Art and Activism in the Age of Globalization

November 18, 2011review,

Lieven De Cauter, Ruben de Roo and Karel Vanhaesebrouck (eds.), Art and Activism in the Age of Globalization, Reflect #8, Rotterdam, NAi Publishers, 2011, isbn 9789056627799 and isbn 978905662, 334 pages

In evolutionary biology, a special place is reserved for the island dweller. Because of the relative isolation of islands, the evolution of the species living on them took a remarkable turn. Safe from the threats of the mainland, from the existential struggle with the species living there, island dwellers developed the most peculiar characteristics and spectacular superfluities. They were extremely focused specialists and often also nonconformist eccentrics. Languid, meditative giants and jaunty birds unable to fly survived for millennia thanks to their isolation – until the inevitable moment when the invasion came from the mainland, and the specialists and eccentrics proved powerless to defend themselves.

The contemporary artist was an island dweller. But what long was a world unto itself can no longer be just that. The arts are under fire. Dramatic cutbacks in culture are in the works. The art world’s attempt to defend itself comes across as shaky and ill at ease; its arguments hardly find a response beyond its own circles. The appeal to civilization, the shared message of the art protests thus far, only confirms the cliché. It evokes the image of an arrogant art elite that has been propagated with great success by the rightwing government, an elite that proclaims itself and its system of subsidies as ‘civilized culture’. In this context, the issue of artistic engagement, for years a returning and unsatisfactory debate, re-emerges with renewed intensity. Producers of art and culture are assiduously seeking a new public role, a rearticulation of their relation to the broader community, a new political stance against the spleen vented from The Hague.

So the compilation Art and Activism in the Age of Globalization, the eighth volume in the Reflect series by NAi Publishers, comes at a good moment. Add to this the publication by Pascal Gielen and Paul de Bruyne, Community Art. The Politics of Trespassing (Valiz Publishers); the first volume in NAi Publishers’ Reflect series, Nieuw Engagement; and the recent tract on cultural activism by bavo, Too Active to Act (Valiz) and it would appear there is a good basis for carrying out the discussion on an engaged art practice to full satisfaction. The disputed character of the word ‘engagement’ in itself shows the necessity of this debate. The concept has become tainted, its meaning reduced to well-intentioned participatory projects, its impact minimalized by artistic servitude to existing policy agendas. It is a position the English critic Claire Bishop once compared to that of the female lead in the film Dogville: her uncritical desire to serve the community only furthers her subjection.

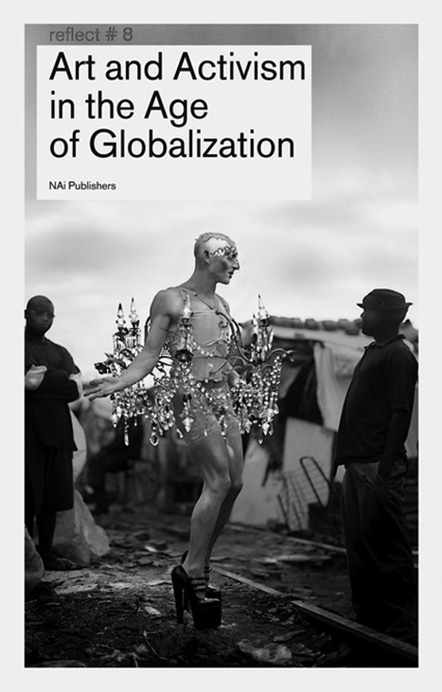

The political art projects filling the pages of Art and Activism stay far away from this subservient position and are unrelentingly sharp in their artistic criticism. We read about avant-garde theatre from New York, about the queer performance art of the South African Steven Cohen, about the Argentinean Erroristas and their performative undermining of the visual idiom of the war on terror, about the way in which Christoph Schlingensief used his body to analyse the social condition, about the Parisian flash-mob campaigns to re-conquer public space from the advertising pillars, about artistic inquiry into colonial historiography in Belgium. We read about uncompromising American underground cinema, about a director who is principally objected to a breakthrough, about Renzo Marten’s Enjoy Poverty, that most painful of attacks on the political economy of development aid, about theatre makers who are supporting the sans papiers in a difficult process of self-questioning instead of affirmation, about Mexican-American gay performers who attempt to penetrate the armoured identities and intensified border controls of the usa after 9/11.

You might expect that such an impressive series of projects would be accompanied by an impassioned introduction, a call to take up artistic arms. And apparently that was the editors’ original intention: a guidebook for new generations on the necessity of subversion, how to turn the complex and problematic tension between activism and art into something productive. Something strange must have happened. Instead, the volume exudes a feeling of nostalgia and depression. Lieven De Cauter’s introduction can best be read as a funeral speech for artistic protest and aesthetic subversion. After this interment, De Cauter calls for defensive and affirmative action – that is to say, defence of what we still have left: human rights, the welfare state, the environment. In Karel Vanhaesebrouck’s essay we read that art’s role in portraying a different society no longer matters, now that change is no longer a real possibility. From now on, we should focus on the most prosaic: human survival. We find the same depressing approach taken by Rosi Braidotti, whose article seems to have provided the inspiration for the strange jump from subversion to affirmation that De Cauter makes in the introduction. Mass political activism, according to Braidotti, has nowadays been replaced by ‘processes of public and collective mourning’. Not so strange, then, that her article reads like a therapeutic session to reconcile participants in aesthetic resistance with their losses, only to subsequently refer them to the affirmation of their ‘non-unitary subject’. And then there’s Ruben de Roo, who in a peculiar manner manages to read The Author as Producer, Walter Benjamin’s key text on artistic engagement, as a call for individualistic art, as much as possible devoid of any ideological inclination. It is difficult to misread Benjamin as badly as that.

The strange thing about the editors’ ‘affirmative’ approach is first of all that the power of modern art lies precisely in its tension with the existing order of things, in the depiction of possible worlds. We don’t need art for propagating the here and now, we can simply open the newspaper for that. Secondly, their approach seems to be in open contradiction with the majority of the art projects discussed in the book: aesthetic subversion is not dead – it is simply buried alive in De Cauter’s introduction. Subversion and imagination are also abundant in the other theoretical contributions in Art & Activism. Brian Holmes provides a subversive cross between the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari and cybernetics. Rudi Laermans argues for commonalism, a new politics of the common, and John Jordan talks about his laboratory of the insurrectionary imagination. Gie Goris and Christophe van Eecke conclude with a ruggedly inflammatory tone. Those who want to change something, we read, must take risks: Change something. Make a difference. Go screw some government tonight.

As such, the book somewhat manically totters between desperate depression and cheerful agitation, between introverted mourning and high-spirited determination. Perhaps this contradiction is precisely what makes the book more than a good collection of prominent political art projects and penetrating theoretical essays. It makes this volume a faithful reflection of the contemporary state of mind.

Merijn Oudenampsen (1979, Amsterdam) is a sociologist and political scientist. He is affiliated to Tilburg University, doing a PhD research project on political populism and the swing to the Right in Dutch politics. He was guest editor of the 20th edition of the art journal Open, titled the Populist Imagination (NAi 2010). He edited a volume titled Power to the People, een anatomie van het populisme (Boom | Lemma 2012). His essays and other texts are archived on merijnoudenampsen.org.