Occupy the University Online

Revising Public History after the Rebirth of Student Protest

August 4, 2015essay,

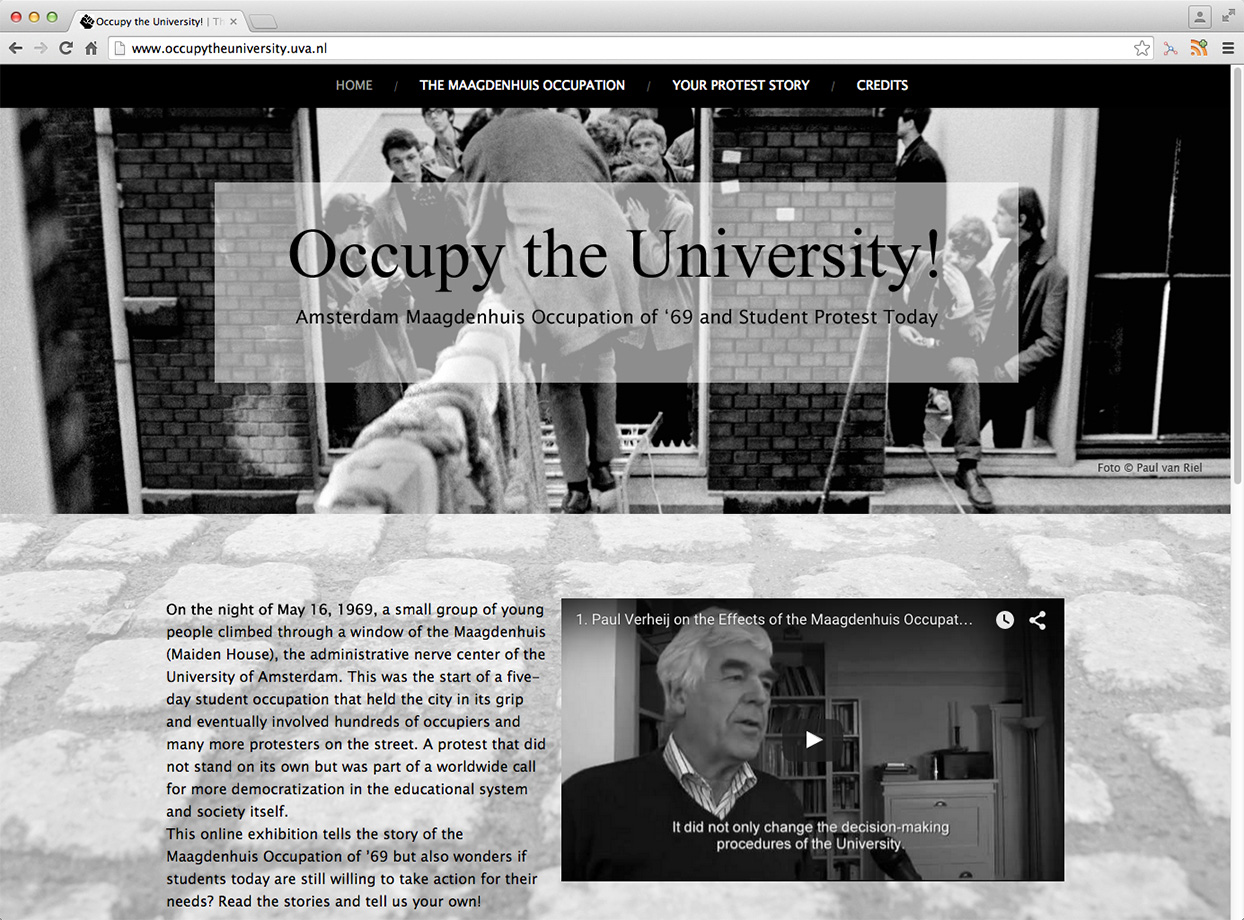

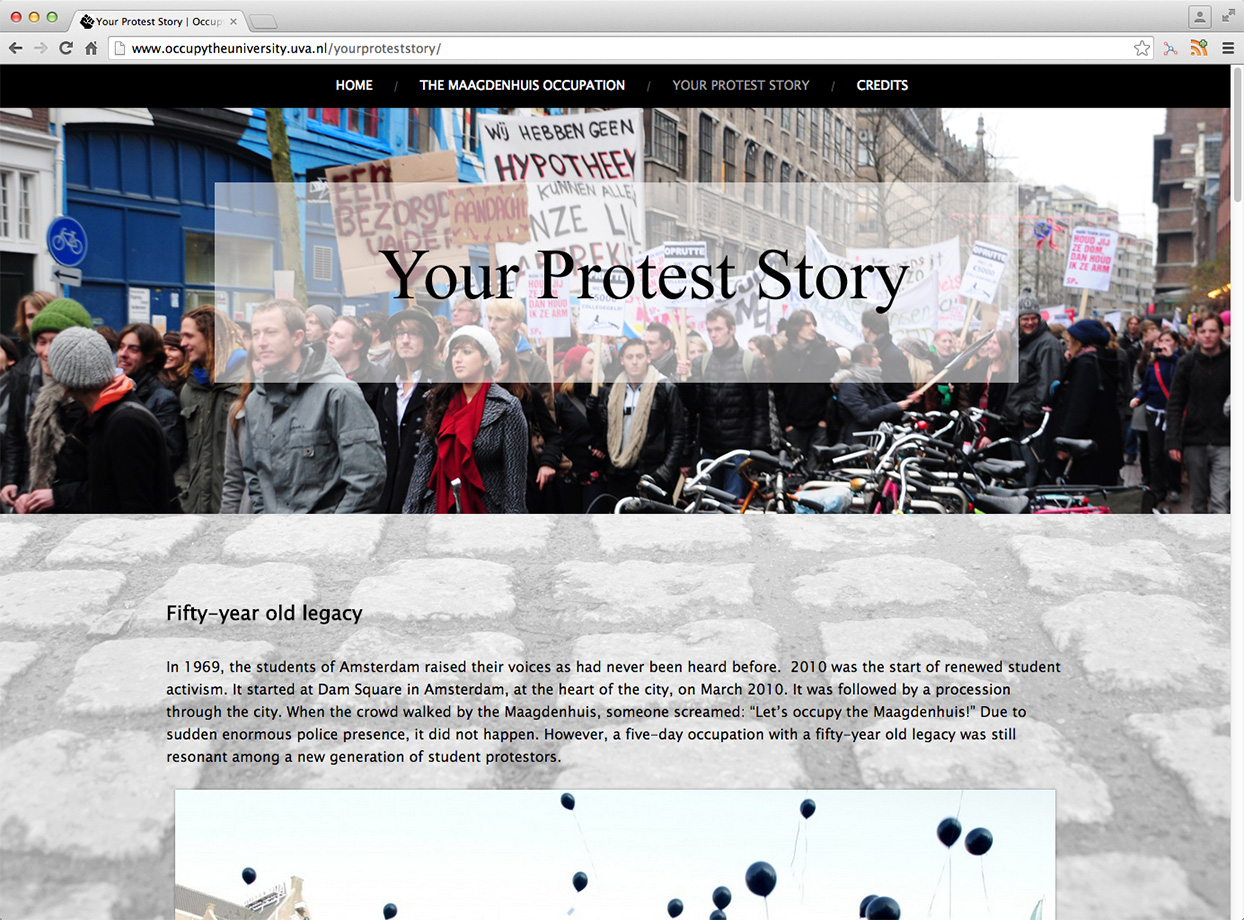

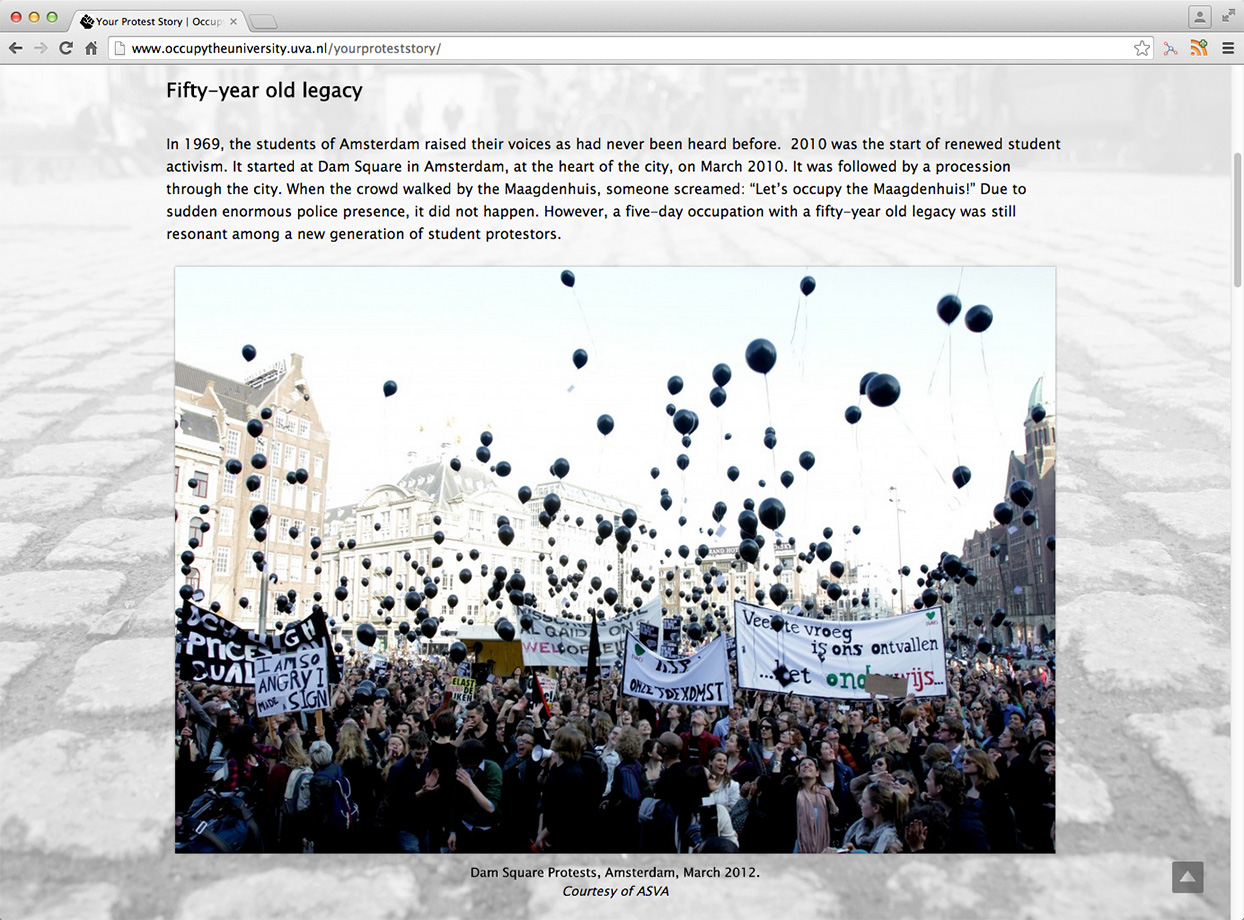

In the fall of 2013, as part of a course on Digital Public History, I supervised a group of students who were producing an online exhibition on the history of the 1969 Maagdenhuis occupation.1 When it was first launched in January 2014, Occupy the University included a brief contemporary section, which prophetically highlighted the legacy of the 1969 occupation as an important touchstone today, which was “still resonant among a new generation of student protestors.”2 Although the exhibition described a limited revival of activism since 2010, the overarching conclusion was that student protest had died off. “In the 1960s, the authorities would not listen to the students,” the text claimed, continuing “now they do, so there is less need to express yourself in a radical way.” Just one year later, such faith in the process of academic governance was drastically diminished, and radicalism was apparently reborn. The 2015 occupation of the Maagdenhuis and the wider protest movement at the University of Amsterdam (UvA) have forced students to reconsider their views on protest expressed on the original website. Their shifting perspectives are the focus of this essay.

I assigned a new project for the 2014–2015 class to mark the 50th anniversary of the Dutch artist-activist Provo movement and their “happenings” in 1965 (which played an inspirational role in the student activism movement during the late 1960s in Amsterdam).3 In preliminary discussions with representatives of the Provo movement and our project partner, the Amsterdam Museum, students struggled to empathise with the young people of this earlier generation as they listened to accounts of youthful alienation and the fight to assert independence and individualism in a conformist and conservative mainstream society. Class members suggested that young people today would find it difficult to understand these protests. This has become a recurring theme I encounter whenever I teach social movements in other classes, in which students often draw sharp contrasts between the past and the present:

| Then | Now |

| Conformity | Freedom |

| Young people were interested in politics | Young people are uninterested in politics |

| Young people thought they could change things | Young people do not think they can change things |

| Activism was the best option for social change | The legal system is the best option for social change |

While several acknowledged that “other people” might face more challenging circumstances, such as poverty or discrimination, overall, those who spoke up generally assumed that University of Amsterdam students were a homogenous group with little to complain about. In fact, although the lack of racial diversity at the university has become a significant issue in the recent protests (as has the racism implicit in some of the responses to the occupation),4 the assumption of equality belies the very real differences amongst this large student body, all of whom are undergoing challenging phases in their lives. The students face personal challenges as well as the stress involved in balancing work and study while they head toward financial independence in a time of diminishing and insecure employment opportunities, declining social welfare support and the rising cost of living. Yet, when the Provo history students were asked to consider how these contemporary issues might affect them, they had little to say. Indeed, in the three years since joining the faculty here, I have been struck by the prevailing sense among my students that they should be grateful for what they have and that the challenges they face upon graduation are apolitical and inevitable. Many seem unaware of social issues that shape their own circumstances, as well as associated cultures of resistance and reform. The result is a general sense that things are relatively good, that some are worse off, but that, in any case, there is not much any one person can do to change things.

When teaching students the core tenets I value in the practice of public history, a major challenge is the tendency of students to adopt a rather passive attitude toward contemporary issues, especially when confronted with the notion that the production of historical narratives is inherently political and that histories have the potential to transform lives and improve societies. The re-occupation of the Maagdenhuis, however, has brought home the international debate surrounding universities in crisis and engaged students in these issues in new ways. Responses to a short questionnaire I distributed to previous and current students revealed mixed attitudes toward the protests, ranging from admiration (“these people were not just trying to kick up a fight, but were really trying to come up with solutions”) to disdain (“they didn’t know what they were talking about”). Whether they were in agreement with the tactics or not, overall, their comments revealed the potential of the Maagdenhuis occupation of 2015 to serve as a “teachable moment” that could address the uses of the past as well as the influence of contemporary issues on the production of historical narratives.

1: “People for a long time thought [that] real student protest was dead”

Student respondents overwhelmingly associated marching and occupation with a former era, (“I had this idea for a while that protesting on the streets wasn’t really of this day and age anymore, but more a sentiment from the past”).5 All of them recognised that the past was employed by both the protesters and their critics, with varying results. One respondent noted that “the students used the past to strengthen their protest and send a clearer message,” but also how critics “dismissed the protesters as rioting, lazy students who, together with squatters, anarchists and communists seemed to in the sixties,” where, presumably, this kind of protest belonged. In fact, the creators of the 2014 exhibition had argued that “people for a long time thought real student protest was dead.” For some students, this was related to the sense that radical protest was no longer necessary, especially because there are improved legal protections in place today, (although these came about precisely because of the Maagdenhuis protests in 1969). Several students, perhaps as a result of the limited impact of the other campaigns since 2010, as well as their apparent lack of knowledge about them, pointed out that their sense that protest had died off was reinforced by the absence of more recent protests against tuition fee increases and cuts in student funding.

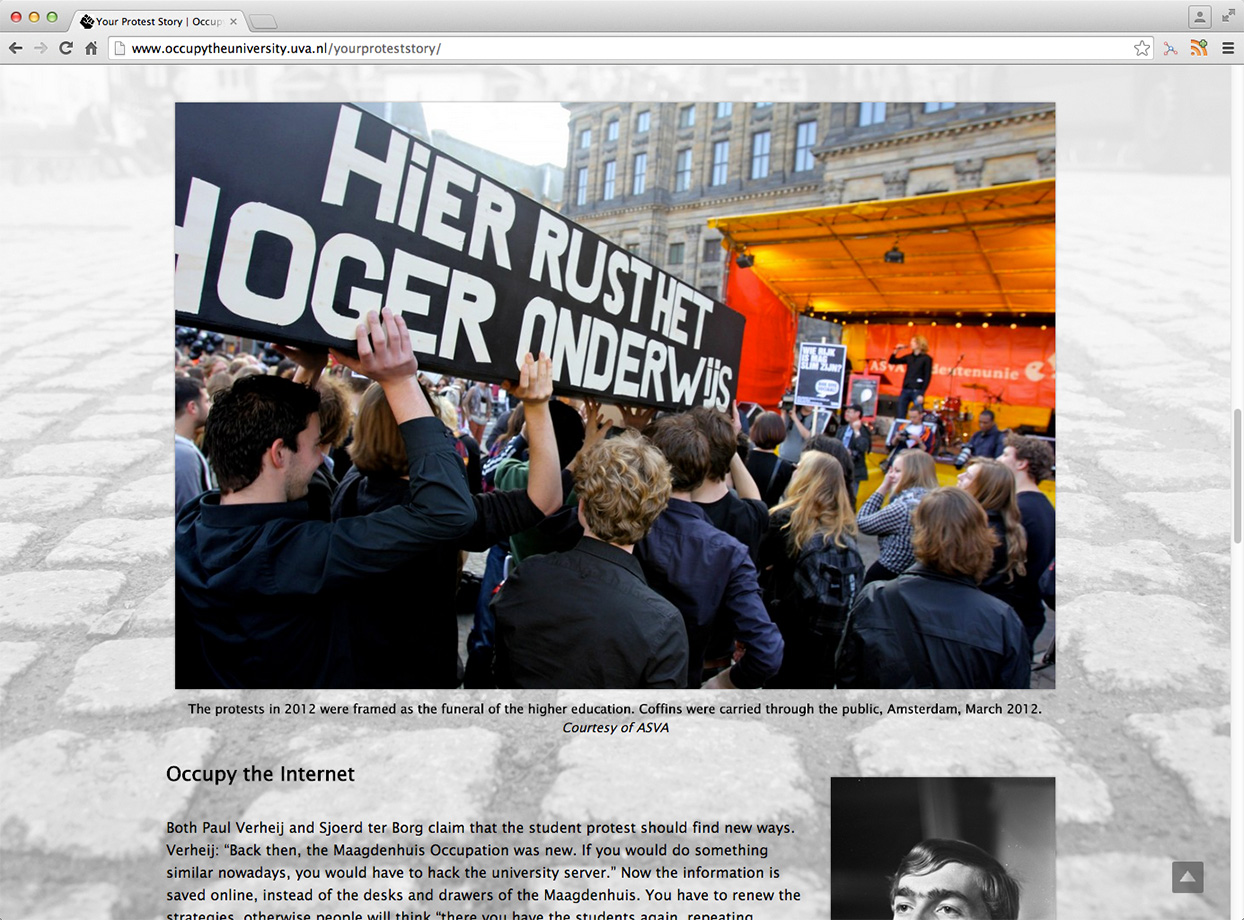

The text for the students’ public history exhibition of 2014 also focused on the idea that the forms of protest have changed since the 1960s, when “more people were willing to do things for their ideals; to do something physically.”6 The sense that fewer students today are willing to participate in such a physical way dovetails with student assumptions that it is less necessary in the digital age (“I believed new ways of protesting would be more effective by using the internet and social media”). The “Occupy the University” exhibition quoted a former protester from the 1969 occupation to make the point:

Back then, the Maagdenhuis Occupation was new. If you would do something similar nowadays, you would have to hack the university server.” Now the information is saved online, instead of the desks and drawers of the Maagdenhuis. You have to renew the strategies, otherwise people will think “there you have the students again, repeating themselves.

In fact, the resurgence of traditional forms of protest during the 2015 events proved to be its most compelling aspect for many of the respondents. As one stated, “I agreed with a lot of points that were being made, but I didn’t really believe a march would change anything, until I saw it with my own eyes.” The impact was no doubt increased precisely because of the notion that these activities are of the past, and not the present.

2: “The students of the Maagdenhuis didn’t have one clear argument”

Both supporters and critics found the protesters messaging less effective. In our class discussions about protest movements from the Civil Rights Movement to feminism, my students frequently misidentified diverging agendas between campaigners as examples of “inconsistency,” “disagreement,” or even “chaos”, mirroring the mainstream media’s framing of the Occupy Movement, for example, in which broad coalitions are criticised for lacking a cohesive argument or consensus agenda.

The same narrative resurfaced in comments about the students involved in the 2015 Maagdenhuis protests (“they are now protesting for humane shelter for failed asylum seekers and during the protest they associated with protest groups from all over the world. … Making it very difficult for a lot of people to understand what they were protesting against”.) This response begins by questioning the link between asylum seekers and students, but then references protest groups “all over the world,” suggesting that the author was also critical of the connection drawn between student protests in the Netherlands and those at other universities.

Other respondents were also confused about the protesters’ goals, as the following statement implies:

The documents that the students back then uncovered [in 1965] clearly show an elite opposing the students, who in no way where taken seriously. If that is the case students are fighting for now, I don’t think the students are protesting for a convincing case.

The respondent went on to say that the “management culture” that others identified as the core issue of the protests is a valid concern, but one that has been imposed from outside of the university, and so students and staff should have taken this issue up with the government instead.

Several respondents admitted that activism plays an important role in a democracy, although with some caveats (“student protests are not necessarily justified or propose the best of answers to the problems they address”). In the week when the Baltimore, United States protests against police brutality were being labelled “riots” in international media, one respondent highlighted the issue of violence, insisting that “only protest without violence is justifiable.” This kind of comment reveals the influence that disparate global current events (and their presentation in mainstream media) have on student perceptions.

I have combined the protesters’ arguments, the target of their complaints and the protest movement techniques here as they became intertwined in this year’s Digital Public History class when several groups proposed framing their Provo history narrative in terms of “police versus protestors.” This suggestion, oversimplifying these social clashes in terms of two opposing sides is striking — and ultimately led to productive discussions about a broader range of viewpoints available in the archive. For example, one group planned to create an interactive game where participants’ responses to quiz questions would either reveal their level of “Provo” revolutionary potential or their empathy for the police. This type of game also raises questions about how and if students perceived the differences in power between the two groups, and what their own attitudes to authority are today.

3: “Money is more important than the quality of education”

“Occupy the University” addressed the contrast between past and present in the nostalgic views of the 1960s rebellion, and, in particular, the notion that today’s protesters are too materialistic and cynical (“Students are too lazy to go out on the streets and money is more important than the quality of education”). Moreover, the Web exhibition’s presentation of the 2010 protests in the Dam Square, highlights the participants’ self-conscious sense of embarrassment that their needs were not as compelling or valid as those of previous generations: “We may not have ideals, but once you touch our money, we will protest!” This tone echoes the general tenor of other classroom discussions in which students minimise the financial concerns of everyone except the extremely poor. However, the exhibition text, quoting Paul Verheij of the 1969 Maagdenhuis Occupation ultimately makes the point: “What is wrong with students fighting for their means of existence? Of course money is important.” Many of these students grew up in an age of austerity politics and seem resigned to the rising costs of education, even while others are campaigning to abolish tuition fees altogether.

In fact, students’ ability to prepare for classroom discussions and assignments are significantly limited by the jobs they take on to help finance their studies. Yet their comments often reveal that this experience remains a personal one for many who have not yet connected their situation to the wider structural framework that created these circumstances. As one respondent argued, protest is “something mostly better-off people can afford to do,” because the only ones with the luxury to complain are those who “have their parents paying for their studies.” These comments, situated amid a series of critical remarks about the Maagdenhuis protest, illustrate how assumptions about the financial circumstances of others can divide students within a university like UvA and shape their attitudes toward the recent unrest.

Conclusion

The Public History students who created the 2014 online exhibition Occupy the University were aiming to emulate the sophisticated digital storytelling strategy of an award-winning online news story that premiered in 2013.7 This visual approach depended on the acquisition of high-quality compelling images, and a complex technical infrastructure that pushed the limits of WordPress. Although they originally intended to consider student protests both in the past and the present, the technical challenges absorbed so much of the development time that the group was ultimately unable to develop the contemporary protest story to the extent they had initially proposed.

These students, along with some other groups in the class, found it difficult to complete their website by the end of the course. Although most were pleased with the results, all of them acknowledged that they had not managed to accomplish everything they had set out to do. Class members tended to characterise this phenomenon as “running out of time” to complete their plans. In fact, they prioritised some aspects over others, with some neglecting the sensitive and labour-intensive work of building relationships to the communities connected to the histories they were producing. In the case of the Maagdenhuis project, this profoundly limited the storyline. As a result, the narrative isolated student protest at a particular moment in the past, even as students all around the world were organising and campaigning against tuition fees and the reorganisation of university structures and activities.

Many of the students involved in the University of Amsterdam protests, from marches to meetings, to arrest and imprisonment, are well aware of their role in making history and are currently actively engaged in creating an archive that will document this movement. A team of students from this year’s Provo class will also collaborate with the creators of the Occupy the University site to redevelop the contemporary section of the exhibition to address the 2015 occupation.

My hope is that this time around, more time to focus on the contemporary story (and the opportunity to meet the protesters, their supporters, and their detractors), even as the ramifications of the protest continue to unfold, will allow them to reflect more critically on the narrative of the death and revival of student protest. At this early stage in their careers as public historians, the recognition that their original narrative will require significant reconsideration and revision offers an invaluable lesson about the dynamic relationship between the past and the present.

1. Dorothée Ramaekers, Koen Molenaars, Michel Lemaire and Laura Piek, www.occupytheuniversity.uva.nl. I divided the class into four groups to create Web exhibitions on topics of their own choosing within the broad theme of histories of human rights. The topics chosen included immigrants and the perception of the Netherlands as a welcoming, tolerant country (At Home in Holland), the history of campaigning at Amnesty International, from letter-writing to digital petitions, (Letters for Amnesty), and the effects of the legalisation of prostitution in Amsterdam (Red Lights, Workers’ Rights). I am grateful to the students involved in the Digital Public History class of 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 for their classroom comments and responses to my questionnaire.

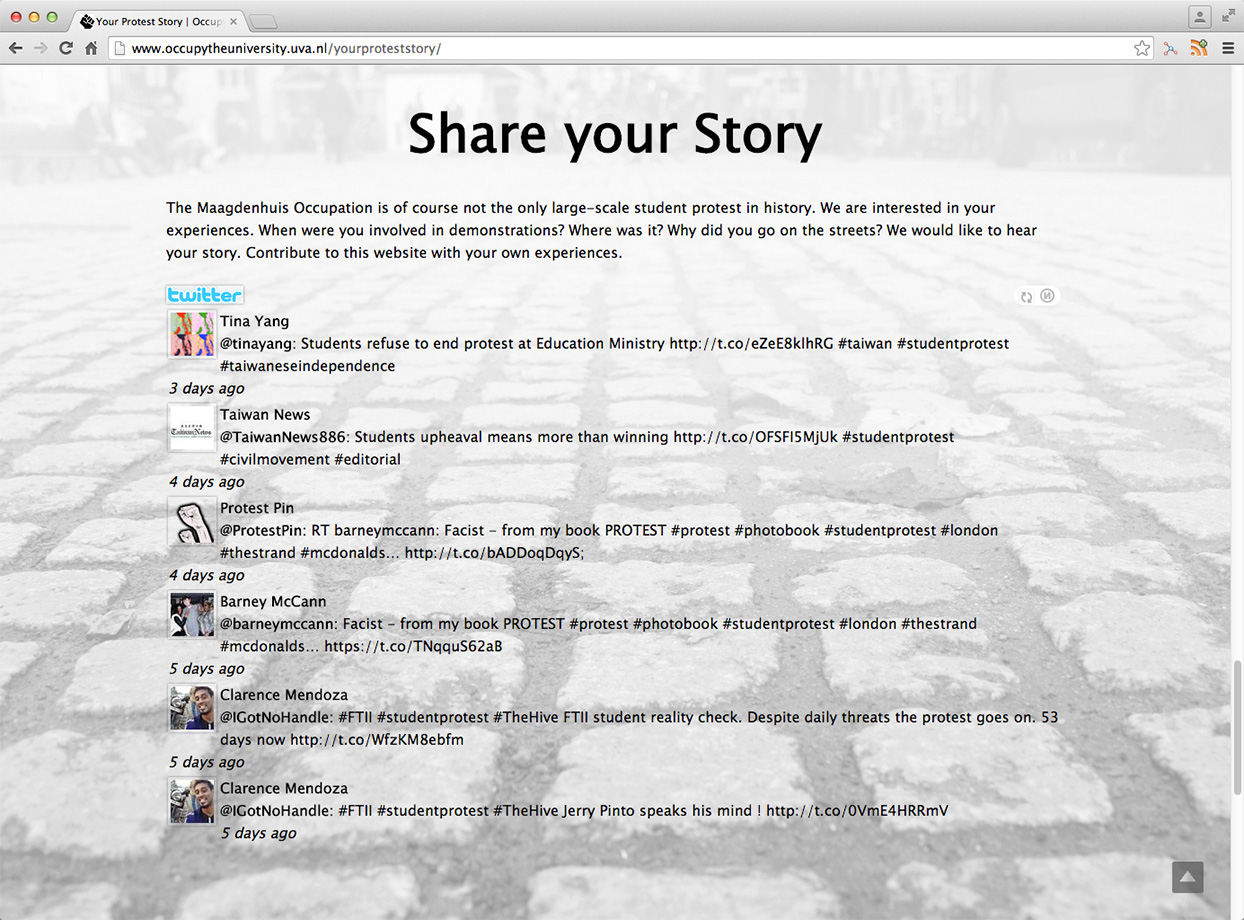

2. All exhibition text comes from the “Your Protest Story” section of the 2014 version of the website. This section will be archived in 2015 and replaced with a new narrative regarding the recent Maagdenhuis occupation.

3. Students developed prototype apps, which focused on the history of Provo happenings at specific sites around the city. The finished version was created by the Amsterdam Museum and draws on various elements of these projects. It became available on 25 May 2015. See www.amsterdammuseum.nl.

4. On the formation and mission of the University of Colour group, see Anja Meulenbelt, “Start of the University of Colour”. On the controversy about university administration statements regarding “presumably Moroccan” non-student occupiers, see Amade M’charek, “We Are the University, Louise”. Also in response to the administration: www.advalvas.vu.nl.

5. All of the students’ responses quoted here come from a short questionnaire that was distributed via e-mail in April 2015 to students who were enrolled in the course Digital Public History in the academic years 2013–2014 and 2014–2015.

6. This exhibition text quotes Sjoerd ter Borg, one of the organisers of the 2010 protests.

7. “Firestorm,” The Guardian, 23 May 2013, www.theguardian.com.

Manon Parry, PhD, is an exhibition curator and Assistant Professor of Public History at the University of Amsterdam. She has curated gallery and online exhibitions on a wide range of topics, including global health and human rights, disability in the American Civil War, and medicinal and recreational drug use. Traveling versions of these projects have visited more than 300 venues in Argentina, Canada, Germany, Guam, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. She is co-editor, with Ellen S. More and Elizabeth Fee, of Women Physicians and the Cultures of Medicine, (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), and author of Broadcasting Birth Control: Family Planning and Mass Media (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013), on the birth control movement’s use of mass media in America and around the world. Dr. Parry teaches on the BA and MA in American Studies, the BA in History, the MA in Public History, and the MA in the Preservation and Presentation of the Moving Image at the University of Amsterdam, and on the MA in the History of Medicine at the Free University, Amsterdam.