From Glass to One-Way Glass

Shifting Meanings of Transparency, Openness and Privacy in Architecture

November 18, 2011essay,

Whereas in the 1950s transparency in architecture was considered an unambiguous and politicized ideal, since the advent of the television programme Big Brother it has become a paradoxical concept. ‘What is transparent for the camera is opaque for the resident,’ writes architecture historian Roel Griffioen. Openness and privacy, transparency and opaqueness are intertwined with one another more than ever.

I would say that Bentham was the complement to Rousseau. What in fact was the Rousseauist dream that motivated many of the revolutionaries? It was the dream of a transparent society, visible and legible in each of its parts, the dream of there no longer existing any zones of darkness.

―Michel Foucault

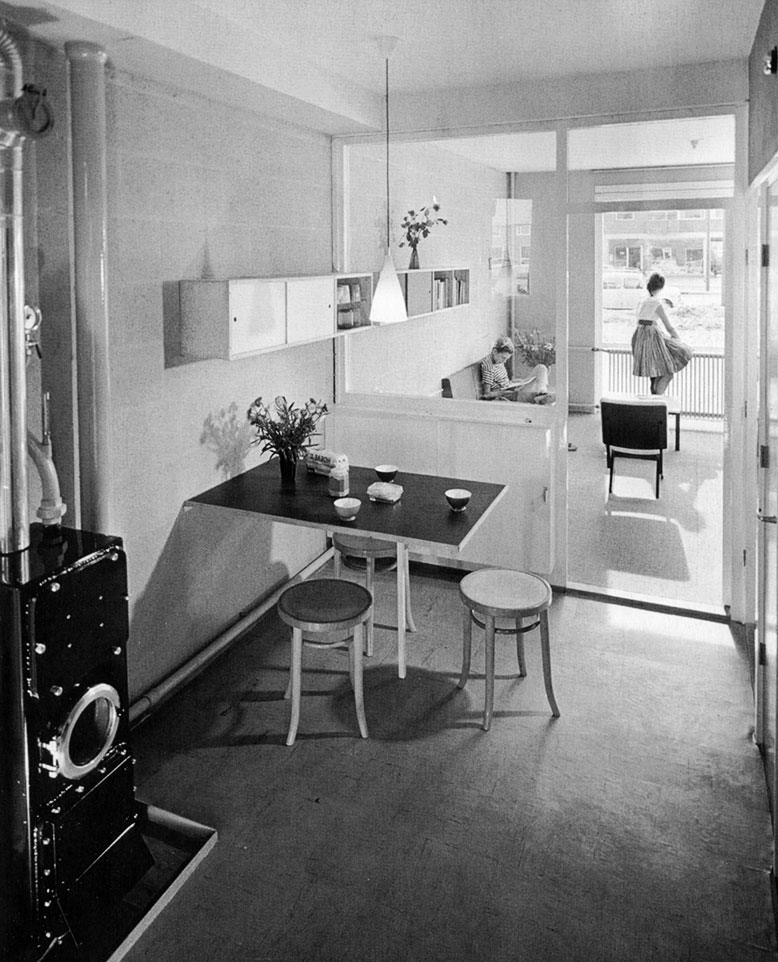

Never to my knowledge has the ideal of transparency in architecture been more clearly represented than by the photographer Jan Versnel. The photographs of residential interiors that he made in the 1950s for the Dutch magazine Goed Wonen (Good Living) are symbols of modern life in an open, lucid home environment. In these interiors there are hardly any strict divisions; rooms are coupled with one another and solid walls replaced as much as possible by glass walls and doors, giving the impression that the space seems to flow from room to room. Light, modern pieces of furniture figure as the visual components of apt compositions evoking pre-war avant-garde painting and photography. Just as there are no thresholds separating the rooms, the private lives of the various members of the household also commingle. In one photograph, the father of the house is doing his paperwork at the dining room table in total concentration while in the same room his daughter attentively watches a repairman fix the radio. On the balcony, her mother chats with a friend.

Jan Versnel’s photographs are not simply photographs; they must be understood as depictions of an educational agenda. The interiors are located in model homes decorated by the Stichting Goed Wonen (Good Living Foundation), an organization set up after the war in the Netherlands by progressive architects, designers, furniture manufacturers and other social reformers who – in their own words – were fighting against ‘tastelessness’ and whose goal was to promote ‘good living for a broadest possible sector of the population’. In a carefully composed mise en scène, replete with props and actors, Versnel depicts what this ‘good living’ entails: living transparently in a transparent house. Family life takes place in the open. The personal worries and cares of individual family members / actors ebb away in the group. All hail to living one’s life in the sight of the Other.

This is what I – in concurrence with the utterances of several post-war reconstruction architects and public housing authorities – would like to call the ideal of the glass house. The glass house in itself was not a concrete building assignment, but as an idealized image of a condition of total openness and total transparency, it is implied in much of the architecture and thinking of the 1950s. Nowadays, this ideal, with its patronizing moral and social connotations, seems utopian and hopelessly naive. The glass house has made way for the much more enigmatic image of the ‘one-way glass’ house, in which concealing has become as important as revealing. On the basis of these two images, I would like to show how concepts such as transparency, openness and privacy have gone adrift over the last half-century.

Transparency as Ideal

The glass house was a bare and empty house, certainly in the eyes of the Dutch in the year 1955. The ideal interiors shown in Versnel’s photographs are – to put it disrespectfully – completely purged. The symbols of Dutch middle-class living, such as massive wooden furniture, heavy carpets, crocheted tablecloths and pleated lampshades have been ruthlessly swept from the scene. In the Good Living doctrine, empty houses would lead to clear minds and clean spirits, just as in Thomas More’s Utopia (1516). In that fictitious realm, there are no ‘occasions of corrupting each other, of getting into corners or forming themselves into parties; all men live in full view, so that all are obliged both to perform their ordinary task and to employ themselves well in their spare hours’.1

Before the war, Walter Benjamin had already opined that modern architecture’s pursuit of light and air would herald the end of the home ‘in the old sense of the word’, that is to say, the home that put ‘security’ in the first place. Benjamin praised the modernist ideal of living in a house of glass as a means of moral self-discipline: ‘To live in a glass house is a revolutionary virtue par excellence. It is also an intoxication, a moral exhibitionism, that we badly need. Discretion concerning one’s own existence, once an aristocratic virtue, has become more and more an affair of petty-bourgeois parvenus.’2 For Benjamin, the ‘old way of living’ was equal to a middle-class mentality and class consciousness. Shelter and protection is desired by people who have a fear of society. In an analogous manner, the constructivist El Lissitzky compared steel to the will of the proletariat and glass to its conscience.

After the war, the supposed social power of architectural transparency acquired an extra pregnant charge. Transparent space acquired the name of being ‘innocent’ space, free of pitfalls and secret places; as such, the bare, spacious floor plans in the 1950s were emblematic for a ‘new beginning’ – in the personal and social sense.3 Several psychologists proposed in the magazine Goed Wonen

This aspiration – the abolishment of the boundary line between family and society – can also be seen in Versnel’s photographs. The windows at front have no curtains and occupy the entire façade. Family life, formerly often imagined as the bastion of intimacy, is totally exposed to society. The outside world is included in the composition, shown as part of the inside world. The buildings on the other side of the street are visible, framed by the window. Lines of perspective that start in the interior of the dwelling continue through the cityscape without juddering to a halt. ‘The home no longer ends at the front door, there to encounter a hostile world,’ wrote architect Willem van Tijen. In its austerity and openness, this modern residential architecture referred to a classless society in which it was unnecessary for individuals to seek seclusion, seeing as in society they would encounter the same warmth and safety that was formerly reserved for the home. The model society itself was thus imagined as a society without walls – a glass house.

Already in the 1950s, however, criticism was mounting against the ideal of the glass house. Urban sociologists complained that such houses offered too little sense of security. These critics sooner associated openness with social control, surveillance and government interference than with autonomy and democracy. Not transparency but its opposite, privacy, was what they associated with freedom – more specifically, ‘the freedom to determine one’s own life’. They felt that the lack of lockable rooms in the house and all that glass would act as a check on the inhabitants’ right to self development. In the critics’ experience, the glass house was in reality a see-through straitjacket.

Nowadays, anyone who walks through an arbitrary redevelopment district in the Netherlands will get the impression that the bankruptcy of the glass-house ideal is definitive. Under the banner of urban renewal, entire neighbourhoods have been torn down and replaced by introverted types of dwellings, housing blocks closed to the outside world and enclave-like ‘residential domains’, islands in the urban fabric. Open housing as an emblem of social transparency has been defeated by the ‘my home is my castle’ ideal, in which the home is the antithesis of society. Privacy is deemed more important than openness. Those who can afford it move into an enclave, shut themselves off from a world that is identified with danger, animosity and inconvenience.

Shifting Meanings

The metaphor of total transparency has always been Janus-faced, with on the one side the promise of freedom, equality and democracy, and on the other the nightmare of totalitarian surveillance and loss of individuality. In the classic dystopias in literature, the ‘public’ aspect imposed by the system is the most important instrument of coercion and disciplining. In the ‘One State’ in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We, the ‘crystallization of life’ has been made the highest objective.4 For the citizens of this dictatorship, who truly live in glass houses, the hour for sex is the only time that the shades can be drawn. In Ayn Rand’s Anthem as well, ‘none among men may be alone, ever and at any time, for this is the great transgression and the root of all evil’.5 So you can roughly say that what symbolizes a kind of paradisiacal condition for the community-minded represents a hell for liberals, who see the citizen as an autonomous subject whose principal right is that of self development.

Yet this classic dichotomy no longer appears tenable. Openness and privacy, visibility and shelter, transparency and opacity are concepts that have begun to shift. The revival of the ‘my home is my castle’ ideal, for example, has not been accompanied by a lessening of surveillance. As paradoxical as it may seem, the increase of privacy requires greater transparency. However, the difference with the glass house model is that this transparency only works in one direction. Camera surveillance, gatekeeper policies and videophones are the most visible indicators of this one-way visibility. More subtle forms are the closed or half-closed residential blocks in which the collective can keep an eye on the semi-public space (the courtyard or inner garden). Supervision does not take place from one central panoptical Eye, but from the totality of all the residents, who can watch over the semi-public space with hundreds of pairs of eyes at once without having to leave the comfortable protection of their own homes.

The ideal of the glass house may be dead and buried, but it has reincarnated in a new form. For lack of a better term, I call this the ‘one-way glass house’. A one-way glass is a material that expresses the blurring of concepts indicated above: it gives the possibility of seeing without being seen. This complexity can be further enriched with the one-way glass house’s prototype, namely the ‘house’ in which the first Big Brother series was filmed in 1999. This is the very picture of openness and transparency, albeit in a totally different way than the modernists had predicted.

It is no exaggeration to state that Big Brother signalled the breakthrough of reality TV in the West. This formula conceived by Endemol was first tried out in the Netherlands and then exported to almost 70 countries. The premiering season was broadcast on Veronica from 16 September to 30 December 1999 (a total of 106 days). The formula was simple. Eight candidates were put into a house, with one person being ‘voted away’ each week, until after about 100 days three participants were left over. From these three, the television audience chose the winner.

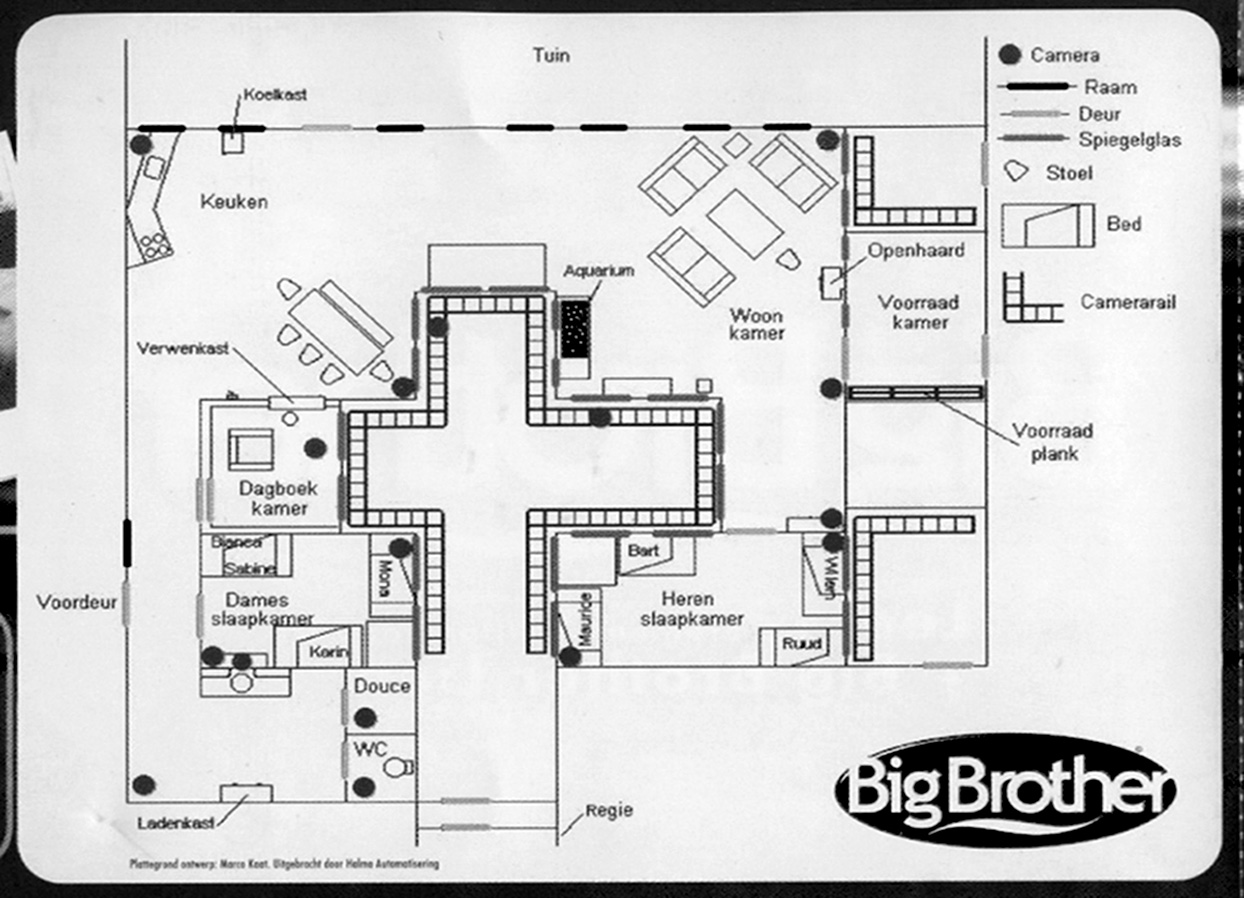

More sensational than this game formula was the fact that the participants were continually filmed throughout their stay and that they were completely closed off from the outside world. All of the ethical, psychological and dramatic aspects of this programme have already been extensively discussed in the literature on the subject, so I would like to limit myself to its ‘architecture’, in other words, the physical setting for the TV formula. The house in which the first season of Big Brother was shot was specially built for that purpose, at the edge of Almere, a location that was chosen because the residents would have the feeling of being ‘on a drilling rig in the ocean’.6 The living quarters comprised a house with 145 m² of floor space and a 260 m² garden. This dwelling, a space that was artificially shuttered but visible to the public via the cameras, was the stage on which the participants engaged in ‘reality’. The space was physically very enclosed, enclave-like, inward looking, but at the same time completely transparent. With 24 fixed cameras, every nook and cranny of this interior was made visible to the television viewer. The layout, the cameras and the interior design formed a unit that could not be dismantled. The participants were not allowed to move the furniture an inch, on penalty of being thrown out. Even the direction in which the participants slept – from the head to the foot of the bed – was especially geared to the camera positions.

Screened off from the field of vision of the participants and the television viewers was an extensive architectural programme that facilitated the interior’s visual transparency. A production unit with 162 m² of floor space – thus larger than the house itself – was built next to the house. A look at the floor plan shows that a secret infrastructure was moulded around the interior revealed by the cameras. Lying in two cross-shaped corridors are rails upon which cameras are ridden past the most important rooms, which are purposely linked to the cross: the living room, the kitchen, a confession room (the diary room) and the two bedrooms. The cameras can look inside through one-way transparent strips – indeed, one-way glass mirrors. What is transparent for the camera is opaque for the residents. The ‘architecture’ built up out of sound and image is completely transparent, while the physical architecture is stratified and mystifying.

The Stimulation of Behaviour

In the topological sense, the Big Brother house is a kind of cuckoo chick in a family in which community spirit is the norm. Of note, for example, is its relation with the communal houses that the Russian constructivists designed during the interwar period, residential complexes in which the possibilities for seclusion were reduced to zero through the architecture. Like the workers in utopian Soviet designs, the residents of Big Brother slept with others in the same room, the men and women apart. Personal possessions were limited – Benjamin’s statements that transparency is the enemy of secrets and property is as applicable to the Big Brother house as it is to the radical residential experiments in Russia. Indeed, the openness was carried even further in the temporary complex in Almere. Even in places where it was possible for the housemates to be alone (in the toilet and shower) the television viewer’s technical eye was present.

For the constructivists, this architectural model was a symbol of ‘social hygiene’, of order and community spirit. For the makers of Big Brother, it embodied the exact opposite. The openness of the house was supposed to function as a catalyser for Big Feelings. The aim of the architecture was not to make individuals lose themselves in the collective, but to splinter the collective into an assembly of individuals. The idea was that when people are so cooped up in an apparatus of boredom and gossip, they eventually must reveal their true nature. When reasonableness is cast aside, the individual emerges. The competitive element of the programme destroys even the most persistent remnants of unity and solidarity. Contrived with the help of weekly assignments prescribed by Big Brother – read: the director’s unit next door – the weekly round of elimination and the televised confession in the diary room was a quick washing machine cycle for hyper-individuality. For this reason, the producers chose a special palette of candidates for the first season in Germany, including ‘a lesbian, a boy with earrings and tattoos, and a girl who works in the telephone sex industry’. The goal, according to the producers: ‘More fights in the house.’7

As is known, Big Brother is named after the tyrannizing System in George Orwell’s 1984 – another dystopia in which openness and transparency are described as methods of suppression. Orwell’s Big Brother uses surveillance as a means of colonizing the individual’s private space and enforcing disciplined behaviour. By contrast, what is stimulated by means of surveillance in the Big Brother programme is abnormal behaviour. The presence of cameras – and thus viewers – titillates the participants’ egos. In the vacuumed interior of the house, their prickled egos run into one another every other minute, resulting in explosions of Big Feelings (love, hate). Their exhibitionism is fed by our voyeurism. Why do we want to peek through the one-way mirror?

Ambiguous

Transparency has lost its clarity as a metaphor. Social theorization can no longer be captured in a crystal-clear architectural image like the glass house. Whereas for political decision-making, WikiLeaks or the financial system, total transparency can still function as an ideal – even though this is increasingly becoming problematical – the storage of telecom information, preventive frisking, camera surveillance and so forth have a decidedly dystopian component. Concepts like openness and privacy – at one time antipodal – have become interchangeable. The houses that we are designing and building today are as far removed as possible from the glass house ideal of the 1950s. We move into an apartment in a brand-new housing block whose façade refers to the crisis architecture of the 1930s, or a monumental building in the classic style of ‘our’ Golden Age, or even better, a closed domain whose inhospitality is emphasized by mettlesome corner turrets with battlements and a veritable moat. In this fort of intimacy, we find diversion by watching people on TV who have voluntarily locked themselves up in public view. Through the television programme Big Brother, we are offered up for consumption a kind of pasteurized version of precisely what we with great difficulty have tried to ban from our own social environment: insecurity, uncertainty, the unknown.8

1. Thomas More, Utopia (1516, English edition by Cassell & Co, 1901, republished in 2008 by www.forgottenbooks.org), 61–62.

2. Walter Benjamin, ‘Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’, in Michael William Jennings, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith (eds.), Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings 1927–1930 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2003), 209.

3. Henri Lefebvre writes: ‘The illusion of transparency goes hand in hand with a view of space as innocent, as free of traps or secret places. Anything hidden or dissimulated – and hence dangerous – is antagonistic to transparency, under whose reign everything can be taken in by a single glance from that mental eye which illuminates whatever it contemplates.’ Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Malden, USA / Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 1991), 28.

4. Yevgeny Zamyatin, We (New York: Harper Collins, 1972), 24.

5. Ayn Rand, Anthem (New York: New American Library, 1976), 12.

6. Rentsje de Gruyter, ‘Op de kaart: Almere’, NRC Handelsblad, 2 December 1999.

7. Jochen van Barschot, ‘Du bist nicht allein. Meer ruzie en meer seks in Duitse versie Big Brother’, NRC Handelsblad, 25 February 2000.

8. Slavoj Žižek brings up interesting and more existential reasons for our penchant for reality TV. He speaks of a tragicomic reversal of the panopticum model, whereby the ‘observed always’ is turned into a positive, perhaps even intoxicating aspect of life. Big Brother and its countless spin-offs and successors are symptoms of this reversal. Žižek even suggests that we meanwhile have all become actors in a reality soap opera, because we live in the awareness of the possibility of a panoptic Eye that follows all of our actions. ‘What if Big Brother was already here, as the (imagined) Gaze for whom I was doing things, whom I tried to impress, to seduce, even when I was alone?’ Slavoj Žižek, ‘Big Brother, or, the Triumph of the Gaze over the Eye’, in: Thomas Levin (ed.), CTRL [SPACE]: Rhetorics of Surveillance from Bentham to Big Brother (Karlsruhe: ZKM, 2002), 224–227.

Roel Griffioen is a writer and researcher. He works at Casco – Office for Art, Design and Theory, is an editor for Kunstlicht, and is currently co-initiating The Front Line, a critical research project examining the role of the creative class in urban politics.