Following the Fault Lines

Identifying and Contesting Sites and Spaces of Drone Surveillance, Colonial Knowledge Production, Digital Pollution, and Extraction through Art and Design Research

August 2, 2019editorial,

Each year the Royal Academy of Art (KABK) in The Hague makes provision for a selected group of its tutors and staff to work on a self-defined research project in the context of a Research Group. The nature of these projects varies, from research driven by and through one’s own artistic or design practice to historical or theoretical research; from material or technological research to academic research in preparation for a PhD trajectory. In monthly meetings, participants discuss progress and questions related to methods for research and analysis, theoretical concepts and modes of dissemination. Alice Twemlow, lector Design at the KABK and Chair of the 2018 Research Group, introduces (image) essays by Rachel Bacon, Rosa te Velde, Niels Schrader and Donald Weber, which are distillations of individual research projects and are published in two batches.1

Taking as our metaphorical conceit the geological concept of fault lines — fractures in the planet’s surface, along which movement and displacement occurs — we addressed the changing contours of contemporary art and design research as the borders of disciplines shift.2 How does art and design research inhabit the fissures between disciplinary realms and negotiate the discontinuities between them? What is the frictional or generative potential of such interstitial positioning? Are there particular qualities and capacities of art and design-specific research tools and methods and what do they allow for?

The concept of fault lines allowed us to map and interpret an array of pressing issues, including the convergence of airspace and dataspace, a colonial-modernist bias in design history, digital pollution, and climate change. How can we reveal and resist the expanding geographies of drone surveillance? What are some strategies for critiquing design history’s Eurocentric modes of knowledge production? What are the environmental and psychological impacts of our ever-accumulating data detritus? What is the role and position of the artist in a time of ecological crisis?

Rachel Bacon, an artist and tutor at KABK in BA Fine Arts, conducted a research project that explored the relationship between the additive, mark-making quality of drawing, and the extractive one of mining and how an understanding of this relationship might lead to an artistic practice capable of addressing ecological crisis, or what Timothy Morton calls a ‘traumatic loss of co-ordinates’. This led her to a new way of understanding drawing, as a form of touching and witnessing. The drawing methods arising from this approach include folding, rubbing and layering, and visits to sites of exploitation and excavation.

Eric Kluitenberg teaches theory in KABK BA ArtScience, MA ArtScience, and BA Interactive / Media / Design. In his earlier work, Kluitenberg proposed a spatial model, known as Affect Space, as a way to understand the affective intensities generated during the public gatherings and urban spectacles that have been taking place over the past few years in cities around the world — from Zuccotti Park in NYC to Tahrir Square in Cairo, and from Gezi Park in Istanbul to the streets of Hong Kong. With their unique intermingling of (mobile and wireless) technology, intense on-line (mediated) and off-line (embodied) exchanges, in the context of urban public spaces, these gatherings produce a new dynamic that is highly unpredictable. While unpredictable, this dynamic is in no way arbitrary, however, and, furthermore, it is highly susceptible to manipulation. In his more recent collaborative research, Kluitenberg and his colleagues in the ‘reDesigning Affect Space’ project have explored what types of design agendas might be used to counter such manipulation, and to distribute agency (the ability to act effectively) more equitably across the different actors operating in this space – citizens, corporations, public agencies, ‘creatives’, civic organisations, local, national, and transnational authorities.

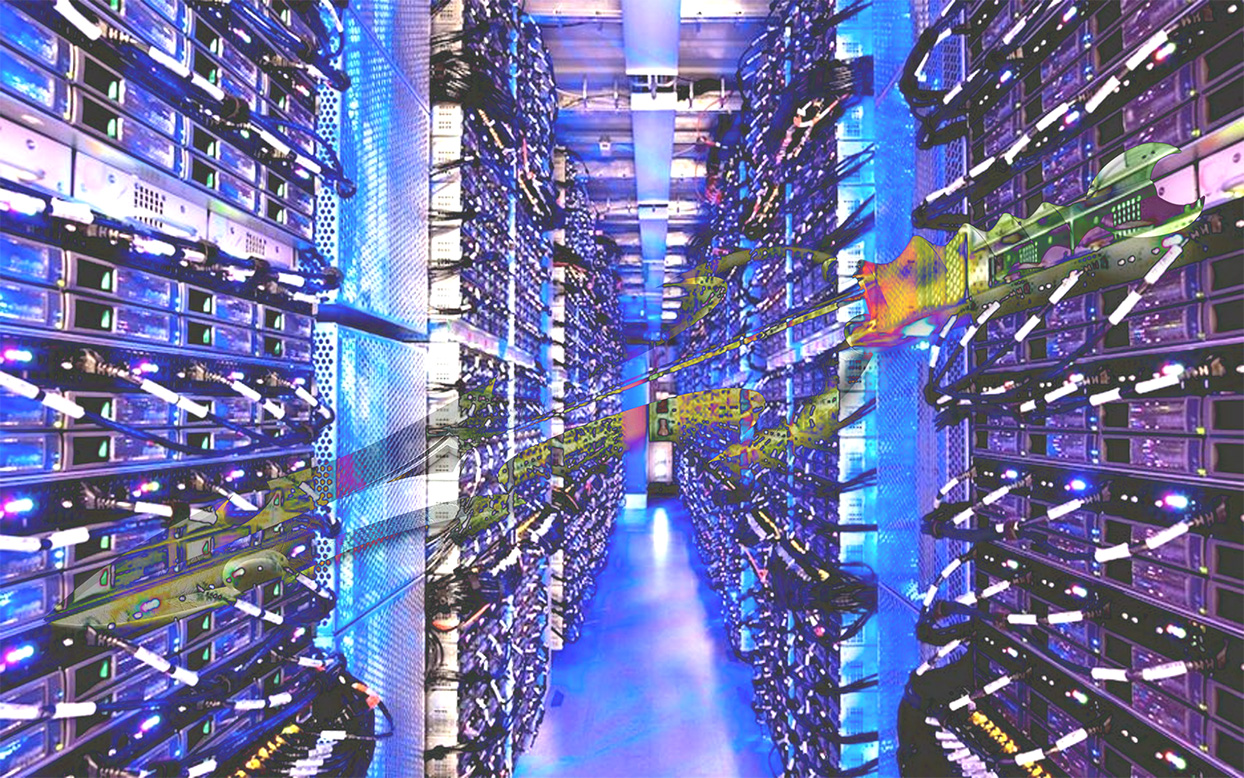

Niels Schrader, co-head of BA Graphic Design and MA Non-Linear Narrative, looked at what happens when the resources needed to create, share and store our daily output of 2,5 quintillion bytes of so-called ‘virtual’ data encroach on the physical environment. In his project, Schrader used online tools such as Google Earth and published online media in combination with site immersion and visual analysis, to reveal the hidden aspects of a selection of data centres in the Netherlands. Through his research, Schrader provides us with a means to understand and reflect on the impacts and implications of what he terms ‘digital pollution’.

Rosa te Velde, a design historian and designer who teaches in the Research & Discourse programme and a theory tutor fo rBA Interior Architecture & Furniture Design at KABK, explored in her project how fiction might be used as a strategy and research method to disrupt design history. In her lecture 'Making Design Weird Again' she inhabited the perspective of a fictional anthropologist from the future in order to expose Eurocentric and colonial biases in the production of design history. Through these measures, te Velde sought to challenge a range of design history tropes such as the linear timeline, canon, ideas of Western development and progress as well as notions of humanity, issues of individual authorship, appropriation and the dominance of the visual, and to create space for critique.

Donald Weber, a photographer who teaches in the BA Photography and MA Photography & Society programmes at KABK, researched how the convergence of airspace and dataspace is radically changing the production of worldviews. In Geographies of Power Weber appropriated satellite imagery from Google Earth to explore how airborne machines manufacture and condition the spaces of a securitized and surveilled society, arguing for the importance of making the hidden indices of (drone) power intelligible, vivid, palpable and contestable. Using this method of counter-reconnaissance, based on French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s inversion of surveillance into ‘counter-veillance’, where he sought to turn the prison inside out and ‘watch the watchers’, Weber allows us to see drone infrastructure not just as a geopolitical agent, but an infrastructure and ecosystem that encloses life itself.

When we met as a group to reflect back on the year’s work, I put some questions to the researchers:

What changed for you during the process of working on your research project whether in terms of what you thought research was or in the way you conducted it? What is different for you now?

RB: I had a lot of reading to do in order to grasp the discourse in the relationship between art and ecological crisis. So, for me it was like cramming a two-year graduate school programme into one year. As an artist I am constantly doing research – in the sense of exploring places, materials, themes and everything that goes into making a work. But that is quite different from academic research. I am looking forward to continuing to figure out how to meld together those two approaches.

Rosa, we saw your project change a lot over the course of the year. Did your views on research also change?

RtV: I started my education as a designer before entering a university environment, which is where I started to write. I feel that through this Research Group, I went back to a more designerly, less academic, and free way of working and it was really liberating for me. I feel that I have found the trick to making research in different ways.

NS: I am not a writer such as Rosa, so my needs are different; but I also learned that my confidence also comes from doing visual research and approaching it in a very different way than anyone else would probably do it. The Research Group gave us the opportunity to sit down and really take the time to figure these things out. For me there was a very clear moment where I thought ‘I think I can actually do things again’.

There are also the tools that you developed to gather the research that were really interesting: the visual comparative analysis you made of the different data centres.

NS: Yes, I had done this kind of thing before, but I was not conscious of it as a tool. I remember there was a day when you asked us, ‘What are the methods that we use?’ and that was really good because that forced me to examine the way I work, and the process by which I get somewhere by doing something. Before that I wasn’t conscious of using it as a research method.

RB: One of the ideas I really take away from this process is how to clarify that the method is this tissue between the idea and the form. This is where I learned the most for myself in terms of how I can go about making things. My methodology comes out through making a drawing and all the implications and resonances that has on other levels. Research enriches the way of approaching something that is very practical. Thinking about mark-making – that’s huge already.

EK: What I liked about the group was that we come from such different backgrounds. That has contributed to the fact that we also learn from each other. I was fascinated by learning about visual research methodology. Through this you encounter things that you would not find through academic research. If I then look at my own practice, I also do not consider myself an academic. I always position myself as part curator and then on the research side as a theorist. For me, theory deals with something very basic and simple, which is the formation of concepts. Although I’ve been working on the idea of ‘affect space’ for several years, I’m much happier with what I’ve done in this Research Group, because I have been able to go from the theory and get much deeper into the concept, be much more precise. In this group I could test some ideas. I quickly realized that people need the phenomenon of mass groups in public spaces to get into the idea of affect space. It was clear this project had to turn back towards something experiential.

What was a significant moment during the research trajectory?

RB: For me it was visiting the coalmine in Germany. I was there for only a week but it was really important; I should have been there onsite for a month and done drawings in the trees.

NS: Mine was also realizing how important field research is – that I have to witness and experience the data centre buildings.

Right. As I remember it, you found one of the data centres on a bike ride…

NS: Yeah and I thought, ‘this is sort of odd…’

I think that most research starts exactly from that phrase: ‘this seems odd.’ It’s about noticing when something seems out of place, problematic or significant.

RtV: For me a nice moment was when I started to make the collages; I felt this freedom to produce things that were not in an archive. Another turning point was a conversation with a friend, trying to explain my project and he said to me, ‘Ah, okay so you’re trying to make design weird again’. That was really helpful.

How does your research connect with your role and teaching at KABK?

EK: Actually, I coined the term ‘affect space’ not in the essay but in a course I taught at KABK, because I needed something short and catchy to get it across to the students.

That’s a key point, isn’t it? Perhaps our efforts to engage and catch the attention of our public, including students, helps us bring our research to life. Rosa, do you see yourself folding these strategies of fictionalizing design history back into your teaching?

RtV: I was asked by KABK to teach the basics of design history and the canon, but that was something I questioned. This project was very much connected to how I introduced the course. I literally had an image of an alien, thinking about sociology and how we study the alien figure and with that image later on I realized that was how I should approach my project here as well. And yes, I am finding new ways to use the fictional lens in my teaching.

And Rachel, I know that you have developed an elective for KABK students. Does it relate to your research?

RB: Yes, I am going to work with the students on how to move back and forth between idea and form. I want to introduce elements of what I have struggled with, and learned from, in the past year in terms of how you go about putting all this information you have into the work and what that does. How do we as artists connect the information about the world, about concerns with political issues, with ecology, that we are researching into own work.

Niels, you’ve always valued research and teaching the Graphic Design students research skills. Has the way that you teach research changed in any way as a result of this Research Group?

NS: I think my approach has become more structured; now I have a clearer sense of the range of methods available to us as design researchers and I’m keen to teach that to the students in Graphic Design. But I’d also like to say that for me, participating in this group was mainly about separating out a space from my teaching and for my own research.

What is next?

NS: I have the feeling that I’ve only just started. I’m excited that I can tackle this subject matter through visual research, through producing, rather than writing.

What about you, Rachel? What are your next steps?

RB: I love the idea of an exhibition. It keeps the focus on this research that results in form-making. I was also approached by someone who attended our Fault Lines symposium; they invited me to put in a proposal to go to Russia. I’m also interested in connecting mining and drawing by through moving image to animate the drawing in addition to collecting moving image of mining. I need to put those two forms of mark-making together.

1. Eric Kluitenberg is also part of the Research Group. As a result of a collaboration in which Kluitenberg acted as a guest editor, Open! previously published material from the research project into technology / affect / space. Find the editorial and links to the publications here.

2. On December 2018, the Lectorate Design organized the symposium 'Fault Lines' at KABK. Find more information here.

Alice Twemlow is a Research Professor at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK) where she leads the Lectorate Design with the theme Design and the Deep Future. She is also Associate Professor at Leiden University in the Academy for Creative and Performing Arts, where she supervises design-focussed PhD candidates. Previously, Twemlow was Head of the Design Curating & Writing Master at Design Academy Eindhoven, and before that, she was Founding Chair of the Design Research, Writing & Criticism MA at the School of Visual Arts in New York. Twemlow writes about design for a range of publications, including Eye, Dirty Furniture, frieze and Disegno. She has a PhD in Design History from the Royal College of Art and Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and is the author of Sifting the Trash: A History of Design Criticism (MIT Press, 2017).