Sixty-five Situations

September 30, 2004artist contribution,

What's the ‘Archive’? You Say That for Foucault the Archive Is ‘Audiovisual’?

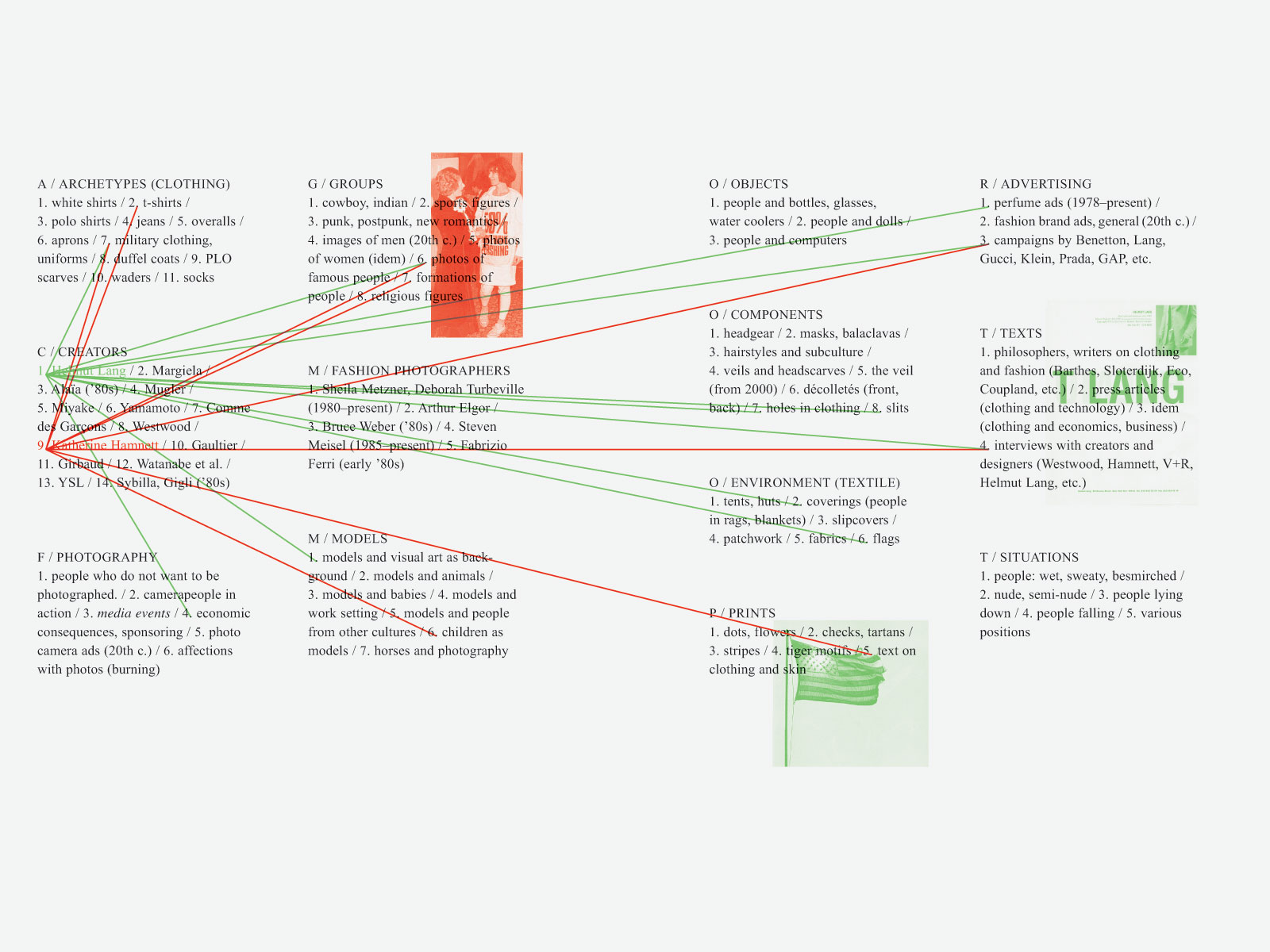

Why speak in terms of ‘archive’? We use the concept of ‘archive’ these days to come to come to grips with the rapid proliferation of images. Archive is a key word, like the words ‘postmodern’ and ‘digital’. It implies the processing of actions and ways of thinking, a way of imposing some order and of generating a consciousness that deals with ‘production’ in a different way, that manages to slow it down. You do not start an archive. Only in the course of time does it become clear that you are assembling one. First (1977) you collect images in order to create a ‘counterlanguage’ – a series of images and texts intended to supply the over-exploited concept of ‘fashion’ with different arguments. You want to show that an infinite quantity of language and knowledge has developed concerning the body, concerning clothing. What you find lacking in fashion books and magazines is precisely what you start collecting. When does a collection become an archive? You create a precedent with the selection of a single picture: you need more in order to demonstrate differences or similarities. Contexts, names, notes, selections. Dates suddenly become important. Gradually the folder with the collection of images is transferred to a box, which starts to look like an archive box. It is not a question of quantity or completeness. It is more that the material leads you to speak. The images you collect lead to conversations, discussions. It is not important to collect everything on a certain subject. That you make you a bookkeeper. Only the images that interest you may go into the archive.1 Sometimes you refuse an image. You collect only what intrigues you, what stands at the juncture of a position, at the breaking point of traditions, on the cutting edge of the period and at a specific moment, identified by you.

Examples of turning points

1. Katherine Hamnett ushers in a new era to follow the punk period, in which designers become associated with business and at the same time do not shy away from engagement. The photograph from my archive shows Hamnett being received by Margaret Thatcher. With a great sense of publicity she wears a T-shirt under her coat bearing the slogan ‘58% Don’t Want Pershing’. There could be no better conjunction of clothing, body and message.

From the folders: ‹Text on clothing and skin›, ‹British designers after 1980›.

2. In the early 1990s Helmut Lang associated his archetypal, modern clothes with publicity campaigns that systematically challenged the management of photography. Like Benetton and Comme des Garçons he uses photographs from Robert Mapplethorpe’s archive in his ads. The photo is displayed like a ‘postage stamp’, flanked by a painstaking colophon. In doing so in reintroduces Mapplethorpe’s work in the media as well as in the campaign running in parallel with his clothing collection. The controversy attached to Mapplethorpe’s work in the United States fades because of this uncensored advertising version, distributed without hindrance under Lang’s label.

From the folders: ‹Helmut Lang›, ‹Photography›, ‹Advertising›, ‹Models and visual art as background›, ‹Military clothing›.

What’s the ‘archive’? You say that for Foucault the archive is ‘audiovisual’?

Archeology, genealogy, is also a geology. Archeology doesn’t have to dig into the past, there’s an archeology of the present – in a way it’s always working in the present. Archeology is to do with archives, and an archive has two aspects; it’s audiovisual. A language lesson and an object lesson.

It’s not a matter of words and things. We have to take things and find visibilities in them. And what is visible at a given period corresponds to its system of lighting and the scintillations, mirrorings, flashes produced by the contact of light and things. We have to break open words or sentences, too, and find what’s uttered in them. And what can be uttered at a given period corresponds to its system of language and the inherent variations it’s constantly undergoing, jumping from one homogeneous scheme to another. Foucault’s key historical principle is that any historical formation says all it can say and sees all it can see.

―From ‘Life as a Work of Art’, Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations 1972–1990, p. 96 Columbia University Press, New York, 1995. (originally from Pourparlers, 1990) interview with Didier Eribon, Le Nouvel Observateur, 23 August 1986.

1. Institutes can gather all information and data on a certain subject. In doing so they create volume, quantity, power and ostensible objectivity. An individual can later uncover something specific within and make new cross-connections.

Joke Robaard is a visual artist.