The Post-Monumental Image

On Enduring Visibility in the Network Society

April 13, 2005essay,

In the last several years, under the spotlight of media attention, a number of spontaneous monuments have popped up all over the place, monuments that threaten to ignore society’s complexity and remain visible only as long as the media’s attention lasts. This places the traditional monument, as well as the collective memory, in jeopardy. In Jouke Kleerebezem’s view, the networked media and the network culture related to it, offer significant perspectives of a new process of ‘post-monumental conceptualization’, a new economy of attention.

There is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument. They are no doubt erected to be seen – indeed, to attract attention. But at the same time they are impregnated with something that repels attention. Like a drop of water on an oilskin, attention runs down them without stopping for a moment.

―Robert Musil1

Nations write history by commemorating their national successes and catastrophes and giving them a permanent place. Traditionally, monuments are often erected under the auspices of governmental entities. The traditional, historical monument that Robert Musil was writing of in 1936 thus constructs a collective memory by immortalizing persons or events of extraordinary importance. In this way, political interests remain visible within the most specific ramifications of the social enterprise – for those who recognize this.

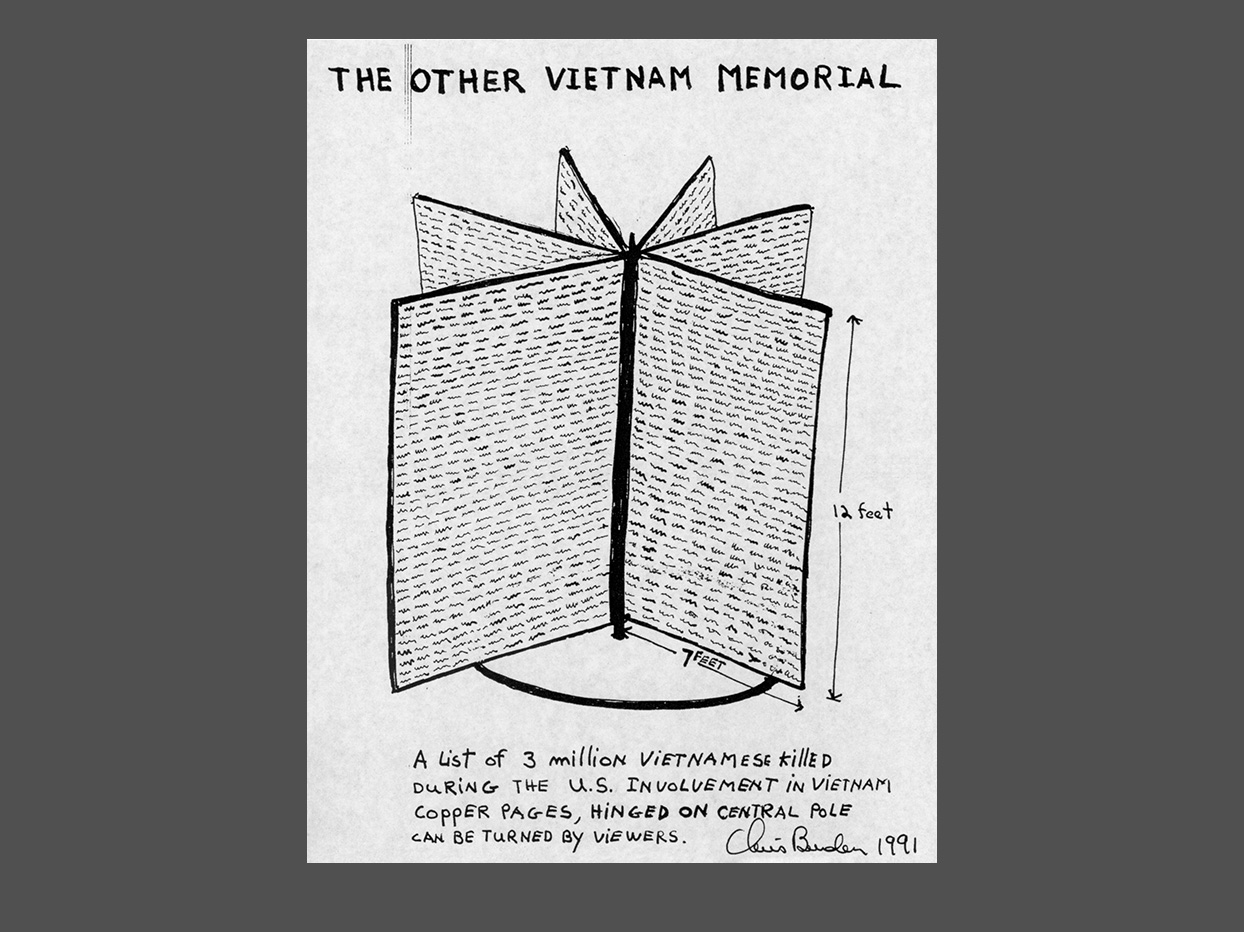

Monuments are often designed by artists. This does not, however, automatically mean that monuments belong to the domain of visual art. Within the oeuvre of its maker, the monument occupies a separate place, and it is seldom compared with other public or museum work. The artist Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, also designed houses, gardens, public art, a library, a museum, a line of furniture, a skating rink, clothing, two chapels, a bakery and autonomous installations. ‘I have fought very, very hard to get past being known as the Monument Maker.’2 The Other Vietnam Memorial, a work by Chris Burden that commemorates 3,000,000 Vietnamese dead, may have been conceived, in a critical sense, as a monument, but in essence it is a traditional post-conceptual museum artwork. A computer generated the names based on random names in four different Vietnamese telephone books.3 Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial names 57,661 actual victims.

The way the monument relates to art in public space or to museum art forms is not, however, the subject of this text. Instead the focus will be primarily on ‘new monuments’ created under the current political and cultural circumstances, on monuments that claim legitimacy outside the realm of traditional monuments as well as outside the realm of visual art. These new monuments attract a great deal of attention – especially in the media – for a short time, and in that sense they have the opposite effect to that of Musil’s monument. They are attention magnets instead of attention deflectors. They herald a post-monumental age, in which our attention is focused in a radically different way.

Media Monuments

The organization of visual art in public space follows the representative principle of the political structure. The patron – certainly in the Netherlands, where this form of art is significantly stimulated by the government – is keen to see the government’s interests made visible in the work, not only from a socio-political viewpoint but also from a symbolic perspective. You could call it state art by extension. The national memory is informed with images that are created thanks to the intervention of expert, democratically constituted commissions and with the assistance of funding institutions. In this process, experts with no direct political interests make government policy and allocate collective funding, so that art in the public domain and art that does not thrive in the commercial circuit can be produced. Subsidies presume to correct a market, but they have become the market: a discrete economic reality. Outside the art trade and the subsidy market, attention seems to be increasingly focused on a new type of monument. The breakdown of a government monopoly on the establishment of monuments creates a space in the public domain for a wide variety of spontaneous memorials not initiated by official authority.

In public space as well as in the media, initiatives are taken to write not so much history as current events. Even in their democratic aspects, some of these projects can be unmasked as stubborn attempts to salvage what remains of established representative interests. The public broadcasting service originally founded as the Catholic Radio Broadcasting Organization, the organ for Catholics in the Netherlands which has for some time now, in order to update its own identity, been using the image of a breast-feeding Virgin Mary as its media banner, took the initiative of holding a competition to name the ‘Greatest Dutchman of All Time’.4 Pim Fortuyn and William of Orange, bien étonnés de se trouver ensemble, vied for the honour. Friends of Theo van Gogh championed the former; friends of the country’s history championed the latter. The audience of tv station Nederland 1 enjoyed the ‘Idols’-like proceedings and cast their votes. This was the way to create a media monument circa 2004. It lays no claim on prosperity, makes little lasting impression and is not relevant to national historiography. But it caught the public’s attention unlike any other cultural event.

Alongside these media-driven monuments, everyday monuments are popping up that do not tell of great events or great people. They are not established by official or expert institutions. The individual citizen creates his own memorial to a drug user unjustly suspected of theft, improvised on the spot where she was kicked to death by supermarket employees. Individual initiative assumes the responsibility of making the outrage visible in a modest monument. A broad community contributes by making a piece of public space available, possibly maintaining the memorial, deploying a handful of police officers at its unveiling by a city alderman salaried by collective funds.

Media attention, however short-lived, is often the only homage the average person can receive today. The attention fades as quickly as the flowers wilt and the tea-candles burn out at the scene of the crime. In the mass media, brief over-exposure is followed by enduring invisibility. Just as media images begin to actually interest us in particular events and persons, they vanish from television screens and the pages of magazines and newspapers, to pop up again goodness knows when – if they ever do.

The End of History

We live in a time when official institutions and traditional monuments have little or no meaning anymore and the dominant conceptualization of societal ideas and processes has come to an end. This so-called ‘end of history’ coincided with the rise of the mass media. It was the end of a monopoly on history in which only a select few sources were tapped in order to make the world visible. But the more sources emerge, the less authority the proffered images exude.

Traditional monuments, which are articulated in regularly recurring manifestations, have a prominent claim on visibility. We see, however, that they cannot hold attention. Could a more enduring appeal for visibility grow out of the defenceless memorial? A memorial for passers-by, who pause to reflect at their own initiative, to burn a candle, for instance; a monument that is just as modestly commonplace as the event that inspired it? Might such a ‘defenceless’ monument be able to hold our attention after all? Would it not, in Musil’s words, be ‘impregnated’ to repel attention, as in the traditional monument?

Did the reason lie in the monumental authority that the multi-faceted meanings of great events and historical figures attempted to set down in an authoritarian conceptualization? Was it precisely the claim on the extraordinary, on special historical circumstance, that was the major component of this ‘impregnation’? Is not everyday life more memorable than the monument – more so than art, even, truth stranger than fiction? And should that everyday life be commemorated, articulated, made special in monuments – however democratic and short-lived? Are other kinds of symbolic and perhaps practical memorials imaginable, which can better focus our ordinary, special interests and fix them more lastingly in our memory?

A belief in the value and the power of the ordinary seems to contradict the importance we attach to art. After all, we expect art to make our perceptions and experiences special and elevate them above the anecdote. The ordinary monuments against random violence and the temporary homage to public ‘figures’ who become victims of murder or accident make visible a great sorrow and a great anger. The new monuments, like the new political engagement, are above all demonstrative. These new monuments are protest monuments. They do not merely commemorate the special qualities of the memorialized person but above all protest the lack of extraordinary qualities in the representatives of an established system and their preoccupation with the mass media. If the new monuments make anything visible, it is the anger at an established order unable to be credible and trustworthy, no matter how it tries to present itself as ordinary. In that sense they are of historic significance.

History, tradition, politics, art and the monument labour under the studio lights to create a popular conceptualization that tries in vain to become monumental according to historical examples. It tries to hold the public’s attention and stamp itself in the collective memory. But media visibility does not produce enduring images. These media monuments seem ‘impregnated’ against complex meanings, associations and reflection. They merely attract our attention for a moment, only to distract it as quickly as possible and focus it on the next insubstantial event.

This is of course more applicable to the competition for the ‘Greatest Dutchman of All Time’ than to the word ‘HELP’ hung in neon in the Voetboogsteeg in Amsterdam as a remembrance of Joes Kloppenburg’s murder. The more superlatives accompany the presentation, the more short-winded its advocates are, the more short-lived the excitement and the briefer the memory. The Greatest Dutchman of All Time will always be a media monument. It produces ahistorical, post-monumental, ex- tremely visible but very short-lived, commonplace protest entertainment. The temporary memorials on the site of a random crime, on the contrary, attest not only to impotent sorrow and anger, but to a protest against a media industry that offers no lasting narrative and seems primarily intent on making us forget.

Enduring Images

It is the task of art to consider and visualize our experience of current events and reintroduce this into societal reality, without immediately dissolving in commonplace mediality. It must nourish memory with reflection. This contributes to the value of art as knowledge and enduring insight into the way in which we identify, organize and enjoy matters of philosophy and entertainment. Art produces images that make an impact, that endure. These can be images varying from the most ephemeral to the most monumental forms, from the most conceptual to the most expressive expression. But ‘images that endure’ are not monuments; ‘making an impact’ is not the same as commemorating.

The extent to which contact with art contributes to the accumulation of knowledge and insight depends on complex factors that are difficult to generalize. In a time in which our ‘knowledge of knowledge’ is increasingly beyond the reach of institutionalization, it is all the more imperative that we subject the organization and expression of individual and collective memory to closer examination. The way in which we deal with current events and history is determined to a large degree by the mass media. It is precisely here that the epistemological crisis that the traditional culture and political system are undergoing becomes visible. Our knowledge of knowledge is being thrown out of balance by mediatization and informatization. Governments and social institutions no longer have any idea how a society should remember itself, or how it should know itself. They leave it up to the consumer. This lack of insight into the basic requirements of a mediatizing and informatizing society among the parties that formerly wielded authority creates curious mood swings from euphoria to mistrust. ‘Society’s shot to hell, but I’m doing all right’ was the predominant sentiment among Dutch people in a recent survey about the quality of life.

Mediatization

Investment in knowledge, in enduring principles and in images that can attract our attention every time, is taking place under the influence of two great communication projects. The first is mediatization, in which traditional ideas about collectivity and identity invite an incessant mobilization of as large an audience as possible. The second is informatization, in which the fragmentation of collectivity and identity into infinite sub-interests leads to new forms of interest promotion and social interaction. The difference between mediatization and informatization is not one separating different technological media. It is not a conflict between old and new media, or between analogous and digital production processes. We can observe the result of the mediatization process most clearly in the popular press and on television. The mass media seem to constitute a last social ‘institution’ that can be understood in traditional terms. However, they do not exhibit the principle of solidarity based on an ideological canon that characterized traditional organizations and movements: we do not become members in them. Therefore we would do better to consider the popular media as an aggregate rather than as a directional force, as a medium, a vehicle that holds disparate elements in a loosely relational context.

But the most significant aspect of mediatization is of course the endless expansion of the public realm, for the preservation of the media’s own industry. What is private is dramatized and what is public is individualized. Both in entertainment and in ‘more serious’ genres, television is the quintessential mass medium, with ‘content’ for and by a mass audience. On what is still the most popular medium, mediatization brings everything to our attention, without distinction as to the person, without distinction as to the quality of the content, without distinction as to the value of the exhibited knowledge, and without a response from the viewer, who is increasingly thematized and presented as part of the offerings, in the dramatic banality of his or her everyday existence.

Informatization

Informatization is a substantially different project, although, due to technological and commercial developments, parallels can be drawn with mediatization. Informatization outstrips mediatization in terms of technology and logistics at almost every level. The best model for studying informatization is of course the Internet. It provides an unlimited supply of content and offers the consumer superior selection and navigation possibilities. ‘Network culture’ – if we define it as the culture that could only emerge with the advent of the Internet – is characterized by the free exchange of digitized content among individual interested parties, independent of institutional intermediaries. The Net forms a platform in which every individual interest can be assured of a response and in which, thanks to the idealism of the first and second generation of Internet pioneers, an unparalleled amount and quality of cultural property is made available, free of charge. On the other hand, because it was dependent on wiring for the last 40 years, the Internet was long unable to penetrate society to the same degree as printed media or television. Thanks to today’s high-speed Internet connections, this gap is rapidly being closed.

In order to avoid thinking of informatization as a primarily technological condition, we must concentrate on the characteristics in which it sets out its objectives, those that distinguish it from mediatization. Informatization is geared not to the masses but to the individual. The network offers its infinite possibilities for the individual to identify him or herself in terms of his or her interests and then to search for the desired information, or to be addressed according to his or her individual knowledge and interests. Unless he or she deliberately presents him or herself as a member of a specific interest group, the network user cannot be addressed as such by other users of the network. Informatization is also the lasting storage of ‘content’ – data on ideas, people, and issues in the form of image, text and sound – to be kept ready and delivered to any address, on demand and as desired. This requires no editorial intermediary; it suffices that the data I am looking for is stored at that moment in the network and earmarked in such a way as to be delivered at my request.

The information network can also mediate, however. In response to my request, data can be added to my ‘content’ by another network user. All transactions in the information network unfold thanks to an unlimited storage of data in endless configurations and thanks to selective access to these data. While it is often said that the network operates according to a process of ‘dis-intermediation’, the reality is that what is taking place is ‘pan-intermediation’.

Of course, the information network is not free of mediatization. There are attempts to control data management and articulation according to the model of the old media. Mediatization is presented as the activity of a social institution that supposedly can help us choose or (re-)discover our cultural identity. It will supposedly shield us from nefarious information, or prevent our own information leaking out to those who might abuse it. As in any snake-oil scheme, the profiteers will actually swindle us out of the very thing they pretend to be protecting us from losing, namely our exclusive attention and our privacy.

It would be naïve to think that in the Internet a sanctuary free of fraudulent schemes had been created – as naïve as to believe that the Internet is in fact a breeding ground for terrorism and professional crime. Both the mass media and the information media are different sources of conceptualization and knowledge, within which both constructive and destructive forces are at work. They are not utopian self-contained universes.

Post-Monumental Conceptualization

A network culture demands a new form of attention, which you could call ‘post-monumental’: the result of an array of conceptualization and knowledge produced not in a clear-cut, broad-based, institutionally legitimated, authoritative, commercial way or without the potential for interaction. Post-monumental conceptualization is geared toward the gathering of experience and knowledge in an open and dynamic structure of supply and demand. Prior to the advent of the Internet, such structures led a fairly concealed existence. When they came to the surface of the public domain it was usually in a form of epistemological disobedience: in direct action, alternative publications and various forms of protest. In the arts, a long line runs from Surrealism and Dada via Situationism and Fluxus to flash mobs and culture jamming. Via the route of mouth-to-mouth publicity, marginal print publications and improvisation in alternative channels of communication, the content took shape and the audience was reached – sometimes only for the duration of a single public event. In his collection of essays Air Guitar, art critic Dave Hickey recalls the network of out-of-the-way record and book shops his parents would go to in the 1950s to attend poetry nights and jam sessions.5 To the young Hickey’s amazement, these places where like-minded spirits came together could always be found, even in places where his parents had never been before. Such vital networks have always formed a parallel reality in the arts, where knowledge was produced among true enthusiasts and stored in their memory and where interests were shared.

Post-monumental conceptualization is not just the visualization of a post-monumental, post-institutional system. It is also the construction of the post-monumental image. The visibility of the images and their construction as a consequence of an ever-changing interrelationship between content and context are not the work of a centralizing initiative, or an institutional authority. More information is constantly being made available on the Internet, while the objects themselves remain invisible until attention is focused upon them and they are sought amid the supply. Unlike in the old media, the relationship between object and context, thanks to the specific characteristics of the network, is constantly changing, which makes it incidental. The question is how, with incidental connections, we can hold attention for images that remain visible.

This represents a unique challenge for art. Images that endure without having to be pushed amidst media over-exposure using monumental resources and relying on institutional authority require a new artistic consciousness and new artistic methods. Works of art differ from other striking images in that they are systematically produced, distributed and consumed by means of a vast system of established institutions like museums and biennales – in other words, they are systematically brought to our attention. The art system, however, is not solely institutional. It has also operated independently of the institutions. Because these institutions, and by extension art criticism, have reached a crisis, art, for the moment, will have to manage without authoritative finger-pointing. For the organization of the production, distribution and consumption of the arts at this juncture it is imperative that artists and art enthusiasts thoroughly understand the unique potential of a network culture. Only then will the requirements for constituting a lasting post-monumental conceptualization be archieved.

Attention in the Object

Attention produces temporary visibility, but neglect breeds invisibility. The latter is the fate of the traditional monument and of a great deal of art in public space. Enduring visibility occurs only in interaction with enduring attention. If post-monumental conceptualization is to be made resilient, if our visualization of what concerns us, in all its complexity, is to make an impact that lasts longer than the mediatized moment, our attention must literally be invested in the object. We invest in ideas, people and issues in the information age by producing information about them, sharing it and storing it. By directing our attention to the loose linkage of the objects in an informatizing aggregate, we can elicit meaningful connections. Their durability is measured on the modest scale of a casual articulation shared by interested parties. We find ourselves back in the backrooms of the record and book shops. But we no longer have to wonder how we are going to find them again. They come up amidst the concentrated attention of a network of shared interests, which finds its optimum conditions in the present network of communication. Collectivity is created both at the level of a perhaps modest but concentrated attention and at the level of the interest in the principle of interaction between visibility and attention under new conditions. The durability of meaning is guaranteed by the durability of the attention of those who share this meaning. Authorship and readership come together, are shared. In this way, interested parties become beneficiaries. Having moved beyond the competition for attention within a limited number of channels waged by the traditional media, we can relish in the unique features of the huge supply of specialized knowledge and interests the network mediates.

We might thus attempt to imagine a ‘democratization’ of signification. Democratization in a political sense has been contaminated by the idea of the masses, of a monumental ‘people’ – that illusory unity with a preferably shared illusion, with shared ‘standards and values’. But if we manage to reduce this ‘unreliable’ people into the group of ‘interested parties who become beneficiaries’, we witness the emergence of a distinctive effect of the network culture. Attention is invested in objects around a shared interest, forming a non-monumental, non-mediatized, enduringly illuminating context. A context whose meaning we commemorate, as owners of this conceptualization, candles in hand. The post-monumental image is thus a temporary resting point, a loose node in a network of relationships among interested parties and the objects of their predilections, which lasts exactly as long as their interest in these objects. Sharing of the objects themselves and of the interest in them, being at once author and reader, artist and recipient, results in a visibility that is dependent only on the motivation to keep this node in the network, this condensation in the media fabric, intact.

Our post-monumental consciousness distributes attention for new contexts among new beneficiaries. The professional and the true enthusiast get to know each other in new ways and encounter each other in different places. The established order is no longer established enough to impose monumental interests via official institutions in a traditional mediating role. It has been fifty years since any such public order existed. Mediatizing and informatizing forces focus our perception of new and old objects in all directions and manage to hold on to it for varying periods. Every place, every object, every moment and monument, every contextual relationship is informed and absorbed within a new economy of attention. Visibility is not an aesthetic luxury; it remains the basic condition for the acquisition of meaning and knowledge. What we see tells us who we are.

1. From Robert Musil, Nachlass zu Lebzeiten (1936), published in English as Posthumous Papers of a Living Author, trans. Peter Worstman, Eridanos Press, Hygiene, Colorado 1987: ‘Monuments’, p. 61.

2. Maya Lin, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, 1982 (source: www.nps. gov); quotation from www.anecdotage.com.

3. Chris Burden, The Other Vietnam Memorial, 1991 (source: www.archinode. com).

4. www.degrootstenederlander.nl.

5. Dave Hickey, Air Guitar, Art Issues Press, Los Angeles 1997, ISBN 0963726455 (‘Unbreak my Heart, an Overture’, p. 12).

Jouke Kleerebezem is a visual artist, author and researche and teachter. See further: www.nqpaofu.com.