The Audio-Hallucinatory Spheres of the City

A Pop Analysis of the Urbanization

November 1, 2005essay,

Under the name Studio Popcorn, architect Alex de Jong and jurist-philosopher Marc Schuilenburg research the effects of urbanization processes. They argue for the inclusion of processes other than physical, spatial ones in the scope of research on urbanization. This article focuses on the rise of an intermedial space, which includes contemporary popular music and its associated urban culture, and which plays a crucial part in today’s urbanization processes.*

‘Your Place or Mine?’

In the video clip Drop It Like It’s Hot (2004) by rappers Snoop ‘Doggy’ Dogg and Pharrel Williams, the city sparkles large as life. ‘Snooop Daawg, click-clack-click-clack, Snooop Daawg’ the beat sounds, with tongue clicks made by the two superstars. The sonic minimalism of the number is echoed in the video images of the clip by director Paul Hunter. The rappers stand in a black-and-white decor which alternates with a backdrop of their favourite urban icons: a black Rolls Royce, a lowrider trike, a jewel-studded belt, cell phones and Ice Cream sneakers. Remarkably, the clip evokes an urban experience in the viewer without literally displaying typical features of a city such as buildings and squares.

The absence of monuments like buildings, bridges or squares in the clip is remarkable. Today’s global economy, in which cities compete world-wide for visitors and trade, places ever more emphasis on the concrete design of the city’s physical space. ‘Old’ cities cautiously expand their urban icons, while ‘young’ cities invite internationally renowned architects to set down a new repertoire of buildings. The result is termed Postcard Architecture. Postcard Architecture offers cities a chance to distinguish themselves from one another qualitatively. Then every city has its own, unique static ‘skeleton’ of buildings, streets and plazas. Postcard Architecture holds out the suggestion that the quality of a city depends on the characteristics of its location and the appearance of its main buildings. In combination, these two hallmarks represent the permanent character of a city. The ‘soul’ or identity of a city lies in the layout of its streets, the image of its buildings and the size of its public spaces.

Although no buildings, streets, bridges or squares are to be seen in the video clip of Snoop Dogg and Pharrell Williams, it cannot be denied that the images provoke an urban experience. To put it more precisely, showing a Rolls, a lowrider trike, jewelled belts and cell phones creates a specifically urban spatiality in which the rappers play the leading role. This observation raises the following question: what urban spatial qualities can be distinguished apart form the physical space of the city? We pose this question against the background of the increasing urbanization of our physical surroundings. This urbanization process is taking place pell-mell, as is evident from the perspective of our living conditions. Although in 1900 there were only eleven cities in the world with over a million inhabitants, by the beginning of the twenty-first century the number of cities with over three million inhabitants had already topped one hundred. Over ninety percent of the world’s population will live in cities or urbanized areas within twenty years from now. Distinctions such as ‘centre’ as opposed to ‘periphery’, or ‘country’ as opposed to ‘city’ are becoming increasingly obsolete.

Snoop Dogg's and Pharrell Williams’s clip demonstrates that the urbanization of our living environment is not merely a product of physical space. The urbanization process takes shape also by virtue of other spaces. Therefore problems such as whether, and by what means, new urban spatialities can be distinguished are relevant for specifying that urbanization process more exactly. The ideas of the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk offer several leads in this respect. Since prehistory, people have been marking out their environment by producing sounds, which function to establish a difference between the group people belong to and their immediate surroundings. The group encloses itself, as it were, in a globe of sounds and noises. Sloterdijk terms these environments ‘spheres’. What implications does the notion of spheres have for the introduction of new urban spatialities? This question will be considered in detail below in relation to the architecture of Archigram, the social space of Detroit Techno, and the intermedial space of youth culture’s current coolest adjective, Urban.

Space in History: ‘Please Can We Have Our Sphere Back?’

The organization of space is a fundamental dimension of the urbanization process. Space was long conceived of only in the physical sense. From that perspective, space is seen as an entity detached from objects and subjects. Physical space becomes the objective stage on which social processes play out and on which objects are localized.1 The German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk criticizes this outlook in his ‘Spheres’ studies by arguing that the oldest, most efficient method of creating a space was to use sound. The ‘Spheres’ trilogy deals with the history of mankind and the ‘place’ man has occupied in the world through the ages. The traditional philosophical question, ‘What is man?’ is here no longer primary; to Sloterdijk, the question ‘Where is man?’ is more important. In an attempt to answer this question, he compares prehistoric mankind living in small groups to survivors of a shipwreck, bobbing around on the open sea on improvised rafts. Without recourse to flotsam, the prehistoric survivors would have roamed around the measureless landscape in relative isolation. Although prehistoric people lived in relative harmony with their environment, they needed sound to mark their difference from their environment. By murmuring, singing, speaking and clapping, members of the group created a difference between themselves and the world around them. The sounds also created a bond between members of the group because they had a recognizable character and a unique pitch. Each group had a distinct tonality, while the size of the inner world was determined by the reach of their voices.2 The sounds ensured that the members of the group lived in a continuum of permanent mutual audibility and visibility.

Sloterdijk argues that for prehistoric man, living in small nomadic groups and surrounded by a formidable natural world, a good sphere was a sphere of survival. The oldest meaning of the word sphere comes from the Greek sphaira, meaning a globe or ball. The globe is thus the fundamental shape of a sphere. In a more general sense, a sphere is a spherical experiential space shared by two or more people in a close mutual relationship. In surroundings perilous to its members, the globe of sound provided a protective haven for the group. It formed a space that shielded the group from external dangers. But returning to the central question, what do these shared spatial constellations imply for the urbanization process? What new spatialities arise from the auditory spheres?

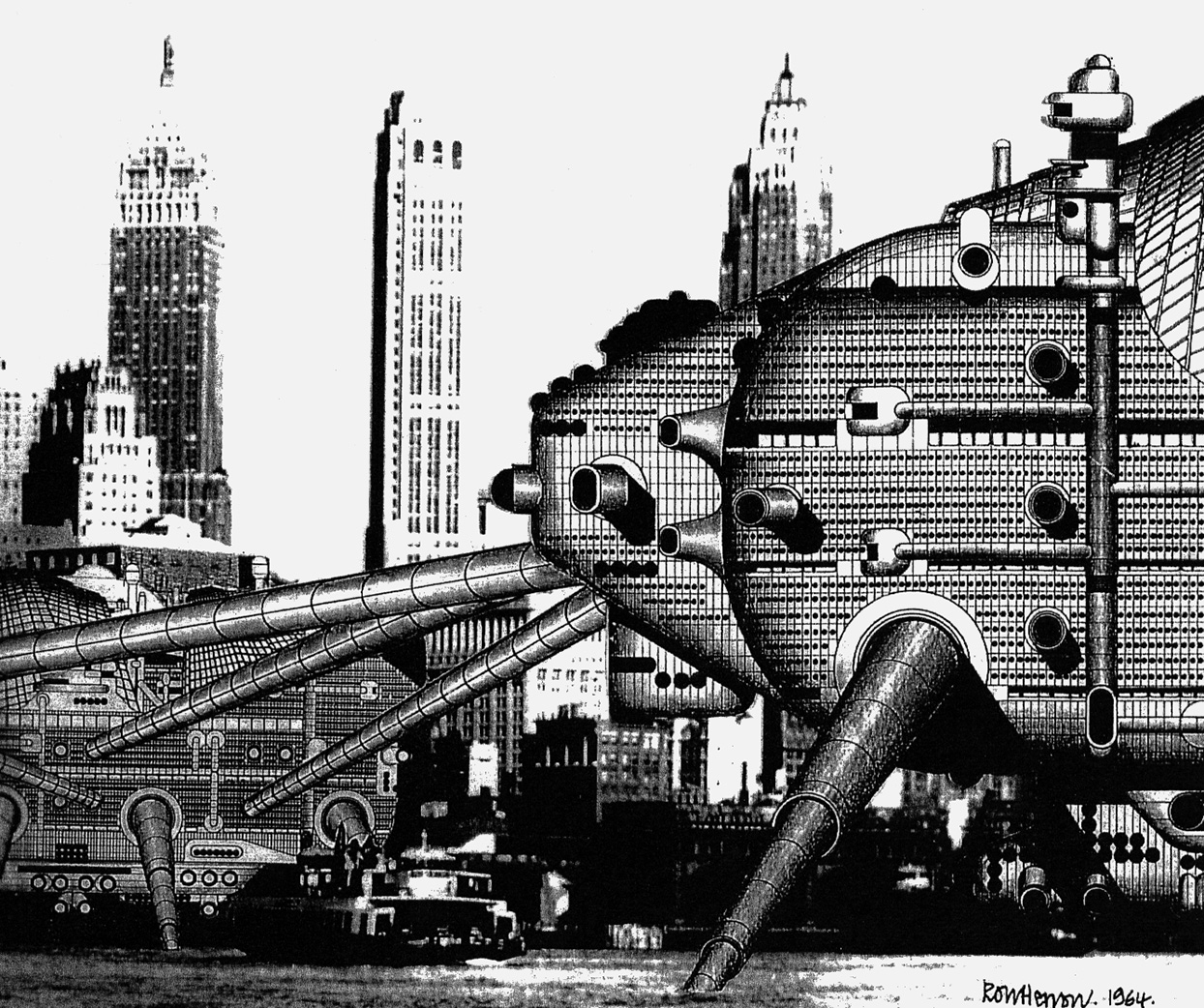

We could say that the architecture of the British Archigram group gives a first hint in this direction. In the early 1960s, David Greene, Warren Chalk, Peter Cook, Mike Webb, Ron Herron and Dennis Crompton, a group of architects from Hampstead, London, designed a series of capsules and globes that enabled the inhabitants to form a closed community within the physical space of the city. The designs were the outcome of the manifesto in which they expressed their impatience and dissatisfaction with the narrow outlook of architectural practice at the time.3 The architects wished to put an end to the dominance of the commercial, mainly functional architecture with which England was being rebuilt after the Second World War. In their view, this architecture was incapable of accommodating the possibilities of the information society they saw approaching. The group called for an architectural and planning practice that related to new forms of technology and the abundant creativity of popular culture. The manifesto was titled Archigram, a contraction of ‘architecture’ and ‘telegram’. The group hoped to realize the potential of a fusion of technology and architecture. This fusion was to lead to the liberation of mankind from his constrictive, coercive environment. Architecture was a means of becoming independent of the inexorable structure of physical space. Steamers, trains, cars and motorcycles would no longer be needed. They were symbols of the machine age. The new information age would be dictated by space capsules, robots, computers and projection screens.

Inspired by the designs made by Richard Buckminster Fuller in the 1950s, Archigram designed a series of spherical capsules to meet all the needs of their inhabitants.4 A good example is the Living Pod project, which takes the form of a lunar module. The skin of the lunar capsule contains all the facilities that are present in houses. But above all, the capsule makes it possible for the inhabitants to move through a hazardous outside world in the shelter of their interior. Independently of its environment, the globe can be placed anywhere. In the Capsules design, multiple capsules are attached to a continuous vertical concrete core. A crane is available at the top of the structure to hoist up a new globe and link it to the core whenever required. In another design, Blow-Out Village, capsules are attached to a fan of telescopic arms and float above the surrounding landscape at various heights. The arms also support a large transparent dome, which can be stretched over the landscape. Using these globular, movable designs, the Archigram members created sealed interior worlds that are autonomous and context-free. From then on the globe-dweller controlled his own faith. Prehistoric man has for Archigram evolved into the ‘Boy in the Bubble’, surrounded by popular gadgets, who has swapped his sonic sphere for a high-tech habitat cell.

The Disconnection of Archigram

Archigram thus wanted to provide the inhabitants of modern cities with greater freedom of movement within an environment they themselves could shape. In addition to this, they believed that innovations take place in domains outside architecture: space travel, packaging, communications media and the vehicle industry. ‘The prepackaged frozen lunch is more important than Palladio,’ Peter Cook said in 1967. The machines adulated by modernist architects of the 1920s have long become commonplace. The scope of architecture, according to Archigram, should reach beyond its bureaucratic limitations and elite aesthetics. Architecture had to be expanded to include the various aspects of cultural production, such as could be found in the seething culture of pop and the revolutionary technologies of space exploration. Only by establishing connections between objects, events, technologies and media could the territory of architecture blend in with everyday life.

Now everything has become architecture. Durability and identity, the hallmarks of Postcard Architecture, do not have to be associated only with buildings or public spaces. Hot air balloons, landscapes and space capsules are also architectural entities. That means that Archigram’s use of geographical space is less and less firmly attached to its concrete layout. In Moving City, the whole city has disappeared into a mobile capsule. Must we draw the conclusion that the city is placeless? For Archigram the city is no longer permanently fixed, as Postcard Architecture would suggest. It has become above all portable. Clumsy, fat, steel insects crawl around on retractable legs, and dock like ocean liners at old, static cities such as New York, London or Amsterdam. Arriving in the deserts of Egypt, they make even the pyramids look like tiny toys.

Since the layout of physical space became less and less important, Archigram’s designs were no longer restricted to globe-like forms. The radical development of information and communications processes, in particular, dematerialized the literal interpretation of a sphere ever further in their thinking. Armed with satellite dishes and space technology, Archigram’s Tuned Suburb demonstrates that the residents of a suburb can have the same intensity of experience as in the centre of a metropolis. Themes such as invisibility, weightlessness, temporariness and portability started taking a central place in their presentations of city designs. Architecture was removed ever farther from the domain of the city, to be replaced by subtle links between various media and activities. Against this background, architecture served to establish interconnections in projects like Quietly Technologised Folk Surburbias, Crater City and Hedgerow Village. In 1962, Buckminster Fuller had proposed building a geodesic dome over an area of Manhattan from 64th Street to 22nd Street to protect the inhabitants from air pollution, but Archigram no longer needed the material globe. They created spaces which become urban as soon as the occupants logged in, as demonstrated by Plug-In City.

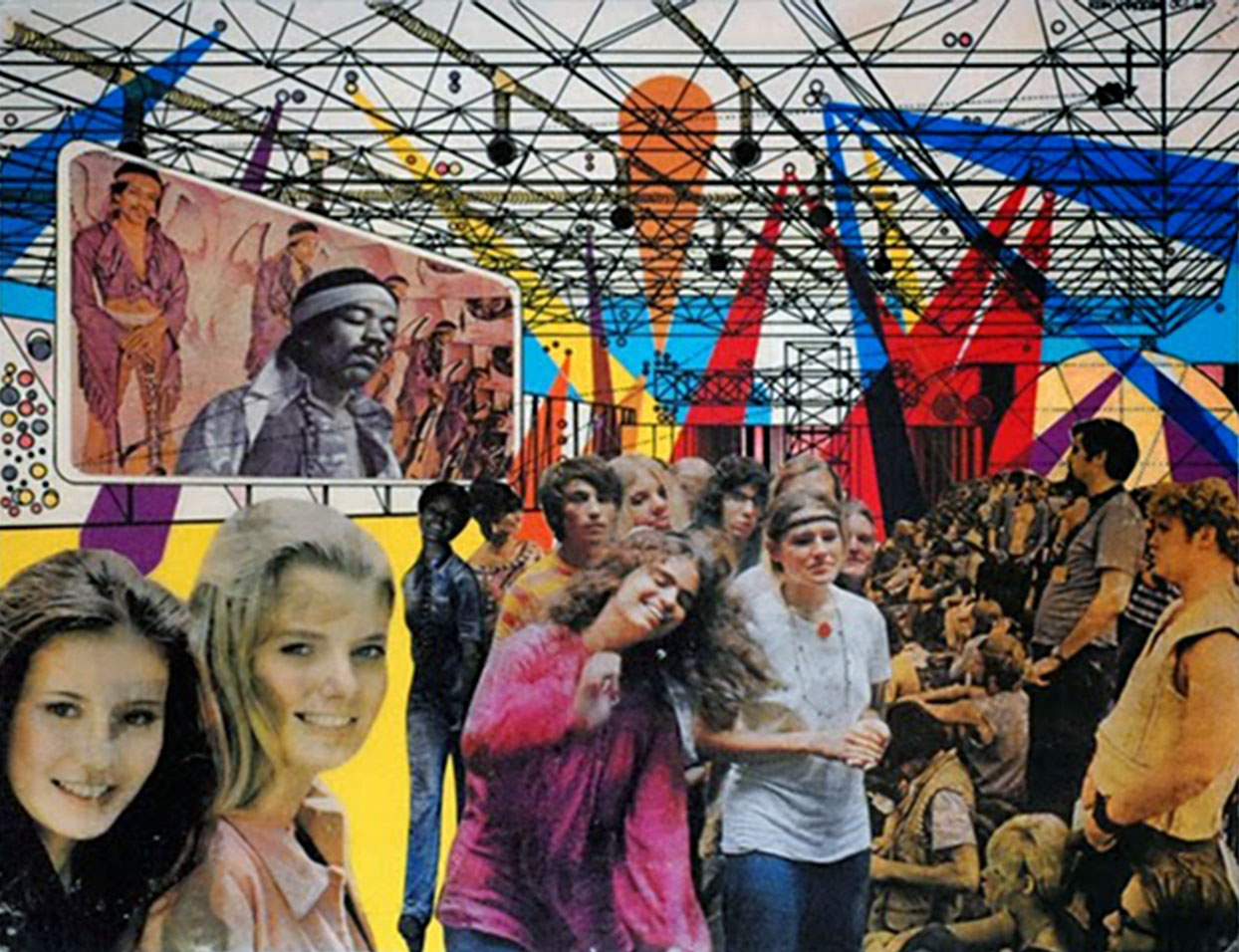

With underground buildings, weightless balloons and communications technology, Archigram created interior spaces that were held together by invisible wires and tunnels. What they achieved reached a climax in the competition design for an entertainment centre on an area of reclaimed land off the coast of Monaco. Archigram proposed creating an underground dome with a park on top of it. The roof, planted with trees and lawns, had service openings on a six metre grid. Visitors could plug in parasols, telephones or tvs to connect with services in the building underneath. Below ground, the design provides a hall large enough for ice-hockey matches, circuses and rock concerts.5

But the only scheme by the group that stood any chance of being built alas ran aground on problems with the groundwater during excavation of the construction pit. The lack of political backing put the final nail in the coffin of the project. However, more important than the non-realization of the project was the attention it drew to the rising importance of information and communications technologies (ict) in the layout of urban space. Tribes that once lived separately from one another in prehistoric times, as described by Peter Sloterdijk, were now able to communicate through networks of road, air and sea routes, by Internet, satellites and cables. Distances have grown ever shorter due to the inception of these global networks of computer links and information technologies. Yet despite the global scale and spread of ict, the impact of the associated social processes in physical space must not be forgotten. Every social grouping you belong to has a spatial dimension. The core of society turns on the relation between inside and outside, between what’s hot and what’s not. How can the spatiality of this ‘immune sphere’, as Sloterdijk calls it, be further analysed?

Detroit: A Different Sound, a Different Space?

Sloterdijk’s dislike of popular music prevents him from connecting the spatial aspects of human society to the pop and media culture. He condemns the offensive of the ‘sound media’ because global popular music contributes, in his view, to the stripping away of the world community’s sonosphere.6 In unmistakable terms, he lumps all music together. He holds that the amusement music of the West, following a period of absorbing influences from musical styles of the East and the South, is now developing a mass of vulgarly musical universals which have gained worldwide acceptance. Popular music has reached the point, according to Sloterdijk, where it purveys the same rhythmic and harmonic formulas in every corner of the globe. It has every loudspeaker on the planet churning out the same musical imperatives, the same titillating effects, the same standardized phrases and the same tonal formulas.7

There is little doubt that popular media indeed have a considerable homogenizing power nowadays. The sounds around us no longer originate purely from the human body or from nature. New media like television, the Internet, mp3 players, iPods, radios and other audio equipment have replaced the old media of clapping, singing and babbling. Sloterdijk argues that these new media launch an unprecedented attack on the ears of the world. Yet the fact that the same musical imperatives are repeated over and again in pop music can hardly be called problematic. Not only does a changed context for a quotation or sample automatically lead to a new interpretation, but the repetition of tonal phrases, effects and formulas is one of the most essential ingredients of pop music. Music moreover constructs a coherent social space in which a communal atmosphere develops among the hearers. This psycho-acoustic sphere is characterized by a double motion. It arises as a consequence of the being together by members of the group, but at the same time it brings them together. Doesn’t every group (hooligans, architects and so forth) create its own refrain? The group is portrayed as unified by means of the sound, while the individual members can also see themselves as part of the group.8 The consequences this has for the urbanization of our habitat, is apparent in one of the first electronic dance cities, Detroit.9

Techno emerged in the 1980s in nightclubs and radio broadcasts, with record labels, producers and DJs. It combined the industrial sounds of the white German group Kraftwerk with New York synthetic disco and with the futurism in the black music of such artists as Sun Ra, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis and Funkadelic. One of the best known producers is the two-man team of Juan Atkins and Rick Davis. In 1984, operating under the name Cybotron (a partial contraction of cyborg and electronic) they gave Detroit the nickname it still has today: Tech-noh Cit-eee, yells the distorted voice of Rick Davis in the eponymously titled number, which is about the new condition of Detroit after the departure of the car industry and the race riots of the late 1960s. That the city had broken down into separate enclaves in the huge areas of asphalt and abandoned factory sites was not, for Atkins and Davis, reason for moping about the decline of the city and the loss of its mainstay industry. ‘You can look at the state of Detroit as a plus,’ Atkins has said. ‘We’re at the forefront here. When the new technology came in, Detroit collapsed as an industrial city, but Detroit is Techno City: it’s getting better, it’s coming back around.’

The consequence is that the music of groups, producers and DJ’s like Cybotron, Model 500, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson no longer went in search of the ‘soul’ or identity of Detroit. The many aliases Kevin Saunderson has used to sell his music, including The Bad Boys, E-Dancer, Esray, K.S. Experience, Inter-City, Inner City, Kaos, Keynotes, Master Reese and Tronikhouse, made the city seem bigger than it really is. It was no longer the name of the artists and the sensibilities of the musicians that mattered, but, according to Derek May, a distinctive flavour: ‘It’s the emptiness in the city that puts the wholeness in the music. It’s like a blind person can smell and touch ad can sense things that a person with eyes would never notice. And I tend to think a lot of us here in Detroit have been blind: blinded by what was happening around us. And we sort of took those other senses and enhanced them, and that’s how the music developed.’ Detroit techno hence drew lines between a given impression and an idea that is not yet present. The distinct flavour was created by linking hallmarks of the sound to the city. After the city’s loss of a coherent visual unity, the techno sounds created a collective auditive envelope. In other words, they constructed a social space defined by singular events (such as raves and block parties) and popular media. This social space ensures that the listener forms a mental image of the city behind the sounds.10

In other words, social processes provide a form of mutual coherence. The social space of Detroit techno was related to dimensions of direct experience and perception. Not only did the rhythm make you dance spasmodically like a robot, but the music made the city into an immediate experience without all its inhabitants having to come together physically. That is why driving along an empty highway through a deserted neighbourhood to the music of Cosmic Cars (1982) was for Cybotron a no less than sensational auditory experience: ‘Stepping on the gas. Stepping on the gas in my cosmic car.’

A Sonic Grid

The musical sounds and the noises which Sloterdijk designates, using a term from the Canadian composer Murray Schafer, as the sonosphere of a group, pull techno fans into the interior of a psycho-acoustic sphere. What matters here is that this social space is a different kind than that which we perceive as physical. While the individual is always at the centre of a sonosphere, physical space has long been regarded as an objective stage or absolute entity which is analysable independently of time and matter. In that interpretation, the observer and the observed stand facing one another, so to speak, with a (neutral) space between them.11 The ear has no ‘opposite’, however. The ear does not have a frontal view of a distant object. In relation to musical sounds and noises, physical space must therefore be considered in combination with social processes. But, social processes and spatial structures cannot be understood independently of one another.12 To put it in other terms: sounds and noises confirm the existence of the city and have a community-establishing quality.13

Seen from this perspective, the city is not only placeless but also time-bound. Because a city is able to come into existence at any moment, it no longer needs fixed coordinates or points. We can only hold that our urban environment is a history of spheres or shared spatial constellations. In Sloterdijk’s words: ‘Anyone who is in the world, is also in a sphere.’ The way the social processes actualize a spatiality becomes clear in relation to the history of the popular culture of techno. The term ‘techno’ originated from The Third Wave (1980), a book by the American futurologist Alvin Toffler. He used the term to designate the most important people of the cybernetic era. In The Third Wave, Toffler describes the history of human civilization in terms of three waves of change. The first wave was the agricultural revolution, which needed over a thousand years to reach its full scope. The second wave was the industrial civilization of factories, standardization, specialization and mass production. During this wave, which lasted over three hundred years, a separation took place between producers and consumers. Now, according to Toffler, the wave of information technology is beginning to wash away traces of the second wave. After the agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution, the digital revolution with its computers and communication networks is the third fundamental change in human history.

Inspired by Toffler’s ideas, Atkins and Davies saw in early video games a demonstration of how urban spaces can take shape in the digital era. The spatial framework of the video game offered new possibilities to meet one another in different ways. The framework provided an open system of connections which Atkins and Davies called the Grid: ‘We used a lot of video terms to refer to real-life situations. We conceived of the streets or the environment as being like the Game Grid. And Cybotron was considered a ‘super-sprite’. Certain images in a video programme are referred to as ‘sprites’, and a super sprite had certain powers on the game-grid that a regular sprite didn’t have.’14 The multiple spatial dimensions of video games lead to numbers like Alleys of Your Mind, Cosmic Cars and Clear. But it is in Techno City that a coherent, inspired space is opened in which sound is the most imaginative and connective element for the formation of an urban spatiality.

Techno City was Atkins and Davies’ answer to the film Metropolis (1926) by Fritz Lang. Metropolis was filmed in the ufa Neu Babelsberg studios near Berlin, and had its premiere on 10 January 1927. The film is about the inequality between employers and workers, but is best known for its dazzling backdrop of soaring skyscrapers with crowded highways bridging the gaps between them and aeroplanes filling the air space. Metropolis is for Davies the ultimate proof that a city that is subject to physical laws can also be evoked by the ephemeral character of a soundscape: ‘Techno City was the electronic village. It was divided into several sections. I’d watched Fritz Lang’s Metropolis – which had the privileged sector in the clouds and the underground worker’s city. I thought there should be three sectors: the idea was that a person could be born and raised in Techno City – the worker’s city – but what he wanted to do was work his way to the cybodrome where artists and intellectuals reside. There would be no Moloch, but all sorts of diversions, games, electronic instruments. Techno City was the equivalent of the ghetto in Detroit: on Woodward Avenue the pimps, pushers etc. get overlooked by the Renaissance Tower.’

All in all, Detroit’s techno shows that the process of urbanization does not take place in a physical space only. That is why a distinction must be made between a physical and a social space. Social space refers to the spatial characteristics of spatial processes.15 From this perspective, the question of being together in the city and the place of the city becomes ever more relevant. If sounds draw a boundary between inside and outside, and create an ‘immune system’, we are obliged to rethink the relationship between the different spatialities in the city. After all, where are we when we are in the city? What are the inner worlds of the spheres of the city?16

Urban: A New Urban Spatiality?

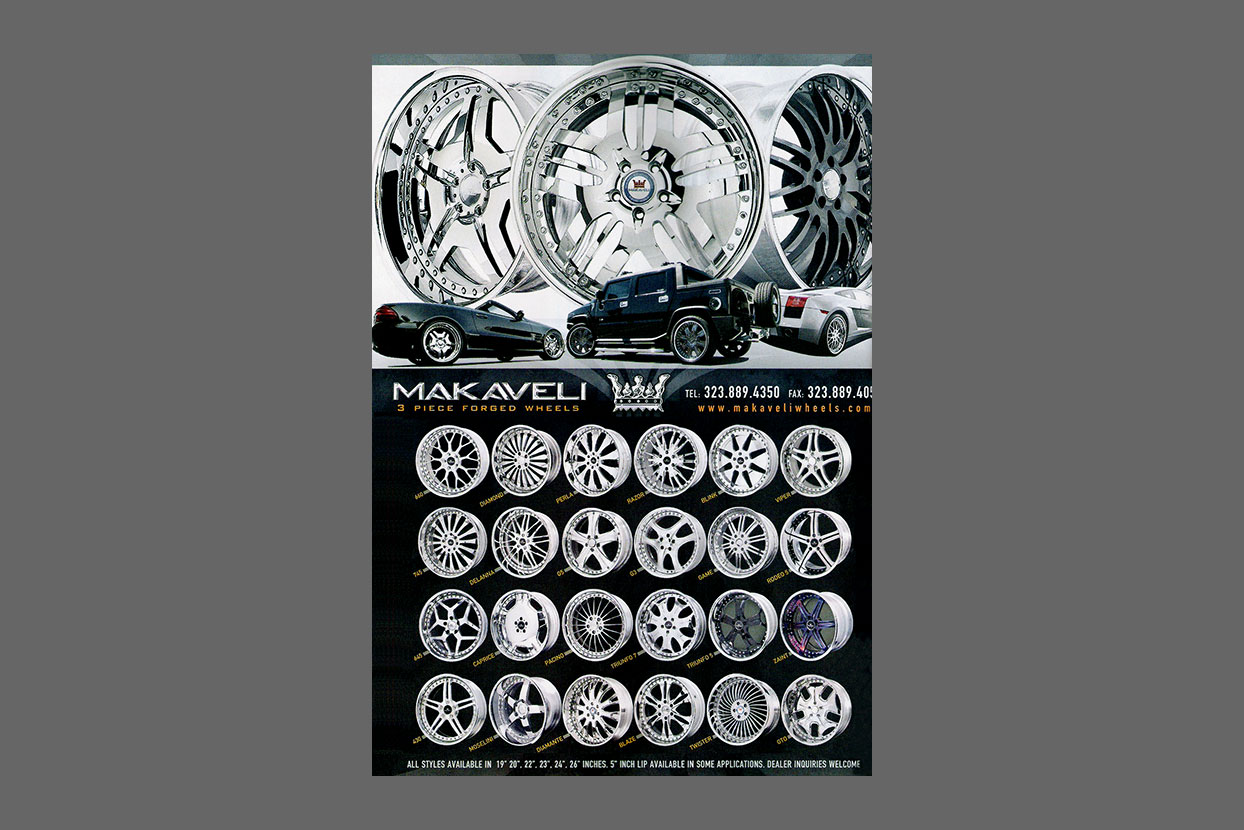

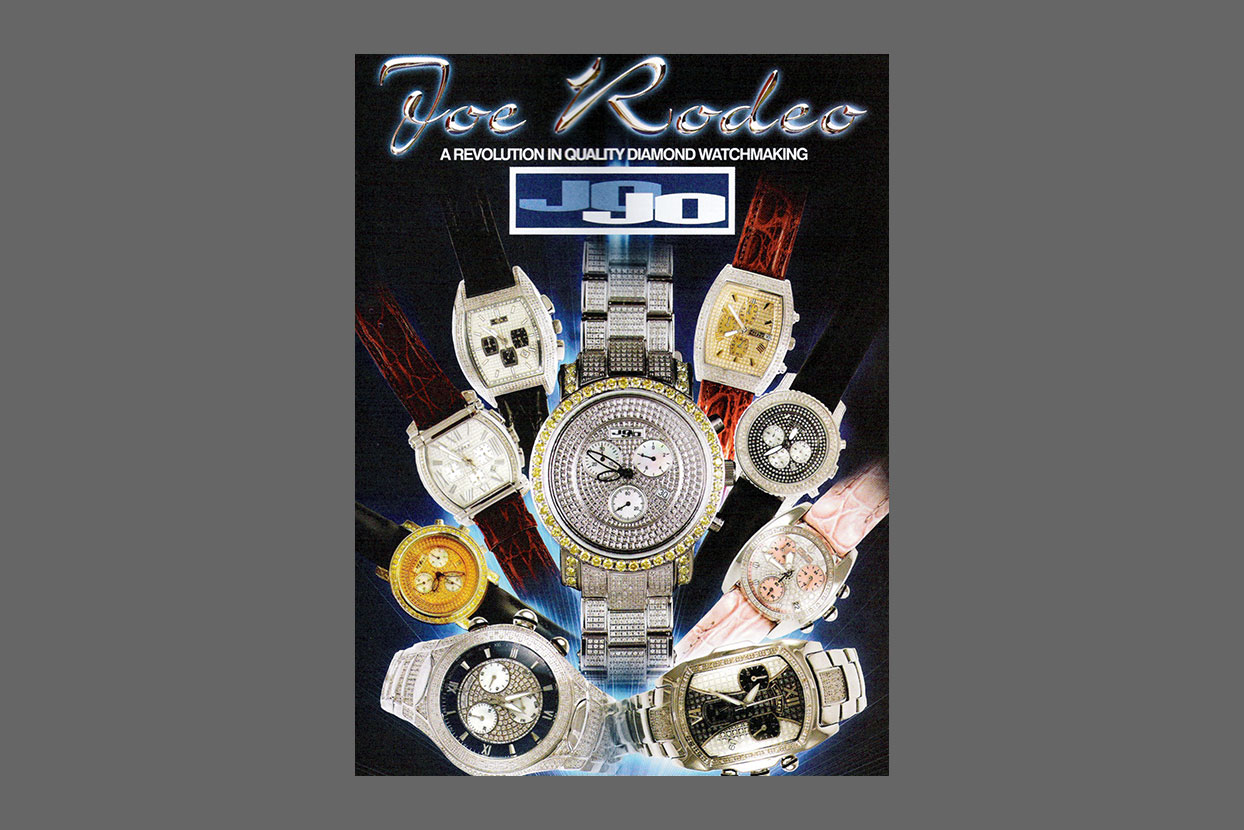

What then is the problem of Archigram and Detroit? Is it how to rescue the city? Or how to get rid of the city? Whatever the case, their similarities are striking. They share their fascination in a city that has become detached from the concrete layout of its space. They are not alone in that. The city is brought increasingly into connection with a colourful mass of products and activities, which range from musical styles, clothing, perfumes and jewellery to sneakers. The sheer size of the city's sphere of influence is easy to demonstrate. Baggy denim trousers with oversized details such as zips, buttons and sewn-on pockets are called Urban Jeans. Urban Lingerie is the trend that combines ultra-feminine underclothes with the brawny clothing style of hip hop. Sunglasses in the Adidas ‘Kill Loop' line mix trends in sports clothing with the raw energy of the street; not surprisingly, they are referred to as Urban Sunglasses. Urban jewellery means watches, belts and chains glittering with gold and diamonds. In hip hop culture, an Urban Car is a four-wheel drive suv, preferably a Cadillac Escalade. Afro-Americans make Urban Entertainment on the theme of ‘life in the big city'. Urban Skating, Urban Golf, Urban Climbing, Urban Freeflow, Urban Base Jumping, Urban Street Racing, and Urban Soccer are the latest sports. And Urban Arts refers to art forms varying from graffiti, stickers and posters to various kinds of street dancing.

But despite the evaporation of the city's concrete, spatial structure, which is so evident from the ‘urban' associations evoked by these products and activities, the city still remains recognizable. Perhaps that's the problem. Why does the city remain so identifiable, despite all these marginal but otherwise highly diverse products and activities? And how should we read its identity? Much of the answers to these questions, which are based on the assumption that the city is placeless and time-bound, is located in the intermedial space of the city. This observation brings us to the core of this article. We hold that the youth culture called Urban marks the rise of a third urban space, which can serve as a background to the debate about urbanization processes.

Various authors have argued that Urban is misjudged whenever it is used as a synonym for ‘minority culture'. Despite the equation between ‘minority' (read ‘black') and ‘urban' ignores the diversity of the forms in which it is expressed, there have been signs of ‘urban culture' having been appropriated by hip-hop and post-hip-hop culture since the mid 1990s.17 Although the collective term ‘urban' is related to the Latin word ‘urbanus', which means ‘town' or ‘urbane', the term is used mainly to designate the meaning-space of hip-hop and r&b.18 In that space, youth culture's trendiest epithet is linked to minorities who have developed the art of surviving the streets of the poorest quarters of the biggest cities. The street is the source of all wisdom, and the place where realness, trust, authenticity and credibility are still to be found. Not only does the street stand for ‘the real', but belonging in this environment is a source of ‘street cred'. ‘I'm still Jenny from the block ... I know where I came from (from the Bronx)!', Jennifer Lopez sings in Jenny From the Block (2002). The identity of the star coincides with that of the ‘gangstas', ‘pimps', ‘bitches' and other ‘playas' of the cities of the usa.

At first sight, then, it seems that life in the physical space of the city is once again dominant. Yet the history of the 'urban empire' gains a wider perspective when a new urban spatiality is created by a sophisticated product and marketing mechanism. A most instructive example of how that merchandizing leads to a shared spatial construction is presented by the story of the Simmons family. The well-educated Russell Simmons grew up during the 1960s in Hollis, a mixed but largely middle-class neighbourhood in the borough of Queens, New York. His younger brother, Joseph, who was later to gain a name as ‘Reverend Run' of the Run dmc rap group, describes the neighbourhood as ‘nice homes, manicured gardens and everything'.19 While a student at City College ny, Russell Simmons organized hip-hop parties, but he gained national recognition in 1984 when he launched the record label Def Jam together with Rick Rubin. Simmons did not restrict himself to issuing records by LL Cool J, Beastie Boys, Public Enemy and epmd. Six years later, he set up the company Rush Communications which may be regarded as one of the founders of the present Urban culture. The company has various subsidiaries. Besides making live shows, tv programmes, magazines and energy beverages, it markets the products of Phat Fashion, a clothing brand with street credibility. Phat Fashion describes its clothes style as ‘a mixture of the hip-hop culture of the streets and the preppy culture of the Ivy League'. An important sales group for these products is indeed formed by students of the Ivy League universities, a cluster of top-ranking universities in the North-Eastern United States which have long been a byword for high-quality education and social prestige. Phat Fashion is divided into the sections Phat Farm, BabyPhat and Phat Farm Kids. Phat Farm is the male clothing line, while Baby Phat, headed by Simmons's wife, the former Chanel model Kimora Lee Simmons, targets wealthy young women. Phat Farm has been sold for $140 million to the clothing giant Kellwood Co. The diversity of Rush Communications is evident from the fact that besides owning several fashion lines, they run a non-commercial network that organizes congresses throughout America with the aim of raising political consciousness and voting turnout among the black population. The company also promotes the Rush Card with which they hope to reach 45 million Americans who do not have a personal bank account or credit rating. Owning one of these prepaid cash cards is supposed to make people less dependent on cheques and post offices for making payments. The card costs $20 and each transaction costs $1.

The positioning of the Urban tag gained substance when Russel Simmons' brother, Joseph ‘Run' Simmons, started the rap group Run dmc with Darryl ‘dmc' McDaniel and Jam Master Jay. Although the members of Run dmc come from suburban Hollis and not the violence-ridden ghettos of New York, they spurned their privileged background in their lyrics. Rick Rubin, cofounder of Def Jam, explained their relation to the street as follows: ‘With Run dmc and the suburban rap school we looked at ghetto life as a cowboy movie. To us, it was like Clint Eastwood. We could talk about those things because they weren't that close to home.'20 Their customary garb of black clothes with white Adidas sneakers came about after a performance in The Bronx, where the audience jeered them for their clothing and their origins in the ‘soft' borough of Queens. They spent the first money they earned from their records buying the latest fashions on Jamaica Avenue. A few years later they had a breakthrough to popular success with the song Walk This Way (1986) and their hallmark outfits.

The influence of entertainment corporations like Rush Communications, which connect the seamy side of life in the big city to products as diverse as fashions, shoes, debit cards and congresses, is hard to overestimate. The close-knit bond of the street and commercial success is also proven by the success of the la Bloods gangs affiliated Death Row record label run by Suge Knight from Los Angeles. Death Row’s top star, Snoop ‘Doggy’ Dogg put in an appearance on the tv programme Saturday Night Live wearing a Tommy Hilfiger shirt.21 Until Snoop Dogg’s gig, the Hilfiger market profile was not unlike that of Calvin Klein. Hilfiger clothes were mainly worn by middle-aged white men in Central usa. But after Snoop Dogg’s tv performance in 1994, sales of the brand shot up by $90 million. Tommy Hilfiger then started designing looser, more casual clothes to meet the ‘street wear’ norms of the large cities on the American East and West Coasts. Snoop Dogg did not appear on tv only in his capacity as a musician. He also likes to act the fashion model and to make play of his gangland associations, having been jailed several times on suspicion of complicity in fatal drive-by shootings. Unlike American politicians, the Californian rapper uses his shady reputation to bolster his credibility. His intentions are unmistakable in the title of his third album, The Game Is To Be Sold Not Told (1998).

‘Urban Empire’: An Intermedial Space

The question of being together in the city and the place of the city remains undiminished in force in the Urban culture. If spheres create a boundary between inside and outside and so institute an ‘immune system’, we are forced to rethink the relation of physical urban space to social urban space. As we saw earlier with Archigram, information and communications technologies give coherence to interior spaces and create a new architecture. This same information and communications technology makes it possible for tracks like Techno City and Cosmic Cars to actualize a coherent, shared urban spatiality at any moment. What is it that unites the cluster of products and activities ranged under the tag Urban? What sphere holds together the urban spatiality that Snoop Dogg and Pharrell Williams’ clip Drop It Like It’s Hot aims to project? We call the configurations of spheres that emerge within current youth culture intermedial links. The Urban realm not only creates a seductive sound world that makes the city conceivable and apprehensible in a different way, but also binds a symbolic world to its sounds and rhythms. Clothes, cars and jewellery are ‘charged’ objects because they actualize an audiovisual meaning of what the city stands for. Does the Urban tag thereby evoke a different urban space between the users and the various media?

Despite the fact that Urban culture depends only partially on the ‘roots’ of its existence, it demonstrates that the city cannot be conceived of solely as a set of ‘artefacts’ which are connected to an urban environment and which derive their meaning from a given historical context.22 The city is also substantiated outside of the concrete layout of its physical space and the associated social processes. The foundation of a given city is thus no longer a once-only event; after all, that would mean that it was fixed once and for all. A city takes shape over and over again because it proves to be an effect of various medial processes. It is in this relation of the user to the media that surround him that the spectator’s perception is central. The activities taking place between different senses form the dynamic basis of an urban experience for the spectator which is evoked by various products and activities. Without losing its credibility, the city emerges between the sunglasses, cars, lingerie, jewellery and clothes of the stars, who are dressed in their finest ghetto chic. ‘Whatever continent you’re on, the cool kids have the Urban look,’ Urban video clip director Hype Williams has remarked. The lively urban space evoked among the products and activities associated with the Urban youth culture may be termed intermedial. The intermedial spatiality of the city is no longer stuck to a physical environment or a social process. The form of the city is no longer determined by the pattern of ownership boundaries, but by the medial diversity that makes it urban. In this way, the city can dissolve into an audiovisual meaning-sphere which is continually actualized in combination with various products and activities. Identity is then no longer a fixed or static datum, but is something that forms between media and pop culture.

Unified Context

People build spheres. Does that mean that the city is moving into a phase where urbanity no longer needs any geographical specificity or compelling architecture? It is becoming ever clearer that in time everything turns into a city. Like an autonomous force, it seems to spread in all directions. But the process of urbanization which is so closely associated with that force is not definable only geographically, even though the expansion of the physical space of the city, when expressed in figures, is impressive. Other processes too form part of the urbanization. Consequently the intermedial urban space that ‘Urban’ creates by bringing the city into connection with a motley mass of products and activities is all the more striking. We could justifiably argue that changes of this kind should be considered as part of the process of urbanization. What new urban spatiality develops as a result? What has changed there? To sum up, we may hold that the process of urbanization disintegrates into various processes. Besides changing our physical space, social changes also engender a new social space and the rise of an intermedial space.23 To fully understand the urbanization process, we have no choice but to view these spatialities in a unified context.

An extended version of this article will appear in the authors’ book Mediapolis, to be published in 2006 by 010 Publishers (see www.studiopopcorn.com).

Literature

- M. Cobussen, ‘De terreur van het oog’, De Groene Amsterdammer, 10 January 1996.

- M. Cobussen, ‘Verkenningen van / in een muzikale ruimte. Over Peter Sloterdijk en Edwin van der Heide’, in H. A.F. Oosterling and S. Thissen, Interakta#5, Grootstedelijke reflecties. Over kunst en openbare ruimte (Rotterdam: Faculty of Philosphy of Erasmus University, 2002).

- P. Cook, Archigram, (London: Studio Vista Publishers, 1972). J. Cronly-Dillon, K.C. Persaud, ‘Blind Subjects Analyze Visual Images Encoded in Sound’, Journal of Physiology 523P, 68, 2000.

- G. Deleuze and F. Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987).

- K. Eshun, More Brilliant Than the Sun. Adventures in Sonic Fiction (London: Quartet Books, 1998).

- M. McLuhan and B.R. Powers, The Global Village. Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- A. Mulder, Over Mediatheorie (Rotterdam: V2_ / NAi Publishers, 2004).

- A. Ogg, The Men behind Def Jam. The Radical Rise of Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin, (London: Omnibus Press, 2002).

- H. Oosterling, ‘Intermediality. Art between Images, Words, and Actions’, in B. Marì and J.M. Schaeffer (eds.), Think Art. Theory and Practice in the Arts of Today (Rotterdam: Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art, 1998).

- H. Oosterling, Radicale middelmatigheid (Amsterdam: Boom, 2000).

- S. Reynolds, Energy Flash. A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture (London: Picador, 1998).

- A. Rossi, The Architecture of the City (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1999).

- R.M. Schafer, The Soundscape. Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (New York: Knopf, 1977).

- P. Shapiro, (ed.), Modulations. A History of Electronic Music (New York: Caipirinha Productions, 2000).

- M. Schuilenburg and A. de Jong, ‘De militarisering van de openbare ruimte. Over de invloed van videogames op onze werkelijkheid’, in Justitiële verkenningen, no. 4 (The Hague: Boom Juridische uitgevers, 2005).

- P. Sloterdijk, In hetzelfde schuitje: proeve van een hyperpolitiek (Im selben Boot. Versuch über die Hyperpolitik) (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 1997).

- P. Sloterdijk, Mediatijd (Amsterdam: Boom, 1999). P. Sloterdijk, Sferen (Sphären I, II) (Amsterdam: Boom, 2003).

- M. Sorkin, ‘Amazing Archigram’, in Metropolis Magazine (New York, 1998). A. Toffler, The Third Wave (New York: Bantam Books, 1980). Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, Stad en land in een nieuwe geografie. Maatschappelijke veranderingen en ruimtelijke dynamiek (The Hague: Sdu Uitgevers, 2002).

1. Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, Stad en land in een nieuwe geografie. Maatschappelijke veranderingen en ruimtelijke dynamiek (The Hague: Sdu Uitgevers, 2002), 89.

2. Peter Sloterdijk, Mediatijd (Amsterdam: Boom, 1999), 79.

3. The group became known under the name Archigram through action of the English architectural critic Reyner Banham. Originally, Archigram was the title of the manifesto. Until the end of the 1960s, the architects who came to form the Archigram group worked independently in various architecture firms and educational institutions. It was not until 1969, when they won a competition for the design of an entertainment centre in Monaco, that practical considerations led them to set up an architecture office together. Prior to that, their goal was different: to throw a spanner in the works of the architectural discourse by introducing a coherent alternative world.

4. ‘Bucky’ Fuller devised the Dymaxion House in 1927. This was a hexagonal metal cell suspended around a central vertical axis like a horizontal bicycle wheel. The house could be built like cars in a factory and placed wherever required.

5. Peter Cook, Archigram, Studio (London: Vista Publishers, 1972).

6. Sloterdijk, Mediatijd, op. cit., 94.

7. Ibid.

8. Peter Sloterdijk, In hetzelfde schuitje: Proeve van een hyperpolitiek (Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 1997), 39.

9. Cities have a long history of electronic dance music. Besides techno in Detroit, house music arose in Chicago clubs like The Warehouse, The Music Box and The Power Plant. Ten years later, jungle was to be heard on the London airwaves from pirate radio stations like Kool FM, Pulse and Defection, while Paul Elstak and Speedy J surprised Rotterdam with the frenetic beat of gabber. All these music styles have succeeded in making their home cities a subject of interest again. While Juan Atkins and Rick Davis declared Detroit ‘Techno City’, Paul Estak, operating under the name Euromasters, put Rotterdam on the map in 1991 by releasing the gabber number Amsterdam, waar lech dat dan? as the first record bearing his label Rotterdam Records.

10. See also M. Cobussen, ‘De terreur van het oog’, De Groene Amsterdammer, 10 January 1996.

11. See also M. Cobussen, ‘Verkenningen van / in een muzikale ruimte. Over Peter Sloterdijk en Edwin van der Heide’, in: H.A.F. Oosterling and S. Thissen (eds.), Interakta #5, Grootstedelijke reflecties. Over kunst en openbare ruimte (Rotterdam: Faculty of Philosophy, Erasmus University, 2002).

12. Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, Stad en land in een nieuwe geografie, op. cit., 137.

13. It must not be forgotten that the power of sound is also its greatest threat. The strength of sound is more intensive than that of other experiences. It is collective in nature. That, according to Deleuze and Guattari, is where the fascist peril of music lies. In A Thousand Plateaus (1980), they suggest that drums and trumpets, much more than the visual violence of banners and flags, can tempt people and armies into a race into the abyss: ‘Colours do not move people. Flags can do nothing without trumpets.’ A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 348.

14. S. Reynolds, Energy Flash. A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture (London: Picador, 1998), 9.

15. Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, Stad en land in een nieuwe geografie, op. cit., 137.

16. In his article ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’ (1953), the Situationist Gilles Ivain sketched a city with districts corresponding to the entire spectrum of sensations and emotions: the bizarre district, the happy district, the noble and tragic district, the historic district, the useful district, the ominous district and the death district.

17. See also Siebe Thissen, ‘Wat is Urban Culture? (My Adidas)’ (2004 / 2005) (www.siebethissen.net).

18. Besides urbanus, the word Urban is connected with the word urbs, meaning ‘big city’. Urbs has the same root as orbis which can mean sphere or ring. This suggests that the urbs is originally a city encircled by walls.

19. A. Ogg, The Men Behind Def Jam, the Radical Rise of Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin (London: Omnibus Press, 2002), 4.

21. The TV programme has been running for thirty years, is carried by 219 different American channels and reaches an average of 8.2 million viewers per transmission.

20. Ibid, 19.

22. Although Aldo Rossi argues in his study The Architecture of the City that ‘through architecture perhaps more than any other point of view one can arrive at a comprehensive vision of the city and an understanding of its structure’, Urban culture shows that the city can also be analysed in terms of other ‘fixed’ forms. Rossi’s view that the knowledge for future designs is implicit in existing buildings that have proved their worth over the ages must therefore be considered too restrictive.

23. It goes almost without saying that other spatialities can be distinguished besides social and intermedial space. The most important example is the virtual space of video games, where the action takes place more and more often in a city-like context. Since this essay centres on matters of sound, however, we opted not to explore this spatiality further here. The infiltration of virtual space into the physical space of the city is explored in an article about the militarization of public space due to video games by M. Schuilenburg and A. de Jong, ‘De militarisering van de openbare ruimte. Over de invloed van videogames op onze werkelijkheid’, Justitië le verkenningen, no. 4 (The Hague: Boom Juridische uitgevers, 2005).

Alex de Jong (the Netherlands) is an architect. He works for the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). He conducts research into the effects of urban processes together with Marc Schuilenburg under the name ‘Studio Popcorn’. A full version of this article will be included in their book Mediapolis, set to be published by 010 Publishers in 2006 (see www.studiopopcorn.com).

Marc Schuilenburg teaches in the department of Criminal Law and Criminology, VU University Amsterdam. His latest book The Securitization of Society: Crime, Risk, and Social Order (2015) was awarded the triennial Willem Nagel Prize by the Dutch Society of Criminology. See further: www.marcschuilenburg.nl.