Reflections on Artist Organisations International

June 9, 2015review,

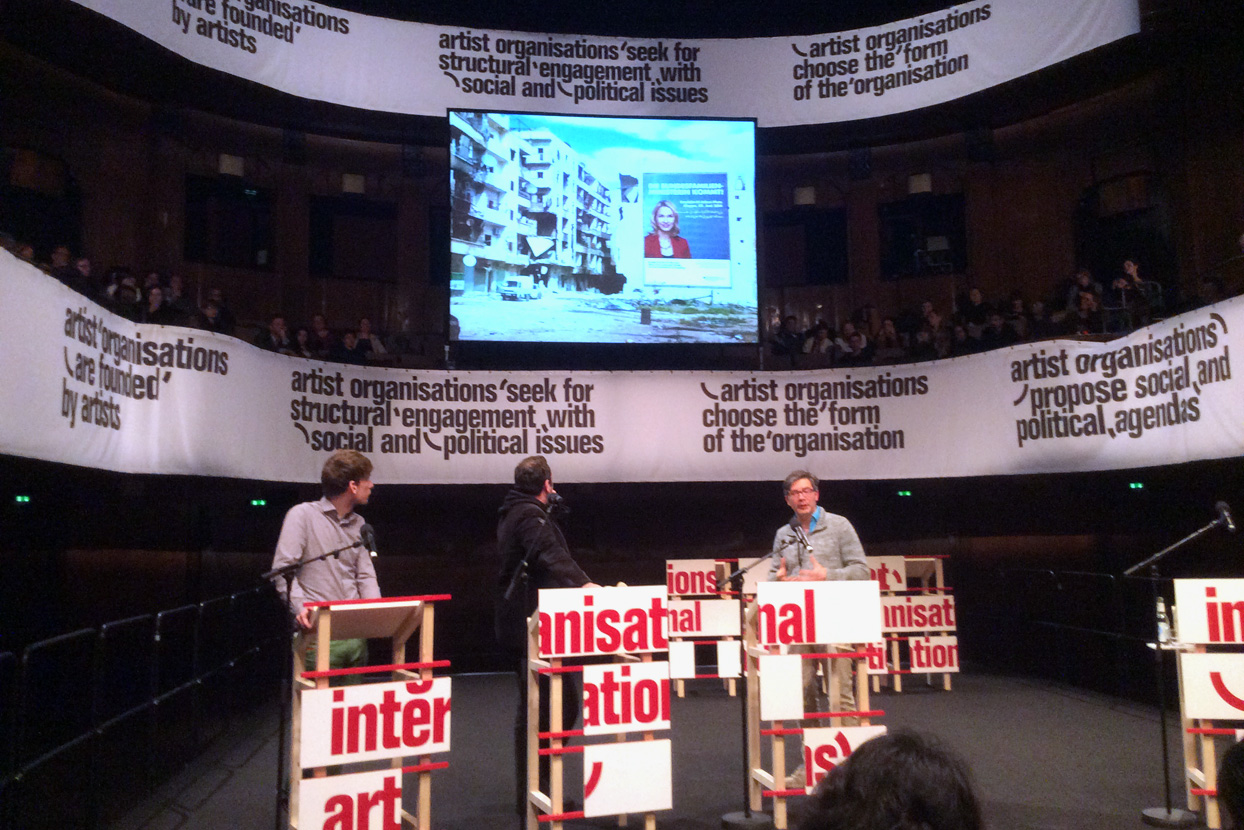

The Artist Organisations International conference, organised by Florian Malzacher, Jonas Staal and Joanna Warsza, took place in Berlin’s HAU theatre from 9 to 11 January 2015. The organisers emphasised how it seems that more and more activist artists are creating organisational structures that increase the effectiveness of their artistic actions and productions, which also makes it possible for them to exert an influence on the ethical standards of the contexts in which they work.

Jonas Staal’s New World Summit (NWS)1 is a prime example of this kind of organisation. It is dedicated to those whose words have been taken away by contemporary parliamentary democracies for example because they have been labelled as terrorist organisations. To be more precise: The NWS gives the floor to “blacklisted and stateless political organizations”. It was established a few years ago, and it’s more of a process than a project and is founded on the political principles of the participating artist. When artists set up foundations in this manner, it allows them to assume a position in the political hierarchies, which are near to where they practice their art.

Artist Organisations International also does research on the various forms these organisations can take, their socio-political agendas and the activist and artistic strategies they employ. It is comprised of some twenty organisations that gave presentations, including two institutions (Institute for Human Activities2, International Institute of Political Murder3), a laboratory (The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination4), a bureau (Büro für Antipropaganda5), an association (Artists Association of Azawaad), a movement (Immigrant Movement International6) and even a university (The Silent University7).

Our purpose in this essay is to investigate the debate regarding current activist and artistic practices8 by emphasising five different perspectives: the focus on organisations in the arts, the demand for art’s impact, the role of propaganda, the regional perspective and the types of activism

From objects to projects to organisations

The transition from an artistic practice based on projects to one based on processes serves as the conference’s connecting theme. Artists seeking an increased say about the context that determines who they receive their funding from as well as the context in which they become noticed, are increasingly presenting their practices in the form of organisations. At the heart of this trend lies an ideological motive: artists want to free themselves from the capital and investment logic of galleries and the international art trade, which forces artists to deliver tradable “products”, rather than meaningful interventions or processes that lead to change. At the same time, artists have a desire to free themselves from the funding systems in which newly available Dutch government funds – such as The Art of Impact fund9 – make increased demands of a bio-political nature (Negri and Hardt 2000). Bio-politics is currently utilising the social sciences to influence the processes of change via data regarding the population’s current condition, as well as “policy” based on this knowledge.

It seems that art and culture are at last being employed to serve bio-political (administrative) ends. The problem is, of course, what remains of art’s critical capacities, when art and culture are relegated to a supporting role as a policy strategy to deal with the funder’s guidelines (in this case the government). The art critics at BAVO called this kind of art “NGO art” which cannot, according to them, be anything but politically weak and artistically substandard art.10

In their search for new organisational structures, many artist initiatives are not only trying to avoid the capitalist system, but also trying to prevent their projects from being used as new forms of social work because an autonomous position is nearly impossible to sustain in this kind of situation. Maintaining one’s autonomy requires sharp political analyses that support the related artistic actions. Jonas Staal’s NWS is a good example of this, not only because the “terrorist” organisations have been thoroughly researched, but also because this research introduces new perspectives on political themes such as the nation-state. BAVO’s case for radical activism – a practice radical in both its political analysis and its artistic approach – only becomes possible as artists and their own organisations gain more control over the nature and the objectives of their projects.

What sort of impact?

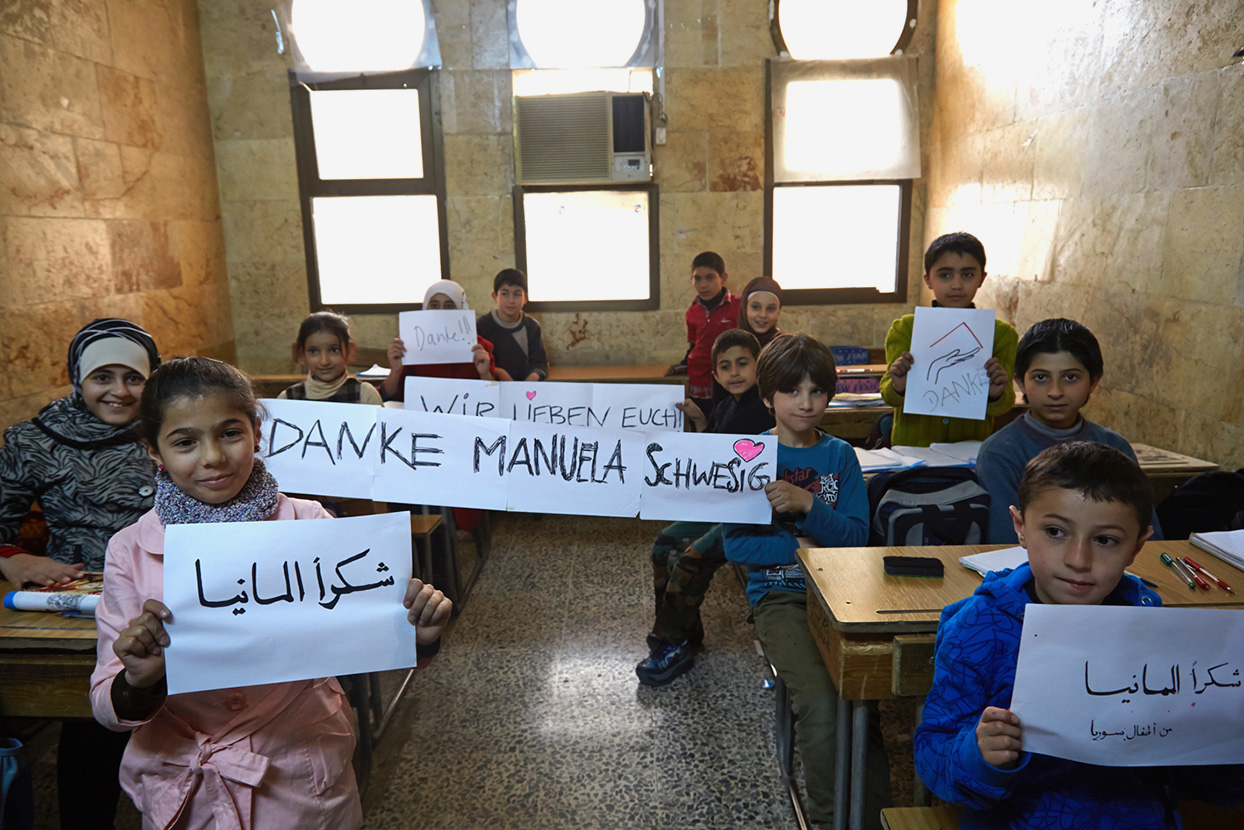

All of the artist initiatives presented at the conference have their own political and social agendas. Despite this common ground, it didn’t take long before a dilemma arose that cut through the debates like a knife: Should political or activist art have a practical social impact and literally interfere in everyday reality, or should it concern itself with a symbolic-critical practice that aims to expose deeper layers of awareness and understanding? This crucial question arose after the Zentrum für politische Schönheit (ZPS) made its presentation and thereafter became the dominant question. The ZPS’s presentation of its Kindertransport project, which refers to the 1938 transport of 9354 Jewish children from Germany to England, is an appeal to the German people to offer asylum to an equal number of Syrian refugee children. The project combines visual interventions that refer to the Second World War and political actions that offer concrete results in the form of asylum for many Syrian children. These activities are combined with images that offer commentary that can be construed as ironic: for example, an image of happy Syrian children who thank the German Minister of Family Affairs Manuela Schwesig.11

The fierce reactions this project received during the conference probably have something to do with how the “innocent” victims of the Holocaust are made to play a part in the partly effective, partly ironic web the ZPS has woven around the German citizens. The combination of collective German guilt, optimistic actions and ironic visual language may be largely responsible for the furious reactions of some of the public against the ZPS. There was a feeling that the ZPS was playing with or trivialising the victims’ actual suffering.

Meanwhile, the initiatives of WochenKlausur12 and The Silent University made new socio-political practices possible and they are heading right toward the goals they’ve set for themselves. Although they do not use playful visual language or irony, they do make effective use of visual images and social strategies. For instance, WochenKlausur placed a brightly coloured cabin on a terrain where various parties engaged in sincere discussions about the housing of addicts. In their presentation WochenKlausur’s representatives indicated that they were only interested in solving the problem and not in leaving their artistic mark. They prefer to transfer their effective artistic strategies via a shared toolbox so that others can use them.

While Claire Bishop’s appeal to socio-political artists is to make artistic quality the decisive factor along with the creation of art (Bishop 2012)13, this was not WochenKlausur’s priority. They preferred to focus on the peremptory reality while artistic intervention merely served a supportive role. While in the past someone like Thomas Hirschhorn have preferred to discuss his artistic choices, Wochenklausur has chosen the opposite strategy by viewing artistic choices only in light of their social and political consequences. Meanwhile, the Silent University cannot be accused of being involved in political symbolism as they attempt to train asylum seekers in Europe, which is a realistic platform that offers a voice to those who are not considered citizens within the asylum system. This allows them to share their knowledge with others.

The symbolic power of critical art was ironically emphasised by the absence of the Cuban artist Tania Bruguera from the Immigrant Movement International. Bruguera’s project, which was presented via a video screen during the conference, showed a situation in which a microphone was placed in a public space somewhere in Havana. This act was enough for the police to arrest and jail Bruguera. Simply by performing her symbolic act in a public, and therefore political, space Bruguera had committed a political act, which was interpreted by the police as an actual intervention. After all, people could actually take their place behind the microphone and this is how political acts become symbolic acts.

While symbolic artistic acts “only” encourage people to think, there is also the utilisation of art that goes far beyond the usual parameters so that art simply becomes an alibi. For example, the Artist Association of Azawad used their presence at this 'art' conference to ask for money for the educational projects which are part of the separatist movement in northern Mali. In 2012, during Jonas Staal’s first NWS in Berlin, this organisation was still considered by Mali an illegal “terrorist” organisation. The NWS’s art context gave Moussa Aq Assarid on behalf of the National Liberation Movement of Azawad ample opportunity to present their political ideas and, during the AOI, they used the opportunity to ask the organisation to host their next meeting in Azawad. This would not only provide legitimacy to their new, as yet unacknowledged state, but also the means to realise their social and educational objectives. Taking part in this kind of conference is not solely driven by artistic arguments, but by a concrete political agenda: the acknowledgement of The National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad’s struggle. Their art is only evident in the design of their flag and banderols (speech scrolls) for their new nation, and the establishment of political propaganda meetings that include song, theatre and dance.

Their political agenda became even more interesting in light of Dutch artist Renzo Martens’ presentation. Martens called into question the way our Western art system is embedded in a global revenue model, in which the capital market, museums and galleries are usually the winners. Martens’ Enjoy Poverty projects involve his working with Unilever employees in DR Congo. He founded the Institute For Human Activities in DR Congo to allow these employees to gain a share of the artwork’s revenues. The institution has ensured the exhibiting of their chocolate statues of Congolese people in European museums. These statues are made of soft clay in DR Congo and are then exported to the Netherlands via 3D scans, where the images were printed on a 3D printer using DR Congo chocolate. The revenues from these statues go directly to the Congolese participants and further valorises their artistic input in Western museums.

Although the Congolese participants Martens employs benefit from these projects, it is the western museums who, according to Martens’ own vicious analysis, benefit the most. So, he not only managed to parody the good intentions of the critic-activist artist, including himself, but he also managed to reveal the multi-layered and difficult to ignore the dependent relationship within the global financial circuit, which, on the one hand, finances art projects and, on the other, maintains a firm grip over them. Martens asked who ultimately benefits from these good intentions? After all, good intentions are immediately co-opted by the economic political system of which activist artists are an irreplaceable part.

Counter-Propaganda Strategies

Artists not only live in a propaganda-driven society in which images in public spaces seek to win over their audiences in a one-dimensional, populist way, but they also live in a mediated society where the media’s logic has to be obeyed in order to gain visibility and presence. How can artists resist or counter the dominant media logic? Perhaps by making use of existing images and structures and taking them “over the top”, like the Institut für politische Schönheit attempted to do with their “Kinderproject für Syrien” project. Because, wherever propaganda tries to avoid debate and focus on programming the public with its commercial strategies of temptation and persuasion, political art will seek to initiate a debate.

Propaganda involves attempting to make viewers believe in the reality of fiction. Political art, meanwhile, seeks to question the fiction of reality and avoid the creation of consumptive or passive viewers, and instead stimulate an active, critical public. Artists and designers have for decades experimented with strategies to employ the media in subversive ways. Some of the strategies currently being used include over-identification (playing the game to such an extent that you are actually ridiculing it), hacking (breaking into a system as an uninvited guest) and alienation (representing the known in a way so that it’s both recognised and not recognised).

We also saw some very interesting examples at the conference of two less prominent strategies: first we have re-enactment, an alienating, theatrical repetition of an event from the past that allows you to relate to the original event in a new way. This strategy was used by Yael Bartana’s Jewish Renaissance Movement In Poland (JRMiP) and in the Institute of Political Murder’s re-enactment of old tribunals. In both cases people are seen working with fictional and theatrical elements in a staging that positions itself as being real, with the aim of questioning reality as a fictional, constructed reality. The JRMiP effectively represents how propagandistic elements within the arts can be used to question the inevitable mingling of fact and fiction (Žižek 2006). The JRMiP is a fictional movement; its members are played by actors and it has a fictional leader and a fictional logo. Fictional events are re-enacted in order to realise a fictional goal: the return of the Jews to Poland. However, what’s happening within this movement is not only based on historical fact, but might actually be real or may become reality. This kind of movement can be formed fairly easily and can be used to encourage Polish Jews to return to Poland, their country of origin.

In certain respects, the JRWiP reminds one of the NWS. In both cases, there is a “what if” question, and the opportunity that art offers is used to make something possible within the arts, which in reality does not (yet) exist. In both cases, the public is addressed as if that which is happening is real. At the NWS, however, “real” representatives replace alleged terrorist organisations, while in the JRWiP everything is a performance. This is why in the case of JRMiP, we can speak of fictional re-enactments, while the NWS uses the space that art offers to give a desired reality a chance.

A number of organisations at the conference presented anti-propagandistic strategies, which are related to critical investigative journalism. The Institute for Forensic Architecture14, for example, conducts research into the methods used by Europe’s intelligence agencies to create a more impregnable Fortress Europe. This research was presented to potential refugees in a visual manner so that they could prepare themselves for what awaits them. Investigative journalism that serves as a direct intervention for the parties concerned can have great impact, but because of its advocacy nature, it also disqualifies itself as “independent” journalism. The second example of critical journalism as art is The Office for Anti-propaganda’s15 Refugees Library16. The Office for Anti-propaganda is also conducting journalistic research that will hopefully immediately benefit refugees. It has produced notebooks of refugees’ stories and tips by asylum seekers who have already received their refugee status in Europe.

Artistic strategies in a regional perspective

In addition to a great number of artist initiatives from Europe, the conference also presented initiatives from other parts of the world such as the Kurdish movement from Syrian-Kurdistan, the self-proclaimed Tuareg state of Azawad in northern Mali, Cuba, the Philippines, Kiev, Israel and Argentina. The groups, platforms, organisations, institutions and movements with their very diverse ideas concerning artistic strategies (for change), were especially diverse regarding the notion of using ironic layering in their projects. While the European initiatives almost all favour using theatrical re-enactments or games that blur fact and fiction and play with journalistic or political discourses and traditional roles of social workers, union activists, marketing and branding specialists, the Cuban, Philippine, Iraqi, Kurdish and Malian contributions are characterised by a collective seriousness, which is due to the violent context in which these artist groups operate. They are engaged in organising dissent in societies marked by real (physical) repression, while in Europe, people are mostly confronted with the seductive and propagandistic, visual imagery of a consumer society that attempts to make us ignore the buried violence of (impending) unemployment and legal insecurity, and attempts to simplify the political as nothing more than a management issue. While European artist initiatives attempt to justify their right to exist through a strategic or ironic identification with all kinds of roles in traditional civil society, organisations such as Gulf Labo17, Immigrant Movement International, Artist Association of Azawad, Artists and Educators of Rojava, and Concerned Artists of the Philippines do not hesitate to make a very direct connection between art and politics. They do this either by organising direct political interferences during public debates or by addressing the political debate directly. Curiously enough and unlike the other non-European groups, the Israeli and Argentine groups used powerful ironic strategies.

While European artist initiatives are threatened by the cooptation strategies of various governments that attempt to subject the arts to policy goals through subsidies, the groups from the other regions are busy addressing what we think is a very important underlying debate concerning the political sphere. Some of these groups, such as the Artists and Educators of Rojava, have taken this to quite an extreme and claim that the political always requires an artistic response.

Meanwhile, the Concerned Artists of the Philippines and the Artist Association of Azawad presented the most obvious as an extension of a liberation movement or opposition party, with projects involving political cartoons, posters, plaques and theatrical productions that are traditionally referred to as “demonstrations” or “occupations”, and are also considered to be propaganda. The reactions to the Syrian-Kurdish Artists and Educators of Rojava’s contribution added a new dimension to the debate about propaganda. Because of the ongoing civil war, the group’s members were, of course, unable to attend the conference. But they were represented by a documentary which, according to one of the reporters, looked more like a traditional war propaganda movie. It showed images of Kobani, which despite the presence of IS, remains a free enclave thanks to the efforts of a group of Kurdish men and women who are especially inspired by traditional storytelling, songs and political meetings that emphasise the importance of an egalitarian organisation. Art forms forbidden by IS such as music and political images, are used as tools in a political struggle while politics is more or less “unmasked” as an art form.

Rojava’s goal of creating a new state or new stateless societies requires visionary skills that, they believe, can only arise from a liberated artistic imagination. The Artists of Rojova have taken this debate about the politics of the future quite far by focussing on statelessness and citizenship. They are trying not only to inspire stateless citizens in their war-torn areas, whom they deliberately do not refer to as refugees, but are also attempting to educate them about the feasibility of something “beyond the nation state” in which men and women are considered equal. They advocate a “post” or international statelessness that attempts to raise the consciousness of citizens about the importance of daily life’s performances, such as opening a bakery every morning despite the violence, and of the importance of participation of (unveiled, armed) women in the political battle. In the context of these ongoing civil wars, this kind of everyday life performance gains both political and artistic overtones as creations that have shed their self-evident normalcy and, in decimated regions, they almost literally become a “creatio ex nihilo”, a creation built out of nothing.

Is the nature of these kinds of projects, in which faith in the positioning, connective and creative power of art is foremost, a regional phenomenon? Can one say that Europe is not really seriously looking at itself and is producing images that are a commentary on, or a game consisting of various images (as a reaction to a deluge of more than one hundred years of propagandistic images)? Meanwhile, in other regions, where people are fighting for their lives, images are created based on a belief in the visionary, creative power of art, which have no need for ironic, critical layering? The criticism that the Artist Association of Azawad had of Argentina’s International Errorist Movement made this very clear. After Enrico Zukerfeld presented the International Errorist Movement’s latest consciousness-raising project that focuses on Monsanto’s polluting activities, a representative from the Artist Association of Aswad wondered: “Are animals and plants more important than human beings?” This effectively shows the different priorities of the artist initiatives emerging from various war-torn areas.

From criticism to activism

The organisations at the conference, demonstrated a broad range of art practices from critical deconstructivist or ironic strategies to more positive, constructive attitudes. The participating groups increasingly want not only to highlight abuse, hidden agendas and false presumptions, but also offer solutions and alternatives via the creation of platforms, new structures and alternatives that address the art and gallery worlds, consumer society, the unequal distribution of civil rights in fortress Europe and alternatives to the nation-state.

We see a debate developing between those who treasure the symbolic-critical function of the arts and those whose main ambition is to introduce processes of change based on a perhaps naive and romantic longing for visionary art which, in a crumbling world, believes in art’s reality-shaping powers. But whether it concerns the influx of refugees created by capitalism and neoliberalism’s growing gap between the rich and the poor, or how horrifically our climate is being destroyed, or dysfunctional parliamentary democracies, or oppressive school structures or post-colonial nation-states at war, the participating artist organisations all feel a need to employ their artistic potential to create alternatives and to use the autonomous space created by the arts to produce something concrete in society without transforming the arts into a kind of safety net for dysfunctional governments. There is clearly a “regional” difference between Western European artist groups who resist being used for the political ends of neoliberal democracies that projects the image of the West as the best of all possible worlds and those artist collectives from other parts of the world who sometimes simply want to use art as political propaganda or demonstrate that political debate and politics in general need the creative skills of the visionary artist.

Conclusion

The conference organisers addressed the urgency of discussing the nature of propaganda at this time. Propaganda, as an inevitable and tempting mix of fact and fiction, is employed by both consumer society and neoliberal governments, as well as by activist artist collectives to respond to the question: What world (or reality) do we prefer to live in? This conference’s message was that the world is in a terrible state and art and artists can no longer stand along the sidelines, engaging in art for art’s sake, and that it is essential for artists to join forces, share strategies, obtain funding and increase their influence based on artists’ own objectives, outside of the institutionalised art world.

And although Jacques Rancière noted that both the heteronomous (critical) and the autonomous poles of art are continually questioning each other, in fact, the contributors to this conference showed how these poles are inextricably interrelated and that the one cannot survive without the other. The artist organizations we discussed above may differ in their approach regarding organisational formats, regional perspectives, the choice of activist, propagandist strategies; they all insisted on the artistic value of their work.

References

- Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells. London: Verso Books, 2012.

- Negri, Antonio and Michael Hardt. Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Rancière, Jacques. Het esthetische denken. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2007.

- Žižek, Slavoj and Sophie Fiennes. The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema. Mischief Films and Amoeba Film, 2006.

3. www.international-institute.de.

5. www.office-antipropaganda.com.

7. www.thesilentuniversity.org.

8. In this we are not following the themes of the organisation, but the themes which came to light at the conference right through the set themes.

9. “The art of impact” is a fund, set up by Minister Jet Bussemaker, which encourages artists, designers, mediators, institutions and clients to submit proposals that explore, reinforce and make visible the relationship between art and society. The objective of this open appeal is to stimulate new art projects that will have a clear impact on social themes and issues, especially themes such as: “liveable borough and city”, “energy and climate”, “care and wellbeing” and “(the circular) economy”. It is also described on the website: theartofimpact.nl.

10. www.bavo.biz.

12. www.wochenklausur.at.

13. A key element in the discussion about the instrumentalisation of socially engaged “participation” art is Claire Bishop’s book Artificial Hells (1990), in which she is the first to offer both a historical overview and a point of departure for the evaluation of this art form.

14. www.forensic-architecture.org.

15. www.office-antipropaganda.com.

16. Online archive: refugeeslibrary.wordpress.com.

17. www.gulflabor.org.

Anke Coumans is professor of the research group Image in Context at the Hanze University of Applied Sciences in Groningen. This research group is part of the Research Centre Art & Society. The different ways in which artists can bring about change in society is the key subject of study in this centre. Research is taking place on the following topics: the political role of the artist in society, photography as research, interculturality and the designer as agent of change in social contexts. Anke Coumans was educated as a film theoretician in Nijmegen and Paris and obtained her PhD in semiotics and the public image. In addition to her work for Hanze University Anke Coumans works at HKU in Utrecht. Together with Ingrid Schufelers she works as a social ecological designer on the project Membranen. In this project students, teachers and partners work together in a dynamic environment in which the redefining of social relations creates a playground which makes room for new perspectives, insights and possibilities for real innovation.

Bibi Straatman is lecturer cultural studies en (design) research methodologies at the ArtEZ Fashion Masters Arnhem and at the Utrecht School of the Arts, and postdoc Researcher for the Reserch Group ‘Image in Context’, Minerva, Groningen, about the (‘political’) role of practice driven artistic research & design projects in the public domain. Her PhD, Palimpsest. Slow thinking, on actorship and revolution, is about re-founding our notions of science and scientific research, by deconstructing oppositional pairs such as science & art, theory & practice, discursive, hermeneutic analysis & experience, mind & body. Main thesis: science, art and design are means to produce and support change and to acquire actorship. Science, art and design are tools for transformation and / or for transformational thinking.