#Me, #I, #Selfie

The Seduction of Protest Selfies

August 30, 2015artist contribution,

Hu Wei's image essay is part of the Open! Co-Op Academy research theme “did you feel it?” It focuses on the production, distribution and perception of selfies related to Hong Kong Occupy Central. Wei here attempts to understand the role of affect in the functioning of these images: How can protest selfies also be “entertaining” and vice versa?

Sharing selfies has become a global phenomenon given the widespread popularity of smartphones and the social networks to which they provide access. These devices and networks – Instagram in particular – have enabled people to capture and share photographs with friends and strangers continuously: users can update their statuses rapidly and visually. According to statistics, Instagram’s user growth rate has far exceeded Facebook’s and Twitter’s in the past two years, and there are approximately 70 million photographs labeled with #me, #selfie and #I.1

In the Netherlands, on 28 September 2014, I received the news that Instagram had been blocked in mainland China due to the eruption of the Hong Kong Occupy Central with Love and Peace movement. Meanwhile, a huge number of images labelled with hashtags like “Occupy Central” or “Hong Kong Protest” had been shared across the globe via Instagram.2 When Marshall McLuhan asserted that “the medium is the message,” he took the railway as an example: “the railway did not introduce movement or transportation or rail or road into human society, but it accelerated and enlarged the scale of previous human functions, creating totally new kinds of cities and new kinds of work and leisure.”3 In a similar way, Instagram does not change the content and nature of images, but it has changed the way of spreading images and interactions between humans and images, providing a new territory to view and feel an event. It shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action.4 With the global recreational network, a virtual community was formed immediately, where both protestors and tourists respectively share their information and their protest selfies.

I selected and compared various “entertaining” protest selfies that are related to the Occupy Central movement in Hong Kong from different Instagram accounts, talking about the combination between protest selfies (touristic) and the fantasy of being a part of the movement on social media (mainly on Instagram). How do these create emotions in real viewers through cyberspace? And how do they affect the viewers’ experiences? I also question why and how some of the selfies are able to be more affective by analyzing the affect of anonymity versus recognition.

A friend of mine, wearing a Guy Fawkes mask, stands in front of flyovers in the centre of Hong Kong. I noticed this photograph while I was browsing the social media page on my smartphone. Documenting the crowds and banners at the back, he was at the centre of the Occupy Central movement. Instead of using labels and tags related to Occupy Central or Hong Kong Protest, he, as a sort of tease, tagged the photograph with “I thought you would not see me ~,” which alluded to the blocking of numerous social networks by the Chinese government.

Sliding my index finger and thumb continually to magnify the photograph on the touch screen of my smartphone, I attempted to decipher what his hidden face was expressing through the holes in the mask. However, due to the quality and compression of the image, it became even more blurred and pixelated. I noticed that he was carrying at least three image-capturing devices at the same time. A black Canon digital camera is clutched in his right hand; I could determine from this gesture that he uses of it regularly. It looks like he has just taken a shot, or is about to take one. On the left side of his chest, a tiny GoPro HD camera is pinned to the strap of his bag and is probably left to film continuously. The third device is his smartphone, used by a passerby or friend behind the lens, to take this snapshot.

Apparently, the capturing of this photograph has been staged in a certain way. However, the image itself baffles me a little. It might be the disparities between visual sense and imagination, as I realized that the effect it reveals is contradictory to what the photographed subject intended as one of the protestors. It seems that the format of the image is in-between a regular self-portrait and a selfie. On the one hand, the photographer adopts an eye-level composition and the photographed subject did not position himself within the dense crowd behind him. We can see that he also keeps a certain distance from the protestors on the right side of the image. Perhaps, he deliberately tried to get out from the jumbled crowds so that he was able to visually highlight himself better in the photograph. It seems that he wanted to be regarded as an individual here. But what makes it inconsistent is that he is supposed to engage with this Occupy Central movement, wearing his exquisite Guy Fawkes mask, we can easily recognize that he wants to be a participant in the event. Somehow the way my friend had himself photographed kept on confusing me. Then I realized that it had been quite some time since I had seen these kinds of images during my daily usage of social networks like Instagram. Somehow, the style of my friend’s photograph is sort of anachronistic, it reminds me of the old-fashioned mode of taking self-portraits, albeit within the past few years. There are still quite a number of similar ones on Instagram.

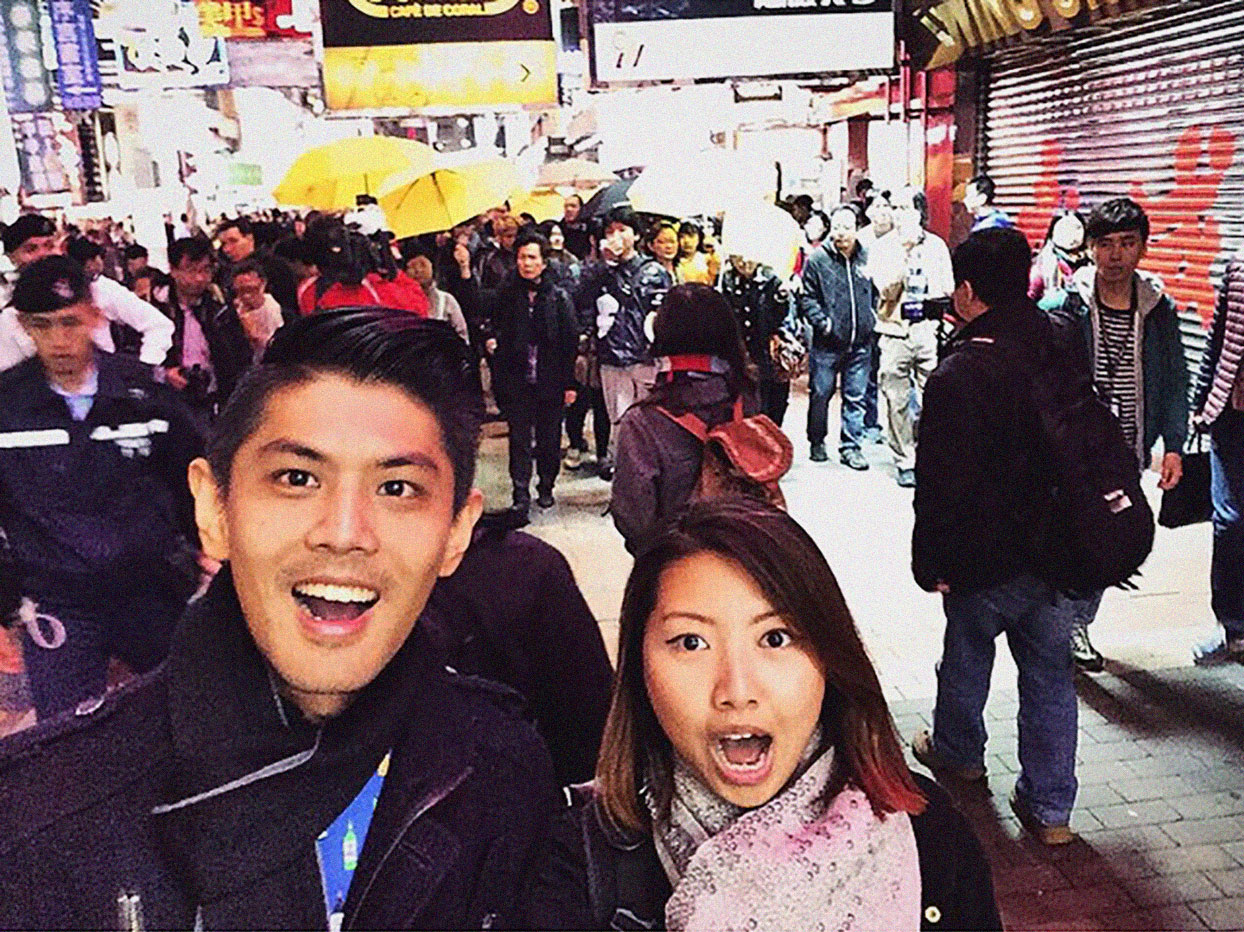

My friend was photographed in the style of a tourist’s self-portait, something extremely popular and common five years ago. These types of photographs tend to adopt a full-length or bust composition, eye-level camera perspective, and stiff and repetitive expressions. The sense of ritual or touristic commemoration seems to work toward proving one’s identity. Waiting, sometimes for a long period, for the photographer to press the shutter button is always an awkward experience. In addition, these kinds of photographs were normally sealed in family albums, kept as private framed photos or on computer hard drives, basically they are shared in gatherings between family or friends. Nowadays, less and less people will show physical photographs and patiently talk about the stories behind them. Sharing pictures has become a virtual and digital experience, with smartphones and social networks increasingly being the spaces for close connections. The reportage that used images from the global Occupy movements for example, demonstrate this virtual participation, which relates to this fantasy of being a part of a political movement, and is synchronous with the ability of these kind of photographs to grasp more attention in cyberspace.

This is another reason for Instagram being used so broadly: from images captured via portable smartphone cameras, image compression and editing tools, simplified keywords and hashtags, to transmitting images onto social networks via the smartphone’s built-in apps, it all operates like a “production line of images” that can be carried out within just a few seconds. Users let everyone know that they are at the scene there and then, and that they are fully engaged in the spectacle. It is like an announcement: “My pictures show that I can and I dare to participate, my photographs are the best proof of this and my intentions.” Yet, the question is whether the demonstrable presence is able to demonstrate participation? The answer is probably no. The subjects being photographed all hold the most demonstrable positions in the first three photographs. However, this recognition turns out to be a form of isolation.

We can look at another photograph which uses the Guy Fawkes mask and compare this with the first one. It was found through a hashtag search on Instagram. Similar crowds, the flyovers in the distance and the same shooting angle, but the photographed person is a little further back, closer to the crowds seen at a distance in the first image. This strategy naturally puts him in a surrounded condition that promotes a much stronger affinity with the parades, and protestors. I noticed that the person photographed is actually facing toward the protest. Originally I had wondered why he was the only person in the crowed to have turned to face the photographer. What it really means is that the Guy Fawkes mask is worn the wrong way around, on the back of the head. I started to reconsider the relationship between the photographer and the publisher of the picture, as well as that between the photographed subject and the publisher. Interestingly enough, staring at the photograph in the beginning, I unintentionally assumed that the photographed subject was himself the publisher. Even though I do not know who the person is at all, the image itself stimulates me much more with concerns about what is happening to the person at the scene, in comparison with the first Guy Fawkes photograph. This concern directly inspires a sensitive affinity between viewers and publisher in a virtual space.

Instagram – the virtual space becomes an interface that immediately connects the actual bodies with digital bodies. This fast and close connection opens the capacity of actual bodies to absorbing various affects. In addition, the responses and attentions, which are from actual bodies, endow the digital bodies and images with more information and messages. Yet the publisher could also be the photographer, which means that the publisher does not know the photographed subject at all. The photographed subject is exploited by the publisher. Thus, the concern of authorship in this photograph seems to no longer be a vital problem. As the fundamental issue has been turned into a statement that “Guy Fawkes is me,” the publisher. When viewers look at the image they see, at the same moment, the Instagram profile image in the top left corner. In this case the profile picture directly corresponds with the actual image. The publisher has become the avatar of the photographed subject. It is easy to notice from the profile and username that the publisher does not over-emphasize this recognition. Browsing through the pictures on this Instagram profile, you can find that the publisher is operating more like a journalist here, and treating the material garnered from the protest in a style reminiscent of news media. The affect of this expression of anonymity is completely different from the previous ones. The publisher and viewers are not in the same space, not directly connected. The publisher is a body without an image, however the body without an image is relatively open to another space, where it can receive the responses not just from people they are familiar with. The affective degree of capacity is bound to each individual who has the fantasy of participation. In a way, the real physical face hidden in the dark is the testimony of the publisher being part of the intensity of the movement.

However, the face of Guy Fawkes is a fairly ubiquitous icon in protests and political movements after all. “Showing faces,” a kind of narcissistic desire and entertainment of psychological demands, it is also gradually extending into more significant fields, through its ubiquity in daily life, either by taking selfies with celebrities, politicians, or political activists. According to various surveys, Hong Kong’s tourism increased by 12.6% and was boosted by the Occupy Central movement.5 Whilst, in a news report titled “Chinese Tourists Are Taking Hong Kong Protest Selfies,” a mainland Chinese tourist mentioned that he wanted to see what it is like, that he had never seen civil disobedience practiced in real life.6 Posing for protest selfies on social networks is not only the embodiment of self-awareness, or the expression of a political standpoint, but also a self-branding tactic. These selfies can, in particular cases, help their publishers get many more “likes” and followers.

Two sets of photographs above (images 6, 7, 8 and 9) have a similar shooting strategy. The key point here is whether the act of shooting is happening simultaneously with the protest, i.e., in the same space and time. We can see from the first set that the person photographed deliberately selects the venues where the conflicts are occurring. Policemen, jumbled crowds and trapped protestors are all rather obvious in the images, but the photographed person (photographer) has separated themselves from the incident. At the moment they pressed the shutter-release button, they became a passerby, or even a tourist. However, in the second set of images, the movement of people is toward the lens, implying that something invisible is happening outside of the photographic frame, that things are happening in front of the photographed (photographers). So these unseen incidents, that cannot be verified, help the photographed (photographers) to create an illusion that “I am at the forefront of the protest and ready to follow it.” Even though the two sets of photographs were both made with the same compositions, expressions and purpose for entertainment, the two photographs (8 and 9) spontaneously extend the intensity of the incidents, smoothly and efficiently into a cyberspace where viewers can feel it, albeit indirectly. The degree of affect of these two photographs tends toward a bodily intensity and its present futurity.

Returning to the very first Guy Fawkes mask photograph, it has exactly the same intention as all the selfies on social networks, which is to announce to all their viewers: “I’m here particularly for this.” Unfortunately, the photograph itself objectively reveals that the photographed subject is engaged with the scene in a much more tourist-like way.

Therefore, how do these entertaining selfies generate an “affective resonance”? From my point of view, compared to the general selfies we take everyday, participation plays a crucial role in protest selfies. For those “participants” who go to the scene specially, the significance of taking selfies has gone beyond just having fun, producing a souvenir or showing off. When people are able to use a reversal camera on their smartphones it becomes as easy as looking into an extension of the body of a photographer. Though it does have a certain viewpoint: shooting from an angle of 45 degrees above the forehead is considered to be the most acceptable in general. A change in the handling a camera (reversal smartphone cameras and the usage of selfie sticks) results in a change of perception of the images. While the 45 degree angle offers a larger field of vision, it also places the photographed (photographer) in a place where closer interaction with their surroundings is possible, especially in public events. Although an identical viewpoint is a common feature of selfies, in a way, the selfie has altered the viewers’ used experiences of perceiving how the subject participates in the event through an image. Furthermore, the affect can be felt completely differently from the interactions. Affects, in Spinoza’s definition, are basically ways of connecting, to others and to other situations, and always involve a process of affecting and being affected. Brian Massumi expands on this with the idea of belonging. He mentions that affects are our angle of participation in processes larger than ourselves – a heightened sense of belonging, with other people and to other places.7

How easily can someone seem to be a part of a political movement via social media? When the convenient selfie-sharing process of Instagram combines with the function of being regarded as a disseminative tool of politics, to a large extent, it meets the people’s fantasy of politics. But the fantasy is inaccessible to the senses, it actually requires a multiplication of images. It seems that we have become accustomed to our being in the images whilst being affected in cyberspace, as well as by the importance of being seen in images. But if this is a false impression, the achievement of an illusion, the result could just as well be more indifference to politics. Interestingly, the response of the “Like,” has become a kind of manifestation of no standpoint and no reaction.

1. See www.digitaltrends.com.

2. See www.independent.co.uk.

3. Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964), p. 8.

4. Ibid.

5. See www.qz.com

6. See www.thedailybeast.com.

7. See Brian Massumi, “Keywords for Affect,” in The Power at the End of Economy, (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2014), pp. 103–112.

Hu Wei (1989, Dalian, China) is an artist doing a MFA program at Dutch Art Institute, Arnhem. He holds a BA Degree in Painting from Central Academy of Fine Art (2008 – 2012). Since 2013, he has been working as a programmer at an independent art space named Institute for Provocation. Currently he is based between Beijing and Amsterdam. Hu works with multi-media including video, installation and micro-performance. His work has been exhibited in Amsterdam, Berlin, Tijuana, Beijing, Shenzhen.