Soft Urbanism

Neighbours Network City (NNC) in the Ruhr Region

November 1, 2006essay,

Elizabeth Sikiaridi and Frans Vogelaar of invoffice for architecture, urbanism and design in Amsterdam are investigating the interaction between the physical and the digital public domain in contemporary urban networks. They are interested in the way that the built environment relates to the space of mass media and communication networks and how these influence each other. On the basis of the project Neighbours Network City for the city of Essen in the Ruhr region, they reveal how this design research is taking shape.

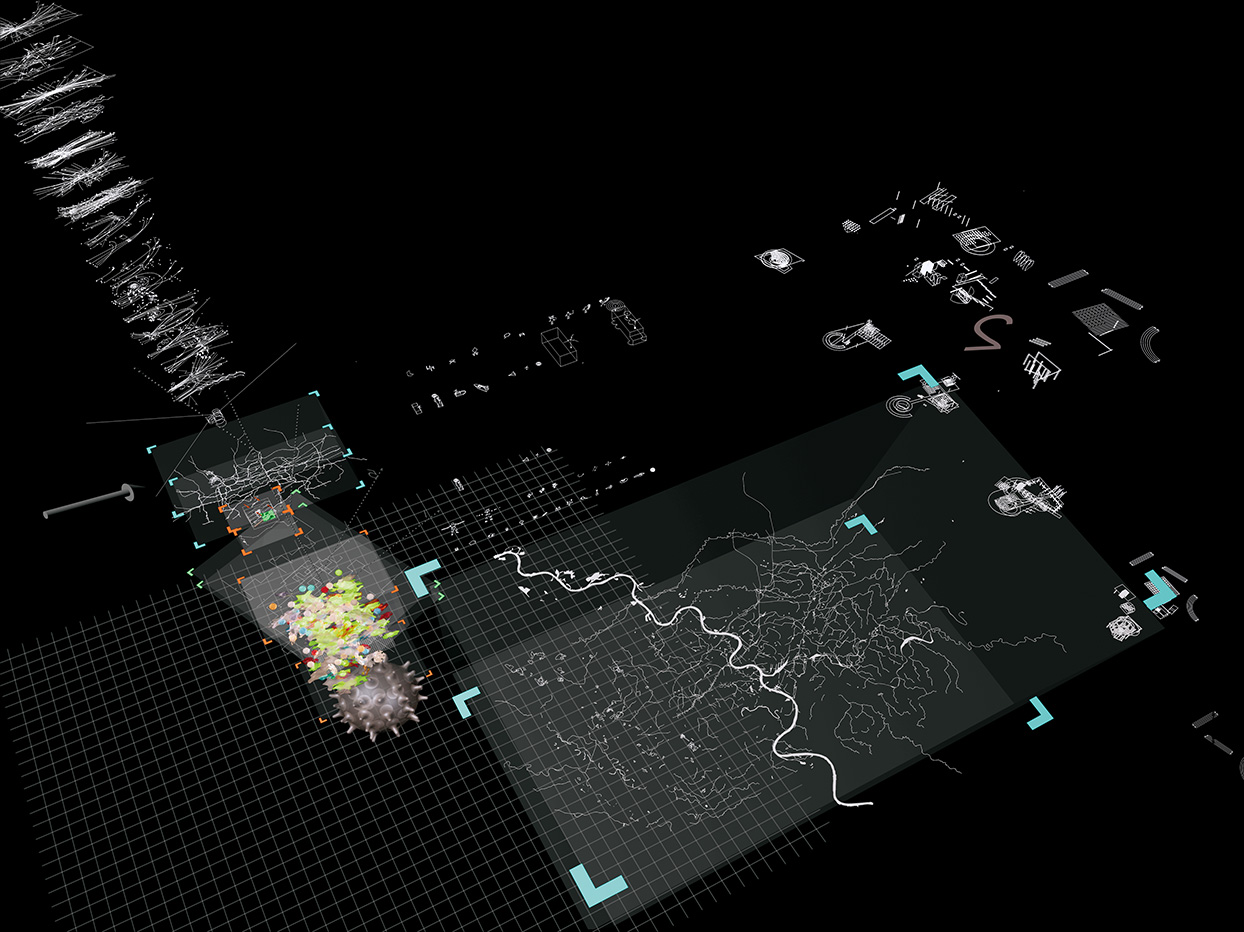

Situated in the west of Germany not far from the Dutch border, the Ruhr region is part of the West-European urban network. The urban structures of the Ruhr echo the industrial networks that shaped this cityscape: the hidden patterns of the underground mining galleries and the logistical systems of waterways, railways and roads that cut through the urban landscape. In pre-industrial times, this region was so sparsely populated that it was unaffected by the urban forces that led to the emergence of the historical compact city in other parts of Europe. Unlike the traditional European city, the Ruhr developed from the beginning of the nineteenth century, with the rise of industrialization, until the middle of the twentieth century, expanding into an urban network on a regional scale. In the post-industrial era, with the closure of the mines and the demise of heavy industry, this urbanized landscape became more and more fragmented as manufacturing sites were abandoned and city populations steadily dwindled. As a result, the cityscape of the Ruhr is today characterized by fragmentation and gaps in the urbanized suburban peripheries.

In order to understand the highly complex patterns in this cityscape, it needs to be read as a network of overlapping and interweaving traffic arteries, waterways and media connections. To get to grips with this dynamic urban fabric, to comprehend the forces at work within it, one has to appreciate the relations inherent in this fragmented networked landscape. It is a question of understanding the systems that give this splintered landscape its complex – and dynamic – open structure.

Communication Model / Circuitry

It is essential that we comprehend this networked cityscape as part of our contemporary urban condition. In the words of Vilém Flusser (1920–1991), philosopher of communication: ‘In order to understand such a city at all, one must give up geographical notions and categories in favour of topological concepts, an undertaking which is not to be underestimated. One should not think of the city as a geographically determined object (like a hill near a river, for example), but as a bend, twist or a curvature in the intersubjective field of relations.’1 According to Flusser, this ‘topological thinking’, thinking in (spatial) relations and not in geometries, implies that ‘the architect no longer designs objects, but relationships... Instead of thinking geometrically, the architect must design networks of equations.’2

In Flusser’s (ontological) vision, the new city would be ‘a place in which “we” reciprocally identify ourselves as “I” and “you”, a place in which “identity” and “difference” define each other. That is not only a question of distribution, but also of circuitry. Such a city presupposes an optimal distribution of interpersonal relationships in which “others” become fellow human beings, “neighbours”. It also presupposes multi-directional traffic through the cable of interpersonal relationships, not one-way as in the case of television transmissions, but responsive as in the telephone network. These are technical questions, which have to be resolved by urbanists and architects.’3

Flusser describes the city in terms of this communicative model: ‘Geographically, the city will therefore take in the entire globe, but topologically, it will remain, for the time being, a barely noticeable curvature in the wider field of human relations. The majority of interpersonal relationships will lie outside it (in contemporary civilisations).’4 Hence, the plexus of interpersonal relationships lies in other communication systems outside the urban setting, such as the media networks. The physical cityscape is therefore only a particular instance of communication space. It has to be developed by an integrative approach, which addresses both urban and media spaces of social interaction. Placing the issue in a general model of communication, as Flusser does, allows the urban discourse to be shifted from the morphological level of a formal (‘geographical’) description of the fragmented cityscape to a ‘topological’ understanding of the relations and networks that pervade it. Here the term ‘urban’ describes an overlapping and superimposing of communication spaces and networks, a superimposing of interpersonal relationships and dialogue.

Hybrid Space / Soft Urbanism

Today, media networks (Internet, telephone, television) are influencing and interacting with ‘real’ places. The emerging space of digital information-communication flows is modifying not only our physical environment but the social, economic and cultural organization of our societies in general. Examples of this hybrid space can be found everywhere in our daily lives. Take, for instance, the private (communication) space of mobile telephony, creating islands of private space within public urban space. Or monitored environments where cameras keep watch over open urban areas. More examples can be found in our private environments, as our homes become ‘smart’ and our cars become networked spaces with, among other thingss, GPS navigation. Physical space and objects should not therefore be looked at in isolation. Instead, they should be considered in the context of and in relation to the networked systems to which they belong and with which they interact. These hybrid, ambivalent spaces are simultaneously analogue and digital, virtual and material, local and global, tactile and abstract.

The relationship between the physical and digital public domain is becoming more and more of a design challenge for architects and urban designers who are assigned the job of defining and realizing space for social interaction. They have to explore how the ‘soft’ city relates to and interconnects with its finite material counterpart, the living environment. They have to develop interfaces between the ‘virtual’ and the material (urban) world and devise hybrid (analogue-digital) communicational spaces. The new interdisciplinary field of Soft Urbanism researches these transformations in the architectural-urban space of the emerging ‘information-communication age’ and explores the dynamic interaction between urbanism and the space of mass media and communication networks. Soft Urbanism deals with information-communication processes in public space, the soft aspects overlying and modifying the urban sprawl: the invisible networks that act as attractors, transforming the traditional urban structure, interweaving, ripping open and cutting through the urban tissue, demanding interfaces.

Soft Urbanism is not therefore about determining places, but about creating frameworks for processes of self-organization. Soft Urbanism not only intervenes in the realm of infrastructure, it adopts its concept and follows its paradigm. It represents an inherently flexible approach by expanding the possibilities of social interaction and opening new paths of urban development. invoffice first formulated these themes when working on the Public Media Urban Interfaces project.5

The theme was further developed during a series of projects geared to developing ‘soft urbanism’ strategies which can steer and support the ongoing growth, transformation and recycling processes in the urban landscape. Such strategic intervention is achieved by exploiting the forces at work in the urban networks.

Neighbours Network City

The Neighbours Network City, a project developed by invoffice in 2004 for the city of Essen and the Ruhr region in Germany as the Cultural Capital of Europe 2010, is based on and addresses the networked structure of the Ruhr Valley. The nnc project operates on the scale of the agglomeration comprising 4, 435km 2 and over 5 million inhabitants; for, in 2010, the Cultural Capital of Europe will not be a city but a region: the Ruhr Valley.

The nnc proposes an infrastructure that can be decentrally deployed and is open for bottom-up development. This infrastructure will help to create openings to initiate and support urban cultural self-organizational processes. As the inverse of cnn, the nnc project develops synergies in the many local forces in the urban network to create an open Gesamtkunstwerk, the Cultural Capital Ruhr.

The goal of the nnc is to strengthen the public space of the network city of the Ruhr, which is in danger of steadily disintegrating into socially and ethnically segregated areas. Nowadays, when addressing public space, one has to consider not only urban public space, but the media public space as well. In fact, the traditional functions of public urban space are being taken over by telecommunication networks, where topical issues are disseminated and discussed and merchandise is showcased and sold. Whereas, in the past, the settings for recreation and festivities were provided by public space, they are now being increasingly provided by radio, tv, telephone or Internet. The nnc focuses on both media and urban public space, creating interfaces between the physical space of the city and the spaces of media communication. It activates both urban and media public space and develops scenarios to reinforce the public space of the fragmented urban landscape of the Ruhr. A true inverse of cnn , it uses the potential of communication technology to embed the global media space in the local public space of the city.

The nnc proposal consists of a series of interconnected subprojects, each of which addresses a different layer of the urban network and thus follows a different ‘network logic’. However, these subprojects are also interwoven, in the sense that they activate and strengthen the ‘knitted networks’ of the cityscape.

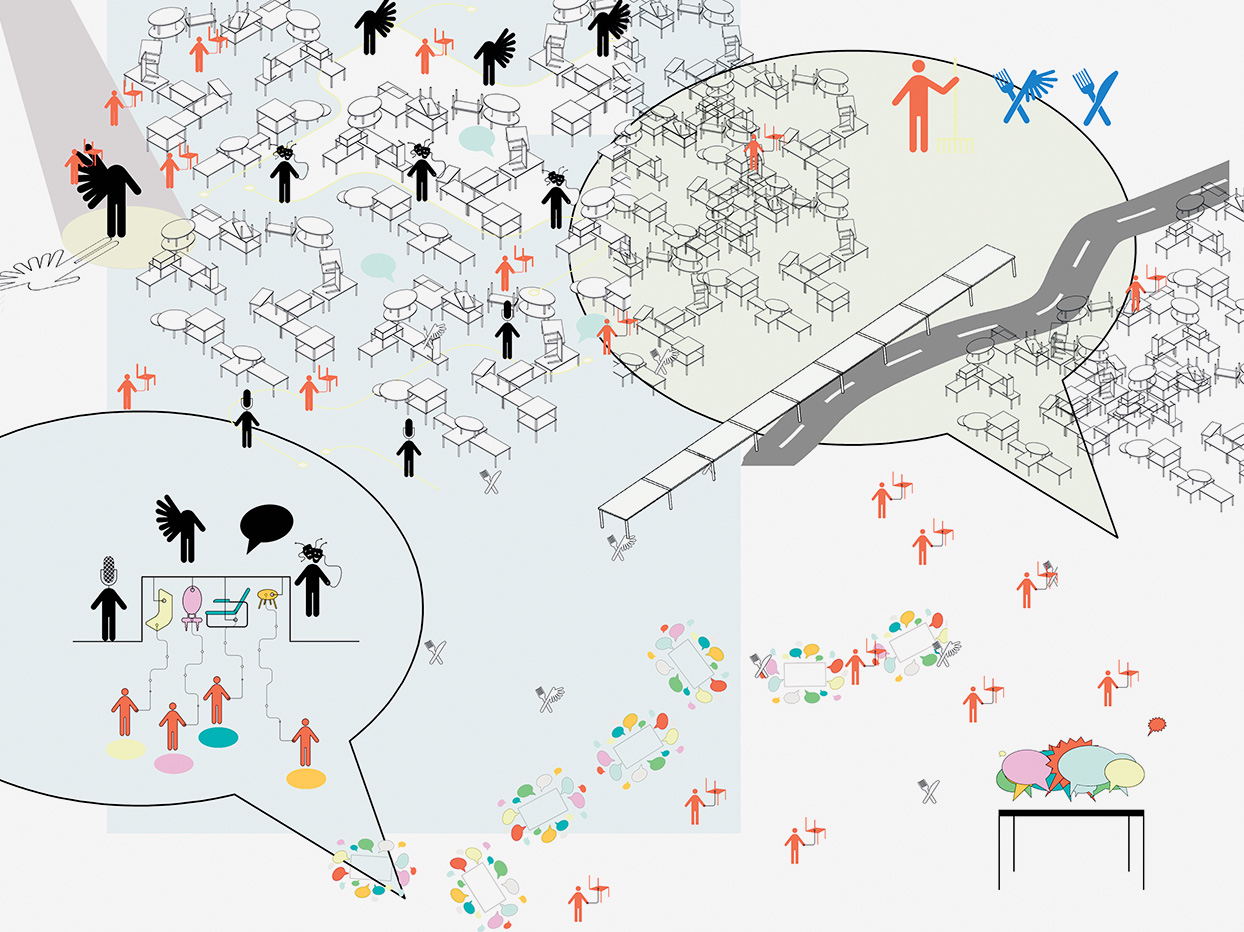

Urban Dinners

'wir essen für das ruhrgebiet’ (We’re eating for the Ruhr region) is a German play of words on the slogan of the Cultural Capital project ‘essen für das ruhrgebiet’ ([the city of] Essen for the Ruhr region). The ‘wir essen für das ruhrgebiet’ project proposes that urban dinners be held simultaneously in neighbourhoods throughout the Ruhr Valley on the longest day of the year. The urban dinners are organized decentrally by and for the neighbourhood residents and the users of the city. Travellers, tourists, down-and-outs, commuters and business travellers are also welcome to participate and dine. The many different cooking cultures, reflecting the multicultural character of the region, fuse and combine to create a new hybrid cuisine.

The tables are laid in derelict spaces throughout the region, the wasteland of the cityscape. Temporary occupation and habitation of this no man’s land reintegrates this space in the regional mental maps and turns the borders of the urban landscape into communicative seams of the cityscape. Theatrical and musical ensembles and other cultural groups from the region roam around on that evening, going from table to table and performing small artistic intermezzos. At exactly the same moment, throughout the whole of the Ruhr Valley, a million voices join in a toast: ‘wir essen für das ruhrgebiet’!

The urban dinner event is organized with the aid of an Internet platform and local media, integrating a diversity of local institutions and activity groups, from ethnic associations to parishes and small cultural communities. Its success as an integrative project is measured by the multiplicity of the forces and networks it manages to bring together. It is a process-oriented project with a bottom-up approach, whereby many local forces within the cityscape are activated. The locally embedded Internet communication platform grows and mutates during this process. The urban dinner, as an ‘inverted event’, is above all an impulse for developing the Neighbours Network City of the Ruhr.

A second urban dinner will be held along the A40 / B1 motorway, the basis of an important network in the Ruhr region and the backbone of the cityscape.

Water Mobili

The post-industrial landscape of the Ruhr is crisscrossed by a complex system of partly derelict waterways. The regional initiative Fluss Stadt Land (River City Land) was set up by 17 cities in the north-east of the Ruhr to upgrade this dense system of rivers and canals, left over from industrial times, into a leisure landscape. The Water Mobili project that we developed for this regional initiative addresses this waterway network. It envisages an array of leisure elements to stimulate the ‘acupuncture points’ on this networked landscape and open it up for leisure society. Given the high unemployment rates, ‘leisure society’ in the Ruhr is primarily a society of involuntary leisure.

The project provides simple modular building components that fit easily into containers which can be moored at specific spots in the water landscape. The modular components can be assembled in all sorts of ways to make camping rafts, floating bars, fishing points, kiosks, exhibition decks, picnic places, floating water theatres, storage or toilet units, cabins, relaxation decks, roofs, swimming pools or other imaginative compositions yet to be discovered.

These pieces of mobile water furniture serve as places for recreation. They are small, floating constructions that add recreational possibilities to the abandoned industrial network of the waterways, thus activating the post-industrial water landscape of the Ruhr.

Hybrid Emscher Landscape

Another important player in the network city of the Ruhr is the Emschergenossenschaft (Emscher Association), founded in 1899 and responsible for water management. It owes its name to the Emscher River, which was used as an industrial sewer. Running through the north of the cityscape, the Emscher sent a stench across the entire industrial hinterland of the Ruhr region.

At present the Emscher Association is working on a project to clean and transform the Emscher into a ‘blue river’ that will flow through the cities and neighbourhoods and be enjoyed by the local inhabitants. The sewage and industrial waste will be diverted underground. Nearly all the sewage from the Ruhr region will then pass through a 51-km concrete pipe which is currently being laid 40m underground, parallel to the Emscher River. A swimming robot will function as an ‘automatic inspector’, monitoring, cleaning and carrying out repairs inside this underground sewage pipe. The pipe will be accessible via entry points distributed at regular intervals along its length.

Our proposal is to upgrade the entrances, which are located at points in the cityscape frequented by many people, into public facilities and exhibition spaces. Together these will form the Emscher Access Pavilions Project. With the aid of these access facilities, the two linear systems – the open stretches of the newly ‘blue’ Emscher and its counterpart, the underground tube – will be connected with the public places and the open spaces of the surrounding cityscape.

These Access Pavilions, designed as special architectural follies, represent the engineering achievements of the Emscher Association and concentrate on exhibitions around the theme of water in general. The Access Pavilions are hybrid spaces, combining architecture and media, and also function as interfaces to a virtual Emscher landscape: one can pay a virtual visit to the amazing underground artefact of the endless concrete tube or fly over and grasp the urban landscape of the Ruhr in a bird’s-eye dynamic simulation. Water stories, urban management news and other local water news also feature in the pavilions programme.

The Pavilions connect the physical linear space of the Emscher River with the Emscher information space. This hybrid environment can also be entered by remote access. Urban, physical and media systems are thus interwoven into a single, large urban network.

SubCity, the Big Urban Game

Like no other region, the Ruhr region has been defined by its ‘underground’, its sub-city. The coal seams were the determining factor for industrialization and hence urbanization. The patterns of the cityscape were based on and shaped by the complex underground networks of mine galleries and shafts. The region is highly conscious of its sub-layers as the foundation and the driver of its cityscape. The memories of this, however, are ambivalent. The deeper layers contain forgotten mining galleries, inaccessible shafts and groundwater lakes, and these are regarded as a threat, reminding people of the many disasters that took place in the past.

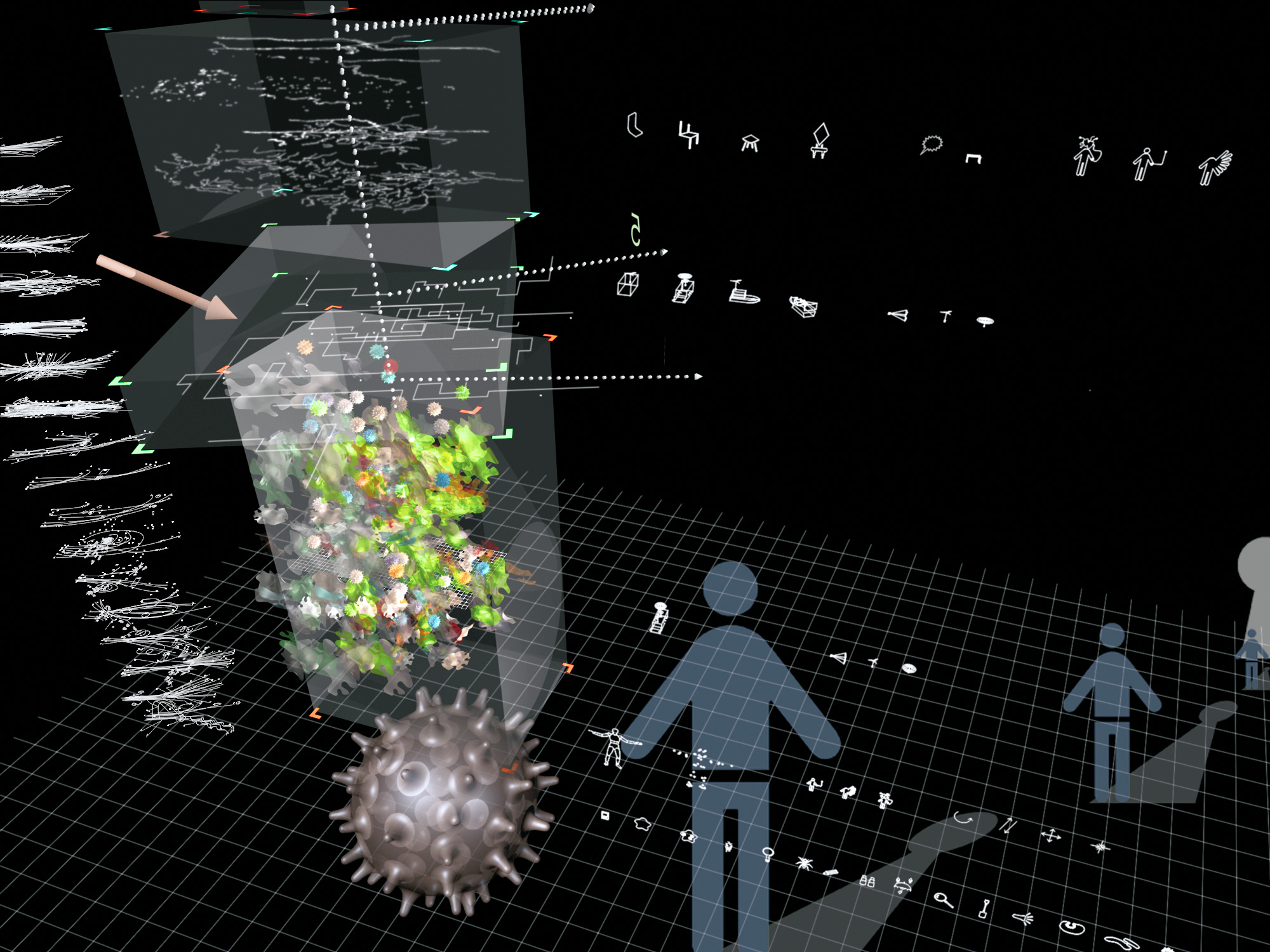

The SubCity game, which we proposed as part of the nnc project, deals with the sub-layers of the city. Using mobile devices, SubCity can be played individually, in groups or even by large communities. The Zollverein colliery in Essen, a World Cultural Heritage site, offers access to the virtual reality of SubCity. Here, in the only remaining functioning entrance to the underground network, one can enter a three-dimensional, interactive media simulation, take part in the networked space of SubCity’s urban dreams and interact with the communal urban substrate.

The game reinterprets and recodes this communal urban substrate. Via a simulation the inhabitants and the visitors of the Ruhr can recreate the deep layers of the cityscape. They can dig virtual shafts and galleries, develop and revitalize an urban underground and live there with their revelations and dreams.

---> roaming the urban network, searching for connections to the SubCity ---> the keyholes to the SubCity are spread around the cityscape: you have to find them ---> the moment you pass through a keyhole you become an actor in SubCity ---> you communicate with your fellow actors and their dreams ---> you exchange and interact using the SubCity tools ---> while interacting you define your avatar, the actor of your dreams ---> you search for new keyholes ---> the moment you pass through another keyhole you become a new actor ---> you redefine your character by interacting with the help of the SubCity tools ---> you pass through the next keyhole ---> you exchange information ---> in search of your docking elements ---> in search of your home

Physical, technical, urban, socio-cultural, virtual and imaginary networks knit the tissue of the Ruhr region. The network city as an open Gesamtkunstwerk.

Neighbours Network City: a project proposal for the city of Essen and the Ruhr region in Germany as the Cultural Capital of Europe 2010 by invoffice for architecture, urbanism and design, Amsterdam, 2004. Project leaders: Elizabeth Sikiaridi and Frans Vogelaar; Collaborators: Chloe Varelidi, Nina-Oanna Constantinescu and Katy van Overzee.

1. Vilém Flusser, Vom Subjekt zum Projekt. Menschwerdung (Frankfurt / Main: Fischer Verlag, 1998 ), 53. First published in Mannheim: Bollmann Verlag, 1994.

2. Vilém Flusser, ‘Entwurf von Relationen’ (interview), ARCH+. no. 111, March 1992, 49.

3. Vilém Flusser, ‘Die Stadt als Wellental in der Bilderflut’, in: idem, Nachgeschichten. Essays, Vorträge, Glossen (Düsseldorf, 1990).

4. Flusser, Vom Subjekt zum Projekt, op. cit. (note. ), 57. The layered, networked space of Neighbours Network City for the Ruhr region, © invOFFICE for architecture, urbanism and design, Amsterdam, 2004.

5. See, for example, publication in Dutch in the architectural journal de Architect, June 1997, cover page and pages 42–47 or web publication in English: mailman.mit.edu.

Elizabeth Sikiardi (the Netherlands) lectures on the design and development of the urban landscape at the University of Duisburg-Essen. Together with Frans Vogelaar she runs invOFFICE for architecture, urbanism and development in Amsterdam.

Frans Vogelaar (the Netherlands) is professor of Hybrid Space at the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne. Together with Elizabeth Sikiardi he runs invOFFICE for architecture, urbanism and development in Amsterdam.