Next Year at Marienbad

Notes on 360-Degree Multi-Narrative Film

September 8, 2017essay,

In this contribution to the 2016–2017 session of Open! COOP Academy, Maya Watanabe looks at the devices on which fictional spaces depend: from architecture in theatre to the frame in film to the omnidirectional camera in virtual reality. In tracing this trajectory back to Alain Resnais’ 1961 film Last Year at Marienbad, Watanabe exposes the progressive dissolution of separation between body, location and language. She thereby shows how make-believe space is made believable, and perhaps, how it is becoming more real.

00:13:06,787 --> 00:13:15,496

Been here long? No, but I’ve been here before. Do you like the place? Not particularly. It just so happens that we always end up here.

Alain Resnais released L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad) in 1961. In the film, a man meets a woman during a social gathering at a mansion. Shot in three different palaces as if they were one place, the characters walk through the corridors in a labyrinthine remembrance of a previous encounter. It’s unclear if they actually met before or if it’s an oneiric recount of a false memory. Dialogues are repeated in different rooms, and the fragmented narrative seems to belong to a frozen time without a possible way out.

A and X – the names of the female and male protagonists – don’t have fixed identities. They have different skins and it’s difficult to determine if they are themselves, or if they have shifted to become other people.

An atmosphere of disorientation impregnates the movie. Last Year at Marienbad, with its altered spatial references and ambiguous characters, reshapes the visual and conceptual definition of place, space, language and subjectivity.

00:46:46,173 --> 00:46:54,081

Always walls, corridors, always doors, and on the other side, yet more walls.

What defines theatre – in the classical sense of the term – is a spatial convention. Circumscribed by architecture, its fictional space is a box: a building isolated from the outside world. Theatre’s structural arrangement separates the stage from the stalls. Seated in the stalls, spectators agree to believe in a represented drama as far as they share in the presence – time and space – of the actors. Coetaneousness and experience are key to enabling theatrical fiction.1 Left out of this calculation, non-representational areas – like backstage – are an extra-scenic void.

Unlike theatre, space in film is mainly afforded by the camera’s frame, not by architecture.2 Actions are delimited by the frame, and the remnants – the off-scenes – are what happen outside the field of the action. The narration of events is written through cuts and montage, and the point of view is not from our seats in the stalls but through the lens of the camera.

The foundation of spatial representation lies in the relation to the audience and what is being seen. Whether theatre or film, geometries are ‘necessarily anchored by the viewer’s cone of vision – a single point of identification that “frames, focuses, enunciates” and thereby, authors’.3 Everything beyond the cut-off to reality belongs to peripheral vision and reminds us of the difference between ‘here’ and ‘there’.

Virtual reality (VR) environments subvert questions about the viewer’s perspective and spatial geometry. When using VR headsets, immersive images – be they computer-generated 3D graphics or 360-degree films – cover all corners of the visual field. For the viewer, the impression of ‘being there’ exists in a threshold between fiction and reality, between live experience and mere observation. It’s in that intersection where a potential for a different status of the image appears.4

In immersive realities, by relying on a sense of presence, the cinematographic concept of mise-en-scène and the theatrical concept of stage meet. In the same way, both off-spaces are annulled: being off-camera and being off-stage. There’s no longer framing, a stage area or geometry – not even a visible interface.

00:25:28,695 --> 00:25:47,181

They have come to the top of a cliff. He stops her going too near the edge while she points to the sea stretching to the horizon. Then you asked me their names. I said their names didn’t matter.

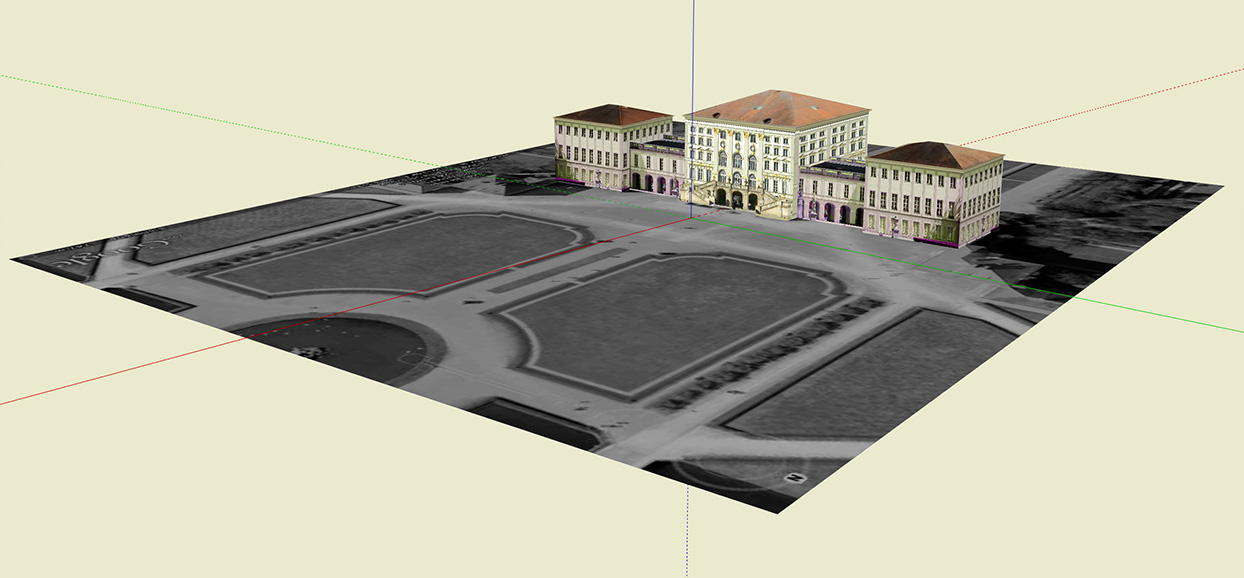

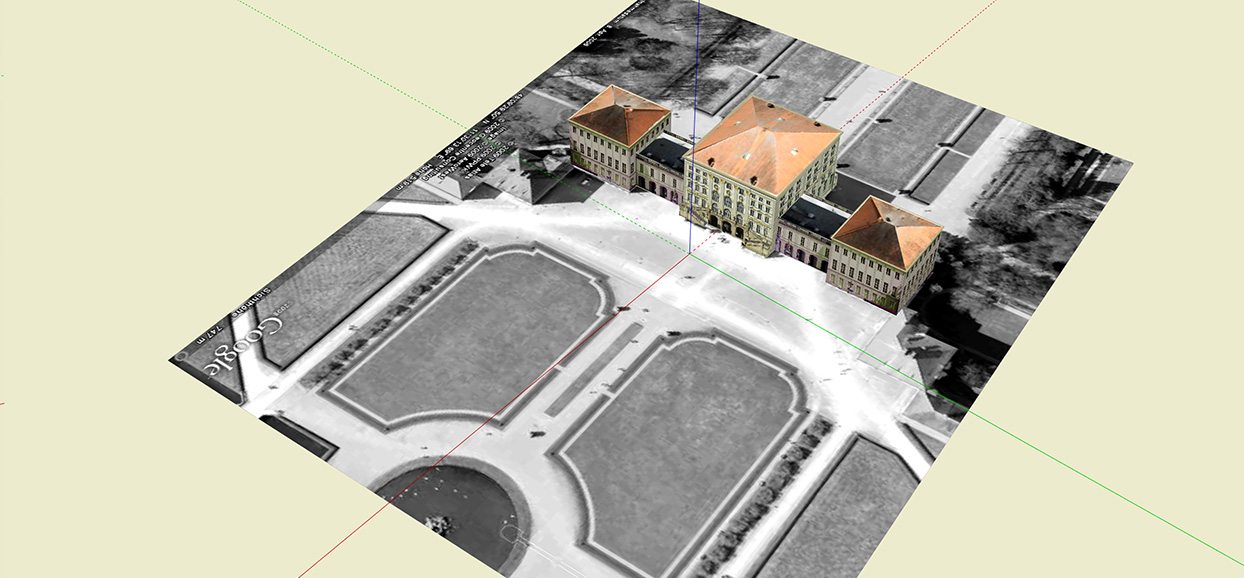

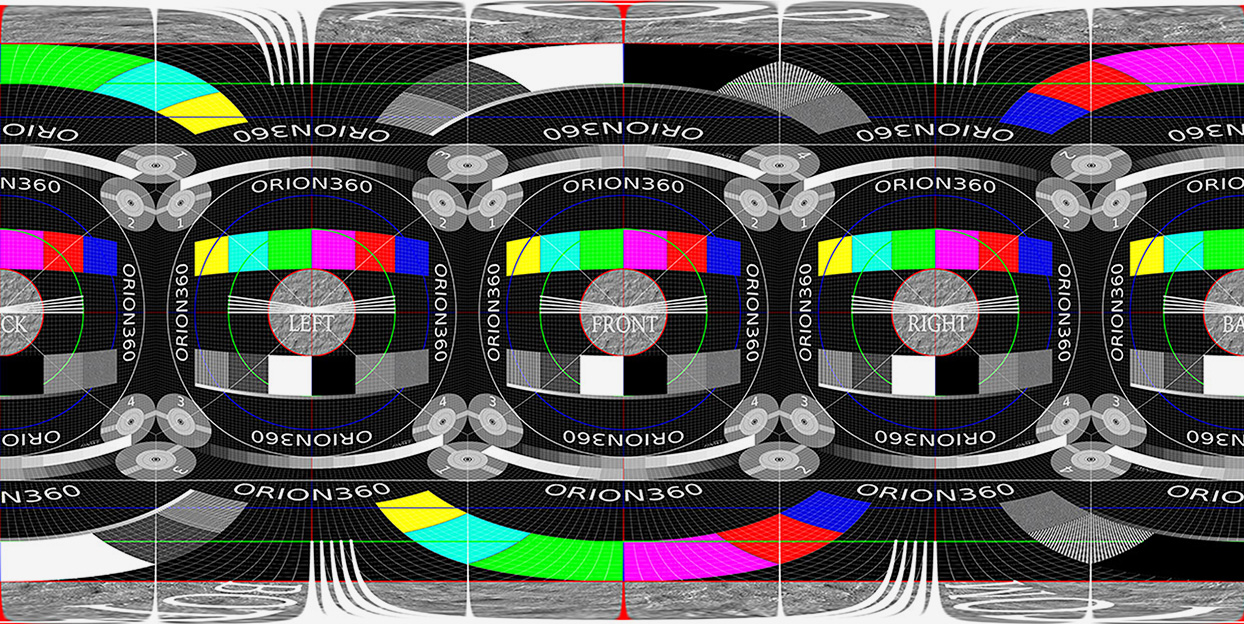

A 360-degree video is generally filmed with an omnidirectional camera that records every direction simultaneously. The footage is merged together into one spherical video that covers the whole visual field. From a film-shooting perspective, when an omnidirectional camera is placed in a room, there’s no place to hide: it records everything.

Shot and reverse shot techniques are no longer part of a 360-degree video’s language. With the disappearance of the frame’s outside, the filmic match cut principle is negated and thus, the building of the narrative shifts from cinematographic editing to choreographed actions.

In the passage from traditional to virtual reality film, shooting can no longer be directed while recorded. As such, the director – together with the lighting and crew members – would be visible to the camera and, thereby, visible to the viewer. Thus, a preconceived situation needs to be rehearsed in order for it to happen autonomously in front of the camera.5

360-degree film’s particular set-up, production and methodology, also calls for a redefinition of narrative, place and subjectivity.

To access a fully immersive experience, a headset is needed. The images are no longer watched but experienced and navigated. By making use of the freedom of movement and attention, the viewer attains the active role of a ‘user’. A user can see whatever she or he decides to see. A moving image that was previously a delimited unidirectional projection, now explodes in a multi-directional narrative as kaleidoscopic as the attention of the user. Several points of attention open the door to simultaneous parallel scripts, overlapping events or braiding stories.

When the movie starts, VR cinema’s attendees wear headsets and teletransport themselves somewhere else. The first-person perspective offered by VR repositions the place in relation to the body’s location and reformulates its representation in language. Deictics such us ‘I’ or ‘here’ are redefined since the ‘I’ is every participant watching the same movie, and the ‘here’ is not the cinema theatre but the film in which the ‘I’ is immersed.6 The interrelation among body, location and language is broken, and recalls a disembodied brain in a simulated world-model.7 Without an interface that allows us to enter and exit fiction, how does the brain read fiction in what it sees?

Last Year at Marienbad appears to be the precursor to conceptual questions raised by VR. The film’s undefined characters announce the displacement of the subject produced by immersive environments: an interchangeable disembodied self whose representation is based on a phenomenological relation to a spectral world. A world that, like in Last Year at Marienbad, confuses geographic place with mnemonic space. Under a VR experience, proprioception and emotions seem to be the only bodily reminders left before the connection between place, body-location and space shatters.

1. Roland Barthes is the first to call theatre a geometric art in ‘Diderot, Brecht, Eisenstein’, in Image-Music-Text (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977).

2. A reflection on camera geometry related to the use of technology in courts can be found in Judy Radul, ‘Thousand Eyes’, in Media Technology, Law and Aesthetics (Berlin: Sternberg, 2011).

3. Ibid., 123.

4. Oliver Grau does extensive historical research into immersive images from early panoramas to virtual reality in Virtual Art, from Illusion to Immersion (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003).

5. Rope (1984) directed by Alfred Hitchcock, Russkiy kovcheg (2002) directed by Alexander Sokurov and Victoria (2015) directed by Sebastian Schipper are examples of rehearsed one-shot movies.

6. See Ken Hillis, Digital Sensations: Space, Identity, and Embodiment in Virtual Reality (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

7. Thomas Metzinger, Being No One: Self Model Theory of Subjectivity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press , 2003).

Maya Watanabe is a Peruvian visual artist who works with video installations. Her work has been exhibited at: Palais de Tokyo, Paris; Matadero Madrid, Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco; Das Fridericianum, Kassel; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima; and Kyoto Art Center among others. She has been featured in festivals including: Videobrasil, São Paulo; LOOP, Barcelona; FILE, São Paulo; Madrid Abierto; Havana Film Festival; and Beijing Biennale. She has also collaborated as a set designer and audiovisual art director for theatre plays performed in Peru, Spain, Austria and Italy. Watanabe is based in Amsterdam.