(Against) Neuralgia. Care of the Brain in Times of Cognitive Capitalism

Lexicon

August 13, 2017artist contribution,

Open! COOP Academy Publishing Class 2016–2017 – a project with the Dutch Art Institute (DAI) – has been investigating the state of the mind and brain under the conditions of cognitive capitalism. We focused on current notions of the brain in our global capitalist societies and questioned in how far the brain can be ideologically infiltrated. From the assumption that culture and brain form complex systems of influence, control and resistance, and that language, memory and imagination are more and more performed by machines and automated algorithmic procedures, we looked at some of the implications of ‘cognitive automation’ for our subjectivity, identity and free will. We explored how neuro-scientific conceptions of the brain are appropriated by cognitive capitalism and charted possibilities to subvert the instrumentalization of our brains. This lexicon is one of the results of the project and a collaborative work by the Open! COOP Academy participants.

Bodymind

Verena van den Berg

You see your screen, clicking on links that lead to articles – the cursor took you were you choose to go and so seemingly, did your finger. But did it? Controlling our body, objects around us and reflecting on our actions, makes us see a self independent of surroundings. This leads to identification with abstract inner processes, which we distinguish from the biological matter of our bodies. Separation of mind and body seems the only logical conclusion. But this line of reasoning is in fact only possible through activating our motor and perception systems; our body’s ability to move and sense. We conceptualise through our bodies only and our metaphors are based on physical experiences.1 This intricate interdependency of rational and physical functions made philosopher William Poteat talk of bodymind. Dancer Mary Whitehouse suggested that the body changes through working with the mind and the mind changes through working with the body. Considering their interconnected mash this could be rephrased as: engaging physically leads to new information. If our perceiving bodymind in motion, which drives our conceptualisation, is sensitised and triggered in its response-ability, we are able to perceive more accurately what is out there.

Changeover

Maya Watanabe

Je, Je, ma, nous. Je, vous, vous, vous. Il, votre, vous, nous. Vôtre. Ou il était dans l’autre sens? What voice is this that speaks within me? Ou était le vôtre? Che ne sarà di me? Il mio futuro sarà come vivere con un altro sé che non ha nulla a che fare con me. Dovrei andare a fondo di questa diversità che mi avete dimostrato e che è la mia vera e angosciante natura? Ξέρετε τι τα σύνορα; Αν περπατώ, Είμαι αλλού. Oh, am I? Am I? Non, il n’y a personne ici, je suis seul. Maybe it’s both. Maybe both are happening at the same time.2

Conversion

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen

Dear all,

I am about to become anonymous. It feels slightly painful thinking about it. I close my eyes and imagine what it will be like.

My body heats up, a sense of fear gets into my bones.

How does it feel to be a complete unknown?

How does it feel to be like a stone?

How does it feel to not be able to feel?

I am about to make a big change in my body and settle down.

> reproducing >> budding >>> and dividing >>>>

At the end, will I regret it? Will I be able to think, or to feel regret after that part disappears? The thought constantly runs through my mind, storms around in my brain, and makes me sick to my stomach.

In the process of movement, I have been flooded by information and have fed on the cultures of others. Changes appeared, shifting from warm to cold, from messy to organized, from organic to artificial.

.

.

.

I sink.

By moving around I finally find my place, a place I can call home.

I am losing a beloved treasure and there is no turning back.

Curling my spine, breathing air through seawater, I slowly lift my body up from a rock. I lie down, finding the right spot.

The process begins.

I attach my mouth to the rock, and begin to pull in my tail with my guts twirling. I will miss swimming after all.

My eyes close, I start to feel seawater flowing through my body. I feel like I’m exploding.

Inhale…

Exhale…

Then…

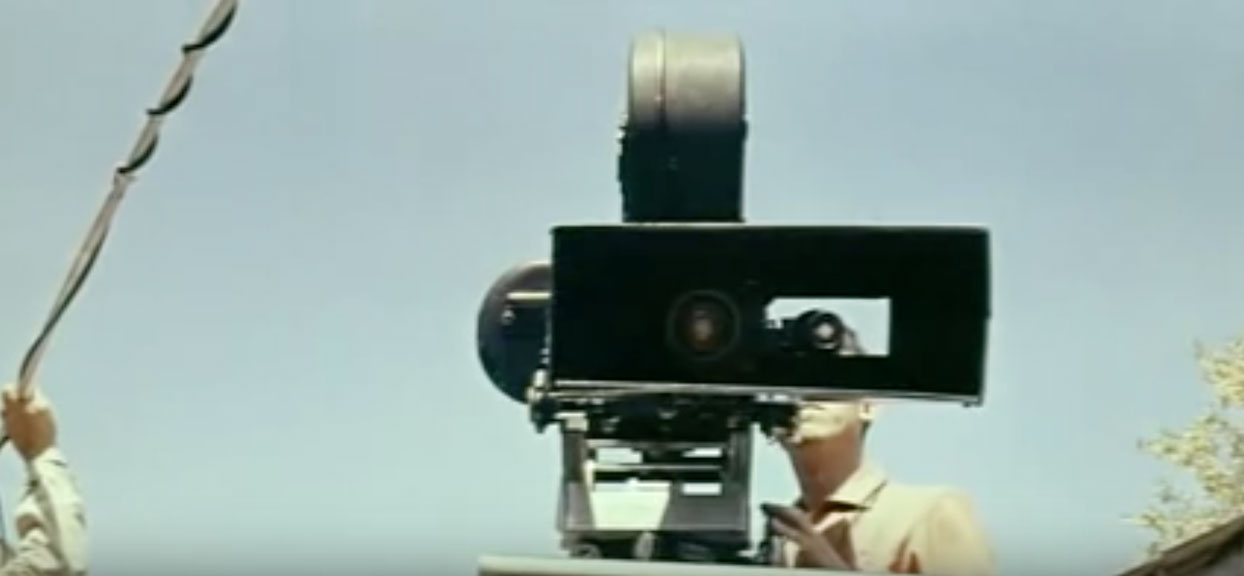

Cosmetic Semiotic Expansion

Katja Dendulk

The human body can be considered a ‘complex form of mediation’ that is a ‘structure in development’ (Bernadette Wegenstein, Getting Under the Skin, 2006): the human body is employed as a means for communication of stabilized conceptual content. A semiotic game of transmitting and receiving resides in a collective enterprise of body enhancement. With the increasing popularity of cosmetic surgery as commodity and the privatization of cultural production, the body-image vocabulary has been heavily expanded. Such an expansion of cosmetic vocabulary is shifting cultural norms and seeing them ramify into a plethora of previously unimaginable trajectories – which is a vector directed at embodying media itself: advertisement, pornography and other fictions. On the one hand, this cosmetic expansion works against the idea of collectivity due to an increase in conflict between cosmetic norms and ideals and the endorsement of a growing plurality of subcultural tropes. On the other, it clusters communities through mutual negativity. This body ideal is a fictional body-image whose approximation is attempted either through technological development of cosmetic enhancement or structuring the maintenance of the body following increasingly logistical guidelines: for example, militant gym practice and the privatization of nutrition expertise. Cosmetic vocabulary’s rapid expansion is exemplified by the actuality of the contemporary fashion industry operating more along the lines of trend-watching than actual design and invention. In times of cognitive capitalism it might be worthwhile to extrapolate on how the exponential growth of a fracturing and stagnating cosmetic vocabulary is going to inform society on a political level.

Helltro

Areumnari Ee

Moaning

Smell of sweat

Humidity

Tangled hair

…

These are the basic conditions of the helltro.

Mr. Gu must endure them for thirty-four minutes each morning in order to attain his ultimate goal: arriving at his first job on time and in a state of devotion ready to work. He firmly stands behind this goal, with his face worn-out before the day has even begun.

When he boards the metro his body gets stuck in the crowd. It is fixed in this position automatically. But his mind, relatively free of concern, leisurely attends to the things he sees, hears, smells and feels. ‘Leisurely’ is one of his skills. Today, he has unfortunately ended up right in the middle of the subway car. He detects a sharp edge, a nasty odor makes him frown, he hears an arrogant tone of voice speak into a phone, the aggressive pace of online gaming advertisements hurt his eyes.

He closes them, imagines becoming a different self, outside of his immanent condition. This is another skill he has acquired. He senses recent changes in this helltro, which is not quite hell anymore. Right now he feels no pressure. He feels free, though this isn’t easy to explain: he enjoys expanding the realm of his limited condition away from the central power. ‘I am my synapses.’3 He thinks.

Perhaps he was let in on a secret; he is no longer a machine that takes commands. He reacts subjectively to his own environment. In this helltro full of an invisible force, he doesn’t feel the same as he did before boarding the train. But thirty-four minutes is not very long. His stop is coming. He will get out as soon as the train reaches Seolleung. He should stick to a linear way of thinking and find his own way through the crowd. He is just a test subject in a case study, experiencing a moment of subjectivation in the helltro.

myOur(self[selves]);

Malcolm Kratz

my.environment(digital) crystallizes by every interaction with my.self(image), which in turn sculpts a more defined image of mySelf();

i take shape through every interaction with my.environment(digital), that fits my.self(image), which in turn ascertains the image of mySelf();

my.self(image) slowly becomes my.environment(digital), while i, mySelf(), arrange my.environment(digital);

with every interaction we, my.self(image) and my.environment(digital), construct a clearer image of ourSelves();

my.tethered(model[self]);

my defined my.self(image) that i put in to and is crystallized by my.environment(digital);

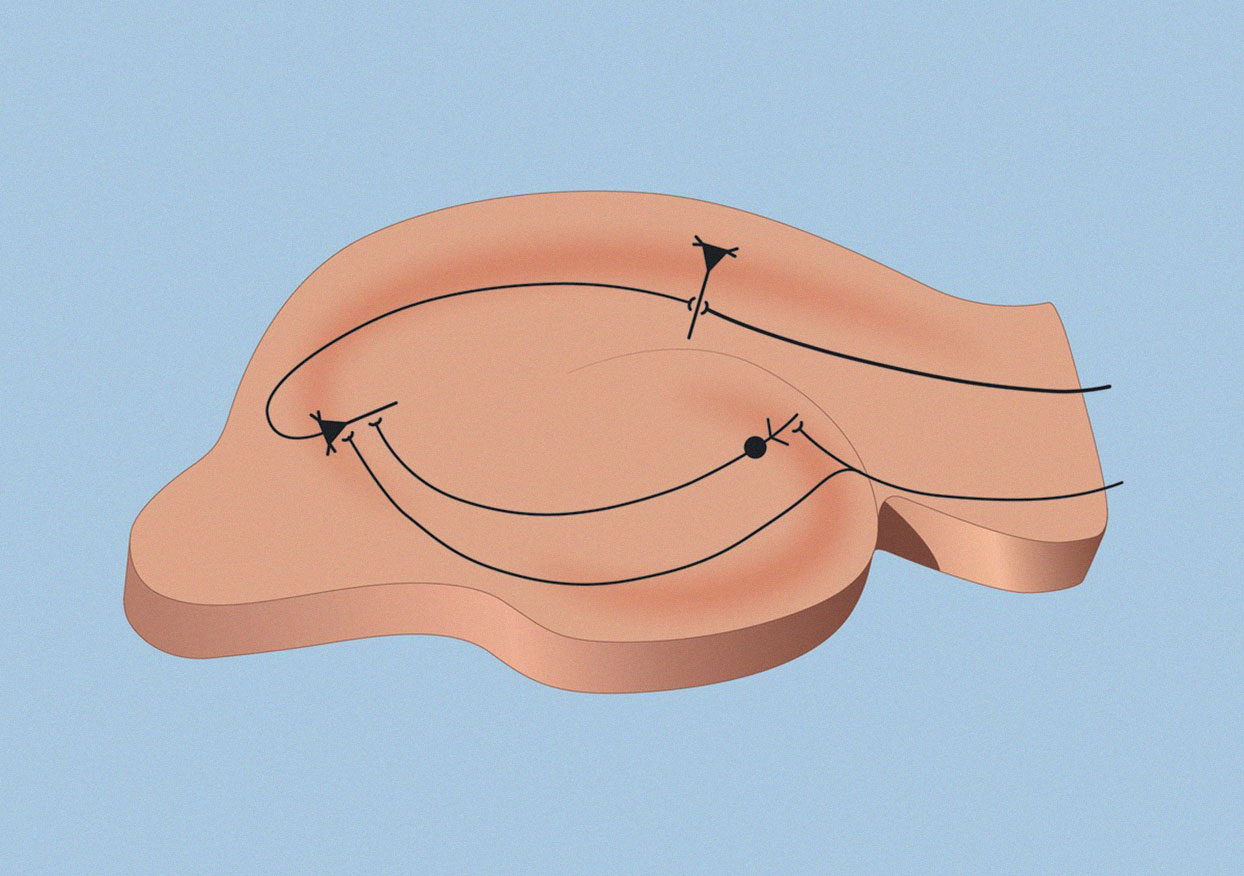

On Contingency

Mira Adoumier

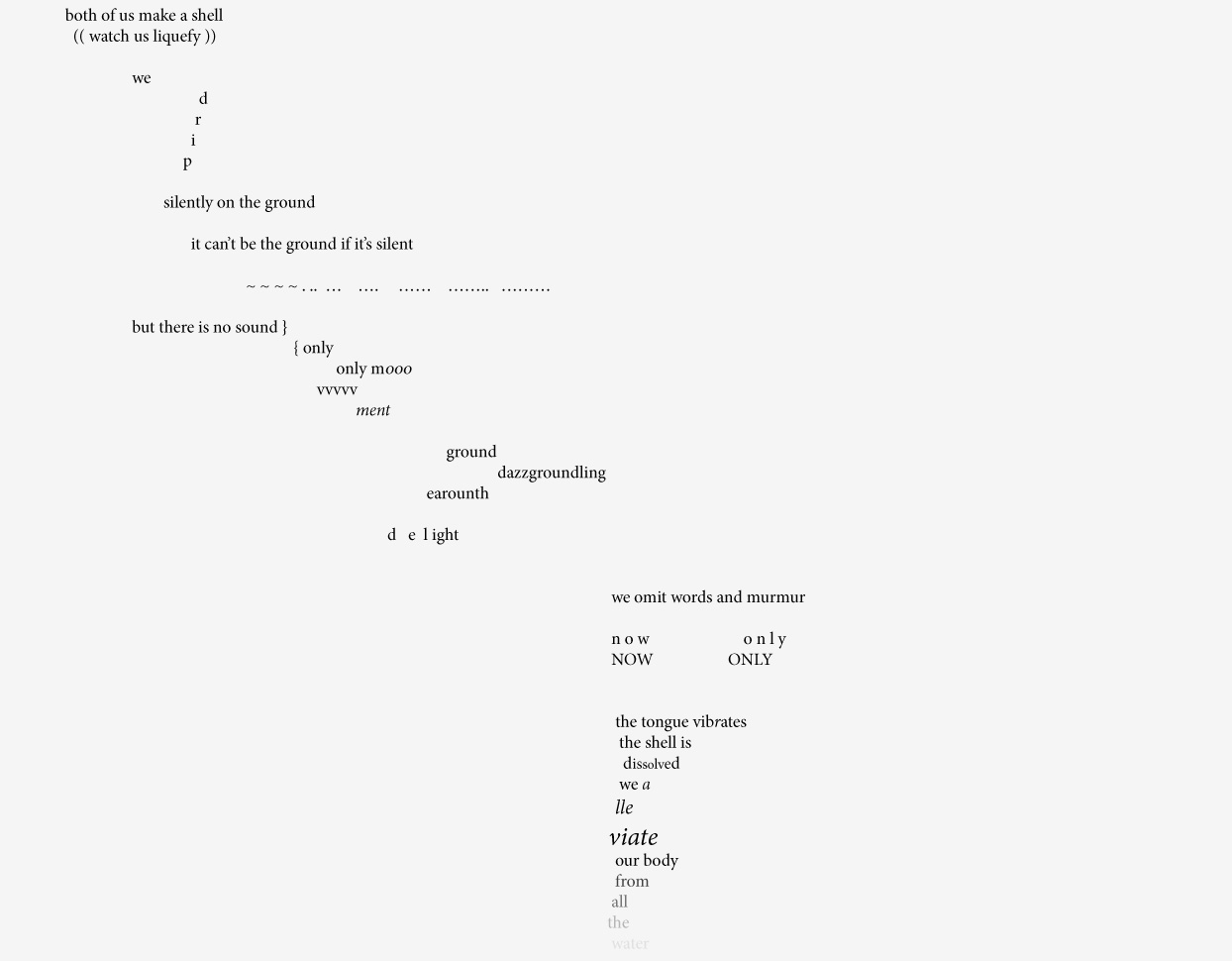

Let us for a second imagine a stray bullet hitting a plate of glass. Such an event can be described as purely contingent, accidental, or even disastrous if someone were to stand at this particular point in time behind that glass. Around the point of impact, a concentric web of cracks forms, as a consequence in time of this hazardous encounter. No matter what the nature of an encounter, be it in matters of love, politics, art, or science, it operates in a similar manner, hinging on pure chance or contingency. Think of this network of cracks as a network of interconnected neurons and synapses, forming new connections after each experience, each event in our life. Such is the principle underlying brain plasticity. Take as an example of an event, a random encounter between two persons. Let us assume that this encounter marks the beginning of a love affair. Love always starts with an encounter. Suddenly, this random point in time morphs into the assumptions of a beginning. Alain Badiou would argue that the result of this event, this bullet, is so charged with novelty and experience of the world that in retrospect it cannot seem random and contingent. Quite the opposite: it becomes a necessity. In a way, our neurons interconnected by synapses find themselves rearranging their network of connections after this event. A retroactive activity starts taking place, in which suddenly memories of past experiences and events rearrange themselves retroactively. They rewrite and even change the past, in such a way that everything in our mind seems to have necessarily led to this event. Instead of the cracks resulting from the point of impact, the cracks would then lead to it. As a result, this encounter with pure chance becomes a raison d’être through the intricate work of neuronal plasticity. Our past histories converge to bring us to this point. As Badiou notes, what appears as an absolute contingency of the encounter with someone I didn’t know finally takes on the appearance of destiny.

Śūnyatā

Wilfred Tomescu

Floating miles above the lunar surface, Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins is thinking of the potentially fatal outcome of his crewmates’ mission. A speech prepared for Nixon reads:

Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.4

That he alone might be the only one to return to Earth – and the notoriety that comes with this – presses on him.

Entering the forty-eight-minute cycle behind the moon, all contact and communications stop. For the astronaut, objectively valid reality ceases to exist.

Perhaps in a moment of overwhelming pressure under a vast universe of possible thoughts, a single neurone fires its only signal.

The electrical charge received at the other end fails to reach the -55 mV threshol5 and the accumulated impulse is released in the form of muscular convulsions.

Abrupt and absurd laughter fills his tightly sealed tin capsule and brings about a sudden feeling of seclusion. In the ensuing quiet stillness, he writes:

I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it.6

He uses the terms ‘awareness’ and ‘almost exultation’ to describe his experience, achieving a solipsistic yet meditative state of cosmic assonance.

The Washington Post prints the headline ‘“The Eagle Has Landed” – Two Men Walk on the Moon’7 and Michael Collins is forgotten. Much like Schrödinger’s cat, he at once is and is not.

Trigger

Agata Cieslak

Yesterday me and Angela went to visit Julie at her workplace. Since Julie returned from Montenegro she has been recruiting for the San Diego ZOO. She also runs their social media site.

Although the outside was covered with ice and snow, we felt like we were in South Africa. The ZOO has a real rainforest with floods and storms. The local embassy sends illegal migrants from Somalia and Nigeria to work there as pirates. The ZOO has its own subway system, airport and – obviously – corporate secret service.

There is a restaurant located in the clouds, so you can see natural sun lighting. We ordered the gorilla bouillon and bird dog with artichokes and cornflower salsa. But, if you want to feel more secure, you can order things like pork or veggies.

At the end of the day, we did a parachute jump to escape a fake fire attraction. I felt like a ninja in a Chinese horror movie. Thank God I had my Nikes on.

Voice

Benedicte Clementsen

She has unlimited access. Her external flexible intellect is relieved from the burden of storage, all changes saved in drive. She thinks in fragments. Reality, she insists, is both multiple and plural, fully capable of overthrowing old masters and disrupting existing power structures. The noise that she emits is an unwelcome guest that overwhelms the monolithic voice of tradition. The circular, smooth gestures of her thumb rub against the interface as she sweeps her way through temples of authenticity, tearing down their pillars at fiber speed. This is the reality in the midst, and the mist that lies ahead. They used to say she had her head in the clouds. This was not what they had in mind.

1. George Lakoff, Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and Its Challenge to Western Philosophy, (New York: Basic Books, 1999).

2. From the movies: Bande à part, directed by Jean-Luc Godard, 1964; Sans Soleil, directed by Chris Marker, 1983; The New World, directed by Terrence Malick, 2005; Teorema, directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968; To meteoro vima tou pelargou, directed by Theodoros Angelopoulos, 1991; Fight Club, directed by David Fincher, 1999; Chambre 666, directed by Wim Wenders, 1982; Bande à part, directed by Jean-Luc Godard, 1964; Forrest Gump, directed by Robert Zemeckis, 1994.

3. See Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do With Our Brain (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008).

4. Bill Safire to H. R. Haldeman, letter, In Event of Moon Disaster, 18 July 1969, www.archives.gov.

5. The value of membrane potential (the difference in electric potential between its interior and its exterior) of a neurone under which it would not react to a received action potential (electric impulse).

6. Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journey (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009), 402.

7. Thomas O’Toole, ‘“The Eagle Has Landed” – Two Men Walk on the Moon,’ Washington Post, 21 July 1969, www.washingtonpost.com.