Peep Peeps = ⋆≋≬※⁑⊸

October 4, 2017artist contribution,

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen’s sound essay is part of the Open! COOP Academy research theme (Against) Neuralgia: Care of the Brain in Times of Cognitive Capitalism. Sound plays a crucial role in positioning oneself in the given surroundings. Memory is important in perceiving sound without knowing its source. ‘Peep Peeps = ⋆≋≬※⁑⊸’ offers a space for the reader to create, within her own imagination, using sounds – and at the same time, to question what is lost and gained in translation. Have you heard the sound of a rock singing? Or a conversation between fish and seaweed? Do you know what light and shadows sound like? Have you heard your own toe complain after a long day? How can we understand sounds whose sources are unknown, and reflect ourselves in these? What are we missing in what we see?

Imagine yourself floating on chronic ▤s∺✪n≣d waves, the soundscape of every subject surrounding you.

I picked it up from aside the river.

It is dark and shiny.

Has a⊶ bit of crack

It rests in my hand, soaked.

In s⋄⋇⋖⋰il⋼en⋊⊗⊱c⁂e, the rock starts to sing.

P ick pi ck

M u rmu r s n u u uuuuur ee

M ur mm ooorch cher r a l l eeer

tinkle lee l l n g l e

t week tik t wi n kle

ρeeeppli lla

I’m waving the sound, hearing rock sing. They are all fa↺∴mi∾≖⁗lia⁞r elements; however this seems un◮◎❉╳❢✴ real for human experience, unable to reach.

Common sayings like “seeing is believing” give our eyes the central role in our engagement with the world. But there is little doubt that listening plays a critical part in how we navigate and understand our environment.

—Lawrence English

When one receives information in the form of sound while being completely disconnected from re✸△a◐◠↝⋑⋈lit⋗∰⋄⊾∎y▪⋘, there is a process of int∅e⁁◘rp▯▮re◈↭⊹⊛⁗⁗⁗tation involved. Hearing sound without knowing its source, memories are triggered. Memory does not fade like a Polaroid photo – it keeps on being refreshed each time some precise elements provoke anamnesis through each and every cell in our brain and body.

But how far can we s⊹•e※e⁑✽ or imagine when listening to a soundscape? How far can we connect unfamiliar sounds to our m✺m❝ri✜⇎es? How far and how precisely can we extend our vision through our ears? How c≲⊗⊷l≬≋∹e∢∗∮∝a√‡r‽‿⁗ can we see a bird when we hear it singing: What kind of bird is singing? How big is it? Is it he or she? What is lost within this translation and conversion from sound to image and what is gained?

When one cannot connect, one also cannot understand the present reality. This is where memory tends to play an important role. Unknown sounds gradually evoke deep emotions to fill the void in our understanding of the present environment. A part of our brain that controls our senses is also responsible for storing emotional memories. Dysfunction in these areas can create difficulties and distance between sights, sounds and other stimuli that one should or should not be afraid of, resulting in fear and anxiety.

For example, the high pitch s⇴※u✦n⋒d…⋩ of a drill piercing through rocky hard concrete could make you experience fear, since it might remind you of your last dental appointment. W⋚⁂◧◤✡↯h≉i∔∎le the sound of a Champagne cork popping could remind you of an explosion caused by hot cooking oil in a pan.

A cracking sound and the smell of burning could bring you back to a joyful moment at summer camp or to barbequing with friends.

You might have experienced a thrilling sensation of fear, when a hairdresser slowly moved a shaver around your ears to trim the hair there. The sound and vibration might have softly reminded you of a tree being cut down by a chainsaw.

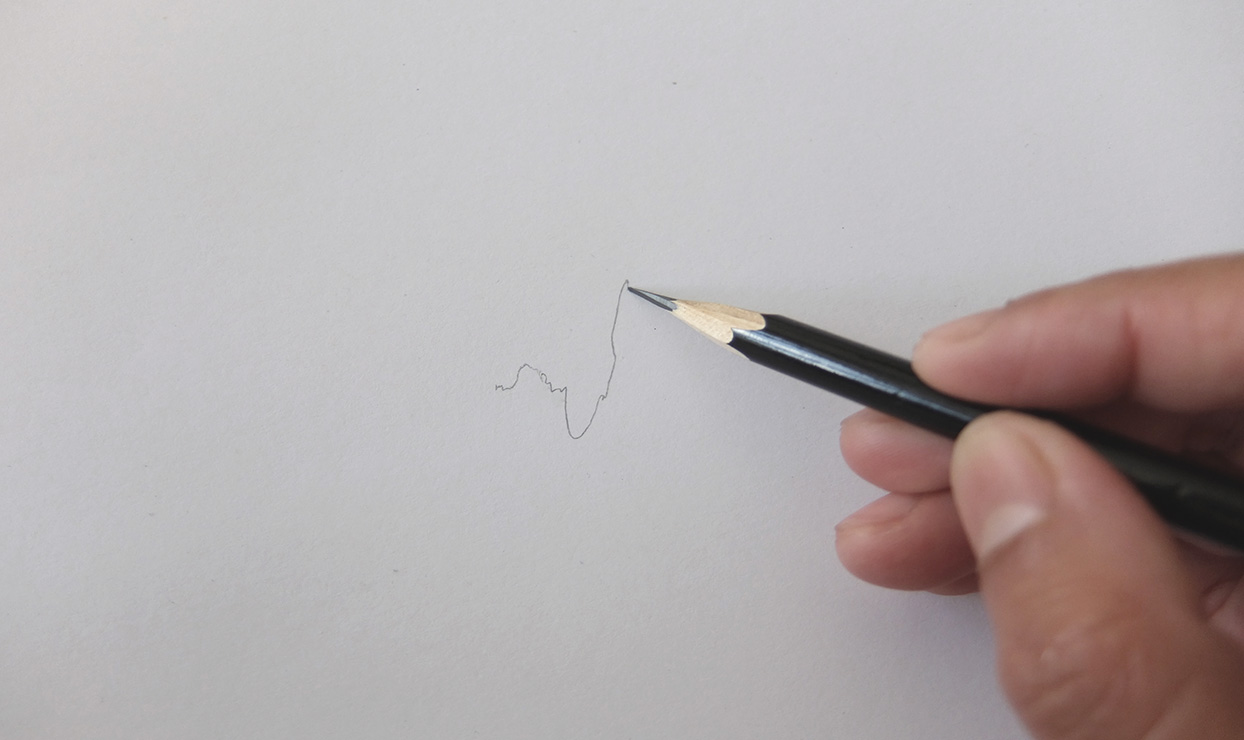

Very much like wordless writing, doodles or scribbles, drawing and creating images use hands as tools to t◆✹r↹a⇎⊙n∆sl∂‷at∅⁑╗e sound into drawing.1 The hand is a device used to sense and analyze an invisible, however existent, earthquake – in this case, sound waves. In this way, when one’s hand moves around to create a drawing, it works in the same way as the nail of a seismograph, which engraves the different waves and energies of the earth moving. It is a way to visualize invisible waves and there is no concrete meaning behind it. However, there are characters of communication beyond it offering m╢✲❍e❆a➤n✸i✳⇝✯•ng by way of aesthetic intuition, and not by verbal expression. There are some deep and rooted emotions we cannot express through words but somehow when it comes to drawing, we could let ourselves capture hidden waves, hidden regularity from something, which you really manage to express and translate from sound through drawing.2 The process of translation happens not only during writing or drawing from sound, but it also happens when one reads or interprets the message. What do we lose and what is gained during this process?

The translating process allows the destructive area of meaning to emerge where there is a void ‡‴※⁑▲◎✠⇴∝※◆▩╭✫✃✱ between original meaning and its interpretation. The subject is being approached from different angles. This phenomenon allows new meanings to arise in the cracks of linguistic context.

1. Based on the continuum from text to asemic writing to abstract images by Tim Gaze.

2. Based on Federico Federici’s artist talk on the occasion of the Asemic Exhibition curated by Michael Jacobson at Centro Cultural Casa Baltazar.

Pitchaya Ngamcharoen works with anything from ants to monkeys, from food to animal droppings. Her recent occupation and research deals with the hierarchy of human senses, which, she believes, establishes the hierarchy of knowledge that we apply today. How do we avoid isolating scent while de-hierarchicalizing / deconstructing the human senses and advocating for the senses of smell, taste and touch to exploit the politics of their value? She also adopts a word / phrase by Chheng Phon, a master of Khmer classical dance, as a practice: “A garden with only one type of flower, or flowers of only one color, is no good.” See further: pitchayang.wordpress.com.