A Message from the Future: An Interview with Dr Adelante Revoleis

August 1, 2019interview,

Last December, anthropologist Dr Adelante Revoleis presented their findings on Design History during the Koninklijke Academie van Beeldende Kunsten (KABK) Fault Lines research symposium in The Hague. In this interview, we speak with them on their forthcoming book Advancements in the Study of the Peculiarities of the Rise and Fall of Design History in the Late 20th and Early 21st Century.

Rosa te Velde: Could you tell us a little bit about your research on Design History?

Adelante Revoleis: Until recently, we have only been able to research the phenomenon of ‘Design History’ through the sparse archival materials that would reveal themselves. Some time ago I coincidentally stumbled upon a dusty collection of ‘Design History’ books. Around the same time, the Long-Lost Internet Repository Project granted access to their findings and there I found a collection of Design History articles, mainly from journals such as the Journal of Design History (1977–2029) and I(1979–2024) – a bizarre and extraordinary find, which proved that there was once an academic field called Design History, predominantly practised in the Former West by a small group of specialists. I wondered who they were, what this mysterious practice was all about and why it was so short-lived. This type of investigation will contribute to our understanding of the remnants of practices of modernity/coloniality in the first half of the 21st century.

How would you define the field of Design History?

Despite its potentially wide-ranging interests, Design History was a marginal field of academic inquiry. Since its departure from art history in the 1970s, it claimed that it was concerned with contextual investigations into the social, economic and political aspects of various design objects. Yet, there seemed to be a discrepancy between its self-description and what it actually was: an exclusive canon of sanctified Design Knowledge. Some Design Historians advocated for a dethroning of the designer as the most important figure in the design narrative in favour of a focus on the context of design objects, and on the consumer, while others pushed to broaden its geographic reach, and expand its subject matter. But all of this proved to be too radical for most Design Historians and the Design History textbooks remained largely focused on the Grand Design History Narratives, which included William Morris, Walter Gropius, The Bauhaus, Charles and Ray Eames, and a long list of Scandinavian and Italian designers.

Another defining feature of this field of scholarship is that it was produced by a tiny percentage of people in a confined part of the world, yet this discrepancy was rarely discussed! Most of them were pale, well-educated, middle-class and all were predominantly situated in what was then the United Kingdom, as well as in Northern Europe and the United States. I wanted to know more about this group of people and how and why they constructed and validated the Design Historical field. I wanted to understand their language, their tacit knowledge, rituals, codes and customs.

Could you perhaps give examples of those customs and rituals?

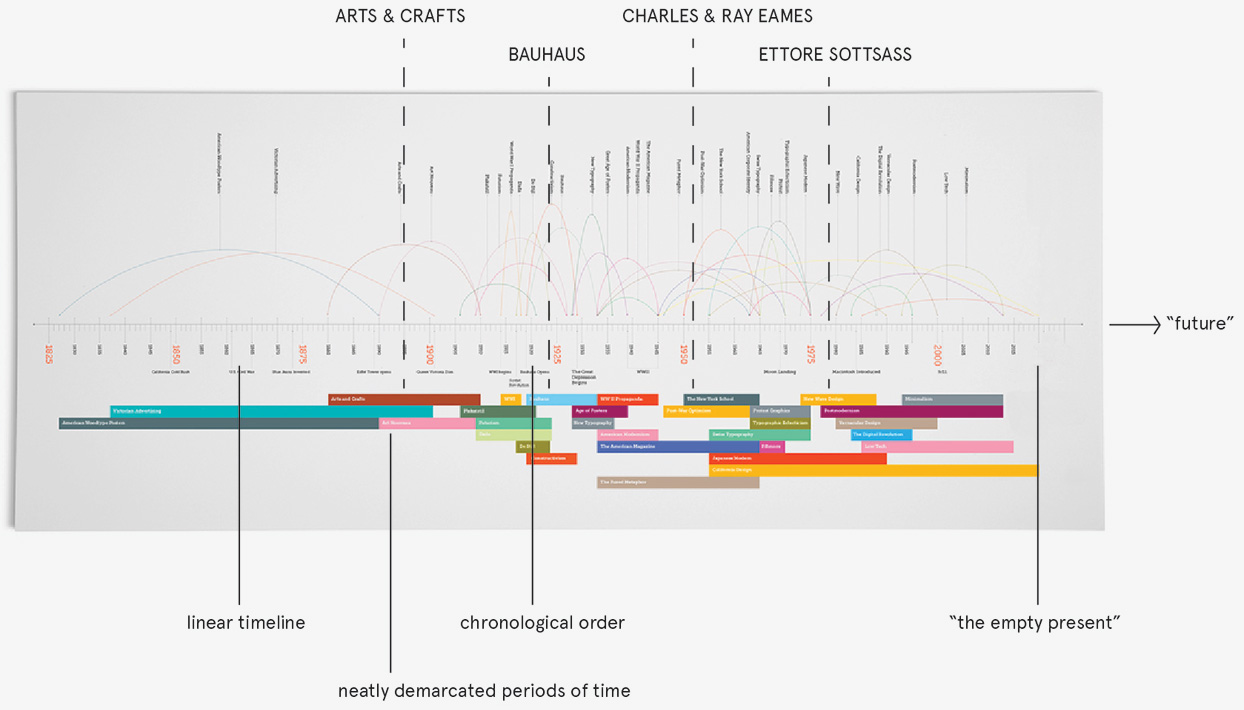

One of the most fascinating customs is that the Design Historians had a very specific understanding of time. In the majority of the Design History books, even in the 2010s, we observe a particular way of ordering information – in a progressive ‘timeline’. In such a timeline, different periods are neatly demarcated, as if one time period was abruptly succeeded by another. Additionally, we can distinguish signs of an intriguing perception of Design History as linear, progressive, showing the ‘now’ as the latest and ‘empty’ point in history, working towards the future (by the way, ‘the future’ is another big thing in Design History). Now, of course, we acknowledge the existence of a multiplicity of time conceptualizations, such as the notion that the past is in front of us, or ideas of circular time. I do understand that the absence of rhizomatic visualization tools made it difficult to adequately visualize ‘time’, but this timeline technology clearly signifies a very primitive time paradigm even for its time. The timeline is also encountered in other academic disciplines and is therefore not exclusively Design Historianistic.

Right. Are there any other habits or codes that you discovered?

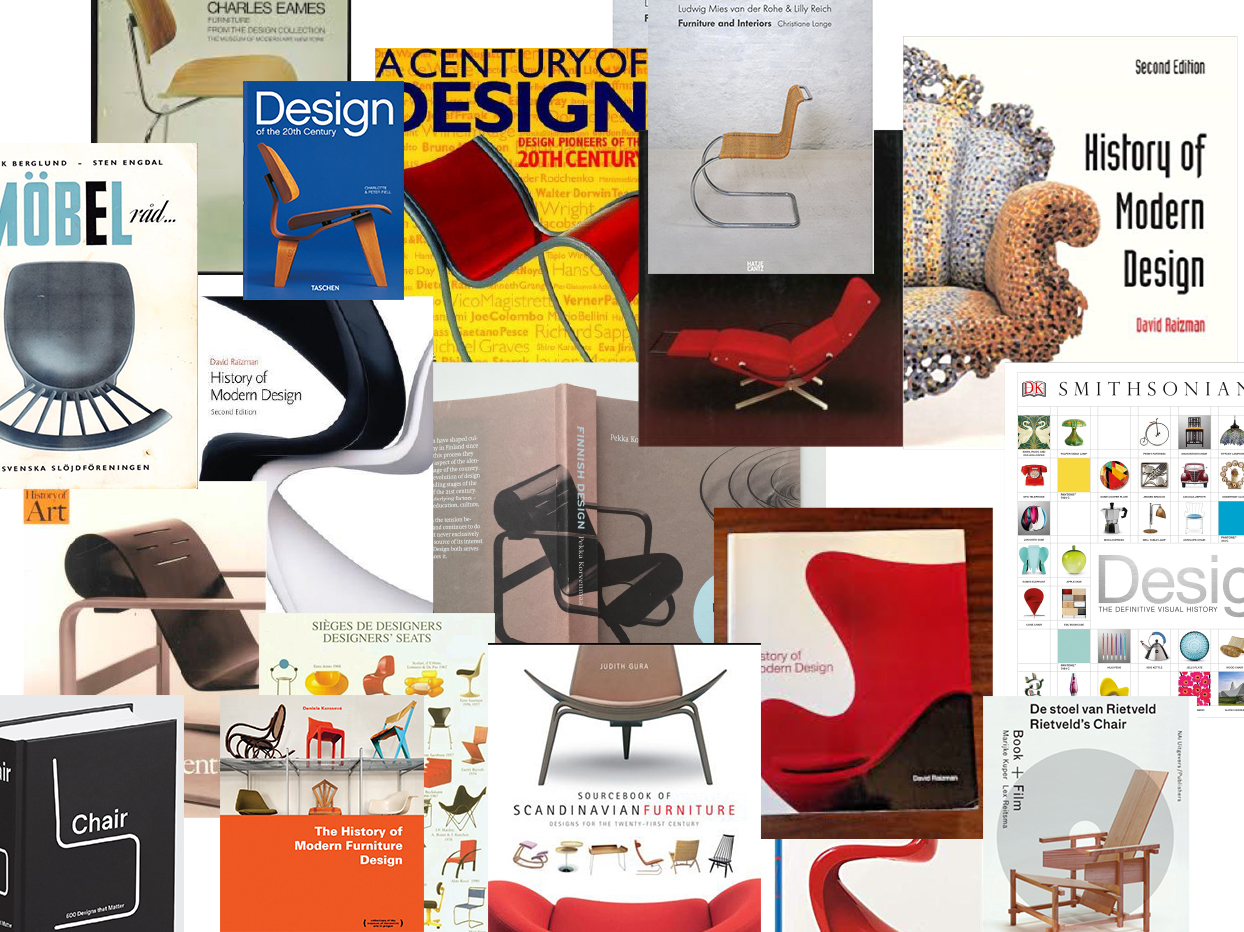

Another shared custom that was prevalent among Design Historians was the obsession with the seating object – the ‘chair’ is what they called it. When I brought this up with some of my colleagues, they immediately argued that this idolatry functioned to uphold and set apart the mythical status of Western superiority. This may indeed be the case, but I think the issue at hand is slightly more complex. Seating objects would adorn covers of the average Design History print book and it seemed a prerequisite – although never listed officially as a requirement to be able to execute work as a Design Historian – to have an almost religious comprehension of seating objects and preferably to own a few exceptional models.

I am planning on conducting a few focus groups with Design Historians here – if I can track anyone down – to gain a better understanding of the significance that was attributed to the now clandestine seating object. It is reminiscent of the trajectory of another, notorious historical product: the cigarette. But the difference was that the chair turned out to be much more detrimental to health. Well of course this was strongly negated by designers before the official WHO ban on chairs. I wonder if it is the ‘temptation of the toxic’ and the ‘appeal of the illegal’ that made them so attractive?

Elsewhere, you have hinted at the interrelation between the locale and the origins of the Design Historians and the fate of the field. Could you please elaborate on that?

Many of the Design Historians seemed to believe that ‘Design’ originated in European modernity. They focused specifically on a mythical understanding of Design as a superior, progressive, ‘intelligent’, intentional practice of form-making and decision-making, as opposed to, what they understood as primitive, ethnic, folk or traditional form-making and decision-making. While in the 2010s these dichotomies were crumbling, in many ways the myth persisted. The inability and the unwillingness to dismantle this myth is the result of what many have called the ‘pale mind’. This disorder can manifest itself in calculative pragmatism, anxieties, competitive destructive behaviour, arrogant ignorance, a lack of curiosity and/or an apolitical outlook on the world, which among academics resulted in eurocentrism and exclusion. This pathology was prevalent in other academic fields too, but somehow this field was even more susceptible to it. Design Historians were too infatuated with their objects of study, in which their own stylistic and aesthetic preferences would often be dominant. The field became increasingly solipsistic and self-referential and in this regard, they failed to critically examine the roots of design in the modern/colonial belief system and became complicit in reproducing it. As we now know, modernity could only exist in tandem with coloniality. Without the acknowledgement of this interrelatedness, Design Historians failed to humble their own belief system, universalizing it instead. It is fascinating that even as late as 2019, the belief system of an ethnic minority persisted so stubbornly. Yet, at the time it was already convincingly challenged by various authors calling for alternatives to the ‘unsettling designs of zero point epistemology’.1

When did the field of Design History disappear and why?

Design History went extinct around the late 2030s. But the first signs of the crisis came much earlier. Some Design Historians were concerned as early as the 1980s and one claimed that ‘design history is in fair danger of becoming an academic backwater’.2 Another researcher stated that ‘Design History’ would become a hobby for ‘winter evenings’. He argued that if design was not more than an inquiry into aesthetics it would become ‘politically impotent for contemporary or future use’.3 In fact, the question of what exactly defined design as a field of research distinct from other disciplines, was perhaps the most consistently recurring topic of investigation as throughout the years it was ‘preoccupied with defining and redefining itself’.4 Another Historian encouraged his fellow colleagues to make clear the relevance of their work to an audience outside of academia.5 And yet another speculated that ‘there is a chance that the term “design history” may disappear’.6 To me, it is clear that Design History was always under threat.

Nevertheless, there was a light upsurge in the 2000s and the early 2010s when most Humanities departments in European universities were in crisis. Interestingly, it was during this period of the ‘Cultural Industries’ hype that in various parts of Europe new programmes – with inventive titles such as ‘Design Cultures’ or ‘Design Futures’ – popped up. It seemed that ‘Design’ struck a chord with neoliberal university administrations that were prone to the perceived market value of the field. Although critics in the field would argue that this had nothing to do with Design History proper.

To what extent do you think the term ‘Design’ is – or was – the problem?

It was a problem, yes absolutely. You know, ‘Design’ was such a confusing meta-concept. It had strong popular connotations and then it had numerous, niche academic interpretations. How to be a ‘Design Historian’ when you fundamentally have trouble explaining your subject? I have observed that around 15–20% of the articles in the professional Design History literature is dedicated to explaining how the author understands ‘design’. There has always been a lot of confusion and anxiety around the term ‘design’. The obfuscation took off in the 1980s, the so-called ‘Designer Decade’, when the term started to proliferate, and it came to an all-time high in the late 2010s. The easiest – but at the same time most problematic – way to establish ‘Design’ as an object of study was to stick to a narrow understanding of it. This is the tragic paradox of the field.

Apart from that, the practice of Design itself was deeply embedded in the violent act of selection, erasure and exclusion. Processes of mystification and decontextualization were part and parcel of the field. The quest for newness and innovation always depended on extraction of the earth and exploitation of people in one way or another. Without a critical distance, Historians were unable to bring these dynamics to the surface.

Did they do anything to prevent the field from going extinct?

Somewhere in the 2010s a campaign was launched to save the Endangered Field of Design History. Some Design Historians agreed that to remain relevant, they should embark on an expansionist mission in order to extend the territory of the Design Historical map across the world. Sadly, this generated even more tensions as many of these design historians claimed that design is a human practice taking place across time and space, while others were interested in seeing the so-called ‘development’ of the rest of the world through design and wondered what took them so long. It’s hard to believe the echoes of the saviour complex being still so prevalent in this decade! They welcomed Design Historians from other parts of the world, but allowed them only to talk about their own local design cultures. We now clearly see how all of this is related to the well-known problematics of the pathology of the destructive pale mind.

Was the extinction of ‘Design History’ inevitable, according to you?

I would argue that a broader dissemination of a proper self-reflexive study of the politics of the field could have offered plenty of opportunities to understand its dynamics in order to broaden the field and its relevance. But, most design historians were unable to reach beyond their own horizon of thought. Design Historians were too much in awe of their object of study, caused by a historical tunnel vision. It is very difficult to imagine this practice differently. But this is a complex question and needs further research, some of which I do cover in my book Advancements, which I do hope your readers will consider purchasing. It has a very nice seating object on the cover…

Dr Adelante Revoleis (2044, Kautokeino Islands) is Professor of Cultural Anthropology at University of Skjervoy. They are the co-author (with Ovard Tselee) of Latent Violence: Ethnographies of Pallidity, now in its third edition. During their career, they were a recipient of the Wolfgang Dante Oen Lie Fellowship in 2071, President of the Polar Oval Institute (from 2075-2079) and the winner of the Cultural Cosmo Horizons Prize in 2083. Over the past years, Dr Revoleis has dedicated much of their time to the discovery of the field of ‘Design History’.

1. Matthew Norman Kiem, ‘The Coloniality of Design’, PhD thesis, Western Sydney University, 2017. Other authors and initiatives include: Madina Tlostanova, Arturo Escobar, Tony Fry and the Decolonising Design Platform.

2. Fran Hannah and Tim Putnam, ‘Taking Stock in Design History’, BLOCK, no. 3 (1980): pp. 25–33.

3. Tony Fry, ‘Design History: A Debate?’, BLOCK, no. 5 (1981): pp. 14–18, quoted in Kjetil Fallan, Design History: Understanding Theory and Method (Berg: New York, 2010), p. 15.

4. Jonathan M. Woodham, ‘Local, National And Global: Redrawing the Design Historical Map’, Journal of Design History 18, no. 3 (Autumn 2005): pp. 257–267 (258).

5. Victor Margolin, ‘Design in History’, Design Issues 25, no. 2 (Spring 2009): pp. 94–105 (104).

6. Joanne Gooding, ‘Design History in Britain from the 1970s to 2012: Context, Formation, and Development’, PhD thesis, University of Northumbria, 2012, p. 339.

Rosa te Velde graduated from the designLAB department of the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam in 2010, after which she obtained an MA in Design Cultures from the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam in 2015. Her main research interests revolve around the politics of design and (national) identity (exemplified by concepts such as Dutch Design), decoloniality, race and gender. Together with Steyn Bergs, she is co-editor-in-chief of Kunstlicht, a journal on art, architecture and visual culture and she is also a board member of the Dutch Design History Society. She works as a freelancer for Sandberg Instituut (Studio for Immediate Spaces) and at the Royal Academy of Art in the Hague.