Social Enclaves and Art Tolerance Zones

November 1, 2005review,

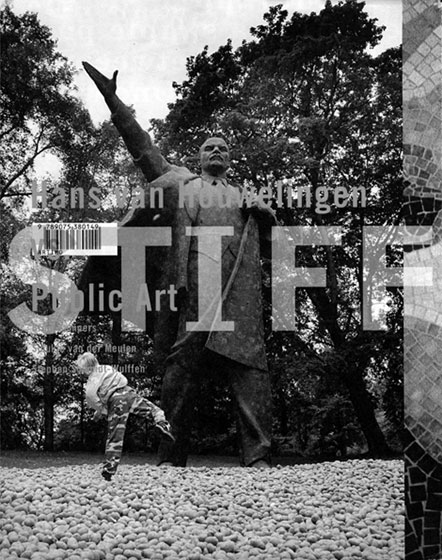

STIFF, Hans van Houwelingen vs. Public Art, Artimo, Amsterdam 2005, ISBN 9075380143

I always used to think that a discussion about the work of Hans van Houwelingen would be easy. All you’d need to do would be just look, exchange ideas and proceed to the order of the day. Once you leaf through STIFF however, a massive tome about Van Houwelingen versus Public Art, this idea ceases to be tenable. His images, structures, texts and conceptual adventures are viewed, nosed through and assessed in essays by Bram Kempers, Sjoukje van der Meulen and Stephan Schmidt-Wulffen, with extensive glosses by Van Houwelingen himself. Van Houwelingen in public space, Van Houwelingen and the ‘counter-monument’, Van Houwelingen with his divergent identities. Van Houwelingen is an artistic glutton. ‘People like you are rare’, Her Majesty declared, and it’s true that this artist who has enjoyed royal patronage while being at the same time an unmistakeably political artist is the Picasso of the polder, or consensus, model. That’s the case at least if we are to believe art sociologist Kempers, who defines current commissioned art as a model of consultation ‘based on the creation of social enclaves that often provide a tolerance zone for controversial art’. Van Houwelingen makes ‘artworks that can set people thinking without undermining the guaranteed security of the polder model’. This is art for the reservation, images for a village in the polder – literally and figuratively. Kempers therefore has plenty of reservations about Van Houwelingen’s artistic activities, and their futility is exposed in elegant terms.

The work of Van Houwelingen in the public domain consists of proposals for art works or interventions. By no means all the proposals have been implemented, but they invariably cause controversy and discussion. By stringing banalities together STIFF attempts to persuade the reader that what is involved here is an exceptional oeuvre. But it does so in vain because the crucial question of its artistic quality is hardly posed. This quality is presented as self-evident. STIFF then is also above all a manual about how to sell this marvellous art in the public domain to ‘various sorts of consumer and patron’ and to ‘all kinds of intermediaries: consultants, politicians, civil servants, critics and scholars’. And STIFF does this in a way that confirms all my prejudices. After reading Camiel van Winkel’s Moderne Leegte. Over kunst en openbaarheid of 1999 I still wasn’t out of the morass either – the style and mode of expression are so classy that the emptiness of failed art in the public domain still acquires an artistic aura. STIFF is more innocent and thus more revealing, because form and content cover for each other very precisely here. The photos of abandoned sculptures lost somewhere in a square, in public gardens, on a plinth, just left behind in the cold, and the commentaries on them leave little room for doubt. Art in the public domain really is poverty-stricken and a sorry spectacle – it literally stinks. Stupid politicians, narrow-minded civil servants, blind critics and of course the loveless bureaucracy are responsible for this. But so are those who speak up for the welfare of the kangaroos that Van Houwelingen in one of his proposals wants to keep in the grounds of a children’s hospital. According to Kempers, they are concerned ‘not with arguments – either artistic or veterinary – but with a publicity success, that they would have much more difficulty getting in other instances’.

Kempers speculates endlessly in what is the laziest, most cowardly and lame text about art I have read in years. For Kempers art has nothing to do with divine inspiration, talent, or knowledge – no, for him it is a matter of ‘forming an unbeatable coalition with other parties’. Somewhere he says that Van Houwelingen ‘receives and passes on contemporary and historical signals like a dish antenna’ – and, it’s true, there he is on his way to a municipal district council in The Hague, with the question of whether ‘there is room for a satellite tolerance zone’. Here and elsewhere it appears that Kempers and Van Houwelingen genuinely haven’t a clue that good art comes about in ways that are unexpected, and not via well-worn paths. That good art can be modest and invisible, that it is not pushy, does not provoke any controversy or result in any exchange of abuse, but that in its essence it operates invisibly. That good art never progresses with the aid of functionaries, mediators and other busybodies but makes its way with the aid of the heart and the intellect, to use the language of a rickety and banal dualism.

In STIFF the whole artistic world is a reservation, in which partners plan a deal. But my problem is whether Van Houwelingen, the ultimate ‘poldering’ artist after Pim Fortuyn’s revolution dealt the polder model its death blow, isn’t really passé as an artist. It is all very well in multicultural Holland for Van Houwelingen to worry about kangaroos, asylum seekers, a Moroccan artist or about Pedro Cossa in Mozambique, but he is also a white artist who set Piet Esser’s lonesome statue of the engineer Cornelis Lely on a Roman-style obelisk. Or a modern neoliberal who breathed new life into a discarded Stalinist statue of Lenin. And of course, beyond Kempers’ art tolerance zones, he is someone who, in the guise of a lonesome tourist in Japan, plays the mirror image of the Japanese tourist in the Keukenhof, in a series of manipulated photos entitled Visiting Japan. Far from the polder, without any compass to guide him and abandoned to his fate, he ends up in Hiroshima. There he mingles with the victims of the American atomic bomb running in total panic with their burns. Without any sense of proportion, of distance, any form of reflection, of silence and contemplation Van Houwelingen has inscribed himself in a real piece of ‘history’, sixty years on and with the aid of a computer and some old photographs.

Any artistic criticism here is quite beside the point.

Fortunately Sjoukje van der Meulen in her essay on holocaust monuments and counter-monuments does not have to describe this painful episode as her text was written before Van Houwelingen visted Japan. Her restrained style is a relief – all at once you find yourself thinking about a real theme. And luckily she knows where it all started in art and she can even lend Van Houwelingen’s work some weight. Her remarks about the nineteenth-century ornament of the statue of Willem Alexander, the critical content of the Lenin sculpture, and above all her oblique question about the Eusebiuskerk suddenly gives this book, that is stiff to the point of rigidity, some actual backbone. Are the lamps of the Marktplein in Arnhem, focussed on the Eusebiuskerk, a critical metaphor, ‘or do they recall in an openly monumental gesture, the searchlights that tried in vain to capture the bombers in their beams, so they could be shot down before destroying the church?’

Finally an idea that is as simple as it is clear, that really stands out in the midst of the certainties of the manifestoes, offers and counter-proposals published here.

Paul Groot (the Netherlands) is editor of the periodical Mediamatic and a filmmaker. His most recent project was the film Daisukes Tokyo-ga.