Wild Images

The Rise of Amateur Images in the Public Domain

April 13, 2005essay,

There is nothing new in camera images shot by amateurs being able to play a role as evidence and as a visual resource in the reporting and interpretation of significant events – witness the Zapruder film of the assassination of J.F. Kennedy or the Rodney King video tape. Now, however, digital media and the Internet seem to make an increasing intrusion of amateur images in the professional media inevitable. What is the status of these ‘wild’ images in the public domain? Do they reveal the new blind spots of the official news media? Or do they primarily demonstrate a public desire for images that almost eradicate the distance from events?

Photos of the torture of Abu Ghraib prisoners in Iraq were first made public in America in April 2004 via CBS’s 60 Minutes and The New Yorker, and then spread quick as lightning around the globe via the Internet and other news media.1 Less than five months later, a selection of the images was featured in the ‘Inconvenient Evidence’ exhibition at the International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York and the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.2 The digital photos were printed directly from the Internet and pinned ‘raw’ to the walls. ‘Inconvenient Evidence’ was organized by the critic, writer and curator Brian Wallis, the ICP’s Director of Exhibitions. Wallis’s intention was not simply to feed the prickly public debate about the events in Iraq, but also to generate a discussion about the new relationship between photography, digital media and conflict. After all, what was especially shocking about the Abu Ghraib photos was that they were not journalistic photos but amateur snapshots, personally made by the American soldiers as part of the torture, as a souvenir of the war, to mail to family and friends.

The exhibition obviously sparked protest. On an Internet discussion forum about the representation of violence, ‘Under fire’, in which many Americans participated, there was a heated argument about the ethics of the exhibition. The opponents of ‘Inconvenient Evidence’ did not think it legitimate or responsible to show photos of this nature in an art centre; the proponents praised Wallis’s courage and defended the necessity of exposing such material as widely as possible, wherever that might be.3 In the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad it was summarily argued that the photos in ‘Inconvenient Evidence’ would function as ‘quasi-artistic images, or as images that are interesting to look at in their own right’.4

The question is whether or not this actually says something about a pre-programmed, blinkered art public. The American critic Michael Kimmelman wrote that the exhibition had quite the opposite effect, and that the photos also had to be seen in the light of the continuing and suspect invisibility of official American photojournalistic images of the war.5 Kimmelman underscored the status of the images as personal, amateur snapshots that were never intended for public consumption, but for circulation within a small circle of family and friends. While public photos of suffering usually appeal to the viewer’s sympathy for the victim, and seem to be made by the photographer in our name, the Abu Ghraib photos confront us with the problematic and painful issue of what the photographers actually assumed about the viewers of their images. In any case, those images are evidence of a society suffering from amnesia, according to Kimmelman.

In this light, ‘Inconvenient Evidence’ was in the first place the statement of a political standpoint in the thoroughly frustrated American intellectual debate about the Iraq war, an attempt to give undiminished visibility in the public domain to what the Bush administration would have preferred to suppress as swiftly as possible – or to what American society itself suppresses. On this last point, the philosopher Slavoj Žižek wrote that the Iraqi prisoners were effectively being initiated into American culture, and were given a taste of the obscenity that lies hidden behind the values of human dignity, democracy and freedom held high in public.6

Secondly, the exhibition forced questions about the cultural and political implications of democratized digital production and distribution media (cameras, mobile phones, the Internet) for journalistic reporting and public opinion. ‘The pictures taken by American soldiers in Abu Ghraib ... reflect a shift in the use made of pictures – less objects to be saved than messages to be disseminated, circulated,’ as Susan Sontag formulated it in the essay ‘Regarding the Torture of Others’, written shortly before her death. ‘A digital camera is a common possession among soldiers. Where once photographing war was the province of photojournalists, now the soldiers themselves are all photographers – recording their war, their fun, their observations of what they find picturesque, their atrocities – and swapping images among themselves and e-mailing them around the globe.’7 And even though the government does not want to be confronted with them, there will be many thousands more snapshots and videos to come, argues Sontag. There’s no longer any way of stopping them.

The fact that the photos that escaped the Bush administration’s censorship of images of the Iraq war are amateur photos is what is significant here, and, as Sontag observed, this was less of an ‘unfortunate’ incident than the Bush government would have us believe. For a while now, there have been amateur photos of the caskets of American war dead circulating on the Internet, a genre of image that the American government decreed could no longer be made public.8 The civil rights activist Russ Kick successfully filed a request to the Pentagon under the Freedom of Information Act to gain access to many similar photos, but this time from the official Pentagon archive. He posted these on his website, ‘The Memory Hole’, which is wholly devoted to ‘rescuing knowledge’ and ‘freeing information’, and also indicates where the amateur photos can be found.9

Photos of coffins cost amateur photographer Tami Silicio her job – she worked for a transport company in Kuwait that is responsible for the transportation of human remains. And it is not improbable that the American military will be formally forbidden to take photographs or videos when ‘on duty’. However, it is ultimately difficult to impose such a ban on images, or the restrictions that ‘embedded journalists’ and photojournalists are subject to, on ‘the amateur’ in general: that could, indeed, be anyone, and they could be anywhere and everywhere, at all times. And with the Internet they certainly have a publication and distribution medium available to them with an unprecedented public dimension.

What Can You See?

Besides the official images, more and more ‘wild’ images will start to circulate in the public domain – these are ‘wild’ in the sense of being unedited and uncontrolled as well as savage and barbaric – made by chance passers-by, tourists, victims or participants, which manifest what the professional news media cannot or may not show. This does not merely have a revelatory, democratizing or ‘liberating’ effect, as with the amateur images of the Iraq war, but also a more perverse or obscene side. The wild images originate in part from a society that increasingly behaves like a permanent public, equipped with a camera as standard, and wanting to consume events from absolutely anywhere in the world while they are still unfolding, from the inside. And this is by necessity via imagery, since the public itself cannot be physically present everywhere.

With traditional public spectacles such as football matches that is not so unusual, but when it concerns accidents, disasters, wars or other dramas this narrowing of the distance between event and public is more problematic, and also more questionable. The professional reporting of the media, which are kept at arm’s length or cannot be on the spot immediately, is then supplanted by the snapshot of somebody who was there by chance and happened to have a camera at hand. That is what happened with the stabbing and shooting of Theo van Gogh: there was someone in the vicinity who immediately snapped a photo. By the time the press arrived at the scene the police had already created an impenetrable buffer zone around the corpse. However, there was already a picture, a fresh and authentic image, made before it was ascertained whether Van Gogh had died. Without this specifically pertaining to this individual citizen, could or should the photographer not have established this first? If in public space we start to behave more and more as a public that does not actively intervene but records events via the camera, like instant bounty hunters for images, then something like ‘fellow citizenship’ irrevocably goes out the window to do that. At the same time, the long-term significance of the transaction of events in the public sphere is subjected to pressure from the short-term interest of ‘premature’ images, which are not only capable of demanding all the attention but also steer the dynamics of the ensuing course of events and resolution.

The popular Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf published the photo of Van Gogh on its front page: newspapers and television will increasingly resort to material by amateurs in order to satisfy the desire for the first pictures. A few days after Van Gogh’s murder, during the police siege of a house in the Laakkwartier neighbourhood in The Hague, for which the entire neighbourhood was hermetically sealed, the frustrated television newsrooms resorted to the live report of an ‘eye witness’ via telephone, in this case a woman who coincidentally had a limited view of what was happening on the street from her living room. She was continuously pressured by the news presenter to relate what she was seeing. What can you see now? Can you see anything? Usually she could see nothing, though she tried desperately. This course of events, in which the interpretation of a serious event was delegated to a layperson, irrefutably contributed to the dispersal of fear in the media. Between event and report/image there was, literally and figuratively, absolutely no room for serious news analysis, interpretation, and signification or placing it in perspective.

Fake

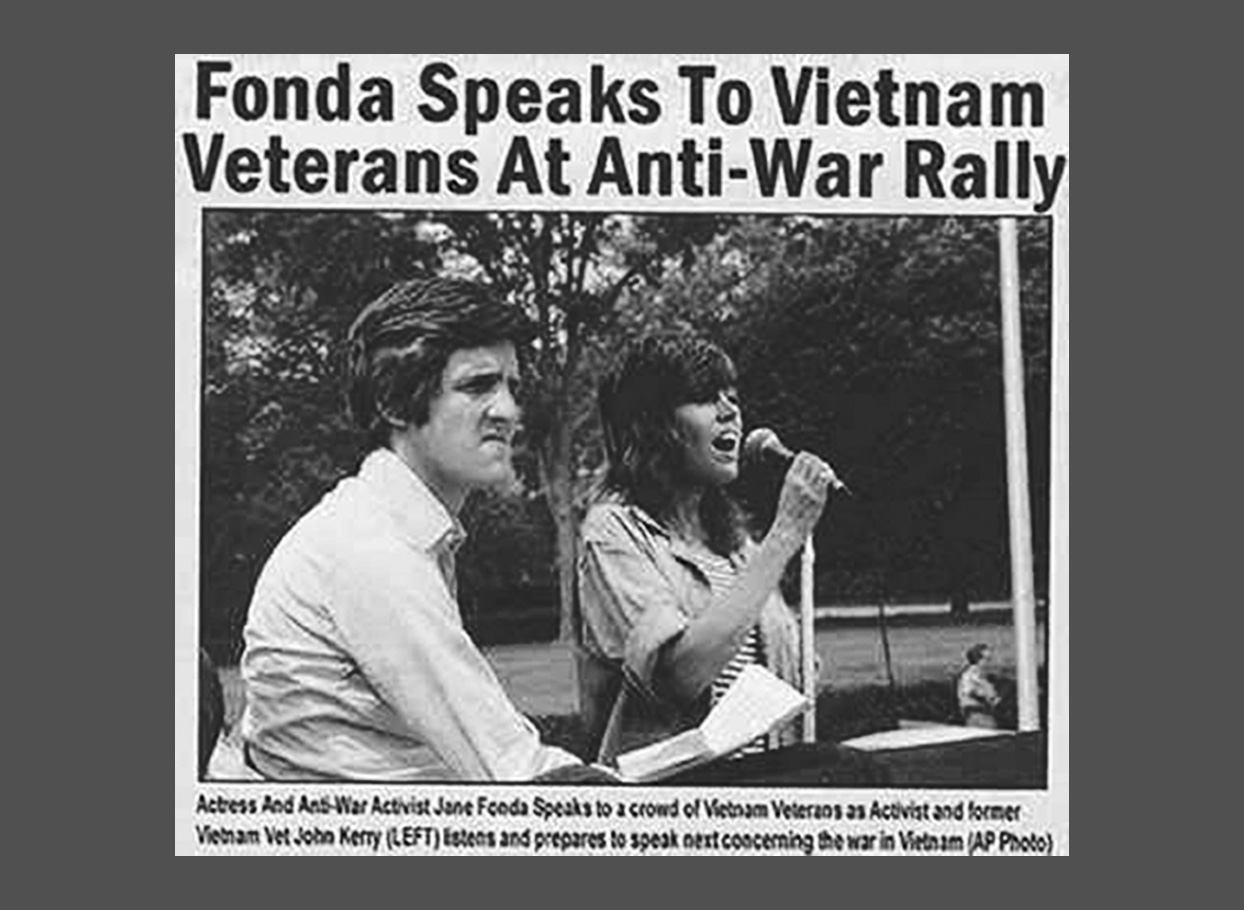

Until recently it was primarily lovers of pornography who distributed and traded their dilettantish ‘adult’ videos and rancid little JPEG files via the Internet. These shady, semi-public snuff media, in which it is often unclear what is real and what is manipulated, have now found their public counterparts in sometimes equally obscure, quasi-political images that want to masquerade as real. For example, at the time of the last American presidential election, there was a photo posted on the Internet which was then also published in the regular media. It apparently showed the Democratic presidential candidate, John Kerry, at an anti-Vietnam campaign in 1972 together with the ‘actress / activist’ Jane Fonda. Having caused a great deal of furore, the photo turned out to be fake, Photoshopped together by a still-anonymous ‘Internet activist’ and then appropriated by the Republican camp.10 And inspired by the ‘execution videos’ of Western hostages in Iraq, which were also recorded by amateur filmmakers, Benjamin Vanderford, a young American, single-handedly filmed his own staged beheading at home, which he then put on the Internet with all the resulting media confusion. His aim was to demonstrate how easy it is to ‘fake’ such a video and how easily the media can be taken for a ride.11

Fake images or ‘hoaxes’ of this kind being deployed as so-called evidence seems to be symptomatic for the fading evidential value of images in general. The authenticity of documentary images is indeed cast into doubt with increasing frequency, and in many cases not without reason. The question here is no longer whether the image is real or original in a material sense – hardly a meaningful question in the digital age – but whether the claim of the image to represent a social, political or historical reality is bogus or not. Did the depicted scene really take place? Image manipulation has, of course, been around since the invention of photography,12 but nowadays people often immediately question the veracity of what is depicted. This global suspicion stems only partially from the realization that the digital image-processing software no longer needs an external reality in order to produce a realistic image. Distrust of the image also springs from the growing realization that the ‘reality’ of the media is a genre.

Under the current dictate of visibility, people demand images of events, the right to be able to see and to show everything. But by the same token, through the agency of the democratized media, people now know from personal experience that the reality retreats behind the images, behind the ‘reality’. (Not for nothing is there the endless spin-off of many a reality TV programme, showing interviews with participants, who tell how it really was.) And since everyday reality and ‘normal people’ have become the media’s reality material, they are the ones who know what is kept off-camera and what is manipulated. Amateurs are not only increasingly professional producers of reality, but are also increasingly professional performers and an increasingly professional public. In a certain sense the media has thus created a ‘monster’, a monster that brings about an ironic inversion, with all the attendant crossing of boundaries: while the institutionalized media focus more and more on the private, often imitating an ‘amateur’ style, the amateurs and their media now have the public in their sights.

Re-enactment

‘To live is to be photographed, to have a record of one’s life, and therefore to go on with one’s life oblivious, or claiming to be oblivious, to the camera’s nonstop attentions. But to live is also to pose,’ Susan Sontag observed in her reaction to the Agu Ghraib photos. ‘To act is to share in the community of actions recorded as images. The expression of satisfaction at the acts of torture being inflicted on helpless, trussed, naked victims is only part of the story. There is the deep satisfaction of being photographed, to which one is now more inclined to respond not with a stiff, direct gaze (as in former times) but with glee. The events are in part designed to be photographed. The grin is a grin for the camera. There would be something missing if, after stacking the naked men, you couldn’t take a picture of them.’13

Slavoj Žižek’s perception of one of the Agu Ghraib photos seems to render this condition even more complex: ‘When I first saw the notorious photograph of a prisoner wearing a black hood, electric wires attached to his limbs as he stood on a box in a ridiculous theatrical pose, my reaction was that this must be a piece of performance art.’14 The term ‘re-enactment’ that is currently bandied around so widely, both in popular culture and in art circles, thus gains a more complex stratification. ‘Re-enactment’ refers to the large-scale, live reconstructions of historic events performed by hobbyists, often military battles or feats of arms.15 Within art, the term is primarily used in relation to the re-creation of historic performances by modern artists.16 In re-enactment, images, representations and documentary remnants are in effect repeated, whether motivated by a conservative nostalgic desire or as an attempt to gain a handle on history and the present. At the same time, new representations of historic representations are being produced.

In societies where in principle everything and everyone can become an image at any instant, and where everything and everyone is also constantly prepared for this, the logic of the re-enactment also works the other way around: the reality and its actors take their cue from the images, imitate the images, consciously or unconsciously. It is often said that the attacks of 9 / 11 were in the style of American action movies. And with the attack on Van Gogh you might assume that the perpetrator reckoned that his victim, along with the message that was theatrically pinned to his body with a knife, would be broadcast. In the fantasy of the perpetrator the image already existed, before it became reality. And if the events are not staged according to a pre-existing model or image, fictitious or real, then they become so in public perception. The pyramids in which the naked prisoners in Abu Ghraib in Iraq were stacked were similar to shows by cheerleaders in the us in which they also form pyramids, said the lawyer of one of the military personnel accused of torture. ‘Don’t cheerleaders all over America form pyramids six to eight times a year? Is that torture?’17

The dynamic of modern public space is largely based on the desire for visibility or transparency as a precondition for openness, order and communication. The wild images that are increasingly infiltrating this space lay bare the extent to which the paradigm of visibility is an illusion: they are subversive and liberating in their undermining of the official or professional images and their commissioners, as far as they have the performative wherewithal to break open and make visible suppressed or hidden realities. At the same time they are therefore also the fulfilment of the visibility ideology in optima forma, and they exaggerate the obscene or perverse of the permanent boundary-breaking that is inherent to this. The wild images contribute to the culture of spectacle, but simultaneously blow it up by manifesting themselves outside any given order. Wild images are barbaric images, and therein lies their power and their peril.

In the meantime, a new battle of images will start to become apparent, a battle that is not only about the authenticity of the images, but also about their legitimacy and exploitation – and even more so than previously. Did what the image shows really and truly happen? Can what the image shows really be seen by others? And by whom exactly? And who has the right to control the images, or see them? A certain tragedy for reality lies hidden here, insofar as the evidential or disturbing function of the image will increasingly refer back to the image itself, and less and less to the reality from which it has been extracted.

1. See Seymour M. Hersh, ‘Torture at Abu Ghraib’, The New Yorker, 10 May 2004. www.newyorker.com. See also Seymour M. Hersh, Chain of Command. The Road from 9 / 11 to Abu Ghraib, HarperCollins, New York 2004.

2. ‘Inconvenient Evidence, Iraqi Prison Photographs from Abu Ghraib’, 17 September – 28 November 2004, icp, New York City / Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, 3 October 2004 – 2 January 2005. www.icp.org.

3. Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, Jordan Crandall (ed.), Under fire. On the Organization and Representation of Violence, www.wdw.nl.

4. Article in the arts section of NRC Handelsblad, 16 October 2004.

5. Michael Kimmelman, ‘Museums: Abu Ghraib Returns - As Art?’, International Herald Tribune, 12 October 2004 (reprinted from The New York Times).

6. Slavoj Žižek, ‘Between Two Deaths. The Culture of Torture’, Infoshop News, 23 June 2004, www. infoshop.org.

7. Susan Sontag, ‘Regarding the Torture of Others’, The New York Times Magazine, 23 May 2004, www.southerncrossreview.org.

9.The Memory Hole, www.thememoryhole.org; www.thememoryhole.org; www.thememoryhole.org.

10. For photos see: journalism.berkeley.edu; wampum.wabanaki.net.

11. See, for example, reports from the NOS, BBC, and Camera / Iraq: www.nos. nl; news.bbc.co.uk; www.camerairaq.com.

12. See Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York 2003.

13. See note 7.

14. See note 6.

15. On the phenomenon of ‘re-enactment’ see, for example: livinghistory.leukestart.nl; www.n-a.co.uk; www.cwreenactors.com.

16. On re-enactment in art see, for example, Mediamatic, ‘Re-Enact’ report by Paul Groot, performance night organized by Mediamatic and CASCO, 12 December 2004, www.mediamatic.net. See also Metropolis M, no. 3, 2004.

17. From an article in de Volkskrant, 11 January 2005.

Jorinde Seijdel is an independent writer, editor and lecturer on subjects concerning art and media in our changing society and the public sphere. She is editor-in-chief of Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain (formerly known as Open. Cahier on Art & the Public Domain). In 2010 she published De waarde van de amateur [The Value of the Amateur] (Fonds BKVB, Amsterdam), about the rise of the amateur in digital culture and the notion of amateurism in contemporary art and culture. Currently, she is theory tutor at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and Head of the Studium Generale Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. With Open!, she is a partner of the Dutch Art Institute MA Art Praxis in Arnhem.