Park Life

April 7, 2004essay,

The need to keep out the big, bad, unsafe world is growing, as evidenced by the increase in enclosed spaces. Using the concept of the ‘human park’ introduced by Peter Sloterdijk in 1999, as well as old and new examples from film, architecture, art and television, Sven Lütticken wonders whether the new societal form these places conjure up for us is in fact safer.

Contemporary space is quickly becoming less homogeneous. ‘Gated communities’ and other closed, fenced-in spaces are proliferating. This is not, of course, unprecedented. We are dealing with a return of something that modernity seemed to eradicate bit by bit, but this return occurs from within capitalist modernity (or postmodernity) itself. The modern age held out the promise of a continuous space that does away with old privileges and restrictions (based on class, religion, property or ethnicity). During the French Revolution, a proposal for a new map of France was drawn, with a structure of provinces that had the shape – at least in the first, most ‘ideal’ drawing – of perfect squares.1 The whole of France was turned into a perfect grid. This proposal, which was soon diluted until the grid structure was barely recognizable, shows modern, disenchanted, abstract space in a terrifyingly radical manner. In somewhat less spectacular ways, this development of modern space meant the erasure of the old legal and physical boundaries between the town and the countryside, as town walls were torn down and replaced by a less drastic transition. But the current segregationism, which appears to reverse that process, is in fact an effect of capitalist modernity itself. ‘Geometry and arithmetic take on the power of the scalpel. Private property implies a space that has been overcoded and gridded by surveying’ – and, elaborating on Deleuze and Guattari, if the scalpel cuts deep enough, the homogeneous, gridded space of modernity is cut into pieces.2 The modern nation state, although it may have seen internal spatial coherence and continuity as an ideal, is itself a fenced-in piece of land that people from other countries cannot enter at will.

Some of the new closed spaces, those intended for recreation or leisurely living, take the form of parks. Up to and well into the nineteenth century, access to parks was often restricted to a select elite; not everyone was deemed fit for a taste of Arcadia. But the nineteenth century also saw an increase in public parks, in theory open to all. Before the French Revolution, Marie Antoinette had a little Disney-like village constructed in the park of Versailles, the Hameau, where she could pretend to lead a bucolic life – away from the stifling court, but also free from confrontations with any real peasants or paupers. The age of the Hameau seems to have returned, not so much for individual queens as for a small bourgeois upper class. This tendency is reflected in symptomatic fictions like Peter Weir’s film The Truman Show (1998), whose protagonist is living in a small town that is in fact a huge, domed TV-studio – a simulation of life. The scenes that show this town, Seahaven, were filmed in a real Florida town, Seaside, a neo-Victorian fantasy for the wealthy. Seaside, built between 1984 and 1991, has also inspired Disney’s more recent Celebration development – a town completely controlled by the Walt Disney Corporation, where everything is banned that might be a blemish on this idealized ‘small town America’. Celebration, like Seaside, defines the good life in terms of a secession from the rest of society. The big bad world has to be kept at bay. A theme-park town such as this demonstrates that the real and fictional fenced-in spaces cannot be kept neatly apart; Celebration is a phantasmagorical reality. If The Truman Show is ‘just’ fiction, and non-Disneyfied gated communities ‘just’ a social and political reality, they nonetheless all function in the symbolic register of contemporary culture.

The rationale behind these settlements, with their varying degrees of fictionality, can be elucidated by the term human park, which was introduced by Peter Sloterdijk in his notorious lecture Rules for the Human Park (Regeln für den Menschenpark). At the end of this lecture, given in 1999, Sloterdijk made some references to genetic engineering that were ambiguous enough for many critics – Jürgen Habermas among them – to assume that he advocated some sort of eugenics in order to ‘improve’ the human race. Indeed, Sloterdijk seems to take it for granted that genetic engineering might really control such a complex affair as human behaviour; an assumption that might as well be criticized for its scientific naiveté as for its political implications. Sloterdijk’s remarks about genetic engineering were triggered by his despair over the state of the ‘humanist’ tradition. In his view the humanist Schriftkultur is threatened by the Dionysian mass media, which appeal to the beast in man. Whereas traditional Bildung, with its emphasis on text, has represented a humanizing, civilizing impulse, image-saturated mass media loosen inhibitions.

Imperial Now-Time

Sloterdijk perceives a similar conflict between word and image in ancient Rome, where the theatre (by which he means gladiators and similar brutal entertainments) triumphed over the culture of the classical orators, with well-known consequences. Taking ancient Rome as an example of what happens to a culture when it becomes decadent may be a familiar trope of conservatism, but Sloterdijk is original insofar as he sees the decline of ancient Rome in terms of a clash between media – the spectacular medium of gladiatorial fights versus the medium of writing. ‘As the book lost the fight against theatre in antiquity, so the school could now lose the fight against indirect forms of violence, in television, in the cinema and other disinhibiting media.’3 Sloterdijk might have paused to think whether he did not project a post-Gutenbergian view of the central role of ‘the book’ on ancient culture, and whether it is helpful in the present situation to complain about the decline of writing and accuse image culture as such of being dehumanising; it is however remarkable that the visual culture attacked by Sloterdijk actually seems to mirror itself in ancient Roman spectacles.

One of the biggest blockbuster films of recent times is Gladiator, in which the decadence of imperial Rome and its addiction to cruel spectacles are depicted in lavish detail, resulting in a violent spectacle that Sloterdijk would no doubt disapprove of. Whereas Walter Benjamin stated that the French Revolution saw itself as the Roman Republic returned, re-actualizing that era in a state of revolutionary now-time (Jetztzeit), today’s culture seems to have a privileged link with the Roman Empire rather than with the republic.4 Our now-time is an imperial now-time, not unlike that of the French Second Empire and of Victorian England: with a mixture of pride and fear of decadence and fall, these societies and their artists and architects mirrored themselves in (especially the late) Roman Empire. This passive and doom-laden now-time of empire cannot live up to Benjamin’s criterion that the momentary link forged in Jetztzeit between present and past is transformative, active and revolutionary. But for some, this now-time of empire can also give rise to a new revolutionary now-time, in which the early Christians, especially Paul, appear as contemporaries.5

Although his view on contemporary society is dominated by comparisons with Rome, Sloterdijk’s conception of society as a ‘human park’ has a pedigree leading back to Plato. But in his discussion of this ‘pastoral’ take on society, references to phenomena much closer to home seep in as well: ‘Since the Politikos and since the Politeia there have been writings which speak about human society as if was a zoo that is also a theme park; from that moment on the keeping of people in parks or cities seems like a zoo-political task.’6 Traditionally, parks are pieces of tamed, ‘refined’ nature, spots where nature has been made suitable for human consumption. Plants have been carefully grouped and groomed; if there are animals, these are either domesticated or – as in the Tierpark or zoo – put in cages. In theme parks, nature and its dangers are tamed by simulating them in all sorts of thrilling ‘rides’; a visit to a theme park is presented as an adventure, but as safe as a visit to the zoo to see lions and tigers. In the ‘human park’ theory of society, society is a kind of zoo for people, where their dangerous instincts have to be curbed. Sloterdijk sees people as ‘animals under the influence’ of culture; the guardians of the park have to be careful to make sure that these influences are beneficiary.7

It was the question how stability inside these parks can be maintained now the influence of the Dionysian mass media is growing that led Sloterdijk to his remarks on genetic engineering. The polemics over this aspect of his speech have tended to obscure the fact that Sloterdijk’s text, for all its phantasmagorical aspects – or indeed because of them – has the virtue of making a pervasive tendency in today’s culture explicit. Sloterdijk may refer to Plato, and his technocratic paternalism may also remind one of the modern state in its various guises (communist, fascist, democratic welfare state), but his text is above all marked by contemporary preoccupations. Sloterdijk is closer to Disney than to Plato, though Sloterdijk’s vision and Disney’s urbanism of exclusion can both be seen as the return of a past that was never really superseded. The new comes in the shape of a return of the ancient. With Celebration, the Walt Disney Corporation has created a residential theme park where the disintegrating tendencies of a society that is seen to succumb to Dionysian Enthemmungsmedien are locked out as much as possible. And Celebration is not unique: it is just one famous example of a new kind of urbanism in which towns are created as a refuge from a larger community, from society. If the big human parks that used to be called nations have become unmanageable, than smaller, safer human parks must be created for those who want to live a quiet life. However, reality has a way of kicking in, and Celebration has had its share of crime.

Jurassic Park

In the nineteenth century, a new conception of the park was born in the United States: the National Park, where a large area of nature is placed under protection. In this kind of park, it is no longer man who tames nature and hence protects himself from the wilderness; it is rather nature which is protected from human interference. The park is, however, in principle open to ‘the people’, as long as they follow certain rules. This kind of park has become ever more dominant; nature has to be left untainted and pure, and if there is none left it has to be created (like the areas of pseudo-authentic ‘new nature’ being created in Holland). In his writings from the late 1960s and early 1970s, Robert Smithson attacked the nature park ideology, then getting a new impetus from the counterculture. In his view, conservationists traded one myth (the myth of progress) for another (the myth of ‘untouched wilderness’). Smithson advocated a dialectical approach to parks, in which the human and the natural, the modern and the ancient co-exist and interact. Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of Central Park in New York, was the master of this ‘dialectical landscape’. Central Park is an artificial creation, a wasteland turned into a superior ‘new nature’ which kept evolving through the decades. Smithson described how in the early seventies the part of the park which is called The Ramble – with winding paths intended for thoughtful walks – teemed with ‘hoods, hobos, hustlers, homosexuals,’ whom he apparently regarded as the equivalents of wild animals: ‘Olmsted has brought a primordial condition into the heart of Manhattan.’8 Whereas communities like Celebration are be based on the premise that society as a whole (the big human park) has evolved into a scary place full of ‘hoods, hobos, hustlers, homosexuals’, Smithson delighted in a dialectical park that was far from ‘well kept’.

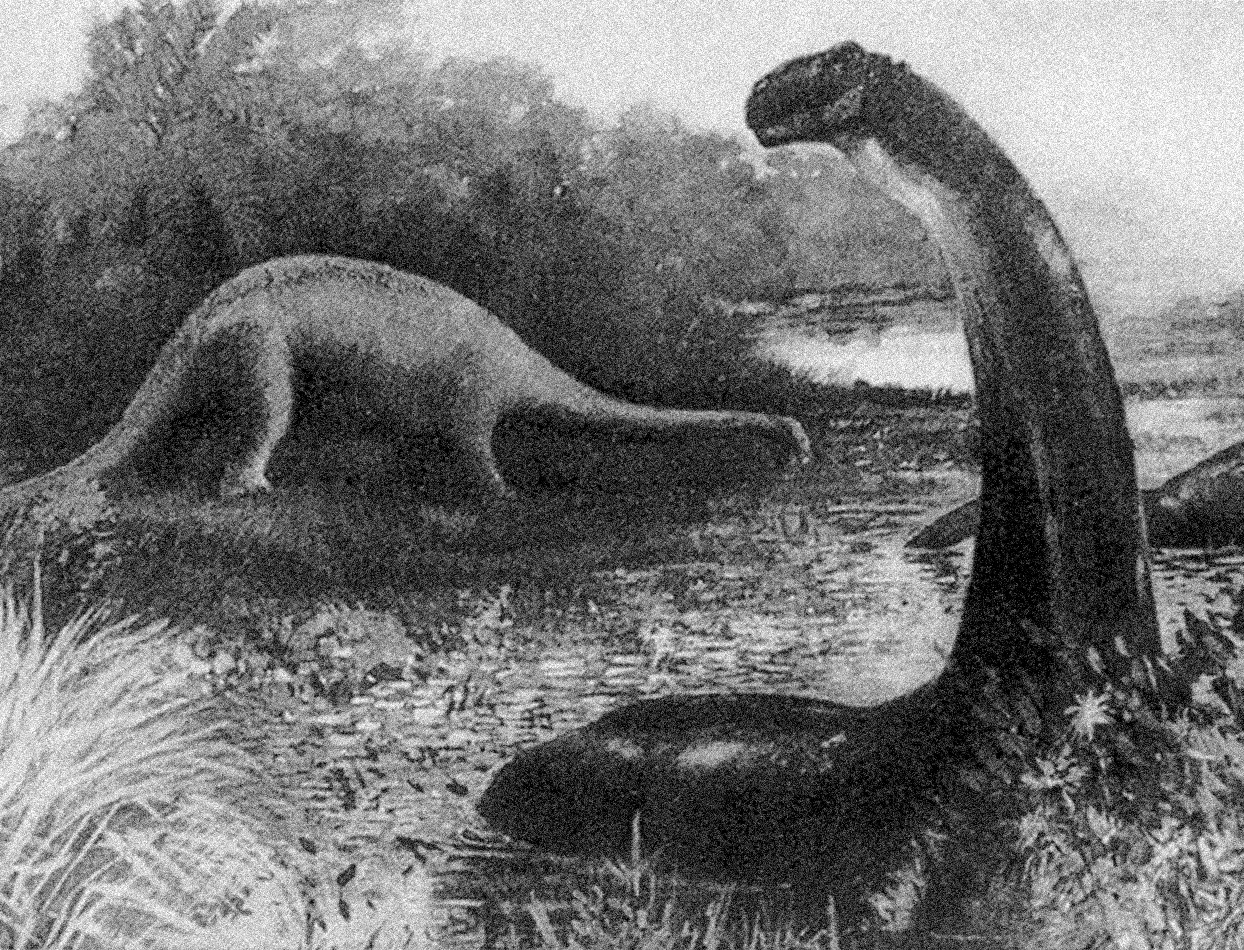

Smithson’s critique of the ideology of progress in postwar American culture went hand in hand with a fascination for the ‘primordial’, the prehistorical. The kitschy dinosaur paintings by Charles R. Knight were as compelling to him as anything in ‘official’ modern art (‘Note impressionistic treatment of water’).9 Smithson did not so much oppose the ancient to the contemporary as try to show how and when the present becomes posthistorical, postapocalypic. He wanted to identify points where the limits of the conventional view of historical progress are exceeded, so that a post-historical state is created that becomes one with its opposite, prehistory, which is also outside the bounds of conventional history. The industrial ‘monuments’ of Passaic, New Jersey, provided examples for this approach: ‘River Drive was in part bulldozed and in part intact. It was hard to tell the new highway from the old road; they were both confounded into a unitary chaos. Since it was Saturday, many machines were not working, and this caused them to resemble prehistoric creatures trapped in the mud, or, better, extinct machines – mechanical dinosaurs stripped of their skin.’10 In Smithson’s view, opposites always converge and no enclosure can ensure purity – whether it is ‘pure nature’ or an idealized reconstruction of small-town America.

The last decade has seen the rise of a widespread fascination for amalgams of high tech and nature, of cutting edge technology and the primeval. However, this development has been marked more by the dream of a perfect convergence than by Smithson’s insights into complex and messy co-existence. The Biosphere 2 complex, a system of linked greenhouses with a variety of climates, became a huge media hype when a group of scientists tries to live there autonomously in the early 1990s, without contact with the outside world. When it became apparent that there were difficulties and that the strict criteria (for instance with regard to ventilation) could not be met, the press turned against the project and its backer. Matters only calmed down when Columbia University took over the plant and promised to run it by strict scientific standards (recently, the university announced the end of the project). Whatever may be the scientific merits of Biosphere 2, it captured the media’s attention because it was (also) something more than science: it was a phantasmagorical New Eden, the promise of a healthy, balanced ecosystem. If it were possible to create a stabile ecosystem in greenhouses, in an enclosed, park-like space, then perhaps it does not matter so much if the real biosphere – the global nature park, which mankind has managed rather badly – goes to the dogs. New paradises could be created on other planets once this one is defunct. The ideal human park in the age of ecological awareness would have to be a nature park as well: Paradise Regained.

The ultimate – fictional – nature park of the last decade is Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) and its sequels. Smithson would probably have been mesmerized by this film, written by Michael Crichton: after all, the theme park entrepreneur in Jurassic Park uses advanced technology to re-create dinosaurs from their genetic material. Instead of creating peaceful inhabitants for the human park, as Sloterdijk hoped it would, the genetic revolution results in a new prehistoric age. This theme park is on an island, because the dinosaurs must under no circumstance leave their park (the inhabitants of, say, Celebration would not be amused if a T-Rex stalked through their town). Of course the island soon becomes a deadly trap for the people on it, as the dinosaurs start breeding and take over ‘their’ theme park. The park management has screwed up, and Spielberg can stage a virtual bloodbath which would probably have thrilled the Roman audience in Gladiator. Since dinosaurs first became the subject of science and of the popular imagination in the mid-nineteenth century, they have often been used to comment on human society; hence it is hard not to see Jurassic Park as a human park in disguise.11 After all, the dinosaurs’ voraciousness and greed is matched by the ruthless park director and his financial backers. They are true creatures of capitalism. And how could new nature created by humans be anything else but a human park?

A Franchised Free State

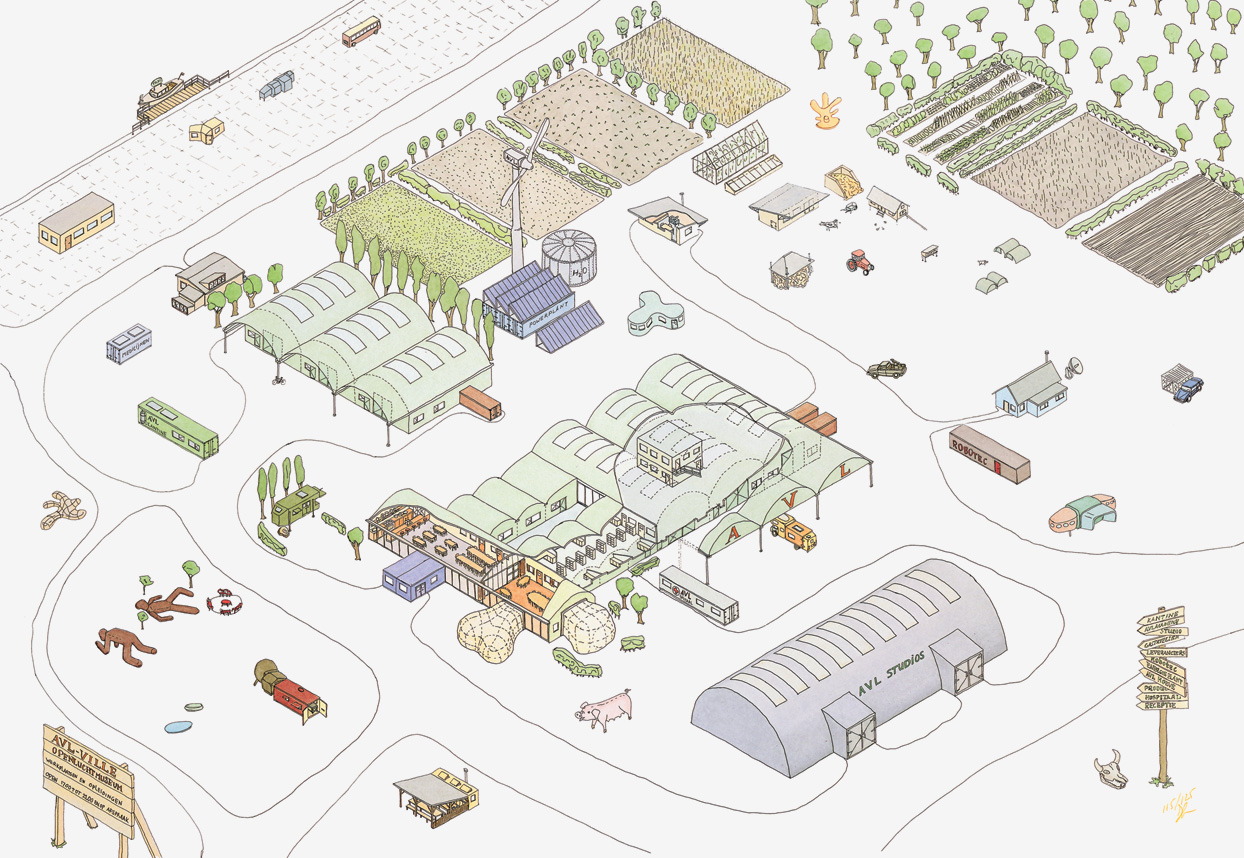

For a few months in 2001, the ‘free state’ of AVL-Ville existed in Rotterdam. AVL-Ville was founded by Atelier Van Lieshout, the art/design/architecture studio headed by Joep van Lieshout. The main part AVL-Ville was the studio compound in the Rotterdam harbour area, which was sealed off by a wall consisting mainly of containers. On the lot itself there were various structures scattered around in a rather haphazard fashion – including a field hospital and a car turned into a chicken coop. There was also a farm nearby, called AVL-Ville 2. After less than a year, AVL-Ville was closed because the town of Rotterdam insisted that the buildings and restaurant in AVL-Ville met its regulations (thus making explicit the fictional status of AVL-Ville as a state). Drawing from the bag of ‘radical’ theoretical concepts, one might opt to characterise AVL-Ville as a heterotopia, one of the divergent, marginal spaces that Foucault contrasted with the abstract, homogenizing space of capitalism – or as a TAZ, the Temporary Autonomous Zone posited by Hakim Bey.12 But for all the differences between these notions, both heterotopias and TAZs are in this abstract space, a part of it; they introduce difference, but they are not closed off. The fact that Van Lieshout envisaged a network of AVL-Ville ‘franchises’ throughout the world could be linked to Foucault’s conception of a network of heterotopias, but by staging a secession from society in the form of a ‘free’ state, Van Lieshout effectively copied the logic of gated communities and other human parks.

AVL works like the Atelier des armes et des bombes (a shed for making bombs) have led critics to comparisons with the reactionary American Militia movement as well as with the Unabomber: deluded attempts to stop the permanent revolution of global capitalism and to recreate some ‘normal’, stabile society. AVL-Ville has also been compared to David Koresh’s compound in Waco, Texas – another secession from society, and a particularly ill-fated one. At the opening ceremony AVL-Ville turned out to be much more festive and friendly. But as a small settlement that takes the form of a demarcated compound, AVL-Ville is, however closer to Waco than to, for instance, Constant’s New Babylon project from the 1950s and 1960s, which took the form of plans for immense structures that would have done away with the need to stay in a fixed place. Constant’s vision could not be further away from Sloterdijk’s view of society as a ‘human park’ which has to be kept in order, although Constant’s Roussauist view of human nature may be as problematical as Sloterdijk’s conservative one: Constant foresaw a nomadic homo ludens engaged in a perpetual dérive. Between New Babylon and AVL-Ville, something fundamental has changed: models for social reform (or revolution) are no longer aimed at society at large, but at small secessions from this society.

In the final analysis it is not Waco that comes to mind in the case of AVL-Ville, but Celebration, as incompatible as Van Lieshout’s libertarianism may be with Disney’s paternalist social vision – and as much as it may be inspired by commune experiments of the late Sixties and Seventies, which also followed the logic of secession. Both Celebration and AVL-Ville are small human parks that have split off from a society that is seen – although for different reasons – as a large human park that is run in an unsatisfactory manner. Both use the status of private property in the modern state to split a piece of land off from the state, to turn it into a micro-state. The concept of ‘franchises’ is also obviously derived from corporations such as Disney, who can effectively blackmail national governments, because they can always hop to the next countries. Multinationals are after all the true nomads; in the past decade it has become clear that perhaps only capital lives up to Deleuze and Guattari’s romantic theory of nomadism; only capital is always on the move, without any definitive ‘reterritorialization’ taking place. In Asia, this has led to the establishment of ‘free-trade zones’ where normal law is suspended: in these zones, corporations (or rather their contractors) can pretty much do what they want (which includes barely paying their workers).13 A discussion of AVL-Ville in this context may seem strange, as AVL-Ville was not about exploiting workers or evading taxes. It tried to use the human park approach to society against its aims, but it did not actually break with this approach. It was a human park dressed in the garb of a ‘pirate utopia’.

Even more than books, films or inhabited theme parks (whether by Disney or by Van Lieshout), it is the medium of television that has exploited the fact that we have come to think of society as a human zoo. One successful ‘reality TV’ format was a show where a group of carefully selected people live with each other on an uninhabited island, a Jurassic Park for humans. In the even more popular Big Brother, the human park was been reduced to tiny dimensions: one house with cameras everywhere. It is the ultimate secession, the private home, turned into a peepshow. Meanwhile, reality soaps about Ozzy Osbourne and others reduce boredom by focusing on bizarre and famous individuals, rather than on assorted nonentities. Having lost the faith in the manageability of society we watch how, in this microcosm, people just barely manage to get along; we watch how the secluded little human park turns out to be just as complex and unmanageable as the big human park that once used to be called society. As in Jurassic Park, the enclosed space turns out to be a trap rather than a way out.

This essay previously appeared in the New Left Review, no. 10, July / August 2001, p. 111–118 and has been specially revised for Open.

1. Daniel Nordman, Marie-Vic Ozouf-Marignier, Atlas de la Révolution Française 4: Le territoire (1): Réalités et représentations, Éditions de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris 1989, p. 29–30.

2. Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (1980), transl. by Brian Massumi, The Athlone Press, London 1988, p. 212.

3. ‘So wie in der Antike das Buch den kampf gegen die Theater verlor, so könnte heute die Schule den Kampf gegen die indirekten Bildungsgewalten, das Gewaltkino und andere Enthemmungsmedien verlieren, wenn nicht eine neue gewaltdämpfende Kultivierungstruktuur entsteht.’ Peter Sloterdijk, Regeln für den Menschenpark, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 46.

4. Walter Benjamin, Über den Begriff der Geschichte (1940), in: Rolf Tiedemann, Hermann Schweppenhäuser (eds.), Abhandlungen: Gesammelte Schriften, vol. I.2, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1991, p. 701.

5. See Alain Badiou, Saint Paul. La fondation de l’universalisme, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1997; Slavoj Žižek, The Fragile Absolute, or, Why Is the Christian Legacy Worth Fighting For?, Verso, London / New York 2000.

6. ‘Seit dem Politikos und seit der Politeia sind Reden in der Welt, die von der Menschengemeinschaft sprechen wie von einem zoologischen Park, der zugleich ein Themen-Park ist; die Menschenhaltung in Parks oder Städten erscheint von jetzt an als eine zoo-politische Aufgabe.’ Sloterdijk, op. cit. (note 3), p. 48.

7. ‘Zum Credo des Humanismus gehört die Überzeugung, dass Menschen “Tiere unter Einfluss” sind das dass es deswegen unerlässlich sei, ihnen die richtige Art von Beeinflussungen zukommen zu lassen.’ Ibid., p. 17.

8. Robert Smithson, ‘Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape’, in: Robert Smithson, The Collected Writings (ed. Jack Flam), University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London 1996, p. 169.

9. Robert Smithson, ‘A Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Art’ (1968), in: ibid., p. 85.

10. Robert Smithson, ‘A Tour of The Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey’ (1967), in: ibid., p. 71.

11. On the dinosaur in modern and contemporary culture, see W.J.T. Mitchell, The Last Dinosaur Book, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 1998.

12. Michel Foucault, ‘Of Other Spaces’ (1967), Diacritics 16, 1 (1986), p. 22–27; Hakim Bey, T.A.Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, Autonomedia, New York 1991, p. 95–134.

13. Naomi Klein, No Logo, Flamingo, London 2000, p. 195–229.

Sven Lütticken is a member of the editorial board of Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain. He teaches art history at VU University Amsterdam; is the author of several books, including History in Motion: Time in the Age of the Moving Image (2013); and writes regularly for journals and magazines including New Left Review, Afterall, Grey Room, Mute and e-flux journal. At the moment he is working on a collection of a essays under the working title 'Permanent Cultural Revolution,' and editing a reader on art and autonomy. See further: www.svenlutticken.org.