The Politics of Colours

April 13, 2005review,

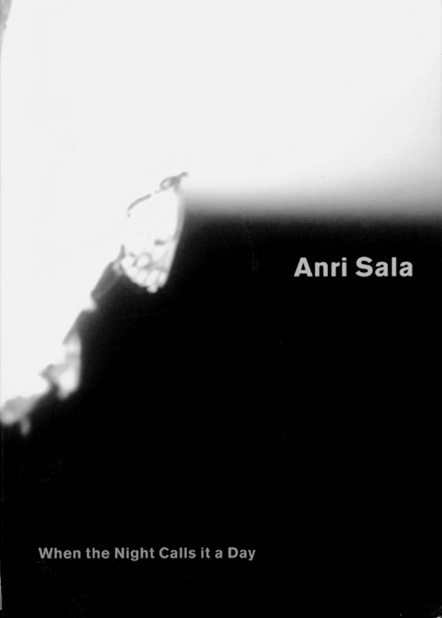

Anri Sala, Entre chien et loup / When the Night Calls it a Day / Wo sich Fuchs und Hase gute Nacht sagen, Deichtorhallen Hamburg and Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris / ARC (eds). Walther König Publishing, Cologne 2004. English / German edition ISBN 3883758086, English / French edition ISBN 388375806X

There was one work which stood head and shoulders above the rest at ‘Utopia Station’, the disorderly tailpiece of the most recent Venice Biennale. It was a film, which showed a strange and wonderful journey through the night and day of a dilapidated Eastern European city with a man in a taxi – Mafia boss or artist? – who offers a detailed account in an incomprehensible language to someone who remains out of shot. Buildings and streets are reduced to rubble, broken-down means of transport edge their way through, stray dogs appear and disappear, little huddles of people stand around fires. So far the film is showing the clichéd image of a city in a former war or disaster area, with one crazy difference: the facades of the houses are painted in vibrant ‘colour fields’. Is this the work of a house painter on the loose? Is it the result of a ‘percentage for art’ programme that has spun out of control? I didn’t have a clue, because as usual at such exhibitions there was little background information and the subtitling wasn’t functioning – on that day at least – so with affection and bemusement I stored away this short film on my hard disk.

Titled Dammi i colori (‘Give Me Colour’), the creator of this work was Anri Sala, an Albanian artist in his thirties who has already produced a sizeable oeuvre. Eight of his projects from 2001 to 2004 are described in detail in the publication: Entre chien et loup / When the Night Calls it a Day / Wo sich Fuchs und Hase gute Nacht sagen, beautiful expressions for what is also known as twilight. This is the time when the day transforms into night, and time and space briefly seem to dissolve: an in-between time that is typical for Sala. At this time, our imagination goes into overdrive and we confuse a dog for a wolf.

In the catalogue for the 2003 exhibition ‘In den Schluchten des Balkan’ (‘In the Gorges of the Balkans’), the Albanian curator Edi Muka brands Balkan artists like Sala the ‘new proletarians of the art world’, artists who still have nothing to lose and are not yet shackled by the international art scene. That Sala is the exception to the rule is demonstrated by the list of internationally renowned gallery owners, his biography, and the impressive line-up of writers in the book that appeared to accompany his exhibitions in Hamburg and Paris. Published in both English / German and English / French editions, besides texts by the exhibition’s three (!) curators, namely Laurence Bossé, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Julia Garimoth, the catalogue also includes essays by a number of eminent professors in the fields of philosophy, memory and psychology, and art history, such as Jacques Rancière and Israel Rosenfield. Sala’s rising star in the constellation of international art is ratified by the scenario for a film, which the star artist Philippe Parreno wrote for Sala. Parreno, who claims never to have seen a work by Sala and intends to keep it that way for the time being, has created a scenario for a mini-feature film based on conversations with Sala, a film that Sala might make in 2010. Parreno, who became known with Pierre Huyghe with the launch of the virtual character Annlee, who everyone could fill out artistically, totally misses the point with this scenario. Sala is obviously not a ‘shell figure’ like Annlee, though his work does invite a whole range of interpretations.

Molly Nesbit, co-curator of ‘Utopia Station’, for example, unquestioningly accepts the story by the mayor of Tirana, Edi Rama, formerly a painter, who has decorated the facades with a patchwork of colours at a furious tempo in anticipation of future (infra-) structural improvements to the city. By way of Wittgenstein, Nesbit becomes engrossed in the limitations of the knowledge of consciousness on the basis of colour (does your red mean the same as my red?) to conclude that colour in Tirana is ‘real’, and that aesthetics can again become politics. Nesbit puts forward the fact that the mayor has not exploited Sala’s film Dammi i colori, the film that was shown at the Venice Biennale, to promote Tirana as evidence of his sincerity.

A more interesting and more controversial interpretation of the same work is provided by the two young French philosophers, Alexandre and Daniel Costanzo, in their essay ‘The Politics of Colours’. They prick the mayor’s Utopian coloured bubble in the opening paragraph, then they analyse the fables of the city, the colours, politics and ‘cinematographic’ fiction. To begin with the latter, they make a distinction between film as a traditional political dream factory and film as a narrative machine, which are brought together in Sala’s film. Mayor Rama talks enthusiastically about the creation of a new society in which people form a close-knit community. But Alexandre and Costanzo note that Sala only allows the mayor to have his say; the city’s inhabitants have none. How democratic is a mayor who single-handedly decides the appearance of an entire city, and only then gauges the opinion of its inhabitants? And how does this stand in relation to the socialist and/or totalitarian belief in the engineerable society that has now been declared bankrupt? And if the colours project is a re-conquering of the public space over the space claimed by individuals, then what does that public space signify? Is it not in fact a feature of democracy to allow unplanned spaces which can be claimed by residents?

The designation ‘new proletarian’ turns out to be not wholly incorrect for Sala, if you bear in mind that he retains an old-fashioned belief in the power of art, while simultaneously maintaining an instinctive awareness of the powerlessness of the artist to bring about real changes. Sala’s work is politically engaged, without remaining stuck in the pamphlet-focused stance of much of the other art that was shown at ‘Utopia Station’. The clever thing with Sala’s methodology is that he creates space to prompt questions about the reality of the filmed images using cinematographic and artistic means. This results in strangely beautiful and moving works, which echo in your mind for a long time. The publication is justifiably conceived as a polyphonic commentary on the work of a multifaceted artist.

Brigitte van der Sande is an art historian, independent curator and advisor in the Netherlands. In the nineties Van der Sande started a continuing research into the representation of war in art, resulting in exhibitions like Soft Target. War as a Daily, First-Hand Reality in 2005 as BAK, basis voor actuele kunst in Utrecht and War Zone Amsterdam (2007–2009), as well as many lectures, workshops and essays on the subject within the Netherlands and abroad. In 2013–2014 she curated See You in The Hague at Stroom Den Haag, and co-curated The Last Image, an online archive on the role of informal media on the public image of death for Funeral Museum Tot Zover in Amsterdam. Van der Sande is currently working on a concept for a festival of non-western science fiction, that will take place in 2016.