Urban Politics Now

Re-Imagining Democracy in the Neoliberal City

January 1, 2007review,

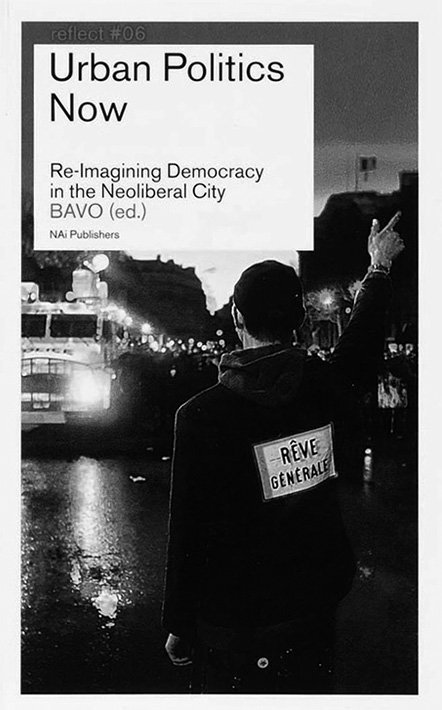

bavo (eds.), Urban Politics Now. Re-Imagining Democracy in the Neoliberal City, NAi Publishers Rotterdam, 2007, isbn 9789056626167, 224 pages

There has been a lot of moaning about the contemporary city in recent years. Pessimism dominates virtually every book published about the urban condition. The public space of the city is dead; it is controlled by neoliberal market economics and it is being inexorably privatized. Urban development is only rarely guided by social, political or societal considerations anymore; instead it is the product of market and consumer logic: the cold laws of supply and demand. Now that today’s cities are ever more seldom treated as a social and societal project but as a mere economic given, there is scarcely any such thing as ‘urban politics’ anymore. In critical thinking, pessimism even gives way to cynicism. Any critique of the current condition or ‘the system’ is deemed pointless and impossible, as it fated to be absorbed and co-opted by that very system. Urban Politics Now is a stinging indictment of this fatalistic and apolitical attitude towards the contemporary urban condition. The book is more than just another anthology of texts about the contemporary city, in which the various teething troubles of the contemporary urban condition are conveniently dissected and writers wallow in the by now all too familiar discourse and rhetoric of loss; instead it is a collection of essays that are all marked by an engagement that is sometimes infectious.

The BAVO editors make clear from the introduction that this book does not simply offer critical reflections on the inexorable depoliticization of the city, but seeks to formulate concrete alternative strategies for new forms of urban politics and democratic action. To this end they have brought together a heterogeneous selection of authors, with backgrounds in geography, urban planning, political philosophy and psychoanalysis. This last discipline, in fact, provides the book’s conceptual foundation. The current approach to the city, bavo asserts, is one of suppression or repression. In the neoliberal concept and management of the city, everything has to flow neatly and streamlined, and above all be profitable. There is no room for excess, marginality, unrest, or ‘dissensus’, or phenomena such as poverty, exclusion, illegality or crime. Problematic areas do not fit in the picture of a clean, attractive and culturally dynamic city. They are decisively cleaned up, redesigned and made attractive. Yet of course this radical suppression of characteristics and features inherent to any contemporary city does not resolve any problems. They eventually resurface – as psychoanalysis has taught us about psychological ailments – at a different time and in a different place, and often in a much more severe, sometimes even more violent form.

This idea forms the starting point of Slavoj Žižek’s comparison of the riots in the peripheral housing estates of Paris in 2005 with the catastrophic events that followed Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. In both instances, a segment of the population that for years had been ignored, even been made invisible, erupted into the forefront with uncontrolled violence. Neil Smith goes a step further and analyses the ‘revanchist’ strategies that lie at the basis of the invisibility of certain minorities in the city. Drawing on the example of Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s zero-tolerance policy on the homeless in the streets of New York, Smith shows that vulnerable minorities are increasingly hounded out of the city, or simply deleted from the cityscape. They do not fit in the image of the city that is essential for new investment and development. The homeless problem is far from solved, but at least it generates the necessary pretence of having done so. Guy Baeten pursues this analysis in relation to deprived neighbourhoods, which he aptly dubs ‘Neoliberalism’s Other’. By claiming that impoverished areas are the visible legacy of decades of social-democratic urban politics, neoliberalism exacts its sweet revenge. After all, one of neoliberal philosophy’s most powerful mantras is that poverty is your own fault and responsibility, just like that other slogan, that if you want a job, you’ll find a job.

Neglected neighbourhoods, from this standpoint, are a cherished target for lucrative and often unscrupulous processes of urban regeneration in which the genuine problem – pervasive poverty – is suppressed. The most vulnerable segment of the population is again hit first, as affordable housing is replaced by more expensive, often prohibitively costly dwellings for the wealthy middle class or other economic elites. In their respective essays about the city branding of Amsterdam and about the Comme des Garçons fashion brand’s ‘Guerrilla Stores’, Merijn Oudampsen, on the one hand, and Friedrich von Borries and Matthias Böttger, on the other, pose critical questions about the role and responsibility of the designer. The ‘creative class’ is not simply one of the favoured new groups of residents within urban regeneration projects; all too often they become part, under the guise of creative regeneration, of highly problematic processes and enterprises, of what bavo calls ‘machinations with a human face’. Cultural activists of all sorts are increasingly recruited to mediate in the redevelopment of a neighbourhood. Artistically motivated interventions serve as the lubricant for large-scale conversion plans, or as compensation for the inevitable struggles, unrest and dissatisfaction among local residents.

But just what are the alternative strategies presented by bavo and the authors they have mobilized? For this most of the authors, and bavo in particular, seek counsel from the French philosopher Jacques Rancière. Thinking about urban politics should focus its attention, bavo argues, on that group of urban residents Rancière calls la part des sans-part, or that segment of the urban population contemporary city policies do not take into account. An important part of the city’s population is responsible for the wealth and welfare of a society, but is not acknowledged as a valid part of that society, let alone accorded a voice. For example, it is no secret that in big cities, a significant but often invisible portion of the economic workforce – dishwashers, cleaners, pizza deliverers, child minders, and so forth – lives and works in illegal and often precarious conditions. It is this group of ‘second-class citizens’ that Rancière sees as the heart and the driving force of democratic politics and whose recognition he advocates. Following his example, bavo argues that it is the task of planners, architects, designers and urban sociologists – that group of professionals they feel ‘ought to be passionately committed to the fate of the contemporary city and its many victims’ – to offer radical countersolutions to the omnipresent processes of exclusion and negation in urban policy. The alternative for the post-political and antidemocratic approach of urban decision-making processes, according to bavo, consists in no longer masking the democratic struggles that inevitably go along with them, but instead making them visible, visualizing them. The essential repoliticization of the city requires a dramatization of urban inequalities and injustices. This is not followed, however, by concrete ideas for a translation into urbanistic and architectural design strategies, and they are not directly provided in the subsequent texts either. It remains essentially abstract advice. While in this regard the book does not fully live up to its own ambitions, it nevertheless makes for highly inspiring reading. In terms of the ambition to instil a political consciousness and conscience in the contemporary designers of the city and its spaces, the book succeeds brilliantly. And to be honest, the latter cannot happen too often.

Wouter Davidts is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Architecture and Urban Planning of Ghent University. He is the author of Bouwen voor de kunst? Museumarchitectuur van Centre Pompidou tot Tate Modern (2006) and in 2007 he curated the show Beginners & Begetters at Extra City, Center for Contemporary Art, Antwerp.