Insecurity by Design

WTC New York

April 7, 2004essay,

The idea that architecture keeps danger out seems a fable since the attacks on the World Trade Center buildings in New York. Therefore, architects should stop pretending architecture offers security and protection. So long as they refuse to see that architecture is not neutral, they will keep on building new targets.

A very tall building absorbs a plane and collapses after 105 defiant minutes, having watched its twin suffer the same fate. Everyone sees it. Again and again. It captures every eye and ear in stunned amazement.

When the towers fell, the world shook. Nobody could accept what they saw. Such a vertical drop seemed impossible. And no amount of analysis of the mechanics of the collapse, the simple way the attack was carried out, or the strategic mission of the attackers can ease the incredulity. The event remains unbelievable, surprising even to those who initiated it.

People turn to architects for answers. Surely those responsible for shaping structures could help explain the meaning of this traumatic event. Emerging from relative obscurity, architects were featured in magazines and extensively quoted in newspapers. They appeared on television talk shows and were interviewed on news broadcasts. It was hard for any designer or critic to remain thoughtfully silent. Yet so little is said in the end. Everyone pretends to find in the event the clearest evidence for what they have been saying all along. Mainly it is a kind of disciplinary therapy, a reassertion of the traditional figure of the architect as the generator of culturally reassuring objects, an ongoing denial of the fact that architects are just as confused as the traumatized people they serve.

Why did our seemingly hyper-aware and congenitally paranoid world become so shocked? Not because of the number of people killed. Such numbers are tragically all too common on a planet routinely tormented by starvation, war, disease, and genocide. Nor is it simply the terrorist assault on a large metropolitan building. Buildings are constantly being targeted. Yet while the front pages of newspapers regularly feature the lethal rubble of flattened modern buildings, none of these collapses has stimulated any kind of debate about architecture. Only with the destruction of the World Trade Center have the designers and critics swarmed down like vultures to pick over the site of collapse, unable to offer much because the ancient intimacy between architecture and violence has for so long been off-limits in their discussion.

A Reassuring Witness

To grasp the event, we need to appreciate the intense fantasies people have about buildings in general and the twins in particular. To begin to understand the depth and complexity of the reaction, we need to go back to the simplest level. In the simplest terms, buildings are seen as a form of protection, an insulation from danger. To be hurt by a building is unacceptable. Even the most minor fragmentation of a structure is front-page news. And fatal collapses are international news – death by architecture is intolerable. Furthermore, buildings are traditionally meant to last much longer than people. It is the sense that buildings outlive us that allows us to have a life.

Buildings shelter life by sustaining a collective sense of time, a form of cultural synchronization. Buildings act as a reassuringly stable witness of whatever we do by surviving longer than us and evolving more slowly.

This sense that our buildings are our witnesses depends on a kind of kinship between body and building. Not only should buildings protect and last longer than bodies, they must be themselves a kind of body: a surrogate body, a superbody with a face, a façade, that watches us. We use buildings to construct an image of what we would like the body to be. Buildings are thereby credited with considerable representational force. This force can be seen in the everyday notion that the place where you live continues to represent you when you are hidden within it, away, asleep or dead. Like your clothes, your building projects some kind of stable image regardless of what you are doing or feeling.

Terrorists know this, have always known this. They play with these basic fantasies about architecture, wounding buildings as often as people. Damaged buildings represent damaged bodies. And it is the representation that counts. Terrorism is not about killing people, but about dispersing the threat of death by producing frightening images. Particular sites are targeted to produce a general unease. If you can identify with the target, then your own buildings become unsafe, and everybody becomes vulnerable. This tactical use of images of assaulted buildings plays with precisely the representational capacity of buildings that architects have devoted themselves to for millennia. In this, the terrorist shares the expertise of the architect. The terrorist mobilizes the whole psychopathology of fears buried beneath the architect’s obsession with efficiency, comfort, and pleasure.

The Humanity of Buildings

The attack on the towers was an extreme yet textbook example. What was unique was the size of the audience and therefore the size of the threat. Symptomatically, the video statement by the structural engineer Osama Bin Laden refers to striking the ‘softest spots’ of America, its ‘greatest buildings’, and not the people within them. The real threat is to the architecture, or rather to an architecture that represents a much wider population than its physical occupants. In a classic sense, the targeted buildings represent the bodies of a global constituency, assuming the humanity of all those who watched. Again and again, the towers are described with the same terms used for suffering people. In the grieving for those who died, there is also grieving for the buildings themselves. In all the improvised memorials and media coverage, images of the towers’ faces share the same space as images of the victims’ faces. The buildings became victims, and in so doing victimize those who watch them suffer.

If everyday cultural life makes an unconscious association between body and building, it is enormously frightening when the confusion becomes literal. The devastating spectacle of September 11 was a simultaneous destruction of body and building and the distinction between them. ‘He became part of the building when it went down’, as one distraught parent lamented. The buildings became lethal elevators, dropping in on themselves at the same speed as any object free falling in the air. No resistance: 415 meters of structure compressed into 20 meters of rubble in 10 seconds, generating a level of energy comparable to nuclear blasts or volcanic activity. Buildings and bodies were instantly compacted into an extraordinarily dense pile or dispersed to the wind. In lieu of remains, family members received small boxes of the dust. The bodies themselves were mainly lost, and even the number of victims stayed a mystery. The few bodies that were found were kept invisible. Despite all the intense and endless media coverage, no bodies were shown. No broken, bloody, burned, or fragmented people. Just the desperate flight of those who could choose to jump, and the shocked, dust-laden bodies of the survivors.

Millions streamed downtown to look, partly driven by the voyeuristic compulsion to see the site of such a huge crash and partly like loving family members of the buildings themselves who needed to see the actual body of the buildings to accept their loss.

Perplexing Popularity

The towers had of course been designed to produce such a global audience. The whole point was for them to rise up above the city at the end of the island facing Europe to capture world attention. Which they did. They were the centrepieces of billions of images. More postcards were sent of the towers than of any other building in the world. And what was constantly looked up at by so many was also looking back. Whether we were on the streets of Manhattan or watching TV in living rooms on the other side of the world, the Twin Towers had an eye on us. But there is now a palpable sense on the island of having lost a crucial witness that could see you wherever you were: an architecture of image that was understood, and enjoyed.

This popularity was never understood by architects, who are now being asked to talk about buildings they never embraced. Indeed, the Twin Towers were mercilessly slammed by architectural critics, particularly those who led the support for so-called ‘postmodern’ architecture. For them, the towers personified the inhumanity of modern architecture. Ironically, the critics spoke in the name of popular sensibility. But in the end ordinary people simply had stronger feelings about the buildings than architects, to whom they rarely listen anyway. The Twin Towers played a much bigger role in everyday experience than in architects’ discussions. At some level, an extraordinary identification with the buildings took place that exceeded the expectations of both the boosters of the project and the architectural critics. Precisely because their brutal scale did not fit into their surroundings, they perfectly belonged in a city of refugees and misfits of every kind, the city that is at once the most and the least American.

The key symbolic role of the World Trade Center, the rationale for both its design and its destruction, was to represent the global marketplace. In a strange way, super-solid, super-visible, super-located buildings stood as a figure for the dematerialized, invisible, placeless market. In this, architecture was surely a vestigial symbolic system, as demonstrated by the fact that the markets reopened within days after the attack. Supposedly fragile digital patterns have long assumed the solidity once associated with buildings. Electronics have taken over from architecture as our primary witnesses and storehouses of collective memory, allowing buildings to assume new roles. Not by chance were those who first described the architectural role of electronics in the 1950s and 1960s also those who insisted that buildings should become as expendable as dishwashers and toasters. Yet the traumatic reaction to the loss of the towers themselves, beyond the terrible loss of life, shows that even the vestigial system of architecture had more force than anyone expected. Still, it is as yet unclear what it means to threaten a building in an electronic age.

Representation

We need to look more closely at exactly how this seemingly outdated representational system worked. The World Trade Center was a hyper-development of the generic postwar corporate office tower. The corporate building provides a fixed visible face for an unfixed, invisible and carnivorous organization. Typically, there is no sign of the company on the building. The lack of a literal sign becomes the sign that the corporation is nothing more than an open network. As is written into the very word, the ‘corporation’ is an abstract body, a corpus composed of many bodies networked together into a single organism. It is an invisible collective network that may be made visible on a particular site by a building.

The shiny glass ‘curtain wall’ is not a showcase revealing the workers inside. During the day, reflections usually render the interior mysterious. At night, when the interior becomes visible, it is the horizontal grid of fluorescent lights visible through the vertical grid of the façade that is put on display, not the workers. The fluorescents, which are never turned off, are more important than the workers. Not by chance is the corporate office building one of the first building types to be routinely photographed at night by architectural publications. Of course, there are internal spaces occupied by workers, and a whole range of tactical design strategies for accommodating them, but this remains subordinate to the polemic of the outer screen. At the ground level, the façade is thinned down to the absolute minimum and the resulting walls of glass invite the eye and body in. But all that is revealed is a huge lobby space that usually continues the pattern and materials of the exterior plaza. What promises to be the interior turns out to be an exterior bathed in eternal artificial sunlight and inhabited only by the elevator core. The elevators are the only substantial objects. If you look up, you don’t see the solid underbelly of the building’s main volume but an artificial sky, a continuous, brightly glowing, horizontal surface that veils even the shape of the fluorescent tubes that activate it. The hidden office floors above often have the same kind of singular glowing ceiling. And even when the fluorescents are discrete fixtures arrayed across an opaque surface, workers do not inhabit rooms but are distributed across a ‘landscape’. In the most fundamentalist sense, the corporate building has no interior.

The Neutral Screen

The Twin Towers took this to the limit, perfecting the logic of the ‘neutral’ screen, stretching it to the clouds and exemplifying the culture of the invisible body. The towers were at once sealed yet porous, intimidatingly heavy yet floating. The twins were at their most beautiful at night as a complex pattern of lights hovering above the city, framed by the sky-lobbies and observation levels which turned into thick dark bands. The lights simulated occupation, but not by people. For the first decade, 23,000 fluorescents always remained at their posts, working around the clock. There were not even light switches in the towers until 1982, when the endless stacked layers of light started to fragment into an elusive and seductive figure.

The two mysterious, gargantuan shafts connected a vast, crowded, horizontal slab of shopping and eating in the ground to equally crowded platforms for viewing, eating, and drinking in the sky. Below the shopping level was a physical communication hub that radiated multiple underground rail systems. Above the viewing level was an electronic communication hub that radiated television, telephone, microwave, and radio. The result was a density of bodies in the spaces of consumption below and above, framed by communication networks binding the structure to the city and the rest of the planet. In the space of production in between, the two shafts, the body simply disappeared. Tourists rocketed through it in America’s largest and fastest elevator, suddenly aware of the inside of their own flesh but oblivious to the spaces and people that surrounded them.

Even the workers did not simply enter or appreciate the space. Isolated in their express elevators, they went to separate sky-lobbies from which they took local elevators to their respective floors. Yet in the deluge of countless images of the building in loving reaction to their unbelievable disappearance, it was symptomatic that not one showed the interior of the workspaces.

The design of these hidden spaces was celebrated in the press as highly innovative when the buildings first went up. The invention of sky-lobbies had freed up an unprecedented amount of usable floor area. Concentrating all the structure into a tight ring of huge columns around the elevator core and another heavy ring around the outside of the building made the workspace column-free. Starting with their own choice of lighting pattern, each of the huge number of tenants could organize their slice freely and differently, setting up a whole array of different relationships to the famous façade, a heterogeneity that was masked by the unified exterior, and only subtly implied by the different intensities and rhythms of the light pattern at night.

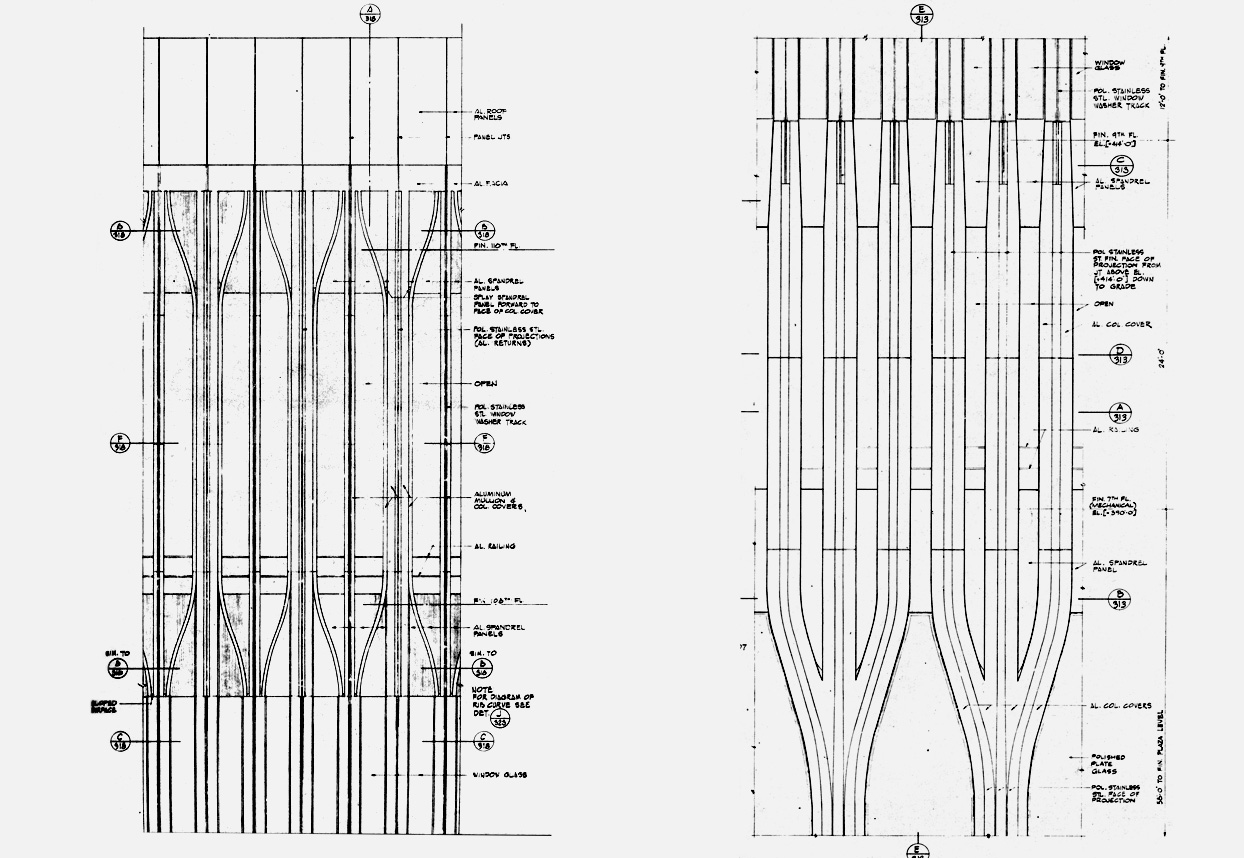

The towers had no front, back, or sides. Each face was the same. Furthermore, the buildings had no depth. There was no simple view of them in perspective. The smaller buildings ringing their base blocked the view upward, and the windswept plaza on top of the shopping mall was typically deserted. The buildings were meant to be seen from a distance, as pure façade. They were made to seem flat, as can be seen in the architect’s original renderings. Each typical view, the cliché embedded in a worldwide consciousness, had two seamless screens side by side: each a shimmering blend of aluminium and glass, subtly modulated by the Gothic- and Arabic-inspired details of the stretched floor heights at the bottom and the top, and the even subtler change of dimension produced by two sky-lobbies. The curved grafting of the columns at the base could be read from a distance, but the details in the higher floors were so discrete that only their effect was visible, and then only just. Setting the glass back in the recesses between the huge columns meant that the colours and texture of the face changed continuously with each new angle of view or sun – a minimalist composition that achieved a maximum array of effects.

The Twin Towers were a pure, uninhabited image floating above the city, an image forever above the horizon, in some kind of sublime excess, defying our capacity to understand it. The unfathomable trauma of their destruction simply deepened the mystery. And despite the earthshaking intensity of the collapse, the dust finally settled to reveal large sections of the façade improbably left standing, the whole spirit of the building encapsulated in a lonely porous screen whose subtly grafted curves may well have become the most famous architectural detail in history.

Haste

The eventual demolition of this poignantly defiant screen was itself foolish and painful. There was an obscene haste to remove all the traces and rebuild in a desperate attempt to fill the void in so many hearts and bank accounts. But the question of how to replace nine million square feet office of space is irrelevant. If anything, the issue is how to replace the more than two million square feet of façade – those vast, uncannily duplicated screens. When the facades came down, the faces of the invisible occupants who were lost came up, filling the vertical surfaces of the city in pasted photocopies and covering the surfaces of televisions, computers and newspapers all around the world. They formed a new kind of façade, a dispersed image of diversity in place of the singular monolithic screen. In contrast, survivors were covered with dust, all differences between them concealed by a uniform coating, screened by a thin layer of the building. The old façade still at work. It was precisely those who were missing, those the buildings did not protect, who had their horrifying disappearance marked by a sudden visibility. When architecture rises again, it will probably rebury what was exposed. Another defensive screen will be placed between us and our fears.

This new screen, even, if not especially, that part of it devoted to ‘memorial’, will insulate us from what happened. A city that was able to so completely forget that a third of it was destroyed by a deadly downtown fire in 1776 (‘a scene of horror beyond description’ said the newspaper of the day) and forget that a quarter of it (700 buildings) was destroyed by another downtown fire in 1835, will be able to forget this latest trauma remarkably quickly. The whole financial district that acted as the site of the latest catastrophe was itself entirely built within a year of the 1835 fire – the first architect having been hired only a day after the fires were put out. Surely a city shaped only by greed will once again find ways to profit quickly from its pain. Appeals to memory and solidarity will be but excuses for multiple forms of local and global restructuring. New shapes of building and social control are easily promoted in the guise of healing the physical and psychological wounds.

The Illusion of Security

Before any such talk about rebuilding, there should have been a patient attempt simply to understand exactly what happened. After all, what occurred is not simply the tragic loss that we can point to, no matter how dramatic and clear-cut it seems. Nothing was easier to point to than the Twin Towers and their collapse. Yet amidst the obvious horror, there is another level of trauma that is even more challenging because we are unwilling to acknowledge it, let alone comprehend it. For what might be really horrifying in the end is precisely what was already there. The collective sense that everything changed that morning may have more to do with no longer being able to repress certain aspects of contemporary life. Things that we have been living with for some time were disturbingly revealed. The everyday idea that architecture keeps the danger out was exposed as a fantasy. Violence is never a distant thing. Security is never more than a fragile illusion. Buildings are much stranger than we are willing to admit. They are tied to the economy of violence rather than simply a protection from it.

When the design of the twins was first revealed in 1964, the architect said that they would be a physical manifestation of ‘the relationship between world trade and world peace’. Did we really think that the emergent forces of globalization were so innocent, and that architecture could embody that innocence? Did we really think that buildings could be in any way neutral? Or did we just agree to pretend? The rationalizations of the rebuilding are just as naïve – and just as successful. Once again, business will appear to be separated from memory, a clear prophylactic line will be drawn between ‘memorial’ and routine industrialized spaces for offices, shops or residences. We will again pretend to understand the structures we occupy and observe. The only challenge will be to select the collective forms of denial. And in burying our fears so earnestly, we also bury our pleasures. Architecture will be neutralized and returned to the background.

Architects are in fact filled with doubt, and often share it when they passionately discuss their designs amongst themselves, but they are called on to exude confidence in public. If our buildings are meant to give us confidence, their producers apparently have to embody it. But if architects are not used to bringing their doubts about the status of buildings into public discourse, they are unable to contribute to the much-needed discussion of architecture’s intimate and complex relationship to trauma. All they can do is once again collaborate on the production of images of security, comfort, and memory. The embarrassing truth is that the traditional architect is empowered rather than challenged by such events. Architects are in the threat management business. For all their occasional talk about experimentation, they are devoted to the mythology of psychological closure. But the only architecture that might resist the threat of the terrorist is one that already captures the fragility and strangeness of our bodies and identities, an architecture of vulnerability, sensitivity, and perversity. Ignoring this, architects will unwittingly get on with the job of making the next targets.

This text is a version, specially adapted for Open, of a text previously published in: Michael Sorkin, Sharon Zukin (eds.), After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, Routledge, New York 2002.