Bigger and Brasher

April 13, 2005review,

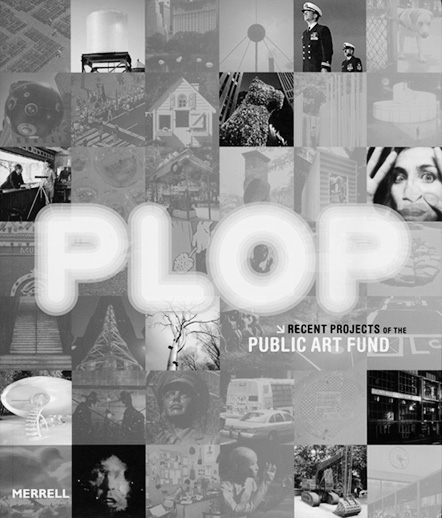

Plop: Recent Projects of the Public Art Fund, edited by Tom Eccles, Anne Wehr and Jeffrey Kastner, Merrell Publishers, London / New York 2004, ISBN 1858942470

In the late 1950s, I perused photographs of Canada and the United States which were sent by family members who had emigrated there to those of us left behind. What have always remained with me are the snapshots of cousins, toddlers at the time, next to enormous, white cupboards. When my parents purchased a standard-size fridge a few years later I clicked that those white things in the photos were refrigerators, but substantially bigger than the one in our house. Over there, everything was much bigger and brasher, automobiles included.

That same feeling hit me when I read Plop, a survey spanning more than 15 years of art in New York’s public space. The book provides an outline of developments since the 1960s and presents developments since the 1990s in detail. In a certain sense these developments run parallel with those in the Netherlands, except the works of art are a bit more substantial: modernist sculptures next to modernistic buildings and on public squares in the 1960s and ’70s (Tony Smith, Mark Di Suvero); more autonomous and more figurative in the 1970s and ’80s (Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg); textual and graphic in the 1980s and ’90s (Jenny Holtzer, Keith Haring); situational and socially oriented in the 1990s and at the turn of the new millennium (Dan Graham, Rachel Whiteread, Christian Boltanski, Pipilotti Rist, Mark Dion, Paul McCarthy). All the works of art considered are emphatically or perhaps overly present in the streetscape, and their physical impact is therefore considerable – no subtle hovering on the periphery.

The book puts 46 artists on parade, many of whom have also left their mark in museums or in the (semi-) public domain in the Netherlands, such as Vito Acconci, Alexander Brodsky, Juan Muñoz, Tony Oursler and Tobias Rehberger. Whereas art in public space in the Netherlands is still usually subsidized and financed by government, directly or indirectly, the financing and organization of projects in New York, and probably throughout the United States, is a ‘public-private partnership’. However, this makes little difference to the way it is organized. From the highly readable texts, by Tom Eccles and Dan Cameron in particular, it is possible to deduce that there is little difference in insight between here and there about how projects are conceived and organized. On both sides of the Atlantic, promoters of art in public space must contend with biased attitudes within the art scene that art in this domain can be characterized as weak or of poorer quality, and that it actually merits only one qualification: compromise art. Having to defensively stand in the breach for the realization of art on the street is therefore not an exclusively Dutch phenomenon.

There are also many similarities as regards the position of the commissioner or delegated institutional supervisor. Their advisory, wait-and-see approach to what the artist would make of a commission shifted towards a role as co-organizer, producer and participant. Another parallel is that once realized a work of art can no longer stake an eternal claim to a given site, and there is always one particular instant that proves critical for that change of site. This is captured well in Tom Eccles’ observation that the removal (i.e. demolition) of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc in 1989 coincided with the installation of the engaged billboard work by Felix Gonzalez-Torres in memory of the Stonewall Riots in the West Village two decades earlier.

Plop describes the development of art in the public space of New York, and in a material sense its evolution in the Netherlands, perhaps throughout Europe, can also be described as shifting from being rock-solid and intended for posterity to fleeting and extremely temporary.

More and more publications about art stand out for leaving out visual material. Modern-day contextualization has resulted in an essayistic art criticism which has become so autonomous that images have become almost superfluous, or only serve to substantiate what is asserted in a text. This cannot be said about Plop, at least, which is a volume with plenty of illustrations offering an attractive overview of the development of art in New York’s streetscape.

Tom van Gestel worked as the Head of the Visual Arts Commissions agency of the Ministry of Culture (1983–1995) and then joined the Mondrian Foundation, where he held the post of Head of the Visual Arts Commissions Department until 1999. Since then till 2012 he has been the artistic leader, senior curator and adjunct director of SKOR (Foundation for Art and Public Space).