthetic joy in making and experiencing art is after all what has made Laderman Ukeles persist and thrive.

Sarah Demeuse (US / Belgium) makes exhibitions and writes. She often works collaboratively as Rivet. She is the instigator behind dos, a forthcoming podcast series. Sarah also teaches in the Curatorial Practice MA programme at School of Visual Arts in New York.