The Fight over Transparency

From a Hierarchical to a Horizontal Organization

November 18, 2011essay,

Media theorist Felix Stalder describes the changed agenda of transparency in today’s neoliberal era. That agenda’s regime of measurability and standardization leads people to make forced choices in order not to be isolated or excluded. In order to avoid this, a new form of transparency is necessary, one that is horizontally organized and employs the newest means of communication.

Two radically different transparency paradigms are operating simultaneously. Within liberal political theory, the demand for transparency is directed at state institutions to create accountability to the public, that is to say the citizens from whom they derive their legitimacy. Within neoliberal political theory, the demand for transparency is directed at market participants to reduce uncertainty within a globalized sphere of action and abstraction. On the one hand, there is the question of how old notions of transparency can be made to function again within the context of a complex information society. WikiLeaks is currently the most effective actor in this debate. On the other hand, as market logic has expanded across nearly all domains of life and turns increasingly repressive as the economic crisis evolves, a different critique of transparency has been formulated, emphasizing subversive strategies of intransparency and a refusal to become visible and accessible. To understand the political dynamics of transparency more comprehensively – as both empowerment and control – we must look at all forms of transparency in terms of the social relationships they produce.

Accountability

Transparency – the accessibility of records of the internal processes of public institutions to third parties – is a key element of the functioning of the institutional system of checks and balances. One branch of government can meaningfully control the other and a flourishing public sphere can be created, so that elected officials (and the civil servants they oversee) can be held to account by their constituencies. For Max Weber, one of the defining characteristic of modern ‘legal authority’ is that ‘acts, decisions, and rules are formulated and recorded in writing, even in cases where oral discussion is the rule or is even mandatory [in court, for instance]. This applies at least to preliminary discussions and proposals, to final decisions, and to all sorts of orders and rules’.1 How many of these records are actually publicly accessible and hence really contribute to transparency through the public sphere is of course a matter of contestation and varies according to the balance of power imbedded in state institutions. Roughly speaking, however, through mechanisms such as Freedom of Information (FOI) legislation, which gives citizens the right to demand the release of records, the basic model established in the nineteenth century – requiring public institutions to record their actions and to grant access to these records – has steadily been expanded in Western countries. At the same time, there is a growing perception that many public institutions have nevertheless become less transparent and that the gulf between the state and its citizens has widened. Democracy is slipping into a veritable crisis of legitimacy.2 In part, this crisis stems from the inadequacy of the means that are supposed to create transparency. There are structural and political reasons for this. First, getting access to the records is cumbersome. For example, submitting a Freedom of Information request can be very complicated, and the response subsequently takes months. In the end, moreover, any request can be denied for opaque reasons. Second, the complexity of government and the mass of records have grown so much that it is increasingly difficult to determine in advance which individual records are relevant and thus warrant a FOI request. Often, what provides genuine insight is not an individual record, but a large body of records viewed together. Yet the format of the records (often paper records, or if electronic, handed over as printouts) makes it very difficult to process them in the quantities required to understand complex procedures. There is also a subjective aspect to this. In an age in which we have grown accustomed to instant access to masses of information through sophisticated infrastructures, the slowness and complexity of these official processes seem like acts of obstruction. There is, in other words, a mismatch between the means available in practice and the ends these means should achieve in theory, even if the system were to work without obstruction within its current design. But it does not, since there is also a political side to the problem. Public officials have found it convenient to shield more and more of their activities from public scrutiny – particularly those they fear will generate critical reactions from the public. They do so by invoking the catch-all spectre of national security, by interpreting notions of ‘executive privilege’ very broadly, or simply by adopting secrecy as a mode of operation, particularly in international negotiations. For instance, the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA), a controversial but by and large standard treaty, was negotiated in secret for two years before the existence of negotiations was even publicly confirmed. Even then, it took another two years and a massive public campaign before the near-final draft was officially released in April 2010. As Michael Geist concluded, ‘it represent[ed] a major shift toward greater secrecy … in an obvious attempt to avoid public participation and scrutiny.’3 The combined effect of these structural and political dynamics is that the state is seen as neither capable nor willing to provide transparency in a manner adequate to generating democratic debates about central aspects of its activities.

The Role of WikiLeaks

WikiLeaks aims to intervene on both levels. First by providing access to public records in ways that are adequate to the technological culture of the present. They are put online, made searchable and machine-readable, downloadable, and are available to anyone, for any purpose, without registration or other access controls. Second by providing access to records of public interest that have been shielded from the public, even in the face of explicit FOI requests. The case in point is the video of an Apache helicopter whose pilots shot a group of unarmed men, including journalists Saeed Chmagh and Namir Noor-Eldeen, in Baghdad on 12 July 2007. The journalists’ employer at the time, Reuters, immediately filed a FOI request for this video, but this request was repeatedly denied. On 5 April 2010, WikiLeaks released this video under the title Collateral Murder, in an edited and an unedited version. Once the video was released, it became clear that the FOI request had been denied primarily because the video was highly embarrassing to the US government.

Despite the controversy about and hostility against WikiLeaks stirred up by angry officials and envious media, as well as considerable tensions and contradictions inside the project itself,4 the public response to the releases has been overwhelmingly positive. Its editor in chief, Julian Assange, has become a global celebrity and a hero to many. WikiLeaks can rely on a widespread sentiment that public institutions are not transparent enough and that unconventional means of providing transparency are necessary. This sentiment was latent before WikiLeaks came into being, but the project has brought it to the fore and at the same time radicalized demand for new forms of transparency. While WikiLeaks itself is currently somewhat in limbo (it has not accepted new submissions since late 2010), the dynamics it accelerated are now propelling other initiatives forward. On the one hand, existing initiatives that seek to renew the official mechanisms for generating transparency have received a boost and new ones are springing up. For example, government open-data initiatives have been created all over the world over the last year or two. The idea here is that instead of granting access to individual (paper) records, governments should provide access to entire databases in open and machine-readable formats over the Internet, so that third parties can take and interpret this data in any way they see fit. There is now a serious debate on the type of databases that can or need to be made accessible in this way, and the technological standards that define how the data can accessed and used.

A number of new laws, either just passed or currently in preparation, aim to increase the transparency of politics, particularly in relation to the flow of money from lobbyists and the financing of political parties. On the other hand, heavy-handed attempts to cripple WikiLeaks by leaning on key providers of communications infrastructure – payment networks, cloud computing services or domain name registrars – have politicized and radicalized a new generation of hackers. These share none of the concerns of WikiLeaks about the ethics and responsibilities of independent publishing (however idiosyncratically WikiLeaks may have interpreted these in practice). Rather than wait for whistle-blowers, they break into systems to gather data, and rather than edit the material to protect individuals and provide context, they simply dump the raw material on the Internet. All of this has prompted a wide-ranging debate about the legitimacy of secrecy for public institutions and the need to find better ways of ensuring that transparency, in practical terms, can continue to fulfil its function within the liberal conception of the state.

Assumptions

This revival of the liberal notion of transparency warrants a revival of its critique. Henry Lefebvre’s analysis, formulated in the early 1970s, is now more relevant than ever: ‘The presumption [behind the demands for transparency] is that an encrypted reality becomes readily decipherable thanks to the intervention of first speech and then of writing … In any event, the spoken and written word are taken for (social) practices, it is assumed that absurdity and obscurity, which are treated as aspects of the same thing, may be dissipated without any corresponding disappearance of the ‘object’ … Such are the assumptions of an ideology which, in positing the transparency of space, identifies knowledge, information and communication. It was on the basis of this ideology that people believed for quite a time that revolutionary social change could be achieved by means of communication alone.’5

Underlying the ideology of transparency Lefebvre identified is the assumption that it is primarily the lack of communication and knowledge that prevents institutions from functioning properly, and, conversely, that more communication and more knowledge will, by themselves, correct this problem. This assumption was as problematic in 1974 as it is now. In Lefebvre’s view (and that of other Marxists), the main issue regarding the operations of state institutions was not their inefficiency, but the antagonistic social relationships they embodied. Making the state work more efficiently by increasing transparency would solve only the bourgeoisie’s problems. Radical politics, on the other hand, would have to change the social relationships embodied in and reproduced by the state. Current critics of open-data initiatives, few as they are, see related issues, although they follow an analysis of power more in line with Pierre Bourdieu’s. Michael Gurstein, for example, focuses on the cultural specificity of information released by open-data initiatives and the patterns of inclusion and exclusion they (re)produce. Analysing the transparency site for parliaments in the UK (TheyWorkForYou.com), one of the more prominent open-data projects to date, he concludes that ‘this attempt to enhance democratic participation has ended up providing an additional opportunity for those who … because of their income, education, and overall conventional characteristics of higher status (age, gender, etc.) already have the means to communicate with and influence politicians. The additional information and an additional communications channel thus [have] the effect of reinforcing patterns of opportunity that are already there rather than widening the base of participation and influence.’6

His critique serves as a warning against the assumed objectivity (aka ‘the data speaks for itself’) and capacity of transparency to bypass murky politics. He points out that the production of knowledge itself is already political, and that providing transparency is not the end, but just another step in the long march of politics.

Control

This part of the debate can be understood as an upgrading of the nineteenth-century transparency paradigm to the twenty-first century. In the meantime, however, a very different analysis of transparency has been proposed, most notably by the Tiqqun collective7 and by Brian Holmes.8 They take as their starting point cybernetic capitalism and neoliberalism, developed after the Second World War and having gained social dominance as the answer to the crisis of Keynesian industrial capitalism in the 1970s. In this process a very different notion of transparency was established. Instead of being concerned with the accountability of public institutions towards citizens, it was conceived as a way to reduce ‘information asymmetries’. Its main function, therefore, was to make markets work more efficiently. This concern with the role of information in the functioning of markets stems from the idea of markets as being composed of highly decentralized actors operating locally but coordinating across space with one another through the market.

This perspective was famously formulated by F.A. Hayek right at the end of the Second World War. For him, there are two types of information. One is the actor’s ‘limited but intimate knowledge of the facts of his immediate surroundings’; the other is provided by the ‘price system as … a system of telecommunications which enables individual producers to watch merely the movement of a few pointers, as an engineer might watch the hands of a few dials’.9 For this system to work properly, agents need as much information as possible about their ‘immediate surroundings’ and the price mechanism must not be distorted by regulatory interventions in the markets. To advance this vision in a globalizing world, two problems need to be addressed. One is that gaining knowledge of one’s ‘immediate surroundings’ becomes problematic, due to the loss of intimate connections to one’s physical surrounding through the destruction of local social bonds. At the same time, one’s ‘immediate’ surroundings have expanded to the point where they encompass the entire planet. This is yet another instance of Marshall McLuhan’s famous global village. The other problem is that for the markets to work in this fashion, they need to become integrated globally. In this perspective, national borders are viewed as market-distorting mechanisms.

One way of understanding globalization, therefore, is as a process of standardization10 aimed at addressing these two issues, which according to this theory prevent markets from functioning properly. The latter issue is addressed by the World Trade Organization (WTO) and various bilateral or multilateral free-trade agreements, the former through the development of diverse ‘transparency regimes’ defined as government mandates that require corporations or other organizations to provide the public with factual information about their products and practices. Disclosed information is structured for comparability and updated at regular intervals.11

Because of the fracturing of social space locally as well as the problem of global integration, transparency regimes have been implemented on every scale. A local example would be Los Angeles County’s restaurant grading system, adopted in 1997, which requires restaurants to prominently display the results of their most recent hygiene inspection, expressed in grades of A, B or C. Consumers can now see which establishments passed their most recent inspections and factor this into their purchase decisions. Global examples are equally ubiquitous, ranging from reporting requirements for publicly traded companies to the standardized statistical reporting of entire national economies. The increasing importance of institutions such as the International Standards Organization (ISO) and their expansion from the standardizing of objects to the standardizing of processes, quality management in particular (through the ISO 9000 standards), is a testament to this development.

The operative words here are expansion and standards. While the dream of cybernetics to create a new meta-science failed to materialize and lost its attraction in the 1960s, its fusion with free-market ideology proved very potent. Over the last 30 years, virtually every aspect of social life has been made measurable, standardized, comparable, and then linked to some form of financial marker, be it price, debt or a budget item. The whole of society has been made to function according to cybernetic market principles, and the process engineers of management can now monitor everything simply by tracking a few numbers.

Standardization Leads to Forced Choices

Creating transparency has been a crucial step in this process. If we recall the value that Hayek placed on the economic actor’s need for intimate knowledge of his ‘immediate surroundings’ and that the role of transparency is to increase that knowledge, it is hardly surprising that the social consequences of this evolution have been highly uneven. They favour those who can act most effectively through the market while subjecting everyone else to ever more stringent disciplinary regimes. That is the expansion part. Subjugation to this new regime has not been achieved through force, at least not primarily. It has been achieved through the establishment of particular standards capable of unleashing these dynamics.

A standard constitutes ‘the particular way in which a group of people is interconnected in a network. It is the shared norm or practice that enables network members to gain access to one another, facilitating their cooperation’.12 As such, standards seem rather innocent; indeed, they are indispensable in coordinating the interaction of formally independent agents. However, they set the rules by which these agents can interact. Once a standard has been established, it can constitute an ‘all-or-nothing’ proposition. The standard must be accepted in order to gain access to a particular network and the resources and opportunities present within it. If the standard is not accepted, there is no access. From the point of view of the outsider, adopting a particular standard can seem a forced choice, since the alternative would be social isolation; from the point of view of the network, standard acceptance is always voluntary.

The case in point is the WTO. It is the enforcer of the neoliberal empire on a global scale. Yet this is clearly not gunboat imperialism: the WTO is a voluntary organization to which nation-states have to apply for membership. The result is structural coercion under conditions of formal freedom.13 Entire states, organizations large and small, and individual people voluntarily submit to coercive regimes because these constitute the conditions under which they can gain access to particular resources and opportunities. No matter how rigged the game might be, in a networked age, isolation would almost always be worse. Think of applying for a grant for a cultural project or joining Facebook. You hate it, but you still agree to it, while pretending to like it.

Because there is (normally) no direct coercion forcing people into a particular standard, but rather individual voluntary decisions to adopt it, power is dispersed and difficult to localize. The appropriate way to confront this type of power is therefore not to attack the holders of power, but to challenge the particular standard through which it operates. Tiqqun, however, outlined a more radical approach. Instead of confronting a particular standard, it aims to subvert the underlying mode of operation of an entire class of standards – those identified as part of the cybernetic control regime. This underlying mode of operation is the creation of transparency. Consequently, Tiqqun developed a set of tactics to reduce transparency, thus undermining a key operating requirement for these standards. The key tactic proposed is to become invisible, to withdraw from the action (as a strategic retreat, not as an escapist fantasy) – to turn into fog: ‘Fog is a vital response to the imperative of clarity, transparency, which is the first imprint of imperial power on bodies. To become foglike means that I finally take up the part of the shadows that command me and prevent me from believing all the fictions of direct democracy insofar as they intend to ritualize the transparency of each person in their own interests, and of all persons in the interests of all. To become opaque like fog means recognizing that we don’t represent anything, that we aren’t identifiable; it means taking on the untotalizable character of the physical body as a political body; it means opening yourself up to still-unknown possibilities. It means resisting with all your power any struggle for recognition.’14

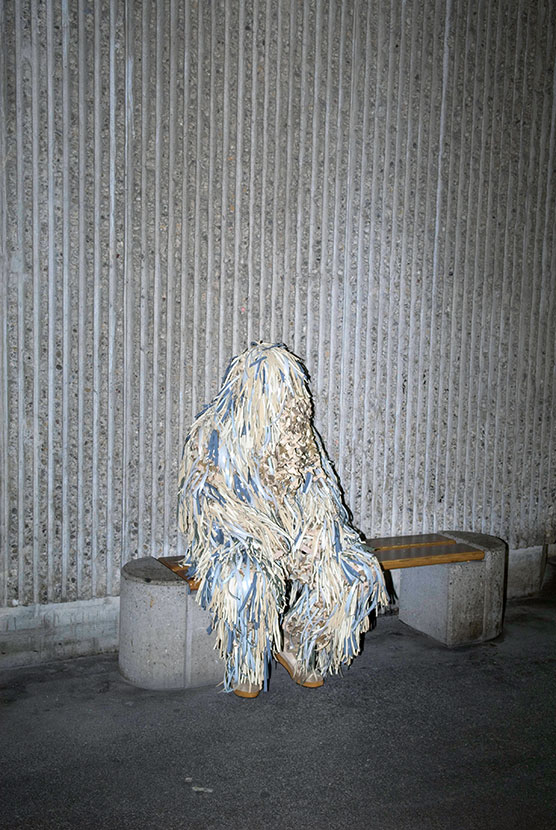

This approach has been enormously influential and particularly productive in the arts, where there has been a string of recent projects (like Andreas Broeckmann & Knowbotic Research’s 2010 Opaque Presence15 or Seth Price’s 2008 How to Disappear in America)16 and exhibitions (like HMKV’s ‘Gone to Croatan’, 2011)17 dealing with invisibility, disappearance and forms of withdrawal. This strong interest from artists is perhaps not surprising, as Tiqqun formulates not so much a political as an aesthetic strategy (fog, invisibility, opacity, rhythm, slowness, and so forth). In scale, the approach is individualisitic (even if Tiqqun speaks of small collectives) and in sentiment it is Romantic (reclaiming spontaneous life against the dead hand of control) making it well suited to artistic practices, but problematic for a wider politics.

Horizontally Organized Transparency

The inversion of the critique of transparency into a politics of invisibility leads to a dead end of romanticizing clandestine groups whose internal communications intensity must compensate for a lack of external connections. It ends up sacrificing the one key contemporary innovation that can make new forms of political agency possible: the ease with which new ‘weak’ connections can be generated through digital media, enabling the synchronization of independent agencies into a new collective rhythm. This synchronization is enabled through small acts of trust – which may lead to greater acts of trust further down the road – made possible through particular forms of visibility. People come to see one another and experience zones of mutuality (and zones of conflicts). For this, some sort of transparency is absolutely crucial. Without the recognition of a mutuality of affects, social solidarity cannot emerge. And without relatively open forms of transparency, mutuality cannot increase in scale, remaining locked in a fractured landscape of small communities that communicate with one another through clandestine channels invisible to outsiders. In other words, intensity is no substitute for scale.

We must differentiate between different modes of transparency and the social relationships they enable. Transparency within the liberal conception, in its nineteenth- and twenty-first-century forms, takes the existence of hierarchical state institutions and of power through representation as a given, but aims to balance it with what one might call ‘bottom-up’ visibility. Because it recognizes that the state is based on a design in which institutions concentrate power, it needs mechanisms to hold those inside these institutions – that is, those who hold power – accountable to those outside whom they are supposed to serve These relationships of accountability should not be casually dismissed, but they no longer suffice, because power no longer operates merely through institutions but increasingly through standards. These currently dominant standards demand particular forms of transparency that, in effect, create a kind of ‘top-down’ visibility, whereby those with substantial information-processing capacities can adjust, more or less subtly and to their own benefit, the conditions under which all others operate as ‘free agents’. Rather than work through commands, power operates through the seemingly neutral formulation of ‘if … then’ propositions. The transparency of the social body ensures that these propositions are subtle enough to be read as statements of facts, rather than as acts of coercion.

If we accept that standards are ways to enable the social coordination of autonomous agents (that is, those outside hierarchical command-and-obey structures) we need to develop different standards that are not infused by the neoliberal programme. If we accept that contemporary sociality needs to operate on a global scale, we need to find ways of articulating mutuality on that scale. A precondition of this is a form of visibility that allows for the synchronization of actions without feeding the machine of cybernetic control. Thus, we need a paradigm of transparency that is strictly horizontal, that enables us to extend sociality to a very large scale. This requires new standards of communication, new tools of communication that actively support the experience of mutuality and actively prevent the implementation of top-down visibility.

1. Max Weber, Economy and Society (1922), translated by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich (New York: Bedminster Press, 1968), 219.

2. Colin Crouch, Post-Democracy (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004).

3. Michael Geist, ‘ACTA Guide, Part Three: Transparency and ACTA Secrecy’, Michael Geist’s Blog (michaelgeist.ca), 27 January 2010: www.michaelgeist.ca (last accessed on 15 July 2011).

4. Daniel Domscheit-Berg, Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World’s Most Dangerous Website (New York: Random House, 2011).

5. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (1974), translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991), 28–29.

6. Michael Gurstein, ‘Are the Open Data Warriors Fighting for Robin Hood or the Sheriff?: Some Reflections on OKCon 2011 and the Emerging Data Divide’, Gurstein’s Community Informatics (gurstein.wordpress.com), 3 July 2011: www.wp.me (last accessed on 15 July 2011).

7. Tiqqun, ‘The Cybernetic Hypothesis’, Tiqqun no. 2, 2001, English translation posted on cybernet.jottit.com in 2009 (last accessed on 15 July 2011). (See also: www.theanarchistlibrary.org).

8. Brian Holmes, ‘Future Map’, Continental Drift (brianholmes.wordpress.com), 9 September 2007: brianholmes.wordpress.com.

9. Friedrich A. Hayek, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society’, American Economic Review, vol. 35, no. 4 (September 1945), 519–530.

10. David Singh Grewal, Network Power: The Social Dynamics of Globalization (New Haven / London: Yale University Press, 2008).

11. Archon Fung, Mary Graham, David Weil and Elena Fagotto, The Political Economy of Transparency: What Makes Disclosure Policies Effective? (December 2004), research paper available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): www.ssrn.com (last accessed on 15 July 2011).

12. Grewal, Network Power, op. cit. (note 10), 21.

13. See ibid.

14. Tiqqun, ‘The Cybernetic Hypothesis’, op. cit. (note 7).

15. Andreas Broeckmann and Knowbotic Research (eds.), Opaque Presence: Manual of Latent Invisibilities (Berlin / Zurich: Diaphanes / Éditions Jardins des Pilotes, 2010).

16. Seth Price, How to Disappear in America (New York: The Leopard Press, 2008).

17. ‘Gone to Croatan – Strategien des Verschwindens’, group exibition by Hartware Medienkunstverein (HMKV), Dortmunder U, Dortmund, Germany, 4 June–14 August 2011.

Felix Stalder is a professor of digital culture and network theories at the Zurich University of the Arts and an independent researcher / organizer working with groups such as the Institute for New Cultural Technologies (t0) in Vienna. His research interests include: Free and Open Source Software, Free Culture, emancipatory cultural practices, theories of networks and the network society, of digital culture, of the transformation of space and its practices, as well as theories of subjectivity. His publications are available at www.felix.openflows.com.