Architecture in Control Societies

Security as a Selling Point

April 7, 2004essay,

As city authorities are confining themselves to their basic tasks and citizens are compelled to take the care of their living environment into their own hands, ‘gated communities’ like those becoming increasingly common in the United States may not be far off for the Netherlands, according to Harm Tilman. The development of a society of control in which the issue of security is high on the political agenda has opened the way for this in the Netherlands.

Your problem and everyone’s problem in this village is that you think you have a right to be safe. You all know each other, and you’re always telling each other everything. You all went to the same school and you shop in the same shops, and you know each other’s parents and grandparents and great-grandparents. You all arrange everything among yourselves. You think that because you go to school, and to your work, and pay your taxes and don’t break the law too blatantly, nothing can happen to you. And when something does happen, you’re outraged. And then a scapegoat has to be found. It’s time you woke up, Tessa. Just because you shower every day doesn’t mean you can’t get dirty.1

Your problem and everyone’s problem in this village is that you think you have a right to be safe. You all know each other, and you’re always telling each other everything. You all went to the same school and you shop in the same shops, and you know each other’s parents and grandparents and great-grandparents. You all arrange everything among yourselves. You think that because you go to school, and to your work, and pay your taxes and don’t break the law too blatantly, nothing can happen to you. And when something does happen, you’re outraged. And then a scapegoat has to be found. It’s time you woke up, Tessa. Just because you shower every day doesn’t mean you can’t get dirty. Not long ago, a village near the city where I live was shaken by the brutal murder of a petrol station owner. The loot totalled 100 euros and a few packets of cigarettes. The young perpetrators turned out to live around the corner and were quickly apprehended. A week and a half later, the village turned out for a silent march, yet another protest against random violence in the public space. It was not the first and probably not the last demonstration against reprehensible behaviour in public. They express a ‘high level of common anger against the presumed and actual causes of evil’ and constitute an escape valve for a society that is no longer what it was.

In the recent book Sferen (‘Spheres’) the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk analyses various forms of anger in solidarity.2 Sloterdijk argues that these are partly represented in scandals and expressions of indignation. This can even include the collective fuss about a former Amsterdam city alderman’s visit to the prostitution zone on the Theemsweg. These are exercises that are meant to banish evil from our midst. Together they define a communal inner space that can be called secure. The two processes are closely connected. Sloterdijk sees these efforts as attempts to create a safe distance between the immune space of the group and its banished spoilers. Security is a necessary ingredient for a society that has become highly individualized.

Societies of Control

The current growing focus on security or insecurity coincides with the transition from a disciplinary society into a society of control, as analysed two decades ago by the French philosopher Michel Foucault. The former type of society reached its high point at the beginning of the twentieth century. A characteristic of this is that the individual moves between closed environments, each with its own patterns, which succeed each other in a set order, from the family to the school, the military barracks, the factory, the hospital, the prison and the retirement home. In Foucault’s view these environments slowly became mired in deep crisis. Well-intentioned but ineffective reforms are an expression of this. The school system in the Netherlands, for example, has been radically transformed various times since the implementation of educational-reform legislation in 1968, with little result.

The considerations developed by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben in the book Homo Sacer outline the consequences of the emergence of a society entirely based on control.3 According to Agamben the distinction between biological life (zoe) and the qualified life of the citizen (bios) have disappeared, and all that is left is bare existence. Therefore it is no longer the city, but the camp in which life can be controlled down to the smallest detail, that forms the paradigm of contemporary politics. The camp has embedded itself firmly in the city, according to Agamben. At airports and stations, in shopping centres and asylum centres, a state of emergency is increasingly in force. Such ‘non-places’ are the epitome of modern camps, Agamben says. ‘In all these cases an ostensibly secure place actually marks off (…) a space in which the normal order has effectively been suspended and the extent to which outrages are committed depends not on law, but only on the decency and morality of the police temporarily exercising sovereignty.’

A new urban reality is emerging. According to Paul Virilio, cities are being turned inside out, with sections of the public space becoming private and the private space becoming more public.4 The design of the urban space is having to deal with demands for social safety. Insecurity is no longer confined to known bad neighbourhoods; it can be experienced anywhere and at unexpected moments. Conversely, the home, under the influence of the media, the computer and global communication, is turning into an increasingly public space. The traditional opposition of valuable public space versus secure private space has lost some of its importance. The sociologist Ioan Davies makes this clear using the example of the prison.5 In prison there is no distinction between inhabitable and hostile space, as introduced by the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. This space is both familiar and insecure.

Therefore, Davies argues, the use to which a space is put should be made into the starting point. The public domain (the prison) dictates the private domain (the personal everyday meaning) only superficially. In the spatial organization of the public domain, however, the centripetal and the centrifugal coexist, making its entrances and exits coincidental. This means that all spaces are insecure and therefore in one way or another hostile. We can see this reflected in the behaviour of urban dwellers in the public space. People make a detour if they do not trust a situation, or come to arrangements with neighbours and friends, for instance. ‘Space is imagined, put into place, and resisted. The meaning and use of space are everywhere subject to strategic negotiation.’

The Netherlands is Slowly Being Secured

The promotional campaign ‘Nederland veilig’ (‘Netherlands secure’), a joint initiative of the ministries of Justice and of the Interior and Kingdom Relations aptly plays into this. In it, the government is making it known that security is important for everyone. Exasperation about robberies, violence, vandalism and intimidation has reached unacceptable levels, as well as the resulting damage, according to the promotional message. By 2006, crime in and around contemporary non-places, such as stations, parking garages and shopping centres, must be reduced by a quarter. More police officers and more security personnel must ensure more security in the streets, as must surveillance cameras. Citizens are also being marshalled into the effort ‘toward a safer society’. Official certifications, ‘neighbourhood watch’ projects and informant telephone numbers, including the option of reporting crimes anonymously, offer diverse possibilities.

Security is saturating the micro as well as the macro sphere. The official police certification ‘Politiekeurmerk Veilig Wonen’ on house security is intended for owners and tenants of existing dwellings as well as new-build houses and flats. By bringing the dwelling into line with the standards of this certification, residents can be one step ahead of burglars. To achieve this they must adapt their windows and doors and change the locks on the front door and windows, to make them more difficult to force. They are also urged to change their behaviour by locking their doors at night, keeping their keys safe, shutting windows at night and making arrangements with neighbours. All of these measures are meant to result in a higher level of security in the home. This idea was derived from ‘Secured by Design’ in England. New-build dwellings that meet the security standards are granted a certification. In England this proved an effective concept, by reducing the chances for home invasion and turning out to be a selling point for potential house buyers.

But the security policy is now extending to the urban level. In Rotterdam, the city executive has developed an action programme intended to put an end to the deterioration of so-called disadvantaged neighbourhoods. According to the city authorities, these include those areas where too many poor, low-skilled people are settling and which too many well-off, highly skilled people are leaving. This is said to be placing a heavy burden on facilities as well as resulting in a concentration of poverty, nuisance and illegal activity. Key elements of the action programme are stringent residency requirements (such as the requirement that people moving in earn at least 120 percent of the minimum wage), strong-arm measures against illegal tenants and dodgy landlords, allocation of housing in problem areas through positive balloting and the establishment of economic development zones in which private parties receive tax benefits in return for investments.

The growing emphasis on security is also reflected in the use of security impact reports, comparable to environmental impact reports. These are tests on social safety for construction plans and urban projects. According to Tobias Woldendorp, social safety design consultant with Van Dijk, Van Soomeren and Partners, the design of a sustainable city falls within the jurisdiction of urban planners, architects and landscape architects. If the latter neglect security and liveability, a defensive-looking environment emerges, in which the degradation of the public domain can only be turned back through ad hoc interventions. Woldendorp therefore calls for every step in the planning process – from the Document on Basic Principles to the Definitive Design – to include a brief security test. He also wants to link a bottom-up approach to security improvement. The revitalization of city centres and neighbourhoods after all requires the participation of residents.

Toward an Ecology of Fear

The character of the city is changing. During the riots in the black ghettos in American cities, the mayor of Philadelphia observed that ‘from now on, state borders go through cities’. The obsession with social safety and with the guarding of these societal boundaries is part of the ‘zeitgeist’ of urban restructuring. One no longer enters a city via a station or a boulevard. Residents and visitors are now subject to systems of permanent surveillance. This phenomenon is particular prevalent in American cities, where one third of all suburbs are enclosed by security walls. St. Andres, for instance, a ‘gated community’ in Boca Raton, Florida, spends more than one million dollars a year on surveillance. Anti-terrorist barriers in the road surface are beginning to be part of the standard equipment of American residential communities. The obsession with security is greatest in Los Angeles, the city of freedom. Insecurity is not only related to vandals and street gangs, but also with the significant segregation that now characterizes the city.

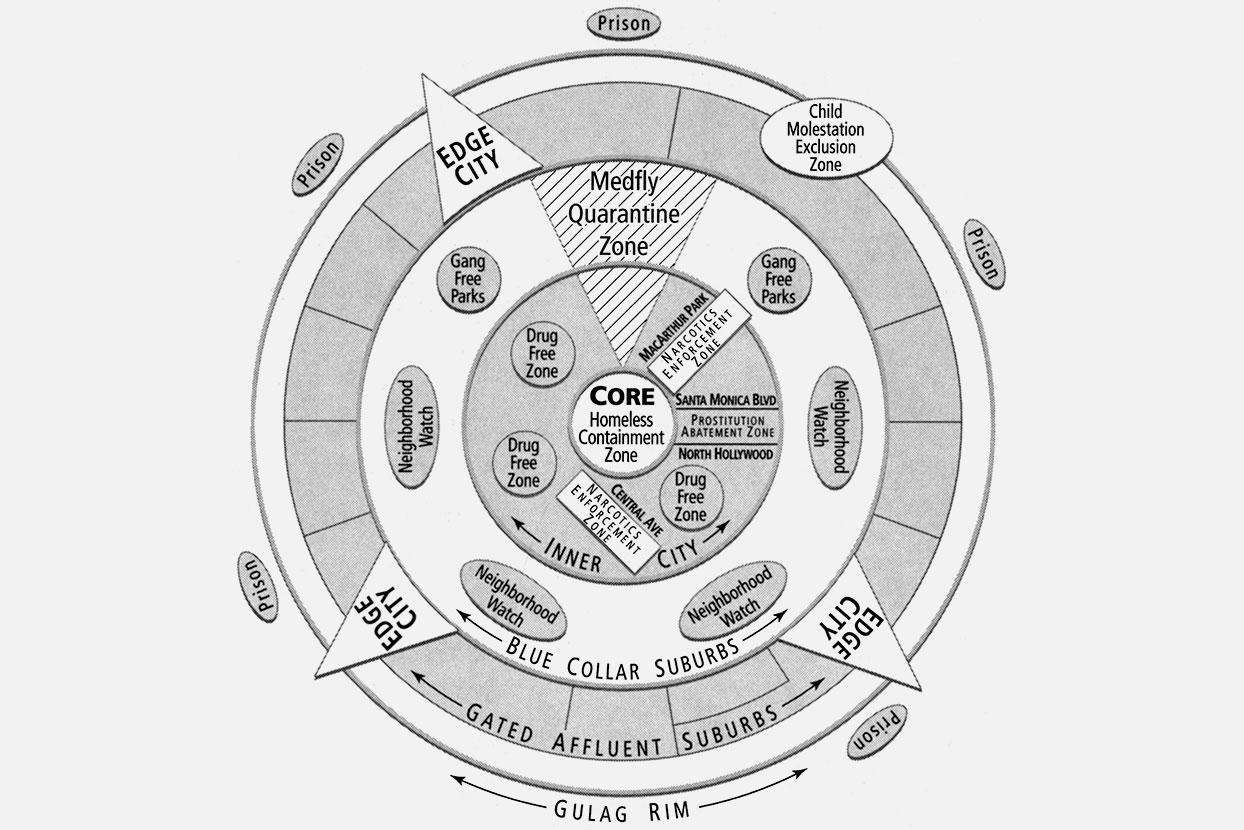

Mike Davis, author of the book City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990), has aptly characterized this phenomenon in ‘the ecology of fear’.6 Davis based this on the diagram used by the sociologist Ernest Burgess to represent the urban dynamics of Chicago in the 1920s. Around the Loop, Burgess drew concentric zones where processes of invasion and displacement were operating. Accessibility and property value are determinants in this scenario. Davis adds the factor of fear to this diagram. The Loop has evolved into a ‘core’ within which undesirables are placed in ‘homeless containment zones’. The inner city, in the Chicago of the 1920s a ‘melting pot’, is now a disadvantaged area in which the police systematically scour alternating ‘drug-free zones’ for set periods of time. This core is ringed by the ‘blue-collar suburbs’, where citizens provide for their own security by means of ‘neighbourhood watch’ programmes. Further out are the ‘gated affluent suburbs’. In the periphery of this city, there are various opportunities for containing minorities within various ghettos.

As far back as the 1980s, Hollywood films, such as Running Man, Blade Runner, Die Hard and Colours, showed to what extent the theme of security had displaced that of social integration. Security is what the economist Fred Hirsch calls a ‘positional good’,7 a good defined by the extent to which people have access to private ‘protective services’ and secured residential enclaves. Moreover, social safety is a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the sociologist William H. Whyte once said, ‘Fear proves itself’.8 We can see this in the Netherlands as well. Although the statistics have not changed dramatically, the suddenly increased perception of threat is dictating the measures now being taken in the area of social safety. The military phraseology used makes references to potential violence and alludes to imaginary dangers.

The Design of New Collectivism

This places repairs to the most intimate of spaces high on the agenda. This is coupled, as made clear by Sloterdijk, with an expansion of the private sphere. This is also happening in the Netherlands. Does this mean that the Netherlands, like the United States, will see ‘defended neighbourhoods’ and ‘gated affluent communities’? The question is not whether, but rather how this phenomenon will manifest itself in the Netherlands. The Dutch housing market has changed from a supply into a demand market, and security is an important ‘positional good’ in this market. This will also find expression in design.

The role of security is different on the outskirts of cities than within existing cities. Individual subdivisions in Vinex developments distinguish themselves through great physical and cultural homogeneity. This is reinforced by the name or metaphor which lends the subdivision its own identity. This allows these subdivisions to exude a strong sense of unity, which gives ‘undesirable visitors’ the impression that they do not belong here. The villa subdivision Park Boswijk in the Vinex development of Ypenburg, for example, stands entirely alone. It has its own identity, primarily one of luxury. The high prices that must be paid for the parcels and dwellings do the rest. Haverleij, near Den Bosch, goes a step further. It consists of islands of luxury dwellings in an attractively designed landscape. Here, cultural homogeneity has also been physically expressed, in that the ‘manors’ are walled in.

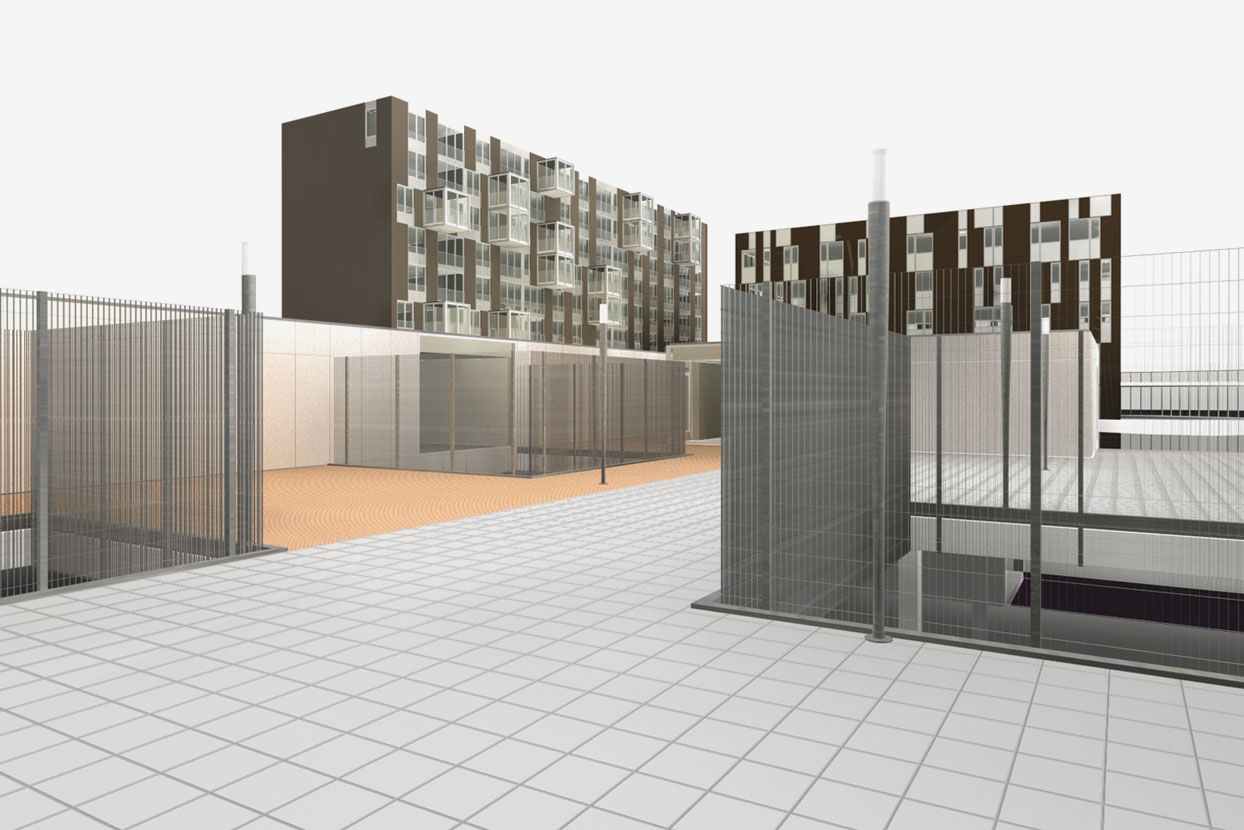

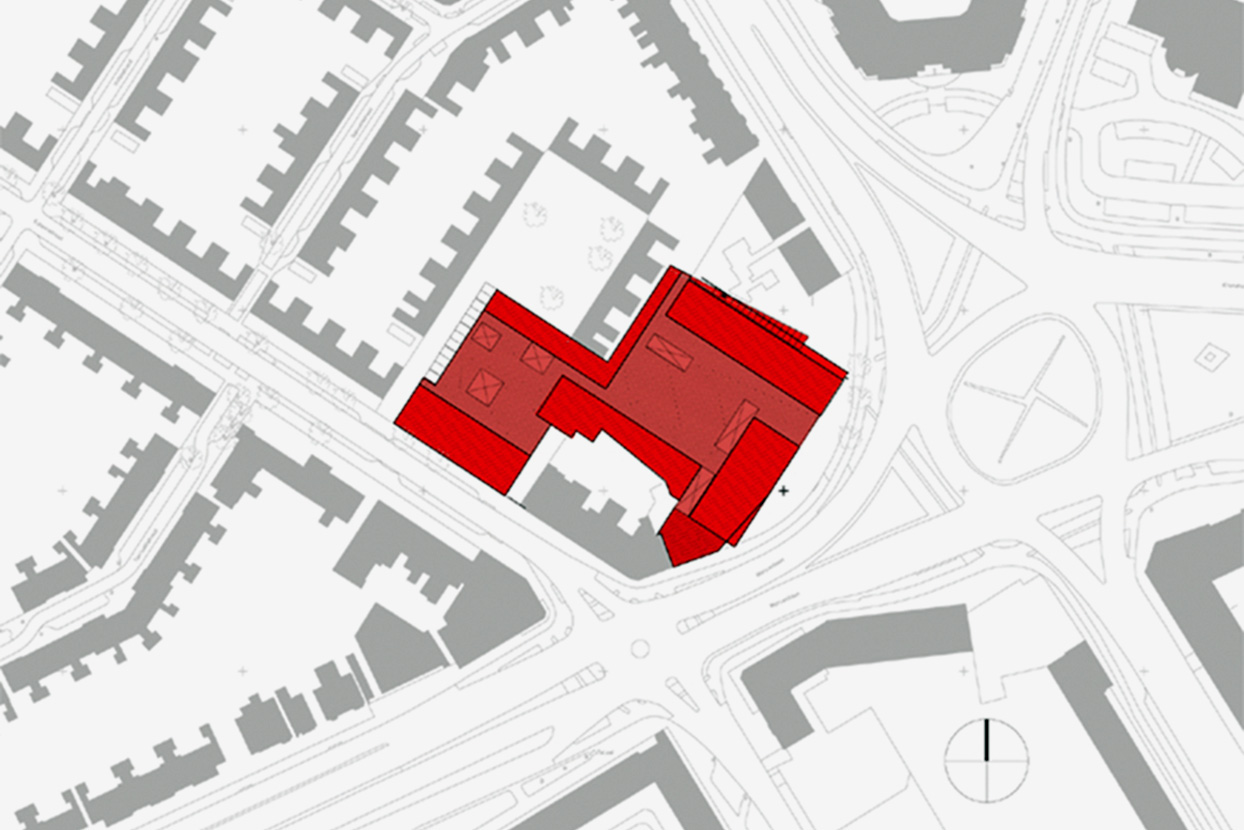

In inner cities, large, ‘thick’ buildings are being created, which can be closed off entirely and offer residents a sense of safety and security. The core here is a collective (or semi-public) space that functions as an inner world within the complex and forms the link between dwelling and city. This collective space provides a controlled oasis or resting place within the dynamics of the big city. It is usually designed as an inner garden, but it can also be a swimming pool or a tennis court. Spectacular examples of this form of housing include the building by Neutelings Riedijk Architecten on the Mullerpier in Rotterdam, KCAP’s ‘Commissaris’ in Venlo and the Baekelandplein project by Paul Diederen of Diederen, Dirrix van Wylick Architecten in Eindhoven. These complexes offer the target group of senior citizens the quality of a ‘protected community’ within an urban environment.

There are as yet no ‘gated affluent communities’ in the Netherlands. In such a community the neighbourhood or the building is enclosed by walls and the area within the walls is fully private (and thus not semi-public). The residents themselves are responsible for the arrangement and maintenance of their domain. Life is subject to strict rules of behaviour, which must be accepted upon purchase. Municipal democracy has been eliminated in these enclaves. It has not come this far in the Netherlands yet. Even when neighbourhoods are walled in, they are not closed off. Yet we are moving in that direction, as municipal authorities are limiting themselves to their ‘core activities’ and citizens have to care for their own living environment. Thus we will not have to wait long for this phenomenon.

1. Kristien Hemmerechts, Donderdagmiddag. Halfvier, Atlas, Amsterdam / Antwerp 2002.

2. Peter Sloterdijk, Sferen, II. Globes, macrosferologie, Boom, Amsterdam 2003.

3. Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer. De soevereine macht en het naakte leven, translation by Ineke van der Burg, Boom / Parrèsia, Amsterdam 2002.

4. Paul Virilio, L’espace critique: Essai, Christian Bourgeois Éditeur, Paris 1984.

5. Ioan Davies, Writers in Prison, Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1990.

6. Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, New York 1998.

7. Fred Hirsch, Social Limits to Growth, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London / Henley 1977.

8. William H. Whyte, The City, Rediscovering the Center, Doubleday, New York 1988.